- History of Croatia

-

History of Croatia

This article is part of a seriesEarly history Prehistoric Croatia Origins of the Croats White Croatia Medieval history Littoral Croatia · Pannonian Croatia · Pagania · Zachlumia · Travunia Kingdom of Croatia March of Istria Republic of Poljica Republic of Dubrovnik Kingdom of Bosnia Habsburg Empire Kingdom of Croatia Croatian Military Frontier Illyrian Provinces · Kingdom of Illyria Kingdom of Slavonia Kingdom of Dalmatia Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs Yugoslavia Kingdom of Yugoslavia

(Banovina of Croatia)World War II

Independent State of Croatia

Federal State of CroatiaSocialist Republic of Croatia Contemporary Croatia War of independence Republic of Croatia

Croatia Portal

Croatia first appeared as a duchy in the 7th century and then as a kingdom in the 10th century. From the 12th century it remained a distinct state with its ruler (ban) and parliament, but it obeyed the kings and emperors of various neighboring powers, primarily Hungary and Austria. The period from the 15th to the 17th centuries was marked by bitter struggles with the Ottoman Empire. After being incorporated in Yugoslavia for most of the 20th century, Croatia regained independence in 1991.

Croatian lands before the Croats (until 7th c.)

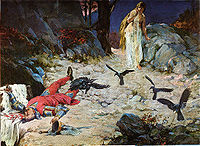

See also: Prehistoric Croatia, Theories on the origin of Croats, and White Croatia Oton Iveković, The Croats arrival at the Adriatic Sea

Oton Iveković, The Croats arrival at the Adriatic Sea

The area known as Croatia today was inhabited throughout the prehistoric period. Fossils of Neanderthals dating to the middle Palaeolithic period have been unearthed in northern Croatia, with the most famous and the best presented site in Krapina.[1] Remnants of several Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures were found in all regions of the country.[2] The largest proportion of the sites is in the northern Croatia river valleys, and the most significant cultures whose presence was discovered include Starčevo, Vučedol and Baden cultures.[3][4] The Iron Age left traces of the early Illyrian Hallstatt culture and the Celtic La Tène culture.[5]

Much later, the region was settled by Liburnians and Illyrians, while the first Greek colonies were established on the Vis and Hvar.[6] In 9 AD the territory of today's Croatia became part of the Roman Empire and subsequently to the Western Roman Empire. The empire organized the provinces of Pannonia and Dalmatia in the area, whose parts passed to the Huns, the Ostrogoths and the Byzantium after downfall of the empire. Emperor Diocletian built a large palace in Split when he retired in AD 305.[7] During the 5th century, one of the last Emperors of the Western Roman Empire, Julius Nepos, ruled his small empire from the palace.[8] The period ends with Avar and Croat invasions in the first half of the 7th century and destruction of almost all Roman towns. Roman survivors retreated to more favourable sites on the coast, islands and mountains. The city of Dubrovnik was founded by such survivors from Epidaurum.[9]

Medieval Croatian states (until 925)

Main articles: Principality of Littoral Croatia, Principality of Pannonian Croatia, Pagania, and ZachlumiaAccording to the work De Administrando Imperio written by the 10th-century Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII, the Croats had arrived in what is today Croatia in the early 7th century, however that claim is disputed and competing hypotheses date the event between the 6th and the 9th centuries.[10] Eventually two dukedoms were formed—Duchy of Pannonia and Duchy of Dalmatia, ruled by Ljudevit Posavski and Borna, as attested by chronicles of Einhard starting in the year 818. The record represents the first document of Croatian realms, vassal states of Francia at the time.[11] The Frankish overlordship ended during the reign of Mislav two decades later.[12] According to the Constantine VII christianization of Croats began in the 7th century, but the claim is disputed and generally christianization is associated with the 9th century.[13] The first native Croatian ruler recognised by the Pope was duke Branimir, whom Pope John VIII referred to as Dux Croatorum ("Duke of Croats") in 879.[14]

Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102)

Main article: Kingdom of Croatia (medieval)Tomislav was the first ruler of Croatia who was styled a king in a letter from the Pope John X, dating kingdom of Croatia to year 925. Tomislav defeated Hungarian and Bulgarian invasions, spreading the influence of Croatian kings.[15] The medieval Croatian kingdom reached its peak in the 11th century during the reigns of Petar Krešimir IV (1058–1074) and Dmitar Zvonimir (1075–1089).[16] When Stjepan II died in 1091 ending the Trpimirović dynasty, Ladislaus I of Hungary claimed Croatian crown. Opposition to the claim led to a war and personal union of Croatia and Hungary in 1102, ruled by Coloman.[17]

Personal union with Hungary (1102–1918)

Death of the Last Croatian King, by Oton Iveković

Death of the Last Croatian King, by Oton Iveković

The consequences of the change to the Hungarian king included the introduction of feudalism and the rise of the native noble families such as Frankopan and Šubić. The later kings sought to restore some of their previously lost influence by giving certain privileges to the towns. For the next four centuries, the Kingdom of Croatia was ruled by the Sabor (parliament) and a Ban (viceroy) appointed by the king.[18]

The princes of Bribir from the Šubić family became particularly influential, asserting control over large parts of Dalmatia, Slavonia and Bosnia. Later, however, the Angevins intervened and restored royal power. The period saw rise of native nobility such as the Frankopans and the Šubićs to prominence and ultimately numerous Bans from the two families.[19]

Separate coronation as King of Croatia was gradually allowed to fall into abeyance and last crowned king is Charles Robert in 1301 after which Croatia contented herself with a separate diploma inaugurale. The reign of Louis the Great (1342–1382) is considered the golden age of Croatian medieval history.[20] Sigismund of Luxemburg also sold the whole of Dalmatia to Venice in 1409. The period saw increasing threat of Ottoman conquest and struggle against the Republic of Venice for control of coastal areas. The Venetians gained control over most of Dalmatia by 1428, with exception of the city-state of Dubrovnik which became independent.[21] In 1490 the estates of Croatia declined to recognize Vladislaus II until he had taken oath to respect their liberties, and insisted upon his erasing from the diploma certain phrases which seemed to reduce Croatia to the rank of a mere province. The dispute was solved in 1492 [22]

As the Turkish incursion into Europe started, Croatia once again became a border area. The Croats fought an increasing number of battles and gradually lost increasing swaths of territory to the Ottoman Empire. Ottoman conquests led to the 1493 Battle of Krbava field and 1526 Battle of Mohács, both ending in decisive Ottoman victories. King Louis II died at Mohács, and in 1527, and the Hungarian parliament elected János Szapolyai as the new king of Hungary. Another Hungarian parliament elected Ferdinand Habsburg as King of Hungary. On the other side, the Parliament on Cetin chose Ferdinand I of the House of Habsburg as new ruler of Croatia, under the condition that he provide protection to Croatia against the Ottoman Empire while respecting its political rights.[18][21][22] A few years later both crown would be again united in Habsburgs hands and the union would be restored. The Ottoman Empire further expanded in the 16th century to include most of Slavonia, western Bosnia and Lika.

Later in the same century, Croatia was so weak that its parliament authorized Ferdinand Habsburg to carve out large areas of Croatia and Slavonia adjacent to the Ottoman Empire for the creation of the Military Frontier (Vojna Krajina, German Militaergrenze) which would be ruled directly from Vienna's military headquarters.[23] The area became rather deserted and was subsequently settled by Serbs, Vlachs, Croats and Germans and others. As a result of their compulsory military service to the Habsburg Empire during conflict with the Ottoman Empire, the population in the Military Frontier was free of serfdom and enjoyed much political autonomy, unlike the population living in the parts ruled by Hungary.

After the Bihać fort finally fell in 1592, only small parts of Croatia remained unconquered. The Ottoman army was successfully repelled for the first time on the territory of Croatia following the battle of Sisak in 1593. The lost territory was mostly restored, except for large parts of today's Bosnia and Herzegovina.

By the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire was driven out of Hungary, and Austria brought the empire under central control. Empress Maria Theresa of Austria was supported by the Croatians in the War of Austrian Succession of 1741–1748 and subsequently made significant contributions to Croatian matters.

With the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797, its possessions in eastern Adriatic became subject to a dispute between France and Austria. The Habsburgs eventually secured them (by 1815) and Dalmatia and Istria became part of the empire, though they were in Cisleithania while Croatia and Slavonia were under Hungary.

Croatian romantic nationalism emerged in mid-19th century to counteract the apparent Germanization and Magyarization of Croatia. The Illyrian movement attracted a number of influential figures from 1830s on, and produced some important advances in the Croatian language and culture.

In the Revolutions of 1848 Croatia, driven by fear of Magyar nationalism, supported the Habsburg court against Hungarian revolutionary forces. However, despite the contributions of its ban Jelačić in quenching the Hungarian war of independence, Croatia, not treated any more favourably by Vienna than the Hungarians themselves, lost its domestic autonomy. In 1867 the Dual Monarchy was created; Croatian autonomy was restored in 1868 with the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement which was comparatively favourable for the Croatians, but still problematic because of issues such as the unresolved status of Rijeka.

Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918–1941)

Main article: Croatia in the first Yugoslavia Coat of arms of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

Coat of arms of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

Shortly before the end of the First World War in 1918, the Croatian Parliament severed relations with Austria-Hungary as the Entente armies defeated those of the Habsburgs. Croatia and Slavonia became a part of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs composed out of all Southern Slavic territories of the now former Austro-Hungarian Monarchy with a transitional government headed in Zagreb. Although the state inherited much of Austro-Hungary's military arsenal, including the entire fleet, the Kingdom of Italy moved rapidly to annex the state's most western territories, promised to her by the Treaty of London of 1915. An Italian Army eventually took Istria, started to annex the Adriatic islands one by one, and even landed in Zadar. After Srijem left Croatia and Slavonia and joined Serbia together with Vojvodina, which was shortly followed by a referendum to join Bosnia and Herzegovina to Serbia, the People's Council (Narodno vijeće) of the state, guided by what was by that time a half a century long tradition of pan-Slavism and without sanction of the Croatian sabor, joined the Kingdom of Serbia into the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The territory of Croatia largely comprised the territories of the Sava and Littoral Banates.

The Kingdom underwent a crucial change in 1921 to the dismay of Croatia's largest political party, the Croatian Peasant Party (Hrvatska seljačka stranka). The new constitution abolished the historical/political entities, including Croatia and Slavonia, centralizing authority in the capital of Belgrade. The Croatian Peasant Party boycotted the government of the Serbian People's Radical Party throughout the period, except for a brief interlude between 1925 and 1927, when external Italian expansionism was at hand with her allies, Albania, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria that threatened Yugoslavia as a whole.

In the early 1920s the Yugoslav government of Serbian prime minister Nikola Pasic used police pressure over voters and ethnic minorities, confiscation of opposition pamphlets[24] and other measures of election rigging to keep the opposition, and mainly the Croatian Peasant Party and its allies in minority in Yugoslav parliament.[25] Pasic believed that Yugoslavia should be as centralized as possible, creating in place of distinct regional governments and identities a Greater Serbian national concept of concentrated power in the hands of Belgrade.[26]

During a Parliament session in 1928, the Croatian Peasant Party's leader Stjepan Radić was mortally wounded by Puniša Račić, a deputy of the Serbian Radical People's Party, which caused further upsets among the Croatian elite. In 1929, King Aleksandar proclaimed a dictatorship and imposed a new constitution which, among other things, renamed the country the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Political parties were banned from the start and the royal dictatorship took on an increasingly harsh character. Vladko Maček, who had succeeded Radić as leader of the Croatian Peasant Party, the largest political party in Croatia, was imprisoned, and members of a newly emerging insurgent movement, the Ustaše, went into exile. According to the British historian Misha Glenny the murder in March 1929 of Toni Schlegel, editor of a pro-Yugoslavian newspaper Novosti, brought a "furious response" from the regime. In Lika and west Herzegovina in particular, which he described as "hotbeds of Croatian separatism," he wrote that the majority-Serb police acted "with no restraining authority whatsoever."[27] And in the words of a prominent Croatian writer, Shlegel's death became the pretext for terror in all forms. Politics was soon "indistinguishable from gangsterism."[28] Even in this oppressive climate, few rallied to the Ustaša cause and the movement was never able to organise within Croatia. But its leaders did manage to convince the Communist Party that it was a progressive movement. The party's newspaper Proleter (December 1932) stated: "[We] salute the Ustaša movement of the peasants of Lika and Dalmatia and fully support them."

In 1934, King Aleksandar was assassinated abroad, in Marseille, by a coalition of the Ustaše and a similarly radical movement, the Macedonian pro-Bulgarian VMORO. The Serbian-Croatian Cvetković-Maček government that came to power, distanced Yugoslavia's former allies of France and the United Kingdom, and moved closer to Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany in the period of 1935–1941. A national Banovina of Croatia was created in 1939 out of the two Banates, as well as parts of the Zeta, Vrbas, Drina and Danube Banates. It had a reconstructed Croatian Parliament which would choose a Croatian Ban and Viceban. This Croatia included a part of Bosnia (region), most of Herzegovina and the city of Dubrovnik and the surroundings.

World War II (1941–1945)

Main article: Independent State of CroatiaThe Axis occupation of Yugoslavia in 1941 allowed the Croatian radical right Ustaše to come into power, forming the "Independent State of Croatia", led by Ante Pavelić, who assumed the role of Poglavnik ("Head-man") Nezavisne Drzave Hrvatske ("Leader of the Independent State of Croatia"). Following the pattern of other fascist regimes in Europe, the Ustashi enacted racial laws, formed eight concentration camps targeting minority Serbs, Romas and Jewish populations, as well as Croatian partisans. The biggest concentration camp was Jasenovac in Croatia. The NDH had a program, formulated by Mile Budak, to purge Croatia of Serbs, by "killing one third, expelling the other third and assimilating the remaining third". The first part of this program began during WWII with a planned genocide in Jasenovac and other locations in the NDH[29] The main targets for persecution, however, were the Serbs, approximately 330,000 of Serbs were killed.[30][31]

The anti-fascist communist-led Partisan movement, based on pan-Yugoslav ideology, emerged in early 1941, under the command of Croatian-born Josip Broz Tito, spreading quickly into many parts of Yugoslavia. The 1st Sisak Partisan Detachment, often hailed as the first armed anti-fascist resistance unit in occupied Europe, was formed in Croatia, in the Brezovica forest near the town of Sisak. As the movement began to gain popularity, the Partisans gained strength from Croats, Bosniaks, Serbs, Slovenes, and Macedonians who believed in a unified, but federal, Yugoslav state.

By 1943, the Partisan resistance movement had gained the upper hand, against the odds, and in 1945, with help from the Soviet Red Army (passing only through small parts such as Vojvodina), expelled the Axis forces and local supporters. The ZAVNOH, state anti-fascist council of people's liberation of Croatia, functioned since 1944 and formed an interim civil government. NDH's ministers of War and Internal Security Mladen Lorković and Ante Vokić tried to switch to Allied side. Pavelić was in the beginning supporting them but when he found that he would need to leave his position he imprisoned them in Lepoglava prison where they were executed.

Following the defeat of the Independent State of Croatia at the end of the war a large number of Ustaše, and civilians supporting them (ranging from sympathisers, young conscripts, anti-communists, and ordinary serfs who were motivated by Partisan atrocities) attempted to flee in the direction of Austria hoping to surrender to British forces and to be given refuge. They were instead interned by British forces and then returned to the Partisans. A large number of these persons were killed in what has come to be called the Bleiburg massacre.

Communist Yugoslavia (1945–1991)

Coat of arms of the Socialist Republic of Croatia

Coat of arms of the Socialist Republic of Croatia Main article: Socialist Republic of Croatia

Main article: Socialist Republic of CroatiaTito Dictatorship (1945-1980)

Croatia was a Socialist Republic part of a six-part Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia. Under the new communist system, privately owned factories and estates were nationalized, and the economy was based on a type of planned market socialism. The country underwent a rebuilding process, recovered from World War II, went through industrialization and started developing tourism.

The country's socialist system also provided free apartments from big companies, which with the workers' self-management investments paid for the living spaces. From 1963, the citizens of Yugoslavia were allowed to travel to almost any country because of the neutral politics. No visas were required to travel to eastern or western countries, capitalist or communist nations.[32] Such free travel was unheard of at the time in the Eastern Bloc countries, and in some western countries as well (e.g. Spain or Portugal, both dictatorships at the time). This proved to be very helpful for Croatia's inhabitants who found working in foreign countries more financially rewarding. Upon retirement, a popular plan was to return to live in Croatia (then Yugoslavia) to buy a more expensive property.

In Yugoslavia, the people of Croatia were guaranteed free healthcare, free dental care, and secure pensions. The older generation found this very comforting as pensions would sometimes exceed their former paychecks. Free trade and travel within the country also helped Croatian industries that imported and exported throughout all the former republics. Students and military personnel were encouraged to visit other republics to learn more about the country, and all levels of education, especially secondary education and higher education, were gratis. In reality the housing was inferior with poor heat and plumbing, the medical care often lacking even in availability of antibiotics, schools were propaganda machines and travel was a necessity to provide the country with hard currency. The propagandists who want people to believe "neutral policies" equalized Serbs and Croats severely restricted free speech and did not protect citizens from ethnic attacks. Membership in the party was as much a prerequisite for admission to colleges and for government jobs as in the Soviet Union under Stalin or Kruchev. Private sector businesses did not grow as the taxes on private enterprise were often prohibitive. Inexperienced management sometimes ruled policy and controlled decisions by brute force. Strikes were forbidden, Owner/Managers were not permitted to make changes in decisions which would impact their productivity or profit.

The economy developed into a type of socialism called samoupravljanje (self-management), in which workers controlled socially-owned enterprises. This kind of market socialism created significantly better economic conditions than in the Eastern Bloc countries. Croatia went through intensive industrialization in the 1960s and 1970s with industrial output increasing several-fold and with Zagreb surpassing Belgrade for the amount of industry. Factories and other organizations were often named after Partisans who were declared national heroes. This practice also spread to street names, names of parks and buildings and some more trivial features.

Before World War II, Croatia's industry was not significant, with the vast majority of the people employed in agriculture. By 1991 the country was completely transformed into a modern industrialized state. By the same time, the Croatian Adriatic coast had taken shape as an internationally popular tourist destination, all coastal republics (but mostly SR Croatia) profited greatly from this, as tourist numbers reached levels still unsurpassed in modern Croatia. The government brought unprecedented economic and industrial growth, high levels of social security and a very low crime rate. The country completely recovered from WW2 and achieved a very high GDP and economic growth rate, significantly higher than the present-day Republic.

The constitution of 1963 balanced the power in the country between the Croats and the Serbs, and alleviated the fact that the Croats were again in a minority. Trends after 1965 (like the fall of OZNA and UDBA chief Aleksandar Ranković from power in 1966),[33] however, led to the Croatian Spring of 1970–71, when students in Zagreb organized demonstrations for greater civil liberties and greater Croatian autonomy. The regime stifled the public protest and incarcerated the leaders, but this led to the ratification of a new Constitution in 1974, giving more rights to the individual republics.

At that time, radical Ustaše cells of Croatian émigrés in Western Europe[34] planned and guerilla acts inside Yugoslavia, but they were largely countered.[35]

Towards Independence (1980-1991)

In 1980, after Tito's death, economic, political, and religious difficulties started to mount and the federal government began to crumble. The crisis in Kosovo and, in 1986, the emergence of Slobodan Milošević in Serbia provoked a very negative reaction in Croatia and Slovenia; politicians from both republics feared that his motives would threaten their republics' autonomy. With the climate of change throughout Eastern Europe during the 1980s, the communist hegemony was challenged (at the same time, the Milošević government began to gradually concentrate Yugoslav power in Serbia and calls for free multi-party elections were becoming louder. In June 1989 the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) was founded by Croatian nationalist dissidents led by Franjo Tuđman a former fighter in Tito's Partisan movement and JNA General. At this time Yugoslavia was still a one-party state and open manifestations of Croatian nationalism were dangerous so new party was founded in an almost conspiratorial manner. It was only on 13 Dec 1989 that the governing League of Communists of Croatia agreed to legalize opposition political parties and hold free elections in the spring of 1990.[36]

On 23 Jan 1990 at its 14th Congress the Communist League of Yugoslavia voted to remove its monopoly on political power, but the same day effectively ceased to exist as a national party when the League of Communists of Slovenia walked out after Serbia`s Slobodan Milošević blocked all their reformist proposals - the League of Communists of Croatia walked out soon after. On 22 April and 7 May 1990, the first free multi-party elections were held in Croatia. Franjo Tuđman's Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) won by a relatively slim margin against Ivica Račan's reformed communist Party of Democratic Change (SDP). However, Croatia's first-past-the-post election system enabled Tuđman to form the government relatively independently. The HDZ's intentions were to secure independence for Croatia, contrary to the wishes of a part of the ethnic Serbs in the republic, and federal and national politicians in Belgrade. The excessively polarized climate soon escalated into complete estrangement between the two nations and spiralled into sectarian violence.

On July 25, 1990, a Serbian Assembly was established in Srb, north of Knin, as the political representation of the Serbian people in Croatia. The Serbian Assembly declared "sovereignty and autonomy of the Serb people in Croatia".[37] Their position was that if Croatia could secede from Yugoslavia, then the Serbs could secede from Croatia. Milan Babić, a dentist from the southern town of Knin, was elected president. The rebel Croatian Serbs established a number of paramilitary militias under the leadership of Milan Martić, the police chief in Knin. On 17 August 1990, the Serbs began what became known as the Log Revolution, where barricades of logs were placed across roads throughout the South as an expression of their secession from Croatia. This effectively cut Croatia in two, separating the coastal region of Dalmatia from the rest of the country. The Croatian government responded to the blockade of roads by sending special police teams in helicopters to the scene, but they were intercepted by SFR Yugoslav Air Force fighter jets and forced to turn back to Zagreb.

The Croatian constitution was passed in December, 1990 categorizing Serbs as a minority group along with other ethnic groups. Babić's administration announced the creation of a Serbian Autonomous Oblast of Krajina (or SAO Krajina) on 21 December 1990. Other Serb-dominated communities in eastern Croatia announced that they would also join SAO Krajina and ceased paying taxes to the Zagreb government.

On Easter Sunday, 31 March 1991, the first fatal clashes occurred when Croatian police from the Croatian Ministry of the Interior (MUP) entered the Plitvice Lakes national park to expel rebel Serb forces. Serb paramilitaries ambushed a bus carrying Croatian police into the national park on the road north of Korenica, sparking a day-long gun battle between the two sides. During the fighting, two people, one Croat and one Serb policeman, were killed. Twenty other people were injured and twenty-nine Krajina Serb paramilitaries and policemen were taken prisoner by Croatian forces.[38][39] Among the prisoners was Goran Hadžić, later to become the President of the Republic of Serbian Krajina.[40]

On 2 May 1991 the Croatian parliament voted to hold a referendum on independence.[41] On 19 May 1991, on an almost 80% turnout, 93.24% voted for independence. Krajina boycotted the referendum. They held their own referendum a week earlier on 12 May 1991 in the territories they controlled and voted to remain in Yugoslavia which the Croatian government did not recognize as valid.

On 25 Jun 1991 the Parliament of Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia. Slovenia declared independence from Yugoslavia on the same day.[42]

Republic of Croatia (1991-Present Day)

Croatian War of Independence (1991–1995)

Clockwise from top left: The central street of Dubrovnik, the Stradun, in ruins during the Siege of Dubrovnik; the damaged Vukovar water tower, a symbol of the early conflict, flying the Croatian tricolour; soldiers of the Croatian Army getting ready to destroy a Serbian tank; the Vukovar Memorial Cemetery; a Serbian T-55 tank destroyed on the road to Drniš

Clockwise from top left: The central street of Dubrovnik, the Stradun, in ruins during the Siege of Dubrovnik; the damaged Vukovar water tower, a symbol of the early conflict, flying the Croatian tricolour; soldiers of the Croatian Army getting ready to destroy a Serbian tank; the Vukovar Memorial Cemetery; a Serbian T-55 tank destroyed on the road to Drniš Main article: Croatian War of Independence

Main article: Croatian War of IndependenceThe civilian population fled the areas of armed conflict en masse: generally speaking, hundreds of thousands of Croats moved away from the Bosnian and Serbian border areas, while thousands of Serbs moved towards it. In many places, masses of civilians were forced out by the Yugoslav National Army (JNA), who consisted mostly of conscripts from Serbia and Montenegro, and irregulars from Serbia, in what became known as ethnic cleansing.

The border city of Vukovar underwent a three month siege — the Battle of Vukovar — during which most of the city was destroyed and a majority of the population was forced to flee. The city fell to the Serbian forces on November 18, 1991 and the Vukovar massacre occurred.

Subsequent UN-sponsored cease-fires followed, and the warring parties mostly entrenched. The Yugoslav People's Army retreated from Croatia into Bosnia and Herzegovina where a new cycle of tensions were escalating: the Bosnian War was to start. During 1992 and 1993, Croatia also handled an estimated 700,000 refugees from Bosnia, mainly Bosnian Muslims.

Armed conflict in Croatia remained intermittent and mostly on a small scale until 1995. In early August, Croatia embarked on Operation Storm, this action, though illegal under the UN[citation needed], would not have been initiated if not for the approval from the United States. The Croatian attack quickly reconquered most of the territories from the Republic of Serbian Krajina authorities, leading to a mass exodus of the Serbian population. An estimated 90,000–350,000 Serbs fled shortly before,[43][44] during and after the operation. As a result of this operation, a few months later the Bosnian war ended with the negotiation of the Dayton Agreement. A peaceful integration of the remaining Serbian-controlled territories in eastern Slavonia was completed in 1998 under UN supervision. The majority of the Serbs who fled from the former Krajina have not returned due to fears of ethnic violence, discrimination and property repossession problems, and the Croatian government has yet to achieve the conditions for full reintegration.[45] According to United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, around 125,000 ethnic Serbs who fled the 1991-1995 conflict are registered as having returned to Croatia, of whom around 55,000 remain permanently.[46]

Tuđman: Peacetime Presidency (1995-1999)

The modern period in Croatian history begins in 1990 with the country's change of political and economic system as well as Declaring independence from Yugoslavia in 1991, and obtaining it in 1992.

Following the end of the war, Franjo Tuđman's government started to lose popularity as it was criticized (among other things) for its involvement in suspicious privatization deals of the early 1990s. In 1995, the opposition surprisingly won in the capital of Zagreb, which led to the Zagreb crisis when Tuđman refused to accept this victory.

Tuđman has been accused that his domestic policy was quite non-democratic. Even during his presidency there were circles in society who claimed that Tuđman's rule was autocratic and that he showed little sensitivity to criticism. In particular, these circles consider that during the Tuđman era civil rights record to the minority Serb population was poor.[47] In 2001 a review from the IPI reported about an increased number of libel law suits that were initiated during Tuđman's mandate.[48]

From an economic view, the Republic of Croatia (as well as the remainder of Yugoslavia) experienced a serious depression. Tuđman initiated the process of privatization and de-nationalization in Croatia, however, this was far from transparent or fully legal. The fact that the new government's legal system was inefficient and slow, as well as the wider context of the Yugoslav wars caused numerous incidents known collectively in Croatia as the "Privatization robbery" (Croatian: "privatizacijska pljačka"). Nepotism was endemic and during this period many influential individuals with the backing of the authorities acquired state-owned property and companies at extremely low prices, afterwards selling them off piecemeal to the highest bidder for much larger sums. This proved very lucrative for the new owners, but in the vast majority of cases this (along with the separation from the previously secured Yugoslav markets) also caused the bankruptcy of the (previously successful) firm, causing the unemployment of thousands of citizens, a problem Croatia still struggles with to this day.

This was all helped, not just by the (allegedly purposeful) inadequacy of legal restrictions, but also by the apparently active support of the new Croatia's authorities, ultimately controlled by Tuđman from his strong presidential position. In the end this shed an increasingly negative light, and cast a shadow on his notable successes as a strategist and wartime statesman. Excluding the mostly rural rebel-occupied areas (the so-called Republic of Serbian Krajina), in the last two years of Tuđman's first tenure the detrimental effects of "wild" and unrestricted capitalism had become strikingly visible, with more than 400,000 unemployed citizens, and a significant drop in the GDP per capita, problems Croatia struggles with to this day.

Croatia became a member of the Council of Europe on November 6, 1996. 1996 and 1997 were a period of post-war recovery and improving economic conditions.

The remaining part of former "Krajina", areas adjacent to FR Yugoslavia, negotiated a peaceful reintegration process with the Croatian Government. The so-called Erdut Agreement made the area a temporary protectorate of the UN Transitional Administration for Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Sirmium. The area was formally re-integrated into Croatia on January 15, 1998.

Changes in the 2000s

Ivo Josipović

Ivo Josipović Main article: Accession of Croatia to the European Union

Main article: Accession of Croatia to the European UnionRačan government (2000-2003)

Tuđman died in 1999 and in the early 2000 parliamentary elections, the nationalist HDZ government was replaced by a center-left coalition, with Ivica Račan as prime minister. At the same time, presidential elections were held which were won by a moderate, Stjepan Mesić.

The new Račan government amended the Constitution, changing the political system from a presidential system to a parliamentary system, transferring most executive presidential powers from the president onto the institutions of the Parliament and the Prime Minister. Nevertheless the President remained the Commander-in-Chief, and notably used this power in response to the Twelve Generals' Letter.

The new government also started several large building projects, including state-sponsored housing and the building of the vital Zagreb-Split Highway, today's A1.

The country rebounded from a mild recession in 1998/1999 and achieved notable economic growth during the following years. The unemployment rate would continue to rise until 2001 when it finally started falling. Return of refugees accelerated as many homes were rebuilt by the government; most Croats had already returned (except for some in Vukovar), whereas only a third of the Serbs had done so, impeded by unfavorable property laws as well as ethnic and economic issues.

The Račan government is often credited with bringing Croatia out of semi-isolation of the Tuđman era. Croatia became a World Trade Organization (WTO) member on November 30, 2000. The country signed a Stabilization and Association Agreement (SAA) with the European Union in October 2001, and applied for membership in February/March 2003.

Sanader government (2003-2009)

In late 2003, new parliamentary elections were held and a reformed HDZ party won under leadership of Ivo Sanader, who became prime minister. After some delay caused by controversy over extradition of army generals to the ICTY, in 2004 the European Commission finally issued a recommendation that the accession negotiations with Croatia should begin. Its report on Croatia described it as a modern democratic society with a competent economy and the ability to take on further obligations, provided it continued the reform process.

The country was given EU applicant status on June 18, 2004 and a negotiations framework was set up in March 2005. Actual negotiations began after the capture of general Ante Gotovina in December 2005, which resolved outstanding issues with the ICTY in the Hague. However, numerous complications stalled the negotiating process, most notably during Slovenia's blockade of Croatia's EU accession from December 2008 until September 2009. Croatian accession to the EU is expected in the next years.

In August 2007, Croatia experienced its worst post-war tragedy. During the fires that ravaged its coast, 12 firemen died as a result of a fire on Kornat island.

Sanader was reelected in the closely contested 2007 parliamentary election. In June 2009, Sanader abruptly resigned his post, leaving scarce explanation for his actions, and rumours of involvement in various criminal cases became increasingly rampant. He tried to comeback in HDZ in 2010, but was then ejected, charged for corruption by authorities, and later arrested in Austria.

Kosor government (2009)

Jadranka Kosor assumed the head of the government following Sanader's resignation. Kosor introduced austerity measures to topple the economic crisis and launched an anti-corruption campaign aimed at public officials.

Jadranka Kosor signed an agreement with Borut Pahor, the premier of Slovenia, in November 2009, that ended Slovenia's blockade of Croatia's EU accession and allowed Croatian EU entry negotiations to proceed. On 30 June the accession agreement was concluded, giving Croatia the all-clear to join, with a projected accession date of 1 July 2013.[49]

In the first round of the 2010 presidential election the HDZ candidate Andrija Hebrang achieved an embarrassing 12% claiming third place, the lowest result for an HDZ presidential candidate ever. Ivo Josipović, the candidate of the largest opposition party, the Social Democratic Party of Croatia, won a landslide victory in the resulting runoff on January 10.

In June 2010, Kosor proposed loosening the labor law and making it more business friendly, in order to foster economic growth. This was greatly opposed by the unions: a petition demanding a referendum was unprecedentedly signed by over 700,000 citizens. Just as the Croatian labour law referendum, 2010 was being prepared, the government decided to drop the proposed changes, and the Constitutional Court ultimately declared the referendum issue moot, but ordered the government not to subject any changes to the labor law in the following year.

See also

- Art of Croatia

- Culture of Croatia

- Economy of Croatia

- List of rulers of Croatia

- History of Dalmatia

- History of Zagreb

- History of Europe

- History of the Mediterranean

- History of the Mediterranean region

- History of Hungary

- History of the Balkans

- Music of Croatia

- Central Europe

- Austria-Hungary

- NDH

- History of Yugoslavia

- Timeline of Croatian history

References

- ^ Igor Salopek (December 2010). "Krapina Neanderthal Museum as a Well of Medical Information". Acta Medico-Historica Adriatica (Hrvatsko znanstveno društvo za povijest zdravstvene kulture) 8 (2): 197–202. ISSN 1334-4366. http://hrcak.srce.hr/63530. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Tihomila Težak-Gregl (April 2008). "Study of the Neolithic and Eneolithic as reflected in articles published over the 50 years of the journal Opuscula archaeologica". Opvscvla Archaeologica Radovi Arheološkog zavoda (University of Zagreb, Faculty of Philosophy, Archaeological Department) 30 (1): 93–122. ISSN 0473-0992. http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=34026. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Jacqueline Balen (December 2005). "The Kostolac horizon at Vučedol". Opvscvla Archaeologica Radovi Arheološkog zavoda (University of Zagreb, Faculty of Philosophy, Archaeological Department) 29 (1): 25–40. ISSN 0473-0992. http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=26644. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Tihomila Težak-Gregl (December 2003). "Prilog poznavanju neolitičkih obrednih predmeta u neolitiku sjeverne Hrvatske [A Contribution to Understanding Neolithic Ritual Objects in the Northern Croatia Neolithic]" (in Croatian). Opvscvla Archaeologica Radovi Arheološkog zavoda (University of Zagreb, Faculty of Philosophy, Archaeological Department) 27 (1): 43–48. ISSN 0473-0992. http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=26644. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Hrvoje Potrebica; Marko Dizdar (July 2002). "Prilog poznavanju naseljenosti Vinkovaca i okolice u starijem željeznom dobu [A Contribution to Understanding Continuous Habitation of Vinkovci and its Surroundings in the Early Iron Age]" (in Croatian). Prilozi Instituta za arheologiju u Zagrebu (Institut za arheologiju) 19 (1): 79–100. ISSN 1330-0644. http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=1560. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ John Wilkes (1995). The Illyrians. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 114. ISBN 9780631198079. http://books.google.com/books/about/The_Illyrians.html?id=4Nv6SPRKqs8C. Retrieved 15 October 2011. "... in the early history of the colony settled in 385 BC on the island Pharos (Hvar) from the Aegean island Paros, famed for its marble. In traditional fashion they accepted the guidance of an oracle, ..."

- ^ Edward Gibbon; John Bagnell Bury; Daniel J. Boorstin (1995). The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. New York: Modern Library. p. 335. ISBN 9780679601487. http://books.google.com/books?id=bdKLyie1M50C. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ J. B. Bury (1923). History of the later Roman empire from the death of Theodosius I. to the death of Justinian. Macmillan Publishers. p. 408. http://books.google.com/books?id=Xw4fAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Andrew Archibald Paton (1861). Researches on the Danube and the Adriatic. Trübner. pp. 218–219. http://books.google.com/books?id=E_NBAAAAYAAJ. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Mužić (2007), pp. 249–293

- ^ Mužić (2007), pp. 157–160

- ^ Mužić (2007), pp. 169–170

- ^ Antun Ivandija (April 1968). "Pokrštenje Hrvata prema najnovijim znanstvenim rezultatima [Christianization of Croats according to the most recent scientific results]" (in Croatian). Bogoslovska smotra (University of Zagreb, Catholic Faculty of Theology) 37 (3–4): 440–444. ISSN 0352-3101.

- ^ Mužić (2007), pp. 195–198

- ^ Vladimir Posavec (March 1998). "Povijesni zemljovidi i granice Hrvatske u Tomislavovo doba [Historical maps and borders of Croatia in age of Tomislav]" (in Croatian). Radovi Zavoda za hrvatsku povijest 30 (1): 281–290. ISSN 0353-295X. http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=62779. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ Lujo Margetić (January 1997). "Regnum Croatiae et Dalmatiae u doba Stjepana II. [Regnum Croatiae et Dalmatiae in age of Stjepan II]" (in Croatian). Radovi Zavoda za hrvatsku povijest 29 (1): 11–20. ISSN 0353-295X. http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=76963. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ Ladislav Heka (October 2008). "Hrvatsko-ugarski odnosi od sredinjega vijeka do nagodbe iz 1868. s posebnim osvrtom na pitanja Slavonije [Croatian-Hungarian relations from the Middle Ages to the Compromise of 1868, with a special survey of the Slavonian issue]" (in Croatian). Scrinia Slavonica (Hrvatski institut za povijest – Podružnica za povijest Slavonije, Srijema i Baranje) 8 (1): 152–173. ISSN 1332-4853. http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=68144. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Povijest saborovanja [History of parliamentarism]" (in Croatian). Sabor. http://www.sabor.hr/Default.aspx?sec=404. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ Márta Font (July 2005). "Ugarsko Kraljevstvo i Hrvatska u srednjem vijeku [Hungarian Kingdom and Croatia in the Middlea Ages]" (in Croatian). Povijesni prilozi (Croatian Institute of History) 28 (28): 7–22. ISSN 0351-9767. http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=13778. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Zrinka Pešorda Vardić: The crown, the king and the town – the relation of Dubrovnik community toward the crown and the ruler in the beginning of movement against the Court (Croatian Institute of History)

- ^ a b Frucht 2005, p. 422-423

- ^ a b R. W. SETON -WATSON:The southern Slav question and the Habsburg Monarchy page 18

- ^ Charles W. Ingrao:The Habsburg monarchy, 1618–1815 page 15

- ^ Balkan Politics, TIME Magazine, March 31, 1923

- ^ Elections, TIME Magazine, February 23, 1925

- ^ The Opposition, TIME Magazine, April 6, 1925

- ^ Misha Glenny, The Balkans 1804–1999, Granta Books, London 1345, pp. 431–432

- ^ Josip Horvat, Politička povijest Hrvatske 1918–1929 (Political History of Croatia 1918–1929), Zagreb, 1938

- ^ Glenny, Misha. Balkans: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers, 1804–1999. New York, USA: Penguin Books, 2001. Pp. 431

USTASHE. "With the financial assistance of Italian government, Pavelic set about the construction of two main training camps, one in Hungary, one in Italy..." - ^ "United States Holocaust Memorial Museum about Jasenovac and Independent State of Croatia". Ushmm.org. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005449. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- ^ Genocide and Resistance in Hitler's Bosnia: The Partisans and the Chetniks, 1941-1943 pp20

- ^ Socialism of Sorts June 10, 1966

- ^ The Specter of Separatism, TIME Magazine, February 7, 1972

- ^ Conspiratorial Croats, TIME Magazine, June 5, 1972

- ^ Battle in Bosnia, TIME Magazine, July 24, 1972

- ^ New York Times, 14th December 1989

- ^ ICTY (June 12, 2007). "The Prosecutor vs. Milan Martic (paragraph 127–150)". ICTY. http://www.icty.org/x/cases/martic/tjug/en/070612.pdf. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ Ivo Goldstein, Croatia: A History, p. 220. (C. Hurst & Co, 2000)

- ^ Mihailo Crnobrnja, The Yugoslav Drama, p. 157; (McGill-Queens University Press, 1996)

- ^ Tim Judah (2001). The Serbs: History, Myth and the Destruction of Yugoslavia. Yale University Press. pp. 175–76, 244.

- ^ (Croatian) Narodne Novine: Odluka Predsjednika RH o raspisu referenduma

- ^ http://www.onwar.com/aced/nation/cat/croatia/fcroatia1991.htm.

- ^ Croatian report from 1995

- ^ Amnesty International report

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ "Franjo Tudjman: Father of Croatia". BBC News. 1999-12-11. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/294990.stm. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ^ "2001 World Press Freedom Review, Croatia". International Press Institute. http://www.freemedia.at/cms/ipi/freedom_detail.html?country=/KW0001/KW0003/KW0054/&year=2001. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ^ http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=IP/11/824&format=HTML&aged=0&language=EN&guiLanguage=en

Bibliography

- Roy Adkins; Lesley Adkins (2008). The War for All the Oceans. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780143113928. http://books.google.hr/books?id=3u9jdSlnGiMC. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Damir Agičić; Dragutin Feletar; AnitaFilipčić; Tomislav Jelić; Zoran Stiperski (2000) (in Croatian). Povijest i zemljopis Hrvatske: priručnik za hrvatske manjinske škole [History and Geography of Croatia: Minority School Manual]. ISBN 9789536235407. http://books.google.com/?id=9SArPwAACAAJ. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Ivo Banac (1984). The national question in Yugoslavia: origins, history, politics. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801494932. http://books.google.com/books?id=KfqbujXqQBkC. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Mark Biondich (2000). Stjepan Radić, the Croat Peasant Party, and the politics of mass mobilization, 1904–1928. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802082947. http://books.google.com/books?id=dZBgIIZ18WMC. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Peterjon Cresswell (10 July 2006). Time Out Croatia (First ed.). London, Berkeley & Toronto: Time Out Group Ltd & Ebury Publishing, Random House. ISBN 9781904978701. http://books.google.com/?id=kwOYuX-Oy18C. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- Sharon Fisher (2006). Political change in post-Communist Slovakia and Croatia: from nationalist to Europeanist. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403972866. http://books.google.com/?id=7TiFZQHwAjQC. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Joerg Forbrig; Pavol Demeš (2007). Reclaiming democracy: civil society and electoral change in central and eastern Europe. The German Marshall Fund of the United States. ISBN 9788096963904. http://books.google.com/?id=MWTrLQAACAAJ. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Richard C. Frucht (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576078006. http://books.google.hr/books?id=lVBB1a0rC70C. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Mirjana Kasapović, ed (2001) (in Croatian). HRVATSKA POLITIKA 1990.-2000. [Croatian Politics 1990–2000]. University of Zagreb, Faculty of Political Science. ISBN 9789536457083. http://books.google.com.br/books/about/Hrvatska_politika_1990_2000.html?id=z7sVAQAAIAAJ. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Matjaž Klemenčič; Mitja Žagar (2004). The former Yugoslavia's diverse peoples: a reference sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576072943. http://books.google.hr/books?id=ORSMBFwjAKcC. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- Frederic Chapin Lane (1973). Venice, a Maritime Republic. JHU Press. ISBN 9780801814600. http://books.google.com/?id=PQpU2JGJCMwC. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Branka Magaš (2007). Croatia through history: the making of a European state. Saqi Books. ISBN 9780863567759. http://books.google.com/books?id=OY5pAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Ivan Mužić (2007) (in Croatian) (PDF). Hrvatska povijest devetoga stoljeća [Croatian Ninth Century History]. Naklada Bošković. ISBN 9789532630343. http://www.muzic-ivan.info/hrvatska_povijest.pdf. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

External links

- Croatian Institute of History

- Museum Documentation Center

- The Croatian History Museum

- Journal of Croatian Studies

- Short History of Croatia

- Overview of History, Culture, and Science

- Overview of History, Culture and Science of Croatia

- WWW-VL History:Croatia

- Dr. Michael McAdams: Croatia — Myth and Reality

- History of Croatia as an introduction to the battle of Vukovar

- Historical Maps of Croatia

- Croatia under Tomislav -from Nada Klaic book

- The History Files: [3]

History of Europe Prehistoric Europe Classical Antiquity Classical Greece · Roman Republic · Hellenistic period · Roman Empire · Late Antiquity · Early Christianity · Crisis of the 3rd century · Fall of the Roman EmpireMiddle Ages Early Middle Ages · Migration Period · Byzantine Empire · Christianization · Kievan Rus · High Middle Ages · Holy Roman Empire · Crusades · Feudalism · Late Middle Ages · Hundred Years' War · RenaissanceEarly Modern Europe Reformation · Age of Discovery · Baroque · Thirty Years' War · Absolutism · Ottoman Empire · Portuguese Empire · Spanish Empire · Early modern France · Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth · Swedish Empire · Dutch Republic · British Empire · Habsburg Empire · Russian EmpireModern history See also History of Europe by country Sovereign

states- Albania

- Andorra

- Armenia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belarus

- Belgium

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bulgaria

- Croatia

- Cyprus

- Czech Republic

- Denmark

- Estonia

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- Iceland

- Ireland

- Italy

- Kazakhstan

- Latvia

- Liechtenstein

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Macedonia

- Malta

- Moldova

- Monaco

- Montenegro

- Netherlands

- Norway

- Poland

- Portugal

- Romania

- Russia

- San Marino

- Serbia

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Spain

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Turkey

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- (England

- Northern Ireland

- Scotland

- Wales)

- Vatican City

States with limited

recognition- Abkhazia

- Kosovo

- Nagorno-Karabakh

- Northern Cyprus

- South Ossetia

- Transnistria

Dependencies

and other territories- Åland

- Faroe Islands

- Gibraltar

- Guernsey

- Jan Mayen

- Jersey

- Isle of Man

- Svalbard

Other entities - European Union

- Sovereign Military Order of Malta

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.