- Determinism

-

This article is about the general notion of determinism in philosophy. For other uses, see Determinism (disambiguation).

Certainty series Agnosticism

Belief

Certainty

Doubt

Determinism

Epistemology

Estimation

Fallibilism

Fatalism

Justification

Nihilism

Probability

Skepticism

Solipsism

Truth

UncertaintyDeterminism is the general philosophical thesis that states that for everything that happens there are conditions such that, given them, nothing else could happen. There are many versions of this thesis. Each of them rests upon various alleged connections, and interdependencies of things and events, asserting that these hold without exception. The wide variety of deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have sprung from diverse motives and considerations; some of which overlap considerably. All should be considered in the light of their historical significance, together with certain alternative theories that philosophers have proposed. At the same time, some forms of determinism may be empirically testable, and this page mentions some relevant ideas from physics and the philosophy of physics. The opposite of determinism is some kind of indeterminism (otherwise called "Nondeterminism").

Determinism is often taken to mean simply Causal determinism: an idea known in physics as cause-and-effect. It is the concept that events within a given paradigm are bound by causality in such a way that any state (of an object or event) is completely, or at least to some large degree, determined by prior states. This can be distinguished from other varieties of determinism mentioned below. Other debates often concern the scope of determined systems, with some maintaining that the entire universe (or multiverse) is a single determinate system and others identifying other more limited determinate systems[clarification needed]. Within numerous historical debates, many varieties and philosophical positions on the subject of determinism exist. This includes debates concerning human action and free will, where opinions might be sorted as compatibilistic and incompatibilistic.

Determinism should not be confused with self-determination of human actions by reasons, motives, and desires. Determinism rarely requires that perfect prediction be practically possible - only prediction in theory.

Contents

Varieties

Below are some of the more common viewpoints meant by, or confused with "Determinism".

Causal (or Nomological) determinism[1] and related Predeterminism propose that there is an unbroken chain of prior occurrences stretching back to the origin of the universe. The relation between events may not be specified, nor the origin of that universe. Causal determinists believe that there is nothing uncaused or self-caused. Quantum mechanics poses a serious challenge to this view (see 'Arguments' section below). Causal determinism is sometimes illustrated by the thought experiment of Laplace's demon. Historical determinism (a sort of path dependence) can also be synonymous with causal determinism.

Necessitarianism is very related to the causal determinism described above. It is a metaphysical principle that denies all mere possibility; there is exactly one way for the world to be. Leucippus claimed there were no uncaused events, and that everything occurs for a reason and by necessity.[2]

Fatalism is normally distinguished from "determinism".[3] Fatalism is the idea that everything is fated to happen, so that humans have no control over their future. Notice that fate has arbitrary power. Fate also need not follow any causal or otherwise deterministic laws.[1] Types of Fatalism include Theological determinism and the idea of predestination, where there is a God who determines all that humans will do. This may be accomplished either by knowing their actions in advance, via some form of omniscience[4] or by decreeing their actions in advance.[5]

Logical determinism or Determinateness is the notion that all propositions, whether about the past, present, or future, are either true or false. Note that one can support Causal Determinism without necessarily supporting Logical Determinism and vice versa (depending on one's views on the nature of time, but also randomness). The problem of free will is especially salient now with Logical Determinism: how can choices be free, given that propositions about the future already have a truth value in the present (i.e. it is already determined as either true or false)? This is referred to as the problem of future contingents.

Adequate determinism focuses on the fact that, even without a full understanding of microscopic physics, we can predict the distribution of 1000 coin tosses

Adequate determinism focuses on the fact that, even without a full understanding of microscopic physics, we can predict the distribution of 1000 coin tosses

Often synonymous with Logical Determinism are the ideas behind Spatio-temporal Determinism or Eternalism: the view of special relativity. J. J. C. Smart, a proponent of this view, uses the term "tenselessness" to describe the simultaneous existence of past, present, and future. In physics, the "block universe" of Hermann Minkowski and Albert Einstein assumes that time is a fourth dimension (like the three spatial dimensions). In other words, all the other parts of time are real, like the city blocks up and down a street, although the order in which they appear depends on the driver (see Rietdijk–Putnam argument).

Adequate determinism is the idea that quantum indeterminacy can be ignored for most macroscopic events. This is because of quantum decoherence. Random quantum events "average out" in the limit of large numbers of particles (where the laws of quantum mechanics asymptotically approach the laws of classical mechanics).[6] Stephen Hawking explains a similar idea: he says that the microscopic world of quantum mechanics is one of determined probabilities. That is, quantum effects rarely alter the predictions of classical mechanics, which are quite accurate (albeit still not perfectly certain) at larger scales.[7] Something as large as an animal cell, then, would be "adequately determined" (even in light of quantum indeterminacy).

Determined by nature or nurture

Although some of the above forms of determinism concern human behaviors and cognition, others frame themselves as an answer to the Nature or Nurture debate. They will suggest that one factor will entirely determine behavior. As scientific understanding has grown, however, the strongest versions of these theories have been widely rejected as a single cause fallacy.[8]

In other words, the modern deterministic theories attempt to explain how the interaction of both nature and nurture is entirely predictable. The concept of heritability has been helpful to make this distinction.

Biological determinism, sometimes called Genetic determinism, is the idea that each of our behaviors, beliefs, and desires are fixed by our genetic nature.

Behaviorism is the idea that all behavior can be traced to specific causes—either environmental or reflexive. This Nurture-focused determinism was developed by John B. Watson and B. F. Skinner.

Cultural determinism or social determinism is the nurture-focused theory that it is the culture in which we are raised that determines who we are.

Environmental determinism is also known as climatic or geographical determinism. It holds the view that the physical environment, rather than social conditions, determines culture. Supporters often also support Behavioral determinism. Key proponents of this notion have included Ellen Churchill Semple, Ellsworth Huntington, Thomas Griffith Taylor and possibly Jared Diamond, although his status as an environmental determinist is debated.[9]

Factor priority

Other 'deterministic' theories actually seek only to highlight the importance of a particular factor in predicting the future. These theories often use the factor as a sort of guide or constraint on the future. They need not suppose that complete knowledge of that one factor would allow us to make perfect predictions.

Psychological determinism can mean that humans must act according to reason, but it can also be synonymous with some sort of Psychological egoism. The latter is the view that humans will always act according to their perceived best interest.

Linguistic determinism claims that our language determines (at least limits) the things we can think and say and thus know. The Sapir–Whorf hypothesis argues that individuals experience the world based on the grammatical structures they habitually use.

Economic determinism is the theory which attributes primacy to the economic structure over politics in the development of human history. It is associated with the dialectical materialism of Karl Marx.

Technological determinism is a reductionist theory that presumes that a society's technology drives the development of its social structure and cultural values. Media determinism, a subset of technological determinism, is a philosophical and sociological position which posits the power of the media to impact society. Two leading media determinists are the Canadian scholars Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan.

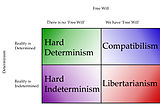

Free will and determinism

Philosophers have argued that either Determinism is true or Indeterminism is true, but also that 'Free will' either exists or it does not. This creates four possible positions. Compatibilism refers to the view that free will is, in some sense, compatible with Determinism. The three 'Incompatibilist' positions, on the other hand, deny this possibility. They instead suggest there is a dichotomy between determinism and free will (only one can be true).

To the Incompatibilists, one must choose either free will or Determinism, and maybe even reject both. The result is one of three positions:

- Metaphysical Libertarianism (free will, and no determinism) a position not to be confused with the more commonly cited Political Libertarianism

- Hard Determinism (Determinism, and no free will)

- Hard Indeterminism (No Determinism, and no free will either).

Thus, although many Determinists are Compatibilists, calling someone a 'Determinist' is often done to denote the 'Hard Determinist' position.

The Standard argument against free will, according to philosopher J. J. C. Smart focuses on the implications of Determinism for 'free will'.[10] He suggests that, if determinism is true, all our actions are predicted and we are not free; if determinism is false, our actions are random and still we do not seem free.

In his book, The Moral Landscape, author and neuroscientist Sam Harris mentions some ways that determinism and modern scientific understanding might challenge the idea of a contra-causal free will. He offers one thought experiment where a mad scientist represents determinism. In Harris' example, the mad scientist uses a machine to control all the desires, and thus all the behaviour, of a particular human. Harris believes that it is no longer as tempting, in this case, to say the victim has "free will". Harris says nothing changes if the machine controls desires at random - the victim still seems to lack free will. Harris then argues that we are also the victims of such unpredictable desires (but due to the unconscious machinations of our brain, rather than those of a mad scientist). Based on this introspection, he writes "This discloses the real mystery of free will: if our experience is compatible with its utter abscence, how can we say that we see any evidence for it in the first place?"[11] adding that "Whether they are predictable or not, we do not cause our causes."[12] That is, he believes there is compelling evidence of absence of free will.

Research has found that reducing a person's belief in free will risks making them less helpful and more aggressive;[13] this could occur because the individual's sense of Self-efficacy suffers.

Determinism and mind

Some determinists argue that materialism does not present a complete understanding of the universe, because while it can describe determinate interactions among material things, it ignores the minds or souls of conscious beings.

A number of positions can be delineated:

- Immaterial souls are all that exist (Idealism).

- Immaterial souls exist and exert a non-deterministic causal influence on bodies. (Traditional free-will, interactionist dualism).[14][15]

- Immaterial souls exist, but are part of deterministic framework.

- Immaterial souls exist, but exert no causal influence, free or determined (epiphenomenalism, occasionalism)

- Immaterial souls do not exist — there is no mind-body dichotomy, and there is a Materialistic explanation for intuitions to the contrary.

Another topic of debate is the implication that Determinism has on morality. Hard determinism (a belief in determinism, and not free will) is particularly criticized for seeming to make traditional moral judgments impossible. Some philosophers, however, find this an acceptable conclusion.

Philosopher and incompatibilist Peter van Inwagen introduces this thesis as such:

Argument that Free Will is Required for Moral Judgments

- The moral judgment that you shouldn’t have done X implies that you should have done something else instead

- That you should have done something else instead implies that there was something else for you to do

- That there was something else for you to do implies that you could have done something else

- That you could have done something else implies that you have free will

- If you don’t have free will to have done other than X we cannot make the moral judgment that you shouldn’t have done X.[16]

History

Some of the main philosophers who have dealt with this issue are Marcus Aurelius, Omar Khayyám, Thomas Hobbes, Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Leibniz, David Hume, Baron d'Holbach (Paul Heinrich Dietrich), Pierre-Simon Laplace, Arthur Schopenhauer, William James, Friedrich Nietzsche, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, and, more recently, John Searle, Ted Honderich, and Daniel Dennett.

Mecca Chiesa notes that the probabilistic or selectionistic determinism of B.F. Skinner comprised a wholly separate conception of determinism that was not mechanistic at all. Mechanistic determinism assumes that every event has an unbroken chain of prior occurrences, but a selectionistic or probabilistic model does not.[17][18]

Eastern tradition

The idea that the entire universe is a deterministic system has been articulated in both Eastern and non-Eastern religion, philosophy, and literature.

In I Ching and Philosophical Taoism, the ebb and flow of favorable and unfavorable conditions suggests the path of least resistance is effortless (see wu wei).

In the philosophical schools of India, the concept of precise and continual effect of laws of Karma on the existence of all sentient beings is analogous to western deterministic concept. Karma is the concept of "action" or "deed" in Indian religions. It is understood as that which causes the entire cycle of cause and effect (i.e., the cycle called saṃsāra) originating in ancient India and treated in Hindu, Jain, Sikh and Buddhist philosophies. Karma is considered predetermined and deterministic in the universe, with the exception of a human, who through free will can influence the future. See Karma in Hinduism.[citation needed]

Western tradition

The notion of determinism was introduced into the West through the adoption of the Abrahamic religions. The Christian concept of predestination led to the first Western debates over determinism, an issue that is known in theology as the paradox of free will. The Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides said of the determinstic implications of an omniscient god:[19] "Does God know or does He not know that a certain individual will be good or bad? If thou sayest 'He knows', then it necessarily follows that [that] man is compelled to act as God knew beforehand he would act, otherwise God's knowledge would be imperfect.…"[20]

Determinism in the West is often associated with Newtonian physics, which depicts the physical matter of the universe as operating according to a set of fixed, knowable laws. The "billiard ball" hypothesis, a product of Newtonian physics, argues that once the initial conditions of the universe have been established, the rest of the history of the universe follows inevitably. If it were actually possible to have complete knowledge of physical matter and all of the laws governing that matter at any one time, then it would be theoretically possible to compute the time and place of every event that will ever occur (Laplace's demon). In this sense, the basic particles of the universe operate in the same fashion as the rolling balls on a billiard table, moving and striking each other in predictable ways to produce predictable results.

Whether or not it is all-encompassing in so doing, Newtonian mechanics deals only with caused events, e.g.: If an object begins in a known position and is hit dead on by an object with some known velocity, then it will be pushed straight toward another predictable point. If it goes somewhere else, the Newtonians argue, one must question one's measurements of the original position of the object, the exact direction of the striking object, gravitational or other fields that were inadvertently ignored, etc. Then, they maintain, repeated experiments and improvements in accuracy will always bring one's observations closer to the theoretically predicted results. When dealing with situations on an ordinary human scale, Newtonian physics has been so enormously successful that it has no competition. But it fails spectacularly as velocities become some substantial fraction of the speed of light and when interactions at the atomic scale are studied. Before the discovery of quantum effects and other challenges to Newtonian physics, "uncertainty" was always a term that applied to the accuracy of human knowledge about causes and effects, and not to the causes and effects themselves.

Newtonian mechanics as well as any following physical theories are results of observations and experiments, and so they describe "how it all works" within a tolerance. However, old western scientists believed if there are any logical connections found between an observed cause and effect, there must be also some absolute natural laws behind. Belief in perfect natural laws driving everything, instead of just describing what we should expect, led to searching for a set of universal simple laws that rule the world. This movement significantly encouraged deterministic views in western philosophy.[21]

Modern perspectives

Cause and effect

Since the early twentieth century when astronomer Edwin Hubble first hypothesized that redshift shows the universe is expanding, prevailing scientific opinion has been that the current state of the universe is the result of a process described by the Big Bang. Many theists and deists claim that it therefore has a finite age, pointing out that something cannot come from nothing (the definition of nothing, however, is problematic at the most arcane level of physics). The big bang does not describe from where the compressed universe came; instead it leaves the question open. Different astrophysicists hold different views about precisely how the universe originated (Cosmogony). The philosophical argument here would be that the big bang triggered every single action, and possibly mental thought, through the system of cause and effect.

Generative processes

Although it was once thought by scientists that any indeterminism in quantum mechanics occurred at too small a scale to influence biological or neurological systems, there is evidence that nervous systems are indeterministic.[citation needed] It is unclear what implications this has for free will given various possible reactions to the standard problem in the first place.[22] Certainly not all biologists grant determinism: Christof Koch argues against it, and in favour of libertarian free will, by making arguments based on Generative processes (emergence).[23] Other proponents of emergentist or generative philosophy, cognitive sciences and evolutionary psychology, argue that determinism is true.[24] [25][26][27] They suggest instead that an illusion of free will is experienced due to the generation of infinite behaviour from the interaction of finite-deterministic set of rules and parameters. Thus the unpredictability of the emerging behaviour from deterministic processes leads to a perception of free will, even though free will as an ontological entity does not exist.[24][25][26][27] Certain experiments looking at the Neuroscience of free will can be said to support this possibility.

In Conway's Game of Life, the interaction of just 4 simple rules creates patterns that seem somehow "alive".

In Conway's Game of Life, the interaction of just 4 simple rules creates patterns that seem somehow "alive".

As an illustration, the strategy board-games chess and Go have rigorous rules in which no information (such as cards' face-values) is hidden from either player and no random events (such as dice-rolling) happen within the game. Yet, chess and especially Go with its extremely simple deterministic rules, can still have an extremely large number of unpredictable moves. By this analogy, it is suggested, the experience of free will emerges from the interaction of finite rules and deterministic parameters that generate nearly infinite and practically unpredictable behaviour. In theory, if all these events were accounted for, and there were a known way to evaluate these events, the seemingly unpredictable behaviour would become predictable.[24][25][26][27] Another hands-on example of generative processes is John Horton Conway's playable Game of Life.[28] Nassim Taleb is wary of such models, and coined the term "Ludic fallacy".

Mathematical models

Many mathematical models of physical systems are deterministic. This is true of most models involving differential equations (notably, those measuring rate of change over time). Mathematical models that are not deterministic because they involve randomness are called stochastic. Because of sensitive dependence on initial conditions, some deterministic models may appear to behave non-deterministically; in such cases, a deterministic interpretation of the model may not be useful due to numerical instability and a finite amount of precision in measurement. Such considerations can motivate the consideration of a stochastic model even though the underlying system is governed by deterministic equations.[29][30][31]

Quantum mechanics and classical physics

Day to day physics

Since the beginning of the 20th century, quantum mechanics - the physics of the extremely small - has revealed previously concealed aspects of events. Before that, Newtonian physics - the physics of every day life - dominated. Taken in isolation (rather than as an approximation to quantum mechanics), Newtonian physics depicts a universe in which objects move in perfectly determined ways. At the scale where humans exist and interact with the universe, Newtonian mechanics remain useful, and make relatively accurate predictions (e.g. calculating the trajectory of a bullet). In theory, absolute knowledge of the forces accelerating a bullet could produce an absolutely accurate prediction of its path. Modern quantum mechanics, however, casts reasonable doubt on this main thesis of determinism.

Relevant is the fact that certainty is never absolute in practice (and not just because of David Hume's problem of induction). The equations of Newtonian mechanics can exhibit sensitive dependence on initial conditions. This is an example of the Butterfly effect, which is one of the subjects of chaos theory. The idea is that something even as small as a butterfly could cause a chain reaction leading to a hurricane years later. Consequently, even a very small error in knowledge of initial conditions can result in arbitrarily large deviations from predicted behavior. Chaos theory thus explains why it may be practically impossible to predict real life, whether determinism is true or false. On the other hand, the issue may not be so much about human abilities to predict or attain certainty as much as it is the nature of reality itself. For that, a closer, scientific look at nature is necessary.

The quantum world

The quantum physics used at atomic scales works differently in many ways from Newtonian physics. Indeed, some findings are unintuitive and difficult to believe. Physicist Aaron D. O'Connell explains that understanding our universe, at such small scales as atoms, requires a different logic than day to day life. O'Connell does not deny that it is all interconnected: the scale of human existence ultimately does emerge from the quantum scale. O'Connell argues that we must simply use different models and constructs when dealing with the quantum world.[32] As a result, these branches of physics are sometimes misrepresented or misunderstood, making some claims seem more scientific than they are (e.g. The Secret (book)[33] or What The Bleep Do We Know!?[34]). Quantum mechanics remain, however, the product of careful application of the scientific method, logic and empiricism. For instance, Werner Heisenberg's carefully formulated Uncertainty principle explains why the paths of objects can only be predicted in a probabilistic way (the reasoning is nuanced, involving, among other things, the observer effect).

This is where statistical mechanics come into play, and where physicists begin to require rather unintuitive mental models: A particle's path simply cannot be exactly specified in its full quantum description. "Path" is a classical, practical attribute in our every day life, but one which quantum particles do not meaningfully possess. The probabilities discovered in quantum mechanics do nevertheless arise from measurement (of the perceived path of the particle). As Stephen Hawking explains, the result is not traditional determinism, but rather determined probabilities.[35] In some cases, a quantum particle may indeed trace an exact path, and the probability of finding the particles in that path is one.[clarification needed] In fact, as far as prediction goes, the quantum development is at least as predictable as the classical motion, but the key is that it describes wave functions that cannot be easily expressed in ordinary language. As far as the thesis of determinism is concerned, these probabilities, at least, are quite determined. These findings from quantum mechanics have found many applications, and allow us to build transistors and lasers. Put another way: personal computers, Blu-ray players and the internet all work because humankind discovered the determined probabilities of the quantum world.[33] None of that should be taken to imply that other aspects of quantum mechanics are not still up for debate.

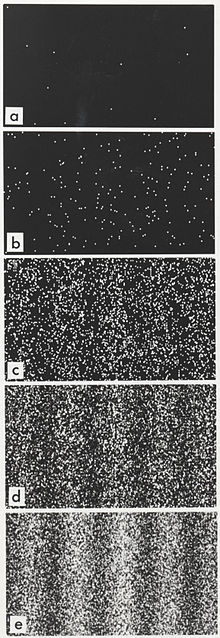

On the topic of predictable probabilities, the double-slit experiments are a popular example. Photons are fired one-by-one through a double-slit apparatus at a distant screen. Curiously, they do not arrive at any single point, nor even the two points lined up with the slits (the way you might expect of bullets fired by a fixed gun at a distant target). Instead, the light arrives in varying concentrations at widely separated points, and the distribution of its collisions with the target can be calculated reliably. In that sense the behavior of light in this apparatus is deterministic, but there is no way to predict where in the resulting interference pattern any individual photon will make its contribution (although, there may be ways to use weak measurement to acquire more information without violating the Uncertainty principle).

Some (including Albert Einstein) argue that our inability to predict any more than probabilities is simply due to ignorance.[36] The idea is that, beyond the conditions and laws we can observe or deduce, there are also hidden factors or "hidden variables" that determine absolutely in which order photons reach the detector screen. They argue that the course of the universe is absolutely determined, but that humans are screened from knowledge of the determinative factors. So, they say, it only appears that things proceed in a merely probabilistically determinative way. In actuality, they proceed in an absolutely deterministic way. These matters continue to be subject to some dispute. A critical finding was that quantum mechanics can make statistical predictions which would be violated if local hidden variables really existed. There have been a number of experiments to verify such predictions, and so far they do not appear to be violated. This would suggest there are no hidden variables, although many physicists believe better experiments are needed to conclusively settle the issue (see also Bell test experiments). Furthermore, it is possible to augment quantum mechanics with non-local hidden variables to achieve a deterministic theory that is in agreement with experiment. An example is the Bohm interpretation of quantum mechanics. This debate is relevant because it easy to imagine specific situations in which the arrival of an electron at a screen at a certain point and time would trigger one event, whereas its arrival at another point would trigger an entirely different event (e.g. see Schrödinger's cat - a thought experiment used as part of a deeper debate).

Thus, the world of quantum physics casts reasonable doubt on the traditional determinism that is so intuitive in classical, Newtonian physics. At the small scales, our reality does not seem to be absolutely determined. Yet this was precisely the subject of the famous Bohr–Einstein debates between Einstein and Niels Bohr. There is still no consensus. In the meantime, humans continue to benefit from the fact that reality obeys determined probabilities at the quantum scale. Such adequate determinism (see Varieties, above) is the reason that Stephen Hawking calls Libertarian free will "just an illusion".[35] Compatibilistic free will (which is deterministic) may be the only kind of "free will" that can exist. However, Daniel Dennett, in his book Elbow Room, says that this means we have the only kind of free will "worth wanting". For even more discussion, see Free will.

Other matters of quantum determinism

All uranium found on earth is thought to have been synthesized during a supernova explosion that occurred roughly 5 billion years ago. Even before the laws of quantum mechanics were developed to their present level, the radioactivity of such elements has posed a challenge to determinism due to its unpredictability. One gram of uranium-238, a commonly occurring radioactive substance, contains some 2.5 x 1021 atoms. Each of these atoms are identical and indistinguishable according to all tests known to modern science. Yet about 12600 times a second, one of the atoms in that gram will decay, giving off an alpha particle. The challenge for determinism is to explain why and when decay occurs, since it does not seem to depend on external stimulus. Indeed, no extant theory of physics makes testable predictions of exactly when any given atom will decay. At best scientists can discover determined probabilities in the form of the element's half life.

The time dependent Schrödinger equation gives the first time derivative of the quantum state. That is, it explicitly and uniquely predicts the development of the wave function with time.

So if the wave function itself is reality (rather than probability of classical coordinates), quantum mechanics can be said to be deterministic. Since we have no practical way of knowing the exact magnitudes, and especially the phases, in a full quantum mechanical description of the causes of an observable event, this turns out to be philosophically similar to the "hidden variable" doctrine[citation needed].

According to some,[citation needed] quantum mechanics is more strongly ordered than Classical Mechanics, because while Classical Mechanics is chaotic (appears random, specifically due to minor details - perhaps at a smaller scale), quantum mechanics is not. For example, the classical problem of three bodies under a force such as gravity is not integrable, while the quantum mechanical three body problem is tractable and integrable, using the Faddeev Equations.[clarification needed] This does not mean that quantum mechanics describes the world as more deterministic, unless one already considers the wave function to be the true reality. Even so, this does not get rid of the probabilities, because we can't do anything without using classical descriptions, but it assigns the probabilities to the classical approximation, rather than to the quantum reality.

Asserting that quantum mechanics is deterministic by treating the wave function itself as reality implies a single wave function for the entire universe, starting at the origin of the universe. Such a "wave function of everything" would carry the probabilities of not just the world we know, but every other possible world that could have evolved. For example, large voids in the distributions of galaxies are believed by many cosmologists to have originated in quantum fluctuations during the big bang. (See cosmic inflation and primordial fluctuations.) If so, the "wave function of everything" would carry the possibility that the region where our Milky Way galaxy is located could have been a void and the Earth never existed at all. (See large-scale structure of the cosmos.)

The idea of a first cause

Intrinsic to the debate concerning determinism is the issue of what caused the universe. The idea is that something that is in some sense 'outside' of the chain of determinism, and our usual understanding of causality, may have started the universe. Deism, for instance, makes a Cosmological argument: it holds that the universe has been deterministic since creation, but ascribes the creation to a metaphysical God. God may have begun the process, the deist argues, but God has not influenced its progression. Scientists have also approached the idea of something in some sense "causing" the universe, by appealing to a multiverse or related idea of Membranes. It remains debatable whether the problem has really been solved.

To be clear, most conception of determinism seem to face a puzzle when it comes to causality. Causality might be understood to mean that all events have prior causes. This suggests that there is no event (or group of events) that causes itself. There now seems to be only two possibilities - a dilemma: there is either (a) an infinite chain of causes which never "started" per se, and (b) something started causality as we understand it, but does not itself need to be caused. In other words: Did the universe or some event prior to it always exist? Or, if something needed to start the universe, what started that something - and how can we really prevent an infinite regress of causes?"

One way of this dilemma calls into question the idea of causality. It proposes making one exception: a creation event. A creation event is presumably not itself a "cause" in the sense of the word as used in the formulation of the original problem. These ideas were mentioned above, and attempt to terminate the regress just discussed. The idea of deism, for instance, is that some agency (or God) created space, time, and the entities found in the universe by means of some process that is analogous to causation (but again, is not causation as we know it).

Another possibility is that the "last event" loops back to the "first event" causing an infinite loop. If you were to call the Big Bang the first event, you would see the end of the Universe as the "last event". In theory, the end of the Universe would be the cause of the beginning of the Universe. You would be left with an infinite loop of time with no real beginning or end. This theory eliminates the need for a first cause, but does not explain why there should be a loop in time.

Immanuel Kant carried forth this idea of Leibniz in his idea of transcendental relations, and as a result, this had profound effects on later philosophical attempts to sort these issues out. His most influential immediate successor, a strong critic whose ideas were yet strongly influenced by Kant, was Edmund Husserl, the developer of the school of philosophy called phenomenology. But the central concern of that school was to elucidate not physics but the grounding of information that physicists and others regard as empirical. In an indirect way, this train of investigation appears to have contributed much to the philosophy of science called logical positivism and particularly to the thought of members of the Vienna Circle, all of which have had much to say, at least indirectly, about ideas of determinism.

See also

- Amor fati

- Block time

- Calvinism

- Chaos theory

- Digital physics

- Environmental determinism

- Fatalism

- Fractal

- False necessity

- Game theory

- Genetic determinism

- Ilya Prigogine

Notes

- ^ a b http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/incompatibilism-arguments/

- ^ Leucippus, Fragment 569 - from Fr. 2 Actius I, 25, 4

- ^ SEP, Causal Determinism

- ^ Fischer, John Martin (1989) God, Foreknowledge and Freedom. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 1-55786-857-3

- ^ Watt, Montgomery (1948) Free-Will and Predestination in Early Islam. London:Luzac & Co.

- ^ The Information Philosopher website, "Adequate Determinism", from the site: "We are happy to agree with scientists and philosophers who feel that quantum effects are for the most part negligible in the macroscopic world. We particularly agree that they are negligible when considering the causally determined will and the causally determined actions set in motion by decisions of that will."

- ^ Grand Design (2010), page 32: "the molecular basis of biology shows that biological processes are governed by the laws of physics and chemistry and therefore are as determined as the orbits of the planets.", and page 72: "Quantum physics might seem to undermine the idea that nature is governed by laws, but that is not the case. Instead it leads us to accept a new form of determinism: Given the state of a system at some time, the laws of nature determine the probabilities of various futures and pasts rather than determining the future and past with certainty." (emphasis in original, discussing a Many worlds interpretation)

- ^ de Melo-Martín I (2005). "Firing up the nature/nurture controversy: bioethics and genetic determinism". J Med Ethics 31 (9): 526–30. doi:10.1136/jme.2004.008417. PMC 1734214. PMID 16131554. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1734214.

- ^ Andrew, Sluyter. "Neo-Environmental Determinism, Intellectual Damage Control, and Nature/Society Science". Antipode 4 (35).

- ^ J. J. C. Smart, "Free-Will, Praise and Blame,"Mind, July 1961, p.293-4.

- ^ Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape (2010), pg.216, note102

- ^ Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape (2010), pg.217, note109

- ^ Baumeister RF, Masicampo EJ, Dewall CN. (2009). Prosocial benefits of feeling free: disbelief in free will increases aggression and reduces helpfulness. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 35(2):260-8. PMID 19141628 doi:10.1177/0146167208327217

- ^ By 'soul' in the context of (1) is meant an autonomous immaterial agent that has the power to control the body but not to be controlled by the body (this theory of determinism thus conceives of conscious agents in dualistic terms). Therefore the soul stands to the activities of the individual agent's body as does the creator of the universe to the universe. The creator of the universe put in motion a deterministic system of material entities that would, if left to themselves, carry out the chain of events determined by ordinary causation. But the creator also provided for souls that could exert a causal force analogous to the primordial causal force and alter outcomes in the physical universe via the acts of their bodies. Thus, it emerges that no events in the physical universe are uncaused. Some are caused entirely by the original creative act and the way it plays itself out through time, and some are caused by the acts of created souls. But those created souls were not created by means of physical processes involving ordinary causation. They are another order of being entirely, gifted with the power to modify the original creation. However, determinism is not necessarily limited to matter; it can encompass energy as well. The question of how these immaterial entities can act upon material entities is deeply involved in what is generally known as the mind-body problem. It is a significant problem which philosophers have not reached agreement about

- ^ Free Will (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- ^ van Inwagen, Peter (2009). The Powers of Rational Beings: Freedom of the Will. Oxford.

- ^ Chiesa, Mecca (2004) Radical Behaviorism: The Philosophy & The Science.

- ^ Ringen, J. D. (1993). Adaptation, teleology, and selection by consequences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 60,3–15. [1]

- ^ Though Moses Maimonides was not arguing against the existence of God, but rather for the incompatibility between the full exercise by God of his omniscience and genuine human free will, his argument is considered by some as affected by Modal Fallacy. See, in particular, the article by Prof. Norman Swartz for Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Foreknowledge and Free Will and specifically Section 6: The Modal Fallacy

- ^ The Eight Chapters of Maimonides on Ethics (Semonah Perakhim), edited, annotated, and translated with an Introduction by Joseph I. Gorfinkle, pp. 99–100. (New York: AMS Press), 1966.

- ^ Swartz, Norman (2003) The Concept of Physical Law / Chapter 10: Free Will and Determinism ( http://www.sfu.ca/philosophy/physical-law/)

- ^ Lewis, E.R.; MacGregor, R.J. (2006). "On Indeterminism, Chaos, and Small Number Particle Systems in the Brain". Journal of Integrative Neuroscience 5 (2): 223–247. doi:10.1142/S0219635206001112. http://www.eecs.berkeley.edu/~lewis/LewisMacGregor.pdf.

- ^ Koch, Christof (September 2009). "Free Will, Physics, Biology and the Brain". In Murphy, Nancy; Ellis, George; O'Connor, Timothy. Downward Causation and the Neurobiology of Free Will. New York, USA: Springer. ISBN 978-3642032042.

- ^ a b c Kenrick, D. T., Li, N. P., & Butner, J. (2003) "Dynamical evolutionary psychology: Individual decision rules and emergent social norms," Psychological Review 110: 3–28.

- ^ a b c Nowak A., Vallacher R.R., Tesser A., Borkowski W., (2000) "Society of Self: The emergence of collective properties in self-structure," Psychological Review 107.

- ^ a b c Epstein J.M. and Axtell R. (1996) Growing Artificial Societies - Social Science from the Bottom. Cambridge MA, MIT Press.

- ^ a b c Epstein J.M. (1999) Agent Based Models and Generative Social Science. Complexity, IV (5)

- ^ John Conway's Game of Life

- ^ Werndl, Charlotte (2009). Are Deterministic Descriptions and Indeterministic Descriptions Observationally Equivalent?. Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 40, 232-242.

- ^ Werndl, Charlotte (2009). Deterministic Versus Indeterministic Descriptions: Not That Different After All?. In: A. Hieke and H. Leitgeb (eds), Reduction, Abstraction, Analysis, Proceedings of the 31st International Ludwig Wittgenstein-Symposium. Ontos, 63-78.

- ^ J. Glimm, D. Sharp, Stochastic Differential Equations: Selected Applications in Continuum Physics, in: R.A. Carmona, B. Rozovskii (ed.) Stochastic Partial Differential Equations: Six Perspectives, American Mathematical Society (October 1998) (ISBN 0-8218-0806-0).

- ^ "Struggling with quantum logic: Q&A with Aaron O'Connell

- ^ a b Scientific American, "What is Quantum Mechanics Good For?"

- ^ Mone, Gregory (October 2004). "Cult Science Dressing Up Mysticism as Quantum Physics". Popular Science. http://www.popsci.com/scitech/article/2004-10/cult-science. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ^ a b Grand Design (2010), page 32: "the molecular basis of biology shows that biological processes are governed by the laws of physics and chemistry and therefore are as determined as the orbits of the planets...so it seems that we are no more than biological machines and that free will is just an illusion", and page 72: "Quantum physics might seem to undermine the idea that nature is governed by laws, but that is not the case. Instead it leads us to accept a new form of determinism: Given the state of a system at some time, the laws of nature determine the probabilities of various futures and pasts rather than determining the future and past with certainty." (discussing a Many worlds interpretation)

- ^ Albert Einstein insisted that, "I am convinced God does not play dice" in a private letter to Max Born, 4 December 1926, Albert Einstein Archives reel 8, item 180

References and bibliography

- Daniel Dennett (2003) Freedom Evolves. Viking Penguin.

- John Earman (2007) "Aspects of Determinism in Modern Physics" in Butterfield, J., and Earman, J., eds., Philosophy of Physics, Part B. North Holland: 1369-1434.

- George Ellis (2005) "Physics and the Real World," Physics Today.

- Epstein J.M. (1999) "Agent Based Models and Generative Social Science," Complexity IV (5).

- -------- and Axtell R. (1996) Growing Artificial Societies — Social Science from the Bottom. MIT Press.

- Kenrick, D. T., Li, N. P., & Butner, J. (2003) "Dynamical evolutionary psychology: Individual decision rules and emergent social norms," Psychological Review 110: 3–28.

- Albert Messiah, Quantum Mechanics, English translation by G. M. Temmer of Mécanique Quantique, 1966, John Wiley and Sons, vol. I, chapter IV, section III.

- Nowak A., Vallacher R.R., Tesser A., Borkowski W., (2000) "Society of Self: The emergence of collective properties in self-structure," Psychological Review 107.

- Schimbera, Jürgen / Schimbera, Peter: Determination des Indeterminierten. Kritische Anmerkungen zur Determinismus- und Freiheitskontroverse. Verlag Dr. Kovac, Hamburg 20 November 2011, ISBN 978-3-8300-5099-5.

External links

- Hard determinism proved

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Causal Determinism

- Determinism in History from the Dictionary of the History of Ideas

- Philosopher Ted Honderich's Determinism web resource

- Determinism on Information Philosopher

- An Introduction to Free Will and Determinism by Paul Newall, aimed at beginners.

- The Society of Natural Science

- Determinism and Free Will in Judaism

- Snooker, Pool, and Determinism

Categories:- Determinism

- Philosophy of science

- Metaphysical theories

- Randomness

- Causality

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.