- Political philosophy

-

Part of the Politics series Politics - List of political topics

- Politics by country

- Politics by subdivision

- Political economy

- Political history

- Political history of the world

- Political philosophy

- Political science

- Political system

- Legislature

- Executive

- Judiciary

- Electoral branch

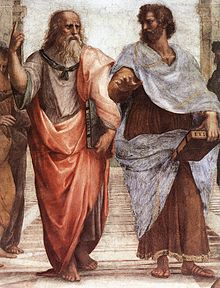

Subseries Politics portal  Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), from a detail of The School of Athens, a fresco by Raphael. Plato's Republic and Aristotle's Politics secured the two Greek philosophers as two of the most influential political philosophers.

Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), from a detail of The School of Athens, a fresco by Raphael. Plato's Republic and Aristotle's Politics secured the two Greek philosophers as two of the most influential political philosophers.

Political philosophy is the study of such topics as liberty, justice, property, rights, law, and the enforcement of a legal code by authority: what they are, why (or even if) they are needed, what, if anything, makes a government legitimate, what rights and freedoms it should protect and why, what form it should take and why, what the law is, and what duties citizens owe to a legitimate government, if any, and when it may be legitimately overthrown—if ever. In a vernacular sense, the term "political philosophy" often refers to a general view, or specific ethic, political belief or attitude, about politics that does not necessarily belong to the technical discipline of philosophy.[1]

Political philosophy can also be understood by analysing it through the perspectives of metaphysics, epistemology and axiology. It provides insight into, among other things, the various aspects of the origin of the state, its institutions and laws.

Contents

History of political philosophy

Further information: History of political thoughtAncient

Ancient China

Chinese political philosophy dates back to the Spring and Autumn Period, specifically with Confucius in the 6th century BC. Chinese political philosophy developed as a response to the social and political breakdown of the country characteristic of the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period. The major philosophies during the period, Confucianism, Legalism, Mohism, Agrarianism and Taoism, each had a political aspect to their philosophical schools. Philosophers such as Confucius, Mencius, and Mozi, focused on political unity and political stability as the basis of their political philosophies. Confucianism advocated a hierarchical, meritocratic government based on empathy, loyalty, and interpersonal relationships. Legalism advocated a highly authoritarian government based on draconian punishments and laws. Mohism advocated a communal, decentralized government centered on frugality and ascetism. The Agrarians advocated a peasant utopian communalism and egalitarianism.[2] Taoism advocated a proto-anarchism. Legalism was the dominant political philosophy of the Qin Dynasty, but was replaced by Confucianism in the Han Dynasty. Prior to China's adoption of communism, Confucianism remained the dominant political philosophy of China up to the 20th century.[3]

Ancient Greece

Western political philosophy originates in the philosophy of ancient Greece, where political philosophy begins with Plato's The Republic in the 4th century BC.[4] Ancient Greece was dominated by city-states, which experimented with various forms of political organization, grouped by Plato into four categories: timocracy, tyranny, democracy and oligarchy. One of the first, extremely important classical works of political philosophy is Plato's The Republic,[4] which was followed by Aristotle's Politics and Nichomachean Ethics.[5] Roman political philosophy was influenced by the Stoics, including the Roman statesman Cicero.[6]

Ancient India

Political philosophy originates in Ancient India with the Laws of Manu[7] and Chanakya. Chanakya, in his Arthashastra, developed a viewpoint which recalls both the Legalists and Niccolò Machiavelli.

Medieval Christianity

Saint Augustine

The early Christian philosophy of Augustine of Hippo was by and large a rewrite[citation needed] of Plato in a Christian context. The main change that Christian thought brought was to moderate the Stoicism and theory of justice of the Roman world, and emphasize the role of the state in applying mercy as a moral example. Augustine also preached that one was not a member of his or her city, but was either a citizen of the City of God (Civitas Dei) or the City of Man (Civitas Terrena). Augustine's City of God is an influential work of this period that refuted the thesis, after the First Sack of Rome, that the Christian view could be realized on Earth at all - a view many Christian Romans held.[8]

Saint Thomas Aquinas

In political philosophy, Aquinas is most meticulous when dealing with varieties of law. According to Aquinas, there are four different kinds of laws:

1) God's cosmic law

2) God's scriptural law

3) Natural law or rules of conduct universally applicable within reason

4) Human law or specific rules applicable to specific circumstances.

Medieval Islam

Mutazilite vs Asharite

The rise of Islam, based on both the Qur'an and Muhammad strongly altered the power balances and perceptions of origin of power in the Mediterranean region. Early Islamic philosophy emphasized an inexorable link between science and religion, and the process of ijtihad to find truth - in effect all philosophy was "political" as it had real implications for governance. This view was challenged by the "rationalist" Mutazilite philosophers, who held a more Hellenic view, reason above revelation, and as such are known to modern scholars as the first speculative theologians of Islam; they were supported by a secular aristocracy who sought freedom of action independent of the Caliphate. By the late ancient period, however, the "traditionalist" Asharite view of Islam had in general triumphed. According to the Asharites, reason must be subordinate to the Quran and the Sunna.[9]

Islamic political philosophy, was, indeed, rooted in the very sources of Islam, i.e. the Qur'an and the Sunnah, the words and practices of Muhammad. However, in the Western thought, it is generally supposed that it was a specific area peculiar merely to the great philosophers of Islam: al-Kindi (Alkindus), al-Farabi (Abunaser), İbn Sina (Avicenna), Ibn Bajjah (Avempace), Ibn Rushd (Averroes), and Ibn Khaldun. The political conceptions of Islam such as kudrah (power), sultan, ummah, cemaa (obligation)-and even the "core" terms of the Qur'an, i.e. ibadah, din (religion), rab (master) and ilah- is taken as the basis of an analysis. Hence, not only the ideas of the Muslim political philosophers but also many other jurists and ulama posed political ideas and theories. For example, the ideas of the Khawarij in the very early years of Islamic history on Khilafa and Ummah, or that of Shia Islam on the concept of Imamah are considered proofs of political thought. The clashes between the Ehl-i Sunna and Shia in the 7th and 8th centuries had a genuine political character.

Ibn Khaldun

The 14th century Arab scholar Ibn Khaldun is considered one of the greatest political theorists. The British philosopher-anthropologist Ernest Gellner considered Ibn Khaldun's definition of government, "an institution which prevents injustice other than such as it commits itself", the best in the history of political theory. For Ibn Khaldun, government should be restrained to a minimum for as a necessary evil, it is the constraint of men by other men.[10]

Islamic political philosophy did not cease in the classical period. Despite the fluctuations in its original character during the medieval period, it has lasted even in the modern era. Especially with the emergence of Islamic radicalism as a political movement, political thought has revived in the Muslim world. The political ideas of Abduh, Afgani, Kutub, Mawdudi, Shariati and Khomeini has caught on an ethusiasm especially in Muslim youth in the 20th century.

Medieval Europe

Medieval political philosophy in Europe was heavily influenced by Christian thinking. It had much in common with the Mutazalite Islamic thinking in that the Roman Catholics though subordinating philosophy to theology did not subject reason to revelation but in the case of contradictions, subordinated reason to faith as the Asharite of Islam. The Scholastics by combining the philosophy of Aristotle with the Christianity of St. Augustine emphasized the potential harmony inherent in reason and revelation.[11] Perhaps the most influential political philosopher of medieval Europe was St. Thomas Aquinas who helped reintroduce Aristotle's works, which had only been preserved by the Muslims, along with the commentaries of Averroes. Aquinas's use of them set the agenda, for scholastic political philosophy dominated European thought for centuries even unto the Renaissance.[12]

Medieval political philosophers, such as Aquinas in Summa Theologica, developed the idea that a king who is a tyrant is no king at all and could be overthrown.

Magna Carta, cornerstone of Anglo-American political liberty, explicitly proposes the right to revolt against the ruler for justice sake. Other documents similar to Magna Carta are found in other European countries such as Spain and Hungary.[13]

European Renaissance

During the Renaissance secular political philosophy began to emerge after about a century of theological political thought in Europe. While the Middle Ages did see secular politics in practice under the rule of the Holy Roman Empire, the academic field was wholly scholastic and therefore Christian in nature.

Niccolò Machiavelli

One of the most influential works during this burgeoning period was Niccolò Machiavelli's The Prince, written between 1511–12 and published in 1532, after Machiavelli's death. That work, as well as The Discourses, a rigorous analysis of the classical period, did much to influence modern political thought in the West. A minority (including Jean-Jacques Rousseau) could interpret The Prince as a satire meant to be given to the Medici after their recapture of Florence and their subsequent expulsion of Machiavelli from Florence.[14] Though the work was written for the di Medici family in order to perhaps influence them to free him from exile, Machiavelli supported the Republic of Florence rather than the oligarchy of the di Medici family. At any rate, Machiavelli presents a pragmatic and somewhat consequentialist view of politics, whereby good and evil are mere means used to bring about an end, i.e. the secure and powerful state. Thomas Hobbes, well known for his theory of the social contract, goes on to expand this view at the start of the 17th century during the English Renaissance. Although neither Machiavelli nor Hobbes believed in the divine right of kings, they both believed in the inherent selfishness of the individual. It was necessarily this belief that led them to adopt a strong central power as the only means of preventing the disintegration of the social order.[15]

John Locke

John Locke in particular exemplified this new age of political theory with his work Two Treatises of Government. In it Locke proposes a state of nature theory that directly complements his conception of how political development occurs and how it can be founded through contractual obligation. Locke stood to refute Sir Robert Filmer's paternally founded political theory in favor of a natural system based on nature in a particular given system. The theory of the divine right of kings became a passing fancy, exposed to the type of ridicule with which John Locke treated it. Unlike Machiavelli and Hobbes but like Aquinas, Locke would accept Aristotle's dictum that man seeks to be happy in a state of social harmony as a social animal. Unlike Aquinas's preponderant view on the salvation of the soul from original sin, Locke believes man's mind comes into this world as tabula rasa. For Locke, knowledge is neither innate, revealed nor based on authority but subject to uncertainty tempered by reason, tolerance and moderation. According to Locke, an absolute ruler as proposed by Hobbes is unnecessary, for natural law is based on reason and seeking peace and survival for man.

European Age of Enlightenment

Eugène Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People (1830, Louvre), a painting created at a time where old and modern political philosophies came into violent conflict.

Eugène Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People (1830, Louvre), a painting created at a time where old and modern political philosophies came into violent conflict.

During the Enlightenment period, new theories about what the human was and is and about the definition of reality and the way it was perceived, along with the discovery of other societies in the Americas, and the changing needs of political societies (especially in the wake of the English Civil War, the American Revolution and the French Revolution) led to new questions and insights by such thinkers as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Montesquieu and John Locke.

These theorists were driven by two basic questions: one, by what right or need do people form states; and two, what the best form for a state could be. These fundamental questions involved a conceptual distinction between the concepts of "state" and "government." It was decided that "state" would refer to a set of enduring institutions through which power would be distributed and its use justified. The term "government" would refer to a specific group of people who occupied the institutions of the state, and create the laws and ordinances by which the people, themselves included, would be bound. This conceptual distinction continues to operate in political science, although some political scientists, philosophers, historians and cultural anthropologists have argued that most political action in any given society occurs outside of its state, and that there are societies that are not organized into states which nevertheless must be considered in political terms. As long as the concept of natural order was not introduced, the social sciences could not evolve independently of theistic thinking. Since the cultural revolution of the 17th century in England, which spread to France and the rest of Europe, society has been considered subject to natural laws akin to the physical world.[16]

Political and economic relations were drastically influenced by these theories as the concept of the guild was subordinated to the theory of free trade, and Roman Catholic dominance of theology was increasingly challenged by Protestant churches subordinate to each nation-state, which also (in a fashion the Roman Catholic Church often decried angrily) preached in the vulgar or native language of each region. However, the enlightenment was an outright attack on religion, particularly Christianity. The publication of Denis Diderot's and Jean d'Alembert's Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers marked the crowning intellectual achievement of the epoch. The most outspoken critic of the church in France was François Marie Arouet de Voltaire, a representative figure of the enlightenment. After Voltaire, religion would never be the same again in France.[17]

In the Ottoman Empire, these ideological reforms did not take place and these views did not integrate into common thought until much later. As well, there was no spread of this doctrine within the New World and the advanced civilizations of the Aztec, Maya, Inca, Mohican, Delaware, Huron and especially the Iroquois. The Iroquois philosophy in particular gave much to Christian thought of the time and in many cases actually inspired some of the institutions adopted in the United States: for example, Benjamin Franklin was a great admirer of some of the methods of the Iroquois Confederacy, and much of early American literature emphasized the political philosophy of the natives.[18]

Industrialization and the Modern Era

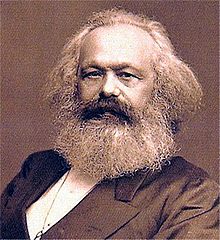

Karl Marx and his theory of Communism developed along with Friedrich Engels proved to be one of the most influential political ideologies of the 20th century through Leninism.

Karl Marx and his theory of Communism developed along with Friedrich Engels proved to be one of the most influential political ideologies of the 20th century through Leninism.

The industrial revolution produced a parallel revolution in political thought. Urbanization and capitalism greatly reshaped society. During this same period, the socialist movement began to form. In the mid-19th century, Marxism was developed, and socialism in general gained increasing popular support, mostly from the urban working class. Without breaking entirely from the past, Marx established the principles which would be used by the future revolutionaries of the 20th century namely Lenin, Mao Tse Tung, Ho Chi Minh and Fidel Castro. Although Hegel's philosophy of history is similar to Kant's, and Marx's theory of revolution towards the common good is partly based on Kant's view of history, Marx is said to have declared that on the whole, he was just trying to straighten out Hegel who was actually upside down. Unlike Marx who believed in historical materialism, Hegel believed in the Phenomenology of Spirit.[19] Be that as it may, by the late 19th century, socialism and trade unions were established members of the political landscape. In addition, the various branches of anarchism, with thinkers such as Bakunin, Proudhon or Kropotkin, and syndicalism also gained some prominence. In the Anglo-American world, anti-imperialism and pluralism began gaining currency at the turn of the century.

World War I was a watershed event in human history. The Russian Revolution of 1917 (and similar, albeit less successful, revolutions in many other European countries) brought communism - and in particular the political theory of Leninism, but also on a smaller level Luxemburgism (gradually) - on the world stage. At the same time, social democratic parties won elections and formed governments for the first time, often as a result of the introduction of universal suffrage.[20] However, a group of central European economists led by Austrians Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek identified the collectivist underpinnings to the various new socialist and fascist doctrines of government power as being different brands of political totalitarianism.[21][22]

Contemporary political philosophy

From the end of World War II until 1971, when John Rawls published a Theory of Justice, political philosophy declined in the Anglo-American academic world, as analytic philosophers expressed skepticism about the possibility that normative judgments had cognitive content, and political science turned toward statistical methods and behavioralism. In continental Europe, on the other hand, the postwar decades saw a huge blossoming of political philosophy, with Marxism dominating the field. This was the time of Sartre and Althusser, and the victories of Mao Zedong in China and Fidel Castro in Cuba, as well as the events of May 1968 led to increased interest in revolutionary ideology, especially by the New Left. A number of continental European émigrés to Britain and the United States—including Hannah Arendt, Karl Popper, Friedrich Hayek, Leo Strauss, Isaiah Berlin, Eric Voegelin and Judith Shklar—encouraged continued study in political philosophy in the Anglo-American world, but in the 1950s and 60s they and their students remained at odds with the analytic establishment.

Communism remained an important focus especially during the 1950s and 60s. Colonialism and racism were important issues that arose. In general, there was a marked trend towards a pragmatic approach to political issues, rather than a philosophical one. Much academic debate regarded one or both of two pragmatic topics: how (or whether) to apply utilitarianism to problems of political policy, or how (or whether) to apply economic models (such as rational choice theory) to political issues. The rise of feminism, LGBT social movements and the end of colonial rule and of the political exclusion of such minorities as African Americans and sexual minorities in the developed world has led to feminist, postcolonial, and multicultural thought becoming significant.

In Anglo-American academic political philosophy the publication of John Rawls's A Theory of Justice in 1971 is considered a milestone. Rawls used a thought experiment, the original position, in which representative parties choose principles of justice for the basic structure of society from behind a veil of ignorance. Rawls also offered a criticism of utilitarian approaches to questions of political justice. Robert Nozick's 1974 book Anarchy, State, and Utopia, which won a National Book Award, responded to Rawls from a libertarian perspective and gained academic respectability for libertarian viewpoints.[23]

Contemporaneously with the rise of analytic ethics in Anglo-American thought, in Europe several new lines of philosophy directed at critique of existing societies arose between the 1950s and 1980s. Most of these took elements of Marxist economic analysis, but combined them with a more cultural or ideological emphasis. Out of the Frankfurt School, thinkers like Herbert Marcuse, Theodor W. Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Jürgen Habermas combined Marxian and Freudian perspectives. Along somewhat different lines, a number of other continental thinkers—still largely influenced by Marxism—put new emphases on structuralism and on a "return to Hegel". Within the (post-) structuralist line (though mostly not taking that label) are thinkers such as Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, Claude Lefort, and Jean Baudrillard. The Situationists were more influenced by Hegel; Guy Debord, in particular, moved a Marxist analysis of commodity fetishism to the realm of consumption, and looked at the relation between consumerism and dominant ideology formation.

Another debate developed around the (distinct) criticisms of liberal political theory made by Michael Sandel and Charles Taylor. The liberal-communitarian debate is often considered valuable for generating a new set of philosophical problems, rather than a profound and illuminating clash of perspectives.

Charles Blattberg has offered an account which distinguishes between four different contemporary political philosophies: neutralism, postmodernism, pluralism, and patriotism.[24]

There is fruitful interaction between political philosophers and international relations theorists. The rise of globalization has created the need for an international normative framework, and political theory has moved to fill the gap.

Influential political philosophers

A larger list of political philosophers is intended to be closer to exhaustive. Listed below are a few of the most canonical or important thinkers, and especially philosophers whose central focus was in political philosophy and/or who are good representatives of a particular school of thought.

- Aristotle: Wrote his Politics as an extension of his Nicomachean Ethics. Notable for the theories that humans are social animals, and that the polis (Ancient Greek city state) existed to bring about the good life appropriate to such animals. His political theory is based upon an ethics of perfectionism (as is Marx's, on some readings).

- Thomas Aquinas: In synthesizing Christian theology and Peripatetic (aristotelian) teaching, Aquinas contends that God's gift of higher reason—manifest in human law by way of the divine virtues—gives way to the assembly of righteous government.

- Jeremy Bentham: The first thinker to analyze social justice in terms of maximization of aggregate individual benefits. Founded the philosophical/ethical school of thought known as utilitarianism.

- Isaiah Berlin: Developed the distinction between positive and negative liberty

- Edmund Burke: Irish member of the British parliament, Burke is credited with the creation of conservative thought. Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France is the most popular of his writings where he denounced the French revolution. Burke was one of the biggest supporters of the American Revolution.

- Confucius: The first thinker to relate ethics to the political order.

- William E. Connolly: Helped introduce postmodern philosophy into political theory, and promoted new theories of pluralism and agonistic democracy.

- John Dewey: Co-founder of pragmatism and analyzed the essential role of education in the maintenance of democratic government.

- Herman Dooyeweerd: Gave full philosophical development to the Dutch Anti Revolutionary Party's concept of sphere sovereignty, which implies that no one area of societal community (incl. the state) should seek totalitarian control, or any regulation of human activity outside its limited competence. He then widened his interests into general philosophy, making contributions on the nature of diversity, and the conditions for theoretical thought and on the links between religion and philosophy.

- Han Feizi: The major figure of the Chinese Fajia (Legalist) school, advocated government that adhered to laws and a strict method of administration.

- Michel Foucault: Critiqued the modern conception of power on the basis of the prison complex and other prohibitive institutions, such as those that designate sexuality, madness and knowledge as the roots of their infrastructure, a critique which then demonstrated that subjection is the power formation of subjects in any linguistic forum and that revolution cannot just be thought as the reversal of power between classes.

- Sigmund Freud: While he is known more for his work on the psychoanalysis of individuals, in his later years he also considered the implications of his theories on societies and the state of nature in a number of books, most notably Civilization and its Discontents. His thought was grossly influential for the theoriests of The Frankfurt School who fused his theory with Marxism to create Freudo-Marxism, and also the New Left of Herbert Marcuse.

- Antonio Gramsci: Instigated the concepts hegemony and social formation. Fused the ideas of Marx, Engels, Spinoza and others within the so-called dominant ideology thesis (the ruling ideas of society are the ideas of its rulers).

- Mister Theriault: teaches a mean P-Theory class.

- Thomas Hill Green: Modern liberal thinker and early supporter of positive freedom.

- Friedrich Hayek: He argued that central planning was inefficient because members of central bodies could not know enough to match the preferences of consumers and workers with existing conditions. Hayek further argued that central economic planning - a mainstay of socialism - would lead to a "total" state with dangerous power. He advocated free-market capitalism in which the main role of the state is to maintain the rule of law and let the spontaneous order develop. He also suggested that society was just made up of economic relations, which is the difference between neo-liberalism ideology's market system and laissez-faire economics.

- Martin Heidegger: Distilled his view of the three possible political "systems" of the future, after nihilism has pervaded the world: Americanism, Marxism, and Nazism. His influence is noted in his political thinkers such as Leo Strauss and Hannah Arrendt. He was an unrepentant Nazi.

- G. W. F. Hegel: Emphasized the "cunning" of history, arguing that it followed a rational trajectory, even while embodying seemingly irrational forces; influenced Marx, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Oakeshott.

- Thomas Hobbes: Generally considered to have first articulated how the concept of a social contract that justifies the actions of rulers (even where contrary to the individual desires of governed citizens), can be reconciled with a conception of sovereignty.

- David Hume: Hume criticized the social contract theory of John Locke and others as resting on a myth of some actual agreement. Hume was a realist in recognizing the role of force to forge the existence of states and that consent of the governed was merely hypothetical. He also introduced the concept of utility, later picked up on and developed by Jeremy Bentham.

- Thomas Jefferson: Politician and political theorist during the American Enlightenment. Expanded on the philosophy of Thomas Paine by instrumenting republicanism in the United States. Most famous for the United States Declaration of Independence.

- Immanuel Kant: Argued that participation in civil society is undertaken not for self-preservation, as per Thomas Hobbes, but as a moral duty. First modern thinker who fully analyzed structure and meaning of obligation. Argued that an international organization was needed to preserve world peace.

- John Locke: Like Hobbes, described a social contract theory based on citizens' fundamental rights in the state of nature. He departed from Hobbes in that, based on the assumption of a society in which moral values are independent of governmental authority and widely shared, he argued for a government with power limited to the protection of personal property. His arguments may have been deeply influential to the formation of the United States Constitution.

- Niccolò Machiavelli: First systematic analyses of: (1) how consent of a populace is negotiated between and among rulers rather than simply a naturalistic (or theological) given of the structure of society; (2) precursor to the concept of ideology in articulating the epistemological structure of commands and law.

- James Madison: American politician and protege of Jefferson considered to be “Father of the Constitution” and “Father of the Bill of Rights” of the United States. As a political theorist, he believed in separation of powers and proposed a comprehensive set of checks and balances that are necessary to protect the rights of an individual from the tyranny of the majority.

- Henry David Thoreau: influential American thinker on such diverse later political positions and topics such as pacifism, anarchism, environmentalism and civil disobedience who influenced later important political activists such as Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi and Leo Tolstoy.

- Herbert Marcuse: One of the principal thinkers within the Frankfurt School, and generally important in efforts to fuse the thought of Sigmund Freud and Karl Marx. Introduced the concept of repressive desublimation, in which social control can operate not only by direct control, but also by manipulation of desire. Analyzed the role of advertising and propaganda in societal consensus.

- Karl Marx: In large part, added the historical dimension to an understanding of society, culture and economics. Created the concept of ideology in the sense of (true or false) beliefs that shape and control social actions. Analyzed the fundamental nature of class as a mechanism of governance and social interaction. Profoundly influenced world politics with his theory of communism.

- Mencius: One of the most important thinkers in the Confucian school, he is the first theorist to make a coherent argument for an obligation of rulers to the ruled.

- John Stuart Mill: A utilitarian, and the person who named the system; he goes further than Bentham by laying the foundation for liberal democratic thought in general and modern, as opposed to classical, liberalism in particular. Articulated the place of individual liberty in an otherwise utilitarian framework.

- Mikhail Bakunin: After Pierre Joseph Proudhon, Bakunin became the most important political philosopher of anarchism. His specific version of anarchism is called collectivist anarchism.

- Baron de Montesquieu: Analyzed protection of the people by a "balance of powers" in the divisions of a state.

- Mozi: Eponymous founder of the Mohist school, advocated a strict utilitarianism.

- Robert Nozick: Criticized Rawls, and argued for libertarianism, by appeal to a hypothetical history of the state and of property.

- Thomas Paine: Enlightenment writer who defended liberal democracy, the American Revolution, and French Revolution in Common Sense and The Rights of Man.

- Plato: Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the foundations of Western philosophy and science.

- Pierre-Joseph Proudhon: considered the father of modern anarchism, specifically mutualism.

- Ayn Rand: Founder of the philosophical system Objectivism.

- John Rawls: Revitalised the study of normative political philosophy in Anglo-American universities with his 1971 book A Theory of Justice, which uses a version of social contract theory to answer fundamental questions about justice and to criticise utilitarianism.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Analyzed the social contract as an expression of the general will, and controversially argued in favor of absolute democracy where the people at large would act as sovereign.

- Peter Kropotkin, one of the classic anarchist thinkers and the most influential theorist of anarcho-communism

- Carl Schmitt: German political theorist, loosely tied to the Nazis, who developed the concepts of the Friend/Enemy Distinction and the State of exception. Though his most influential books were written in the 1920s, he continued to write prolifically until his death (in academic quasi-exile) in 1985. He heavily influenced 20th century political philosophy both within the Frankfurt School and among others as diverse as Jacques Derrida, Hannah Arendt, and Giorgio Agamben.

- Adam Smith: Often said to have founded modern economics; explained emergence of economic benefits from the self-interested behavior ("the invisible hand") of artisans and traders. While praising its efficiency, Smith also expressed concern about the effects of industrial labor (e.g. repetitive activity) on workers. His work on moral sentiments sought to explain social bonds outside the economic sphere.

- Socrates: Widely considered the founder of Western political philosophy, via his spoken influence on Athenian contemporaries; since Socrates never wrote anything, much of what we know about him and his teachings comes through his most famous student, Plato.

- Baruch Spinoza: Set forth the first analysis of "rational egoism", in which the rational interest of self is conformance with pure reason. To Spinoza's thinking, in a society in which each individual is guided of reason, political authority would be superfluous.

- François-Marie Arouet (Voltaire): French Enlightenment writer, poet, and philosopher famous for his advocacy of civil liberties, including freedom of religion and free trade.

- Max Stirner: an important thinker within anarchism and the main representative of the anarchist current known as individualist anarchism

See also

- Anarchist schools of thought

- Consensus decision making

- Consequentialist justifications of the state

- Egalitarianism

- Majoritarianism

- Panarchism

- Progressivism

- Political media

- Political philosophy of Immanuel Kant

- Political science

- Rechtsstaat

- Rule of law

- Rule According to Higher Law

- The justification of the state

- Sociology

- Theodemocracy

References

- ^ Hampton, Jean (1997). Political philosophy. p. xiii. ISBN 0813308586. http://books.google.com/books?id=-sHkdq5qhFwC&pg=PR13&dq=Hampton+political+philosophy+political+societies#v=onepage&q=Hampton%20political%20philosophy%20political%20societies&f=false. Charles Blattberg, who defines politics as "responding to conflict with dialogue," suggests that political philosophies offer philosophical accounts of that dialogue. See his Political Philosophies and Political Ideologies. SSRN 1755117. in Patriotic Elaborations: Essays in Practical Philosophy, Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2009.

- ^ Deutsch, Eliot; Ronald Bontekoei (1999). A companion to world philosophies. Wiley Blackwell. p. 183.

- ^ Hsü, Leonard Shihlien (2005). The political philosophy of Confucianism. Routledge. pp. xvii-xx. ISBN 0415361545. http://books.google.com/books?id=FWFtQIyun-8C&pg=PR17&dq=political+philosophy+China#v=onepage&q=political%20philosophy%20China&f=false. "The importance of a scientific study of Confucian political philosophy could hardly be overstated."

- ^ a b Sahakian, Mabel Lewis (1993). Ideas of the great philosophers. Barnes & Noble Publishing. p. 59. ISBN 1566192712. http://books.google.com/books?id=Vi7cQMw8SwYC&pg=PA59&dq=political+philosophy+Plato+the+republic#v=onepage&q=political%20philosophy%20Plato%20the%20republic&f=false. "...Western philosophical tradition can be traced back as early as Plato (427-347B.C.)."

- ^ Kraut, Richard (2002). Aristotle: political philosophy. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0198782001. http://books.google.com/books?id=9BDmX3FBbS4C&pg=PA3&dq=political+philosophy+Aristotle+politics#v=onepage&q=political%20philosophy%20Aristotle%20politics&f=false. "To understand and assess Aristotle's contributions to political thought..."

- ^ Radford, Robert T. (2002). Cicero: a study in the origins of republican philosophy. Rodopi. p. 1. ISBN 9042014671. http://books.google.com/books?id=1cKLGcvuYxQC&pg=PA1&dq=political+philosophy+Cicero#v=onepage&q=political%20philosophy%20Cicero&f=false. "His most lasting political contribution is in his work on political philosophy."

- ^ Sir William Jones´s translation is available online as The Institutes of Hindu Law: Or, The Ordinances of Manu, Calcutta: Sewell & Debrett, 1796.

- ^ Schall, James V. (1998). At the Limits of Political Philosophy. CUA Press. p. 40. ISBN 0813209227. http://books.google.com/books?id=yZK79kiFFtsC&pg=PA40&dq=political+philosophy+Saint+Augustine#v=onepage&q=&f=false. "In political philosophy, St. Augustine was a follower of Plato..."

- ^ Aslan, Reza (2005). No god but God. Random House Inc.. p. 153. ISBN 1400062133. http://books.google.com/books?id=FEfdoRL1rrgC&pg=PA153&dq=Islam+Mutazilite+and+Asharite+views#v=onepage&q=&f=false. "By the ninth and tenth centuries..."

- ^ Gellner, Ernest (1992). Plough, Sword, and Book. University of Chicago Press. p. 239. ISBN 0226287027. http://books.google.com/books?id=CwZFV7J7Id8C&pg=PA239&dq=Gellner+Plough+Sword+and+Book+Ibn+Khaldun%27s+definition#v=onepage&q=&f=false. "(Ibn Khaldun's definition of government probably remains the best:...)"

- ^ Koetsier, L. S. (2004). Natural Law and Calvinist Political Theory. Trafford Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 1412007382. http://books.google.com/books?id=2SI0I4t9roEC&pg=PA19&dq=political+philosophy+scholasticism#v=onepage&q=political%20philosophy%20scholasticism&f=false. "...the Medieval Scholastics revived the concept of natural law."

- ^ Copleston, Frederick (1999). A history of philosophy. 3. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 346. ISBN 0860122968. http://books.google.com/books?id=y_382o-fpOsC&pg=PA346&dq=political+philosophy+scholasticism#v=onepage&q=political%20philosophy%20scholasticism&f=false. "There was, however, at least one department of thought..."

- ^ Valente, Claire (2003). The theory and practice of revolt in medieval England. Ashgate Publishing Ltd.. p. 14. ISBN 0754609018. http://books.google.com/books?id=B8yRrtm0LicC&pg=PA14&dq=political+philosophy+medieval+europe#v=onepage&q=&f=false. "The two starting points of most medieval discussions..."

- ^ Johnston, Ian (February 2002). "Lecture on Machiavelli's The Prince". Malaspina University College. http://www.mala.bc.ca/~Johnstoi/introser/machiavelli.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- ^ Copleston, Frederick (1999). A history of philosophy. 3. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 310–312. ISBN 0860122968. http://books.google.com/books?id=y_382o-fpOsC&pg=PA310&dq=political+philosophy+Machiavelli#v=onepage&q=political%20philosophy%20Machiavelli&f=false. "...we witness the growth of political absolutism..."

- ^ Barens, Ingo, ed (2004). Political events and economic ideas. Volker Caspari ed., Bertram Schefold ed.. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 206–207. ISBN 1843764403. http://books.google.com/books?id=zSZyQ9TzqQ0C&pg=PA206&dq=political+philosophy+the+enlightenment#v=onepage&q=politcal%20philosophy%20the%20enlightenment&f=false. "Economic theory as political philosophy: the example of the French Enlightenment"

- ^ Byrne, James M. (1997). Religion and the Enlightenment. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0664257606. http://books.google.com/books?id=FcEy8SF63TgC&pg=PA1&dq=political+philosophy+the+enlightenment+and+religion#v=onepage&q=political%20philosophy%20the%20enlightenment$20and%20religion&f=false. "...there emerged groups of freethinkers intent on grounding knowledge on the exercise of critical reason, as opposed to...established religion..."

- ^ Johansen, Bruce Elliott (1996). Native American political systems and the evolution of democracy. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 69. ISBN 0313300103. http://books.google.com/books?id=H593mgxQNu4C&pg=PA69&dq=Iroquois+philosophy+Benjamin+Franklin#v=onepage&q=Iroquois%20philosophy%20Benjamin%20Franklin&f=false. "...the three-tier system of federalism...is an inheritance of Iroquois inspiration"

- ^ Kain, Philip J. (1993). Marx and modern political theory. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 1–4. ISBN 0847678662. http://books.google.com/books?id=kvG8DVBeT9QC&pg=PA1&dq=political+philosophy+Marx#v=onepage&q=political%20philosophy%20Marx&f=false. "Some of his texts, especially the Communist Manifesto made him seem like a sort of communist Descartes..."

- ^ Aspalter, Christian (2001). Importance of Christian and Social Democratic movements in welfare politics. Nova Publishers. p. 70. ISBN 1560729754. http://books.google.com/books?id=vouKut-RAYoC&pg=PA70&dq=social+democratic+parties+win+universal+suffrage#v=onepage&q=social%20democratic%20parties%20win%20universal%20suffrage&f=false. "The pressing need for universal suffrage..."

- ^ What is Austrian Economics?, Ludwig Von Mises Institute.

- ^ Richard M. Ebeling, Austrian Economics and the Political Economy of Freedom, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2003, 163-179 ISBN 1840649402, 9781840649406.

- ^ David Lewis Schaefer, Robert Nozick and the Coast of Utopia, The New York Sun, April 30, 2008.

- ^ Blattberg, Charles, "Political Philosophies and Political Ideologies," in Patriotic Elaborations: Essays in Practical Philosophy, Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2009.

Further reading

- Academic Journals dedicated to Political Philosophy include: Political Theory, Philosophy and Public Affairs, Contemporary Political Theory, Theory & Event, Constellations, and Journal of Political Philosophy

- The London Philosophy Study Guide offers many suggestions on what to read, depending on the student's familiarity with the subject: Political Philosophy

- Alexander F. Tsvirkun 2008. History of political and legal Teachings of Ukraine. Kharkov.

- Bielskis, Andrius 2005. Towards a Postmodern Understanding of the Political. Basingstoke, New York: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Eric Nelson, “The Hebrew Republic: Jewish Sources and the Transformation of European Political Thought” (Harvard University Press, 2010)

External links

- Video lectures (require Adobe Flash): Introduction to Political Philosophy delivered by Steven B Smith of Yale University and provided by Academic Earth.

Social and political philosophy Philosophers Adi Shankara · Plato · Vaisheshika · Nyāya Sūtras · Augustine · Marsilius · Machiavelli · Grotius · Montesquieu · Comte · Bosanquet · Spencer · Malebranche · Durkheim · Santayana · Royce · Russell · Confucius · Hobbes · Leibniz · Hume · Kant · Rousseau · Locke · Burke · Smith · Bentham · Mill · Thoreau · Marx · Gandhi · Gentile · Maritain · Berlin · Schmitt · Debord · Camus · Sartre · Foucault · Rawls · Popper · Đilas · Habermas · Kirk · Oakeshott · Nozick · Alinsky · Chomsky · Baudrillard · Badiou · Strauss · Rand · Žižek · Walzer

Social theories Social concepts Society · War · Law · Justice · Peace · Rights · Revolution · Civil disobedience · Democracy · Social contract · more...

Related articles Philosophy of economics · Philosophy of education · Philosophy of history · Jurisprudence · Philosophy of social science · Philosophy of love · Philosophy of sex

Jurisprudence Philosophers Alexy • Allan • Amar • Aquinas • Aristotle • Austin • Beccaria • Bentham • Betti • Bickel • Blackstone • Bobbio • Bork • Castanheira Neves • Chafee • Coleman • Del Vecchio • Derrida • Durkheim • Dworkin • Ehrlich • Feinberg • Fineman • Finnis • Fuller • Gardner • George • Green • Grisez • Grotius • Gurvitch • Habermas • Hand • Hart • Hayek • Hegel • Hohfeld • Holmes • Kant • Kelsen • Köchler • Kramer • Llewellyn • Luhmann • Lyons • MacCormick • Marx • Nussbaum • Olivecrona • Petrazycki • Posner • Pound • Radbruch • Rawls • Raz • Reinach • Renner • Savigny • Scaevola • Schmitt • Simmonds • Tribe • Unger • Waldron • WeberTheories Analytical jurisprudence • Deontological ethics • Legal moralism • Legal positivism • Legal realism • Libertarian theories of law • Maternalism • Natural law • Paternalism • Utilitarianism • Virtue jurisprudenceConcepts Related articles Law • Political philosophy • more...Categories:- Political philosophy

- Political theories

- Social philosophy

- Branches of philosophy

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.