- Battle of Midway

-

Battle of Midway Part of the Pacific Theater of World War II

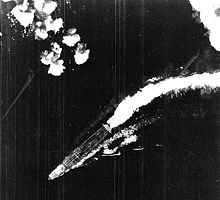

U.S. Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless dive bombers from the USS Hornet about to attack the burning Japanese cruiser Mikuma for the third time on 6 June 1942.Date 4–7 June 1942 Location Midway Atoll

28°12′N 177°21′W / 28.2°N 177.35°WCoordinates: 28°12′N 177°21′W / 28.2°N 177.35°WResult Decisive American victory Belligerents  United States

United States Empire of Japan

Empire of JapanCommanders and leaders Chester W. Nimitz

Frank J. Fletcher

Raymond A. SpruanceIsoroku Yamamoto

Nobutake Kondō

Chūichi Nagumo

Tamon Yamaguchi †

Ryusaku Yanagimoto †Strength 3 carriers,

~25 support ships,

233 carrier aircraft,

127 land-based aircraft4 carriers,

2 battleships,

~15 support ships (heavy and light cruisers, destroyers),

248[1] carrier aircraft, 16 floatplanes

Did not participate in battle:

2 light carriers,

5 battleships,

~41 support ships (Yamamoto "Main Body", Kondo "Strike Force" plus "Escort" and "Occupation Support Force")Casualties and losses 1 carrier sunk,

1 destroyer sunk,

150 aircraft destroyed,[citation needed]

307 killed[2]4 carriers sunk,

1 cruiser sunk,

248 carrier aircraft destroyed,[3]

3,057 killed.[4]Hawaiian Islands CampaignFrench Indochina – Nauru - Thailand – Malaya – Hawaii - America - Hong Kong – Philippines – Guam – Wake – Marshalls & Gilberts - Dutch East Indies – New Guinea – Singapore – Australia – Indian Ocean – Doolittle Raid – Solomons - Coral SeaPacific Ocean theaterHawaii – Marshalls-Gilberts raids – Doolittle Raid – Coral Sea – Midway – Ry – Solomons – Aleutians – Gilberts and Marshalls – Marianas and Palau – Volcano and Ryukyu – CarolinesThe Battle of Midway (Japanese: ミッドウェー海戦) is widely regarded as the most important naval battle of the Pacific Campaign of World War II.[5][6][7] Between 4 and 7 June 1942, approximately one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea and six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States Navy decisively defeated an Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) attack against Midway Atoll, inflicting irreparable damage on the Japanese fleet.[8] Military historian John Keegan has called it "the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare."[9]

The Japanese operation, like the earlier attack on Pearl Harbor, sought to eliminate the United States as a strategic power in the Pacific, thereby giving Japan a free hand in establishing its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The Japanese hoped that another demoralizing defeat would force the U.S. to capitulate in the Pacific War.[10]

The Japanese plan was to lure the United States' aircraft carriers into a trap.[11] The Japanese also intended to occupy Midway Atoll as part of an overall plan to extend their defensive perimeter in response to the Doolittle Raid. This operation was also considered preparatory for further attacks against Fiji and Samoa.

The plan was handicapped by faulty Japanese assumptions of the American reaction and poor initial dispositions.[12] Most significantly, American codebreakers were able to determine the date and location of the attack, enabling the forewarned U.S. Navy to set up an ambush of its own. Four Japanese aircraft carriers and a heavy cruiser were sunk for a cost of one American aircraft carrier and a destroyer. After Midway, and the exhausting attrition of the Solomon Islands campaign, Japan's shipbuilding and pilot training programs were unable to keep pace in replacing their losses while the U.S. steadily increased its output in both areas.[13]

Contents

Strategic context

Japan had attained its initial strategic goals quickly, taking the Philippines, Malaya, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia); the latter, with its vital resources, was particularly important to Japan. Because of this, preliminary planning for a second phase of operations commenced as early as January 1942. However, there were strategic disagreements between the Imperial Army and Imperial Navy, and infighting between the Navy's GHQ and Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto's Combined Fleet, such that a follow-up strategy was not formulated until April 1942.[14] Admiral Yamamoto finally succeeded in winning the bureaucratic struggle by using a thinly veiled threat to resign, after which his operational concept of further operations in the Central Pacific was accepted ahead of other competing plans.[15]

Yamamoto's primary strategic goal was the elimination of America's carrier forces, which he perceived as the principal threat to the overall Pacific campaign.[nb 1] This concern was acutely heightened by the Doolittle Raid (18 April 1942) in which USAAF B-25 Mitchells launched from USS Hornet bombed targets in Tokyo and several other Japanese cities. The raid, while militarily insignificant, was a severe psychological shock to the Japanese and showed the existence of a gap in the defenses around the Japanese home islands.[16][nb 2] This and other successful "hit and run" raids by American carriers, showed that they were still a threat although, seemingly, reluctant to be drawn into an all-out battle.[17] Yamamoto reasoned that another attack on the main U.S base at Pearl Harbor would induce all of the American fleet out to fight, including the carriers; however, given the strength of American land-based air power on Hawaii, he judged that Pearl Harbor could no longer be attacked directly.[18] Instead, he selected Midway, at the extreme northwest end of the Hawaiian Island chain, some 1,300 mi (1,100 nmi; 2,100 km) from Oahu. Midway was not especially important in the larger scheme of Japan's intentions, but the Japanese felt the Americans would consider Midway a vital outpost of Pearl Harbor and would therefore strongly defend it.[19] The U.S. did consider Midway vital; after the battle, establishment of a U.S. submarine base on Midway allowed submarines operating from Pearl Harbor to refuel and reprovision, extending their radius of operations by 1,200 mi (1,900 km). An airstrip on Midway served as a forward staging point for bomber attacks on Wake Island.[20]

Yamamoto's plan, Operation Mai

Typical of Japanese naval planning during World War II, Yamamoto's battle plan was exceedingly complex.[21] Additionally, his design was predicated on optimistic intelligence suggesting USS Enterprise and USS Hornet, forming Task Force 16, were the only carriers available to the U.S. Pacific Fleet at the time. At the Battle of the Coral Sea just a month earlier, USS Lexington had been sunk and USS Yorktown damaged severely enough that the Japanese believed it also to have been sunk. The Japanese were also aware that USS Saratoga was undergoing repairs on the West Coast after suffering torpedo damage from a submarine.

However, more important was Yamamoto's belief the Americans had been demoralized by their frequent defeats during the preceding six months. Yamamoto felt deception would be required to lure the U.S. fleet into a fatally compromised situation.[22] To this end, he dispersed his forces so that their full extent (particularly his battleships) would be unlikely to be discovered by the Americans prior to battle. Critically, Yamamoto's supporting battleships and cruisers would trail Vice-Admiral Nagumo Chūichi's carrier striking force by several hundred miles. Japan's heavy surface forces were intended to destroy whatever part of the U.S. fleet might come to Midway's relief, once Nagumo's carriers had weakened them sufficiently for a daylight gun duel;[23] this was typical of the battle doctrine of most major navies.[24]

Yamamoto did not know that the U.S. had broken the main Japanese naval code (dubbed JN-25 by the Americans). Yamamoto's emphasis on dispersal also meant that none of his formations could support each other. For instance, the only significant warships larger than destroyers that screened Nagumo's fleet were two battleships and three cruisers, despite his carriers being expected to carry out the strikes and bear the brunt of American counterattacks. By contrast, the flotillas of Yamamoto and Kondo had between them two light carriers, five battleships, and six cruisers, none of which would see any action at Midway.[23] Their distance from Nagumo's carriers would also have grave implications during the battle, because the larger warships in Yamamoto and Kondo's forces carried scout planes, an invaluable reconnaissance capability denied to Nagumo.[25][26]

Aleutian invasion

Main article: Aleutian Islands CampaignLikewise, the Japanese operations in the Aleutian Islands (Operation AL) removed yet more ships that could otherwise have augmented the force striking Midway. Whereas prior historical accounts have often characterized the Aleutians operation as a feint to draw American forces away, recent scholarship on the battle has suggested that AL was supposed to be launched simultaneously with the attack on Midway.[24] However, a one-day delay in the sailing of Nagumo's task force meant that Operation AL began a day before the Midway attack.[27]

Prelude to battle

American reinforcements

To do battle with an enemy force anticipated to muster four or five carriers, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas, needed every available U.S. flight deck. He already had Vice Admiral William Halsey's two-carrier (Enterprise and Hornet) task force at hand, though Halsey was stricken with psoriasis and had to be replaced by Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, Halsey's escort commander.[28] Nimitz also hurriedly recalled Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher's task force, including the carrier Yorktown (which had suffered considerable damage at Coral Sea), from the South West Pacific Area. It reached Pearl Harbor just in time to provision and sail.

Despite estimates that Yorktown would require several months of repairs at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, her elevators were intact, and her flight deck largely so.[29] The Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard worked around the clock and in 72 hours, she was restored to a battle-ready state,[30] judged good enough for two or three weeks of operations, as Nimitz required.[31] Her flight deck was patched, whole sections of internal frames cut out and replaced, and several new squadrons were drawn from Saratoga; they did not, however, get time to train.[32] Nimitz disregarded established procedure in getting his third and last available carrier ready for battle. Just three days after putting into dry dock at Pearl Harbor, Yorktown was again under way. Repairs continued even as she sortied, with work crews from the repair ship USS Vestal, herself damaged in the attack on Pearl Harbor six months earlier, still aboard.[33]

On Midway Island, the USAAF stationed four squadrons of B-17 Flying Fortresses, along with several B-26 Marauders. The Marine Corps had 19 SBD Dauntlesses, seven F4F-3 Wildcats, 17 Vought SBU-3 Vindicators, 21 Brewster F2A-3s, and six Grumman TBF-1 Avengers, the latter a detachment of VT-8 from Hornet.

Japanese shortcomings

Akagi, the flagship of the Japanese carrier striking force which attacked Pearl Harbor, as well as Darwin, Rabaul, and Colombo, in April 1942 prior to the battle.

Akagi, the flagship of the Japanese carrier striking force which attacked Pearl Harbor, as well as Darwin, Rabaul, and Colombo, in April 1942 prior to the battle.

Meanwhile, as a result of her participation in the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Japanese carrier Zuikaku was in port in Kure, awaiting a replacement air group. That there were none immediately available was a failure of the IJN crew training program, which already showed signs of being unable to replace losses.[34] Instructors from the Yokosuka Air Corps were employed in an effort to make up the shortfall.[34] The heavily damaged Shōkaku had suffered three bomb hits at Coral Sea, and required months of repair in drydock. Despite the likely availability of sufficient aircraft between the two ships to re-equip Zuikaku with a composite air group, the Japanese made no serious attempt to get her into the forthcoming battle.[35] Consequently, Admiral Nagumo would only have four fleet carriers: Kaga and Akagi forming Carrier Division 1; Hiryū and Sōryū as Carrier Division 2. At least part of this was a product of fatigue; Japanese carriers had been constantly on operations since 7 December 1941, including raids on Darwin and Colombo.

The main Japanese strike aircraft to be used were the Aichi D3A1 "Val" dive bomber and the Nakajima B5N2 "Kate", which was capable of being used either as a torpedo bomber or as a level attack bomber. The main carrier fighter was the fast and highly maneuverable Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero.[nb 3] However, the carriers of the Kido Butai were suffering from a shortage of frontline aircraft. For various reasons, production of the "Val" had been drastically reduced, while that of the B5N had been stopped completely.[36] As a consequence, there were none available to replace losses. This also meant that many of the aircraft being used during the June 1942 operations had been operational since late November 1941; although well maintained, they were almost worn out and had become increasingly unreliable. These factors meant that all carriers had fewer than their normal aircraft complement and few spare aircraft.[37]

Japanese strategic scouting arrangements prior to the battle were also in disarray. A picket line of Japanese submarines was late getting into position (partly because of Yamamoto's haste), which let the American carriers reach their assembly point northeast of Midway (known as "Point Luck") without being detected.[38] A second attempt at reconnaissance, using four-engine Kawanishi H8K "Emily" flying boats to scout Pearl Harbor prior to the battle (and thereby detect the absence or presence of the American carriers), part of Operation K, was also thwarted when Japanese submarines assigned to refuel the search aircraft discovered that the intended refueling point — a hitherto deserted bay off French Frigate Shoals — was occupied by American warships (because the Japanese had carried out an identical mission in March).[39] Thus, Japan was deprived of any knowledge concerning the movements of the American carriers immediately before the battle.

Japanese radio intercepts did notice an increase in both American submarine activity and message traffic. This information was in Yamamoto's hands prior to the battle. However, Japanese plans were not changed; Yamamoto, at sea on Yamato, did not dare inform Nagumo for fear of exposing his position and assumed that Nagumo had received the same signal from Tokyo.[40] Nagumo's radio antennae, however, were unable to receive such long-wave transmissions, and he was left unaware of any American ship movements.[41]

Allied code-breaking

Admiral Nimitz had one priceless asset: cryptanalysts had broken the JN-25 code.[42] Since the early spring of 1942, the US had been decoding messages stating that there would soon be an operation at objective "AF." Commander Joseph J. Rochefort and his team at Station Hypo were able to confirm Midway as the target of the impending Japanese strike by having the base at Midway send a false message stating that its water distillation plant had been damaged and that the base needed fresh water. The Japanese saw this and soon started to send messages stating that "AF was short on water."[43] Hypo was also able to determine the date of the attack as either 4 or 5 June, and to provide Nimitz with a complete IJN order of battle.[44] Japan's efforts to introduce a new codebook had been delayed, giving HYPO several crucial days; while it was blacked out shortly before the attack began, the important breaks had already been made.[45][nb 4]

As a result, the Americans entered the battle with a very good picture of where, when, and in what strength the Japanese would appear. Nimitz was aware, for example, that the vast Japanese numerical superiority had been divided into no less than four task forces. This dispersal resulted in few fast ships being available to escort the Carrier Striking Force, limiting the anti-aircraft guns protecting the carriers. Nimitz thus calculated that his three carrier decks, plus Midway Island, to Yamamoto's four, gave the U.S. rough parity, especially since American carrier air groups were larger than Japanese ones. The Japanese, by contrast, remained almost totally unaware of their opponent's true strength and dispositions even after the battle began.[26]

Battle

Order of battle

Main article: Midway order of battleInitial air attacks

The first air attack took off at 12:30 on 3 June, consisting of nine B-17s operating from Midway. Three hours later, they found the Japanese transport group 570 nmi (660 mi; 1,060 km) to the west.[46] Under heavy anti-aircraft fire, they dropped their bombs. Though hits were reported,[46] none of the bombs actually landed on target and no significant damage was inflicted.[47] Early the following morning, Japanese oil tanker Akebono Maru sustained the first hit when a torpedo from an attacking PBY flying boat struck her around 01:00. This would be the only successful air launched torpedo attack by the U.S. during the entire battle.[47]

At 04:30 on 4 June, Nagumo launched his initial attack on Midway itself, consisting of 36 Vals and 36 Kates, escorted by 36 Zeros. At the same time, he launched combat air patrol (CAP), as well as his eight search aircraft (one from the heavy cruiser Tone launched 30 minutes late due to technical difficulties).

Japanese reconnaissance arrangements were flimsy, with too few aircraft to adequately cover the assigned search areas, laboring under poor weather conditions to the northeast and east of the task force.[48] Yamamoto's faulty dispositions had now become a serious liability.[49]

American radar picked up the enemy at a distance of several miles and interceptors were soon scrambled. Unescorted bombers headed off to attack the Japanese carrier fleet, their fighter escorts remaining behind to defend Midway. At 06:20, Japanese carrier aircraft bombed and heavily damaged the U.S. base. Midway-based Marine fighter pilots, flying F4F-3 Wildcats and obsolete Brewster F2A-3 Buffalos,[50] intercepted the Japanese and suffered heavy losses, though they managed to destroy four "Val"s and at least three Zeros. Most of the U.S. planes were downed in the first few minutes; several were damaged, and only two remained flyable. In all, three F4Fs and 13 F2As were shot down. American anti-aircraft fire was accurate and intense, damaging many Japanese aircraft and claiming one-third of the Japanese planes destroyed.[51]

The initial Japanese attack did not succeed in neutralizing Midway. American bombers could still use the airbase to refuel and attack the Japanese invasion force; another aerial attack would be necessary if troops were to go ashore by 7 June.[52]

Having taken off prior to the Japanese attack, American bombers based on Midway made several attacks on the Japanese carrier fleet. These included six TBFs from Hornet's VT-8, their crews on their first combat operation, and four USAAF B-26 Marauders armed with torpedoes. The Japanese shrugged off these attacks with almost no losses (as few as two fighters lost), while destroying all but one TBF and two B-26s. One B-26, hit by anti-aircraft fire from Akagi, made no attempt to pull out of its run and narrowly missed crashing directly into the carrier's bridge. This experience may well have contributed to Nagumo's determination to launch another attack on Midway, in direct violation of Yamamoto's order to keep the reserve strike force armed for anti-ship operations.[53]

B-17 attack misses Hiryū; this was taken some time between 08:00–08:30. A Shotai of three Zeros is lined up near the bridge. This was one of several CAPs (Combat Air Patrols) launched during the day.[54]

B-17 attack misses Hiryū; this was taken some time between 08:00–08:30. A Shotai of three Zeros is lined up near the bridge. This was one of several CAPs (Combat Air Patrols) launched during the day.[54]

Nagumo's decision

Admiral Nagumo, in accordance with Japanese carrier doctrine at the time, had kept half of his aircraft in reserve. These comprised two squadrons each of dive bombers and torpedo bombers, the latter armed with torpedoes, should any American warships be located. The dive bombers were, as yet, unarmed.[55] As a result of the attacks from Midway, as well as the morning flight leader's recommendation of a second strike, at 07:15, Nagumo ordered his reserve planes to be re-armed with contact-fused general purpose bombs for use against land targets. Some sources maintain that this had been underway for about 30 minutes when, at 07:40[56] the delayed scout plane from Tone signaled the discovery of a sizable American naval force to the east; however, new evidence suggests Nagumo did not receive the sighting report until 08:00, so the rearming operation actually proceeded for 45 minutes.[57] Nagumo quickly reversed his order and demanded the scout plane ascertain the composition of the American force. Another 40 minutes elapsed before Tone's scout finally radioed the presence of a single carrier in the American force, TF 16 (the other carrier being missed).[58]

Nagumo was now in a quandary. Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi, leading Carrier Division 2 (Hiryū and Sōryū), recommended Nagumo strike immediately with the forces at hand: 18 Aichi D3A2 dive bombers each on Sōryū and Hiryū, and half the ready cover patrol aircraft.[59] Nagumo's seeming opportunity to hit the American ships,[60] however, was now limited by the fact that his Midway strike force would be returning shortly and needing to land promptly or ditch (as is commonly believed).[61] Because of the constant flight deck activity associated with combat air patrol operations during the preceding hour, the Japanese never had an opportunity to "spot" (position) their reserve for launch. The few aircraft on the Japanese flight decks at the time of the attack were either defensive fighters, or (in the case of Sōryū) fighters being spotted to augment the task force defenses.[62] Spotting his flight decks and launching aircraft would have required at least 30–45 minutes.[63] Furthermore, by spotting and launching immediately, Nagumo would be committing some of his reserve to battle without proper anti-ship armament; he had just witnessed how easily unescorted American bombers had been shot down.[64] (In the event, poor discipline saw many of the Japanese bombers ditch their bombs and attempt to dogfight intercepting F4Fs.)[65] Japanese carrier doctrine preferred fully constituted strikes, and without confirmation (until 08:20) of whether the American force included carriers, Nagumo's reaction was doctrinaire.[66] In addition, the arrival of another American air strike at 07:53 gave weight to the need to attack the island again. In the end, Nagumo chose to wait for his first strike force to land, then launch the reserve, which would by then be properly armed and ready.[67]

In the final analysis, it made no difference; Fletcher's carriers had launched beginning at 07:00, so the aircraft which would deliver the crushing blow were already on their way. There was nothing Nagumo could do about it. This was the fatal flaw of Yamamoto's dispositions: they followed strictly traditional battleship doctrine.[68]

Attacks on the Japanese fleet

Ensign George Gay (right), sole survivor of VT-8's TBD Devastator squadron, in front of his aircraft, 4 June 1942.

Ensign George Gay (right), sole survivor of VT-8's TBD Devastator squadron, in front of his aircraft, 4 June 1942.

Devastators of VT-6 aboard USS Enterprise being prepared for take off during the battle.

Devastators of VT-6 aboard USS Enterprise being prepared for take off during the battle.

Meanwhile, the Americans had already launched their carrier aircraft against the Japanese. Admiral Fletcher, in overall command aboard Yorktown, and benefiting from PBY patrol bomber sighting reports from the early morning, ordered Spruance to launch against the Japanese as soon as was practical, while initially holding Yorktown in reserve should there be any other Japanese carriers discovered.[69] Fletcher's directions to Spruance were relayed via Nimitz who, unlike Yamamoto, had remained ashore. Spruance gave the order "Launch the attack" at around 06:00 and left Halsey's Chief of Staff, Captain Miles Browning, to work out the details and oversee the launch. It took until a few minutes after 07:00 before the first plane was able to depart from Spruance's carriers, Enterprise and Hornet. Fletcher, upon completing his own scouting flights, followed suit at 08:00 from Yorktown.[70]

Fletcher, Yorktown's commanding officer Captain Elliott Buckmaster, and their staffs had acquired first-hand experience in organizing and launching a full strike against an enemy force at Coral Sea, but there was no time to pass these lessons to Enterprise and Hornet which were tasked with launching the first strike.[71] Spruance gave his second crucial command, to run toward the target quickly, as neutralizing an enemy carrier was the key to their own carriers' survival. He judged that the need to throw something at the enemy as soon as possible was greater than the need for a coordinated attack among the different types of aircraft (fighters, bombers, torpedo planes). Accordingly, American squadrons were launched piecemeal and proceeded to the target in several different groups. The lack of coordination was expected to diminish the overall impact of the American attacks as well as increasing their casualties. However, Spruance calculated that this risk was worth it, since keeping the Japanese under aerial attack hampered their ability to launch a counterstrike (Japanese doctrine preferred fully constituted attacks), and he gambled that he could find Nagumo with his decks at their most vulnerable.[70][71]

American carrier aircraft had difficulty locating the target, despite the positions they had been given. The strike from Hornet, led by Commander Stanhope C. Ring, followed an incorrect heading of 263 degrees rather than the 240 heading indicated by the contact report. As a result, Air Group Eight's dive bombers missed the Japanese carriers.[72] Torpedo Squadron 8 (VT-8, from Hornet), led by Lieutenant Commander John C. Waldron broke formation from Ring and followed the correct heading. Waldron's squadron sighted the enemy carriers and began attacking at 09:20, followed by Torpedo Squadron 6 (VT-6, from Enterprise) at 09:40.[73] Without fighter escort, all fifteen TBD Devastators of VT-8 were shot down without being able to inflict any damage, with Ensign George H. Gay, Jr. the only survivor. VT-6 met nearly the same fate, with no hits to show for its effort, thanks in part to the abysmal performance of their Mark 13 aircraft torpedoes;[74] senior Navy and BuOrd officers never questioned why half a dozen torpedoes, released so close to the Japanese carriers, produced no results.[75] The Japanese combat air patrol, flying the much faster Mitsubishi A6M2 "Zeros", made short work of the unescorted, slow, under-armed TBDs. A few TBDs managed to get within a few ship-lengths range of their targets before dropping their torpedoes, being close enough to be able to strafe the enemy ships and force the Japanese carriers to make sharp evasive maneuvers.[76]

Despite their losses, the American torpedo attacks indirectly achieved three important results. First, they kept the Japanese carriers off balance, with no ability to prepare and launch their own counterstrike. Second, their attacks pulled the Japanese combat air patrol out of position. Third, many of the Zeros ran low on ammunition and fuel.[77] The appearance of a third torpedo plane attack from the southeast by Torpedo Squadron 3 (VT-3) at 10:00 very quickly drew the majority of the Japanese CAP to the southeast quadrant of the fleet.[78] Better discipline, and employment of all the Zeroes aboard, might have enabled Nagumo to succeed.[79]

By chance, at the same time VT-3 was sighted by the Japanese, three squadrons of American SBDs from Enterprise and Yorktown, VB-6, VS-6 and VB-3 respectively, were approaching the Japanese fleet from the northeast and southwest. They were running low on fuel because of the time spent looking for the enemy. However, squadron commander C. Wade McClusky, Jr. decided to continue the search and by good fortune saw the wake of the Japanese destroyer Arashi. The destroyer was steaming at full speed to rejoin Nagumo's carrier force after having unsuccessfully depth-charged the U.S. submarine Nautilus, which had earlier unsuccessfully attacked the battleship Kirishima.[80] Some bombers were lost from fuel exhaustion before the attack commenced.[81]

McClusky's decision to continue the search was credited by Admiral Chester Nimitz, and his judgment "decided the fate of our carrier task force and our forces at Midway...."[82] The American dive-bombers arrived at the perfect time to attack.[83] Armed Japanese strike aircraft filled the hangar decks, fuel hoses snaked across the decks as refueling operations were hastily completed, and the repeated change of ordnance meant bombs and torpedoes were stacked around the hangars, rather than stowed safely in the magazines,[84] making the Japanese carriers extraordinarily vulnerable.

Enterprise's VB-6 and VS-6 air group split up and attacked two targets. Beginning at 10:22, McClusky and his wingmen scored hits on Kaga, while to the north Akagi was attacked four minutes later by three bombers,[76] led by Lieutenant Commander Richard Halsey Best. Yorktown's VB-3 commanded by Max Leslie went for Sōryū scoring hits. Simultaneously, VT-3 targeted Hiryū, which was sandwiched between Sōryū, Kaga, and Akagi, but scored no hits. The dive-bombers, within six minutes, left Sōryū and Kaga ablaze. Akagi was hit by just one bomb (dropped by LCDR Best), which penetrated to the upper hangar deck and exploded among the armed and fueled aircraft there. One bomb exploded underwater very close astern, the resulting geyser bending the flight deck upward and also causing crucial rudder damage.[nb 5] Sōryū took three bombs in her hangar deck; Kaga, at least four, possibly five. All three carriers were out of action and were eventually abandoned and scuttled.[85]

Japanese counterattacks

Hiryū, the sole surviving Japanese aircraft carrier, wasted little time in counterattacking. The first wave of Japanese dive bombers badly damaged Yorktown with three bomb hits that snuffed out her boilers, immobilizing her, yet her damage control teams patched her up so effectively (in about an hour) that the second wave's torpedo bombers mistook her for an undamaged carrier.[86] Despite Japanese hopes to even the odds by eliminating two carriers with two strikes, Yorktown absorbed both Japanese attacks, the second wave mistakenly believing Yorktown had already been sunk and that they were attacking Enterprise. After two torpedo hits, Yorktown lost power and developed a 26° list to port, which put her out of action and forced Admiral Fletcher to move his command staff to the heavy cruiser Astoria. Both carriers of Spruance's Task Force 16 were undamaged.[87]

News of the two strikes, with the reports that each had sunk an American carrier, greatly improved morale in the Kido Butai. Its few surviving aircraft were all recovered aboard Hiryū, where they were prepared for a strike against what was believed to be the only remaining American carrier.[88]

Late in the afternoon, a Yorktown scout aircraft located Hiryū, prompting Enterprise to launch a final strike of dive bombers (including 10 bombers from Yorktown). This delivered a killing blow, leaving Hiryū ablaze, despite being defended by a strong cover of more than a dozen Zero fighters. Rear Admiral Yamaguchi chose to go down with his ship when she sank on 5 June, costing Japan perhaps her best carrier sailor. Hornet's strike, launching late because of a communications error, concentrated on the remaining escort ships, but failed to score any hits.[89]

As darkness fell, both sides took stock and made tentative plans for continuing the action. Admiral Fletcher, obliged to abandon derelict Yorktown and feeling he could not adequately command from a cruiser, ceded operational command to Spruance. Spruance knew the United States had won a great victory, but was still unsure of what Japanese forces remained and was determined to safeguard both Midway and his carriers. To aid his aviators, who had launched at extreme range, he had continued to close with Nagumo during the day, and persisted as night fell. Fearing a possible night encounter with Japanese surface forces,[90] Spruance changed course and withdrew to the east, turning back west towards the enemy at midnight.

For his part, Yamamoto initially decided to continue the engagement and sent his remaining surface forces searching eastward for the American carriers. Simultaneously, a cruiser raiding force was detached to bombard the island. The Japanese surface forces failed to make contact with the Americans due to Spruance's decision to briefly withdraw eastward, and Yamamoto ordered a general retirement to the west.[91]

American search planes failed to detect the retiring Japanese task forces on 5 June. An afternoon strike narrowly missed detecting Yamamoto's main body and failed to score hits on a straggling Japanese destroyer. The strike planes returned to the carriers after nightfall, prompting Spruance to order Enterprise and Hornet to turn on searchlights in order to aid their landings.[nb 6]

At 02:15 on 5/6 June, Commander John Murphy's Tambor, lying some 90 nmi (100 mi; 170 km) west of Midway, made the second of the Submarine Force's two major contributions to the battle's outcome. Sighting several ships, he (along with his exec, Ray Spruance, Jr.) could not identify them (and feared they might be friendly, so he held fire), but reported their presence, omitting their course. This went to Admiral Robert English, Commander, Submarine Force, Pacific Fleet (COMSUBPAC), and from him through Nimitz to the senior Spruance. Unaware of the exact location of Yamamoto's "Main Body" (a persistent problem since PBYs had first sighted the Japanese), Spruance presumed this was the invasion force. Thus, he moved to block it, taking station some 100 nmi (120 mi; 190 km) northeast of Midway; this frustrated Yamamoto's efforts, and the night passed without any contact between the opposing forces.[92]

Actually, this was Yamamoto's bombardment group of four cruisers and two destroyers, which at 02:55 was ordered to retire west with the rest of his force.[92] Tambor was sighted around the same time; turning to avoid her, Mogami and Mikuma collided, inflicting serious damage to Mogami's bow, the most any of the 18[93] submarines deployed for the battle achieved. Only at 04:12 did the sky brighten enough for Murphy to be certain the ships were Japanese, by which time staying surfaced was a hazard, and he dived to approach for an attack. This was unsuccessful, and at around 06:00, he finally reported two Mogami-class cruisers, westbound, placing Spruance at least 100 nmi (120 mi; 190 km) out of position.[94] It may have been fortunate Spruance did not pursue, for had he come in contact with Yamamoto's heavy ships, including Yamato, in the dark, his cruisers would have been overwhelmed, and his carriers helpless.[95] (At that time, only Britain's Fleet Air Arm was capable of night carrier operations.)[nb 7]

Over the following two days, first Midway and then Spruance's carriers launched several successive strikes against the stragglers. Mikuma was eventually sunk by Dauntlesses,[96] while Mogami survived severe damage to return home for repairs. Captain Richard E. Fleming, a U.S. Marine Corps aviator, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his attack on Mikuma. Another Marine aviator, Major Lofton Henderson, killed while leading his squadron into action against the Japanese carriers and becoming the first Marine aviator to perish during the battle, was also honored, by having the airfield at Guadalcanal named after him in August 1942.[97]

Meanwhile, salvage efforts on Yorktown were encouraging and she was taken in tow by USS Vireo, until late afternoon on 6 June when Yorktown was struck by two torpedoes from I-168. There were few casualties aboard Yorktown, since most of the crew had already been evacuated, but a third torpedo from this salvo also struck and sank the destroyer USS Hammann, which had been providing auxiliary power to Yorktown. Hammann broke in two with the loss of 80 lives, most due to her own depth charges exploding. Yorktown lingered until just after 05:00 on 7 June.[98]

Japanese Casualties

By the time the battle ended, 3,057 Japanese had died. The four carriers sunk and their casualties were: Akagi: 267; Kaga: 811; Hiryu: 392; Soryu: 711; a combined total of 2,181.[99] The heavy cruisers Mikuma (sunk): 700; and Mogami (badly damaged): 92; between them took a total of 792 casualties.[100]

In addition, the destroyers Arashio (bombed): 35; and Asashio (strafed by aircraft): 21; were both attacked while escorting the damaged heavy cruisers. Floatplanes were lost from the cruisers Chikuma: 3; and Tone: 2. Dead aboard the destroyers Tanikaze: 11; Arashi: 1; Kazagumo: 1; and the fleet oiler Akebono Maru: 10; make up the remaining 23 casualties.[nb 8]

Aftermath

After winning a clear victory, and as pursuit became too hazardous near Wake,[101] American forces retired. Historian Samuel E. Morison wrote in 1949 that Spruance was subjected to much criticism for not pursuing the retreating Japanese, and allowing the retreating Japanese surface fleet to escape.[102] Clay Blair argued in 1975 that had Spruance pressed on, he would have been unable to launch his aircraft after nightfall, and his cruiser escorts would have been overwhelmed by Yamamoto's larger and more powerful surface units, including Yamato.[101] And with his torpedo bombers lost it is doubtful that his aircraft would have been effective against battleships.[citation needed]

On 10 June, the Imperial Japanese Navy conveyed to the military liaison conference an incomplete picture of the results of the battle. Chūichi Nagumo's detailed battle report was submitted to the high command 15 June. It was intended only for the highest echelons in the Japanese Navy and government, and was guarded closely throughout the war. In it, one of the more striking revelations is the comment on the Mobile Force Commander's (Nagumo's) estimates: "The enemy is not aware of our plans (we were not discovered till early in the morning of the 5th at the earliest)."[103] The Japanese public were kept in the dark as to the extent of the defeat, as was much of the military command structure. Japanese news announced a great victory. Only Emperor Hirohito and the highest Navy command personnel were accurately informed of the carrier and pilot losses. Subsequently, Army planners continued to believe, for at least a short time, that the fleet was in good condition.[104]

On the return of the Japanese fleet to Hashirajima on 14 June the wounded were immediately transferred to naval hospitals; most were classified as "secret patients", placed in isolation wards and quarantined from other patients and their own families to prevent the secret of this major defeat from getting out to the general populace.[105] The remaining officers and men were quickly dispersed to other units of the fleet and, with no chance to see family or friends, were shipped to units in the South Pacific where the majority died.[106] By contrast none of the flag officers or staff of the Combined Fleet were penalized, with Nagumo later being placed in command of the rebuilt carrier force.[107]

The Japanese Navy did learn some lessons from Midway: new procedures were adopted whereby more aircraft were refueled and re-armed on the flight deck, rather than in the hangars, and the practice of draining all unused fuel lines was adopted. The new carriers being built were redesigned to incorporate only two flight deck elevators and new firefighting equipment. More carrier crew members were trained in damage-control and firefighting techniques, although the losses later in the war of Shōkaku, Hiyō and Taihō showed that there were still problems in this area.[108] Replacement pilots went through an abbreviated training regimen, meeting the short-term needs of the fleet; however, this led to a decline in the quality of training. These inexperienced pilots were fed into front-line units, while the veterans who remained after Midway and the Solomons campaign were forced to share an increased workload in increasingly desperate conditions, with few being given a chance to rest in rear areas or in the home islands. As a result, Japanese naval air groups progressively declined in overall quality during the war.[109]

Allegations of war crimes

Three U.S. airmen, Ensign Wesley Osmus (pilot, Yorktown), Ensign Frank O'Flaherty (pilot, Enterprise) and Aviation Machinist's Mate B. F. (or B. P.) Gaido (radioman-gunner of O'Flaherty's SBD) were captured by the Japanese during the battle. Osmus was held on the Arashi, with O'Flaherty and Gaido on the cruiser Nagara (or destroyer Makigumo, sources vary), and it is alleged they were later killed.[110] The report filed by Admiral Nagumo states of Ensign Osmus, "He died on 6 June and was buried at sea". Nagumo recorded obtaining seven items of information, including the enemy's strength, but did not mention the death of O'Flaherty or Gaido.[111] O'Flaherty and Gaido were tied to five-gallon kerosene cans filled with water and dumped overboard at unknown date several days or more after the battle.[112]

Impact

The battle has often been called "the turning point of the Pacific".[113] However, the Japanese continued to try to advance in the South Pacific, and it was many more months before the U.S. moved from a state of naval parity to one of increasingly clear supremacy.[114] Thus, although Midway was the Allies' first major victory against the Japanese, it did not change the course of the war in the same sense as Salamis; instead, it was the cumulative attrition of Midway, combined with that of the inconclusive Coral Sea battle, which reduced Japan's ability to undertake major offensives.[8] Midway also paved the way for the landings on Guadalcanal and the prolonged attrition of the Solomon Islands campaign, which allowed the Allies to take the strategic initiative and swing to the offensive for the rest of the Pacific War.[115]

The battle showed the worth of pre-war naval cryptologic training and efforts. These efforts continued and were expanded throughout the war in both the Pacific and Atlantic theaters. Successes were numerous and significant. For instance, the shooting down of Admiral Yamamoto's airplane was possible only because of navy cryptanalysis.

Some authors have stated heavy losses in carriers and veteran aircrews at Midway permanently weakened the Imperial Japanese Navy.[116] Parshall and Tully, however, have pointed out that the losses in veteran aircrew, while heavy (110, just under 25% of the aircrew embarked on the four carriers),[117] was not crippling to the Japanese naval air-corps as a whole: the Japanese navy had some 2,000 carrier qualified aircrew at the start of the Pacific war.[118] A few months after Midway, the JNAF sustained similar casualty rates at both the Battle of the Eastern Solomons and Battle of Santa Cruz, and it was these battles, combined with the constant attrition of veterans during the Solomons campaign, which were the catalyst for the sharp downward spiral in operational capability.[119] However, the loss of four large fleet carriers, and over 40% of the carriers' highly trained aircraft mechanics and technicians, plus the essential flight-deck crews and armorers, and the loss of organizational knowledge embodied by such highly trained crew, were heavy blows to the Japanese carrier fleet.[119][nb 9] The loss of the carriers meant that only Shōkaku and Zuikaku were left for offensive actions. Of Japan's other carriers, Taihō was the only Fleet carrier worth teaming with Shōkaku and Zuikaku, while Ryūjō, Junyo, and Hiyō, were second-rate ships of comparatively limited effectiveness.[120] By the time of the Battle of the Philippine Sea, while the Japanese had somewhat rebuilt their carrier forces, the planes were largely flown by inexperienced pilots so the carrier fleet was not as potent a striking force as it was before Midway. [nb 10]

In the time it took Japan to build three carriers, the U.S. Navy commissioned more than two dozen fleet and light fleet carriers, and numerous escort carriers.[121] By 1942, the United States was already three years into a shipbuilding program, mandated by the Second Vinson Act, intended to make the navy larger than Japan's.[122] The greater part of USN aviators survived the Battle of Midway and subsequent battles of 1942, and combined with growing pilot training programs, the US was able to develop a large number of skilled pilots to complement its material advantages in ships and planes.

Discovery of sunken vessels

Mikuma shortly before sinking

Mikuma shortly before sinking

Because of the extreme depth of the ocean in the area of the battle (more than 17,000 ft (5,200 m)), researching the battlefield has presented extraordinary difficulties. However, on 19 May 1998, Robert Ballard and a team of scientists and Midway veterans from both sides located and photographed (artist's rendering) Yorktown. The ship was remarkably intact for a vessel that sank in 1942; much of the original equipment and even the original paint scheme were still visible.[123]

Ballard's subsequent search for the Japanese carriers was ultimately unsuccessful. In September 1999, a joint expedition between Nauticos Corp. and the U.S. Naval Oceanographic Office searched for the Japanese aircraft carriers. Using advanced renavigation techniques in conjunction with the ship's log of the submarine USS Nautilus, the expedition located a large piece of wreckage, subsequently identified as having come from the upper hangar deck of Kaga.[124] The main wreck, however, has yet to be located.

Other remembrances

Chicago Municipal Airport, important to the war efforts in World War II, was renamed Chicago Midway International Airport (or simply Midway Airport) in 1949 in honor of the battle.

Waldron Field, an outlying training landing strip, at Corpus Christi NAS as well Waldron Road leading to the strip, was named in honor of the commander of USS Hornet's Torpedo Squadron 8. Yorktown Blvd leading away from the strip was named for the U.S. carrier sunk in the battle.

An escort carrier, USS Midway (CVE-63) was commissioned on 17 August 1943. She was renamed St. Lo on 10 October 1944 to clear the name Midway for a large fleet aircraft carrier, USS Midway (CV-41), commissioned on 10 September 1945 (eight days after the Japanese surrender). The latter ship is now docked in San Diego, California and is in use as the USS Midway Museum.

See also

- First Bombardment of Midway, a 7 December 1941 attack on Midway by two Japanese destroyers

References

Footnotes

- ^ In fact, U.S. submarines were more dangerous to Japan's efforts. Blair, Silent Victory passim; Parillo, Japanese Merchant Marine.

- ^ Apparently, because of poor IJN ASW training and doctrine, the Japanese ignored the presence of American submarines off their coast, beginning with Joe Grenfell's Gudgeon which arrived some three weeks after Pearl Harbor. Blair, Silent Victory, p.110; Parillo, Japanese Merchant Marine; Peattie & Evans, Kaigun.

- ^ The code names "Val", "Kate" and "Zeke", which are often applied to these aircraft, were not introduced until late 1943 by the Allied forces. The D3A was normally referred to as Type 99 navy dive bomber, the B5N as the Type 97 navy torpedo bomber and the A6M as the Type 0 navy fighter; it was also known as the "Zero". Parshall and Tully Shattered Sword pp.78–80.

- ^ There are occasional references to "deception", notably in the film Midway, referring to the false traffic before Pearl Harbor; this reflects a complete misunderstanding of the issue.

- ^ Other sources claim a stern hit, but Parshall and Tully in Shattered Sword, pp.253–354 and 256–259, make a case for a near miss, because of rudder damage from a high explosive bomb.

- ^ Marc Mitscher, commanding Hornet, would two years later issue the same order as the carrier force commander under similar circumstances during the Battle of the Philippine Sea.

- ^ Thanks in part to the slow speed of the Fairey Swordfish. Stephen, Martin. Sea Battles in Close-up: World War 2 (Shepperton, Surrey: Ian Allan, 1988), Volume 1, p.34.

- ^ Japanese casualty figures for the battle were compiled by Sawaichi Hisae for her book Midowei Kaisen: Kiroku p. 550: the list was compiled from Japanese prefectural records and is the most accurate to date.[4]

- ^ Because pre-war Japan was less mechanized than America, the highly trained aircraft mechanics, fitters and technicians lost at Midway were all but impossible to replace and train to a similar level of efficiency.[118]

- ^ Shinano, commissioned on 19 November 1944, was only the fourth fleet carrier commissioned by Japan during the war, after Taihō, Unryū, and Amagi.Chesneau (ed.) Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1922–1946 pp. 169–170, 183–184.

Citations

- ^ Parshall & Tully, p. 90-91

- ^ "The Battle of Midway". Office of Naval Intelligence. http://ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/USN-CN-Midway/USN-CN-Midway-13.html#our.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p.524.

- ^ a b Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.114, 365, 377–380, 476.

- ^ "Battle of Midway: June 4–7,1942". Naval History & Heritage Command. 27 April 2005. http://www.history.navy.mil/faqs/faq81-1.htm. Retrieved 20 February 2009. "...considered the decisive battle of the war in the Pacific."

- ^ Dull, Paul S. Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941–1945. US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-219-9. "Midway was indeed "the" decisive battle of the war in the Pacific.", p. 166

- ^ "A Brief History of Aircraft Carriers: Battle of Midway". U.S. Navy. 2007. Archived from the original on 12 June 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070612040835/http://www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/ships/carriers/midway.html. Retrieved 12 June 2007.

- ^ a b U.S. Naval War College Analysis, p.1; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.416–430.

- ^ Keegan, John. "The Second World War." New York: Penguin, 2005. (275)

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p. 33; Peattie & Evans, Kaigun.[page needed]

- ^ H.P. Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin; Lundstrom, First South Pacific Campaign; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 19–38.

- ^ Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin[page needed]

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 416–419.

- ^ Prange, Miracle at Midway, pp.13–15, 21–23; Willmott, The Barrier and the Javelin, pp. 39–49; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 22–38.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p. 33; Prange, Miracle at Midway, p. 23.

- ^ Prange, Miracle at Midway, pp. 22–26.

- ^ Parshall & Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Parshall & Tully, Shattered Sword, p. 33.

- ^ Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin, pp. 66–67; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 33–34.

- ^ "After the Battle of Midway". Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge. http://www.fws.gov/midway/postwar.html.

- ^ Prange, Miracle at Midway, pp. 375–379, Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin, pp. 110–117; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p. 52.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p. 53, derived from Japanese War History Series (Senshi Sōshō), Volume 43 ('Midowei Kaisen'), p. 118.

- ^ a b Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 51, 55.

- ^ a b Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 43–45, derived from Senshi Sōshō, p. 196.

- ^ Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin.

- ^ a b Lord, Incredible Victory; Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin; Layton, And I Was There: Pearl Harbor and Midway—Breaking the Secrets.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 43–45, derived from Senshi Sōshō, pp. 119–121.

- ^ Prange, Miracle at Midway, pp. 80–81; Cressman et al., A Glorious Page in Our History, p. 37.

- ^ Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin, p.337.

- ^ Cressman et al., A Glorious Page in Our History, pp.37–45; Lord, Incredible Victory, pp.37–39.

- ^ Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin, p.338.

- ^ Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin; p.337–40?

- ^ Lord, Incredible Victory, p.39; Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin, p.340.

- ^ a b Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin, p.101.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 65–67.

- ^ Parshall and Tully Shattered Sword p.89.

- ^ Parshall and Tully Shattered Sword pp. 89–91.

- ^ Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin, p. 351; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Lord, Incredible Victory, pp. 37–39; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p. 99; Holmes, Double-Edged Secrets.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 102–104; Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin.

- ^ Isom, Midway Inquest: Why the Japanese Lost the Battle of Midway, pp.95–99

- ^ Smith The Emperor's Codes p.134

- ^ "AF Is Short of Water". The Battle of Midway. Historical Publications. http://www.nsa.gov/about/cryptologic_heritage/center_crypt_history/publications/battle_midway.shtml. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ^ Smith The Emperor's Codes pp. 138–141

- ^ Holmes, Double-Edged Secrets; Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin.

- ^ a b Admiral Nimitz's CinCPac report of the battle. From Hyperwar. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- ^ a b Interrogation of: Captain TOYAMA, Yasumi, IJN; Chief of Staff Second Destroyer Squadron, flagship Jintsu (CL), at MIDWAY USSBS From Hyperwar. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 107–112, 132–133.

- ^ Willmott, Barrier.

- ^ Stephen, Martin. Sea Battles in Close-up: World War Two (Shepperton, Surrey: Ian Allan, 1988), Volume 1, pp.166 & 167.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 200–204.

- ^ Lord, Incredible Victory, p. 110; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p. 149.

- ^ Prange, Miracle at Midway, pp. 207–212; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 149–152.

- ^ Parshall and Tully Shattered Sword p.182

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.130–132.

- ^ Lord, Walter. Incredible Victory; Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin; Fuchida & Okumiya, Midway

- ^ Isom, Midway Inquest: Why the Japanese Lost the Battle of Midway, pp.129–139

- ^ Prange, Miracle at Midway, pp.216–217; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.159–161 & 183.

- ^ Bicheno, Hugh. Midway (London: Orion Publishing Group, 2001), p.134.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.165–170.

- ^ Fuchida and Okumiya, Midway; Willmott, Barrier & the Javelin.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p. 231, derived from Senshi Sōshō, pp. 372–378.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.121–124.

- ^ Prange, Miracle at Midway, p.233.

- ^ Bicheno, p.163.

- ^ Prange, Miracle at Midway, pp.217–218 & 372–373; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.170–173.

- ^ Prange, Miracle at Midway, pp.231–237; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.170–173; Willmott, Barrier & the Javelin; Fuchida & Okumiya, Midway.

- ^ Willmott, Barrier & the Javelin; Fuchida & Okumiya, Midway.

- ^ 1942 – Battle of Midway

- ^ a b Cressman et al., A Glorious Page in Our History, pp. 84–89; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 215–216; 226–227; Buehl, The Quiet Warrior (1987), p. 494ff.

- ^ a b Battle of Midway (pg 2)

- ^ Mrazek, Robert, "A Dawn Like Thunder", testimony from surviving pilots

- ^ Cressman et al., A Glorious Page in Our History, pp.91–94.

- ^ Blair, Silent Victory, p.238.

- ^ Crenshaw Jr., Russell S. ‘’The Battle of Tassafaronga’’, p.158.

- ^ a b Battle of Midway (pg 3)

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 215–216; 226–227.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Bicheno, Midway, p.62.

- ^ "IJN KIRISHIMA: Tabular Record of Movement". Senkan!. combinedfleet.com. 2006. http://www.combinedfleet.com/Kirishima.html. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ^ Tillman (1976) pp.69–73

- ^ "Accounts – C. Wade McClusky". cv6.org. http://www.cv6.org/company/accounts/wmcclusky/cv6.org.[dead link]

- ^ Prange, Miracle at Midway, pp. 259–261, 267–269; Cressman et al., A Glorious Page in Our History, pp. 96–97; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 215–216; 226–227.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p. 250.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.330–353.

- ^ Ballard, Robert D. and Archbold, Rick. Return to Midway. Madison Press Books: Toronto ISBN 0-7922-7500-4

- ^ Parshall and Tully Shattered Sword, p. 318.

- ^ Parshall and Tully Shattered Sword, p. 323.

- ^ Parshall and Tully Shattered Sword, pp. 328–329.

- ^ Potter & Nimitz 1960 p.682

- ^ Parshall and Tully Shattered Sword, pp. 382–383.

- ^ a b Prange, Miracle at Midway, p. 320; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p. 345.

- ^ Blair, Silent Victory, chart p.240.

- ^ Blair, Silent Victory, pp.246–7.

- ^ Blair, Silent Victory, pp.246–7; Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin.

- ^ Allen, Thomas B. (April 1999). "Return to the Battle of MIDWAY". National Geographic, Journal of the National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C. 195 (4): 80–103 (p.89). ISSN: 0027-9358. http://www.nationalgeographic.com/midway.

- ^ Parshall and Tully Shattered Sword, p. 176.

- ^ Parshall and Tully Shattered Sword, pp. 374–375, 383.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p. 476.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.378, 380.

- ^ a b Blair, Silent Victory, p.247.

- ^ Morison, Coral Sea, Midway and Submarine Actions: May 1942 – August 1942. (History of United States Naval Operations in World War II), Volume IV, p. 142

- ^ Chūichi Nagumo (June 1942). "CINC First Air Fleet Detailed Battle Report no. 6". http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/Japan/IJN/rep/Midway/Nagumo/.

- ^ Herbert Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, 2001, p. 449

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p.386.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.386–387.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p.388.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.388–389.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.390–391.

- ^ Robert E. Barde, "Midway: Tarnished Victory", Military Affairs, v. 47, no. 4 (December 1983), pp. 188–192.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p. 563.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, pp. 320 & 566.

- ^ Dull, p.166; Prange, p.395.

- ^ Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin, pp.522–523; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.416–430.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 422–423.

- ^ Dull, The Imperial Japanese Navy: A Battle History, p.166; Willmott, The Barrier and the Javelin, pp.519–523; Prange, Miracle at Midway p.395.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p. 432.

- ^ a b Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p.417.

- ^ a b Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp.416–417, 432.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, p. 421.

- ^ "Why Japan Really Lost The War – War Production". combinedfleet.com. http://www.combinedfleet.com/economic.htm.

- ^ Hakim, A History of Us: War, Peace and all that Jazz

- ^ "Titanic explorer finds Yorktown". CNN. 4 June 1998. http://www.cnn.com/TECH/science/9806/04/yorktown.found/index.html. Retrieved 1 July 2007.

- ^ Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, pp. 491–493.

Bibliography

- Barde, Robert E. "Midway: Tarnished Victory", Military Affairs, v. 47, no. 4 (December 1983)

- Bergerund, Eric M. (2000). Fire in the Sky: The Air War in the South Pacific. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. p. 752. ISBN 978-0-8133-2985-7.

- Bicheno, Hugh. Midway. London: Orion Publishing Group, 2001 (reprints Cassell 2001 edition)

- Blair Jr., Clay (1975). Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott. p. 1072.

- Buell, Thomas B. (1987). The Quiet Warrior: a Biography of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. p. 518. ISBN 0-87021-562-0.

- Cressman, Robert J.; et.al. (1990). "A Glorious page in our history", Adm. Chester Nimitz, 1942: the Battle of Midway, 4–6 June 1942. Missoula, Mont.: Pictorial Histories Pub. Co.. ISBN 0-929521-40-4.

- Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1941–1945). US Naval Institute Press.

- Evans, David; Peattie, Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

- Fuchida, Mitsuo; Masatake Okumiya (1955). Midway: The Battle that Doomed Japan, the Japanese Navy's Story. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-372-5. A Japanese account; numerous assertions in this work have been challenged by more recent sources.

- Stephan, John J. (1984). Hawaii Under the Rising Sun: Japan's Plans for Conquest after Pearl Harbor. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2550-0.

- Bix, Herbert P. (2001). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. New York: Perennial / HarperCollinsPublishers. ISBN 0-06-019314-X.

- Holmes, W. (1979). Double-Edged Secrets: U.S. Naval Intelligence Operations in the Pacific During World War II (Bluejacket Books). Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-324-9.

- Hakim, Joy (1995). A History of Us: War, Peace and all that Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509514-6.

- Layton, Rear Admiral Edwin T. (1985). And I Was There: Pearl Harbor and Midway, Konecky and Konecky.

- Lord, Walter (1967). Incredible Victory. Burford. ISBN 1-58080-059-9. Focuses primarily on the human experience of the battle.

- Lundstrom, John B. (2005 (new edition)). The First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat from Pearl Harbor to Midway. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-471-X.

- Parillo, Mark. Japanese Merchant Marine in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute Press, 1993.

- Parshall, Jonathan; Tully, Anthony (2005). Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books. ISBN 1-57488-923-0. Uses recently translated Japanese sources.

- Peattie, Mark R.. Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power, 1909–1941. US Naval Institute Press. p. 392. ISBN 1-59114-664-X.

- Potter, E. B. and Nimitz, Chester W. (1960). Sea Power. Prentice-Hall.

- Prange, Gordon W.; Goldstein, Donald M., and Dillon, Katherine V. (1982). Miracle at Midway. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-050672-8. The standard academic history of the battle based on massive research into American and Japanese sources.

- Smith, Michael (2000). The Emperor's Codes: Bletchley Park and the breaking of Japan's secret ciphers, Bantam Press, ISBN 0-593-04642-0. Chapter 11: "Midway: The battle that turned the tide"

- Willmott, H.P. (1983). The Barrier and the Javelin: Japanese and Allied Strategies, February to June 1942. United States Naval Institute Press. p. 616. ISBN 1-59114-949-5. Broad-scale history of the naval war with detailed accounts of order of battle and dispositions.

Further reading

Books

- Bess, Michael (2006). Choices Under Fire: Moral Dimensions of World War II. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-307-26365-7.

- Chesneau, Roger (ed.) (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Ewing, Steve (2004). Thach Weave: The Life of Jimmie Thach. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-248-2.

- Hanson, Victor D. (2001). Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-50052-1.

- Hara, Tameichi (1961). Japanese Destroyer Captain. ISBN 0-345-27894-1. First-hand account by Japanese captain, often inaccurate.

- Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. Scribner. ISBN 0-684-83130-9. Significant section on Midway

- Kernan, Alvin (2005). The Unknown Battle of Midway. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10989-X. An account of the blunders that led to the near total destruction of the American torpedo squadrons, and of what the author calls a cover-up by naval officers after the battle.

- Lundstrom, John B. (2005 (New edition)). First Team And the Guadalcanal Campaign: Naval Fighter Combat from August to November 1942. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-472-8.

- Morison, Samuel E. (1949). Coral Sea, Midway and Submarine Actions: May 1942 – August 1942. (History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 4) official U.S. history.

- Smith, Douglas V. (2006). Carrier Battles: Command Decision in Harm's Way. U.S. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-794-8.

- Smith, Peter C. (2007). Midway Dauntless Victory; Fresh perspectives on America's Seminal Naval Victory of 1942. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 1-84415-583-8. Detailed study of battle, from planning to the effects on World War II

- Stille, Mark (2007). USN Carriers vs IJN Carriers: The Pacific 1942. New York: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-248-6.

- Tillman, Barrett (1976). The Dauntless Dive-bomber of World War Two. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-569-8.

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. (1994). A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge U P.

- Willmott, H.P.. The Second World War in the Far East (Smithsonian History of Warfare). Smithsonian Books. p. 240. ISBN 1-58834-192-5.

Articles

- The Course to Midway Turning Point in the Pacific, Comprehensive historic overview

Historic documents

- The Japanese Story of the Battle of Midway, prepared by U.S. Naval Intelligence from captured Japanese documents

- Battle of Midway Movie (1942) – U.S. Navy propaganda film directed by John Ford.

- Victory At Sea: Midway Is East (1952) – Episode 4 from a 26-episode series about naval combat during World War II.

- The Battle of Midway (1942) at the Internet Movie Database

- The Course to Midway Turning Point in the Pacific, Comprehensive historic overview created by Bill Spencer

- Naval Historical Center Midway Page

- "The Japanese Story of the Battle of Midway" – ONI Review – Vol. 2, No. 5 (May 1947)

Miscellaneous

- Cook, Theodore F., Jr. (2000). "Our Midway Disaster". In Robert Cowley (ed.). What if?. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-75183-3. Counterfactual fiction has the Japanese winning.

- Schlesinger, James R., "Midway in Retrospect: The Still Under-Appreciated Victory", 5 June 2005. (An analysis by former Secretary of Defense Schlesinger.) Available from the Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy.

- WW2DB: The Battle of Midway

- After Midway: The Fates of the U.S. and Japanese Warships by Bryan J. Dickerson

- Animated History of The Battle of Midway

- Midway Chronology 1

- Midway Chronology 2

World War II Participants Timeline - Burma

- Changsha (1942)

- Coral Sea

- Gazala

- Midway

- Blue

- Stalingrad

- Dieppe

- El Alamein

- Torch

- Guadalcanal

Aspects GeneralWar crimes- German and Wehrmacht war crimes

- The Holocaust

- Italian war crimes

- Japanese war crimes

- Unit 731

- Allied war crimes

- Soviet war crimes

- United States war crimes

- German military brothels

- Camp brothels

- Rape during the occupation of Japan

- Comfort women

- Rape of Nanking

- Rape during the occupation of Germany

- Nazi crimes against Soviet POWs

- Italian prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

- Japanese prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

- Japanese prisoners of war in World War II

- German prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

- Finnish prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

- Polish prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

- Romanian prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

- German prisoners of war in the United States

Categories:- Battle of Midway

- History of Midway Atoll

- Asia and the Pacific 1941-42

- Battles involving Hawaii

- History of cryptography

- Imperial Japanese Navy

- Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service

- Naval aviation operations and battles

- Naval battles and operations of World War II

- Naval battles of World War II involving Japan

- Naval battles of World War II involving the United States

- Pacific Ocean theater of World War II

- United States Marine Corps in World War II

- United States naval aviation

- Pacific War battlefields

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.