- Cinema of Japan

-

Cinema of

Japan

List of Japanese films 1898–1919 1920s 1930s 1940s 1950s 1950 1951 1952 1953 1954

1955 1956 1957 1958 19591960s 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964

1965 1966 1967 1968 19691970s 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974

1975 1976 1977 1978 19791980s 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984

1985 1986 1987 1988 19891990s 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994

1995 1996 1997 1998 19992000s 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

2005 2006 2007 2008 20092010s 2010 2011 2012 East Asian cinema

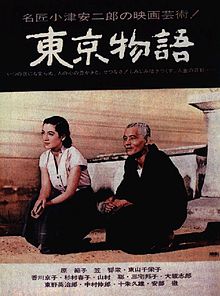

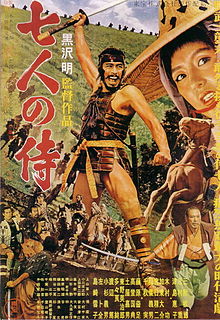

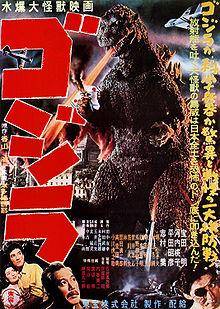

The cinema of Japan (日本映画 Nihon eiga) has a history that spans more than 100 years. Japan has one of the oldest and largest film industries in the world – as of 2009 the fourth largest by number of feature films produced.[1] Movies have been produced in Japan since 1897, when the first foreign cameramen arrived. Notable films from the Japanese film industry are: Tokyo Story, Seven Samurai, Ugetsu, Ikiru, Godzilla, among many others. In a ranking of the best films produced in Asia by the Sight & Sound British film magazine, Japan made up 8 of the top 12, with Tokyo Story being ranked number one. In the United States, Japan has won the Academy Award for the Best Foreign Language Film 4 times, again more than any other country in Asia.

Contents

Genres

- Anime: Animation. Anime refers to "Japanese animation" in English.

- Jidaigeki: period pieces set during the Edo period (1603–1868) or earlier.

- Samurai cinema, a subgenre of jidaigeki, also known as chambara (onomatopoeia describing the sound of swords clashing).

- Ninja: films about ninja

- J-Horror: horror films such as Ring

- Cult Horror, such as Battle Royale or Suicide Club

- Kaiju: monster films, such as Godzilla

- Pink films: softcore pornographic films. Often more socially engaged and aesthically well crafted than simple pornography.

- Yakuza films: films about Yakuza mobsters.

- Seishun eiga: films about teenagers

- Gendaigeki: modern life films

- Shomingeki: realistic films about common working people

History

Silent Era

Though the kinetoscope was first shown commercially by Thomas Edison in the United States in 1894, the first showing in Japan took place in November 1896. The Vitascope and the Lumière Brothers' Cinematograph were first presented in Japan in March 1897,[2] and Lumière cameramen were the first to shoot films in Japan.[3] Moving pictures, however, were not an entirely new experience for the Japanese because of their rich tradition of pre-cinematic devices such as gentō (utsushi-e) or the magic lantern.[4][5] The first successful Japanese film was viewed in late 1897 and showed various well-known sights in Tokyo.[6]

1898 saw some of the first ghost films produced in Japan, the Shirō Asano shorts Bake Jizo (Jizo the Spook / 化け地蔵) and Shinin no sosei (Resurrection of a Corpse).[7] The first documentary, the short Geisha no teodori (芸者の手踊り), was made in June 1899. Tsunekichi Shibata made a number of early films, including Momijigari, a 1899 record of two famous actors performing a scene from a well-known kabuki play. Early films were influenced by traditional theater – for example, kabuki and bunraku.

Most early Japanese cinema theatres employed benshi, narrators whose dramatic readings accompanied the film and its musical score. As in the West, the score was often performed live.[8]

In 1908, Shōzō Makino, considered the pioneering director of Japanese film, began his influential career with Honnōji gassen (本能寺合戦), produced for Yokota Shōkai. Shōzō recruited Matsunosuke Onoe, a former kabuki actor, to star in his productions. Subsequently, Onoe became Japan's first film star, appearing in over 1,000 films, mostly shorts, between 1909 and 1926. The pair pioneered the jidaigeki genre.[9] Tokihiko Okada was a popular romantic lead of the same era, similar in appeal to Rudolph Valentino.

The first female Japanese performer to appear in a film professionally was the dancer/actress Tokuko Nagai Takagi, who appeared in four shorts for the American-based Thanhouser Company between 1911 and 1914.[10]

Among intellectuals, criticism of Japanese cinema grew in the 1910s. Criticism of cinema, beginning with early film magazines such as Katsudō shashinkai (begun in 1909) and a full-length book written by Yasunosuke Gonda in 1914, developed through the decade as early film critics chastised the work of studios like Nikkatsu and Tenkatsu for being too theatrical (using, for instance, elements from kabuki and shinpa such as onnagata) and for not utilizing what were considered more cinematic techniques to tell stories, instead relying on benshi. In his 1917 film The Captain's Daughter, Masao Inoue started using techniques new to the silent film era, such as the close-up and cut back. In a movement later called the Pure Film Movement, writers in magazines such as Kinema Record called for a broader use of such cinematic techniques. Some of these critics, such as Norimasa Kaeriyama, went on to put their ideas into practice by directing such films as The Glow of Life (1918). The Pure Film Movement was central in the development of the gendaigeki and scriptwriting.[11] New studios established around 1920, such as Shochiku and Taikatsu, aided the cause for reform. At Taikatsu, Thomas Kurihara directed films scripted by the novelist Junichiro Tanizaki, who was a strong advocate of film reform.[12] Even Nikkatsu produced reformist films under the direction of Eizō Tanaka. By the mid-1920s, actresses had replaced onnagata and films used more of the devices pioneered by Inoue. Some of the most discussed silent films from Japan are those of Kenji Mizoguchi, whose later works (e.g., The Life of Oharu) are still highly regarded.

Japanese films gained popularity in the mid-1920s against foreign films, in part fueled by the popularity of movie stars. Some stars, such as Tsumasaburo Bando, Kanjūrō Arashi, Chiezō Kataoka, Takako Irie and Utaemon Ichikawa, were inspired by Makino Film Productions and formed their own independent production companies. Directors such as Hiroshi Inagaki, Mansaku Itami and Sadao Yamanaka honed their skills at such independent studios. Director Teinosuke Kinugasa created his own production company to produce the experimental masterpiece A Page of Madness, starring Masao Inoue, in 1926.[13] Many of these companies, while surviving during the silent era against major studios like Nikkatsu, Shochiku, Teikine, and Toa Studios, could not survive the coming of sound and the cost involved in converting to sound.

With the rise of left-wing political movements and labor unions at the end of the 1920s, films with left-wing "tendencies" (so-called tendency films) gained popularity, with prominent examples being directed by Kenji Mizoguchi, Daisuke Itō, Shigeyoshi Suzuki, and Tomu Uchida. In contrast with these commercially produced 35 mm films, the Marxist Proletarian Film League of Japan (Prokino) made works independently in smaller gauges (such as 9.5mm and 16mm), with more radical intentions.[14] Tendency films suffered from severe censorship heading into the 1930s, and Prokino members were arrested and the movement effectively crushed. Such moves by the government had profound effects on the expression of political dissent in 1930s cinema.

A later version of The Captain's Daughter was one of the first talkie films. It used the Mina Talkie System, which later split into two groups; one remained the Mina Talkie System, while the other became the Iisutofyon Talkie System that was used to make Tojo Masaki's films.

The effects of the 1923 earthquake, the Allied bombing of Tokyo during World War II, as well as the natural effects of time and Japan's humidity on inflammable and unstable Nitrate film have resulted in a great dearth of surviving films from this period.

1930s

Unlike in the West, silent films were still being produced in Japan well into the 1930s. A few Japanese sound shorts were made in the 1920s and 1930s, but Japan's first feature-length talkie was Fujiwara Yoshie no furusato (1930), which used the Mina Talkie System. Notable talkies of this period include Mikio Naruse's Wife, Be Like A Rose! (Tsuma Yo Bara No Yoni, 1935), which was one of the first Japanese films to gain a theatrical release in the U.S.; Yasujiro Ozu's An Inn in Tokyo, considered a precursor to the neorealism genre; Kenji Mizoguchi's Sisters of the Gion (Gion no shimai, 1936); Osaka Elegy (1936); Sadao Yamanaka's Humanity and Paper Balloons (1937); and The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939).

The 1930s also saw increased government involvement in cinema, which was symbolized by the passing of the Film Law, which gave the state more authority over the film industry, in 1939. The government encouraged some forms of cinema, producing propaganda films and promoting documentary films (also called bunka eiga or "culture films"), with important documentaries being made by directors such as Fumio Kamei.[15] Realism was in favor; film theorists such as Taihei Imamura advocated for documentary, while directors such as Hiroshi Shimizu and Tomotaka Tasaka produced fiction films that were strongly realistic in style.

1940s

Because of World War II and the weak economy, unemployment became widespread in Japan. The weakness of the economy also had a very detrimental effect on the cinema industry. During this period, when Japan was expanding its growing Empire, the Japanese government saw cinema as the perfect propaganda tool to show people the glory and invincibility of the Empire of Japan. Thus, many films from this period depict deeply patriotic and militaristic themes. In 1942 Kajiro Yamamoto’s film Hawai Mare oki kaisen or “The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malay” portrayed the attack on Pearl Harbor, amazingly reproduced with a miniature scale model, among other special effects that Eiji Tsuburaya (a special effects director) was in charge of.

Akira Kurosawa made his feature film debut with Sugata Sanshiro in 1943. With the SCAP occupation following the end of WWII, Japan was exposed to over a decade's worth of American animation that had been banned under the war-time government. The first collaborations between Kurosawa and actor Toshiro Mifune were Drunken Angel in 1948 and Stray Dog in 1949. Yasujiro Ozu directed the critically and commercially successful Late Spring in 1949.

The Mainichi Film Award was created in 1946.

1950s

The 1950s were the Golden Age of Japanese cinema.[16] Three Japanese films from this decade (Rashomon, Seven Samurai and Tokyo Story) made the Sight & Sound's 2002 Critics and Directors Poll for the best films of all time.[17] The period after the American Occupation led to a rise in diversity in movie distribution thanks to the increased output and popularity of the film studios of Toho, Daiei, Shochiku, Nikkatsu, and Toei.

The decade started with Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon (1950), which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and marked the entrance of Japanese cinema onto the world stage. It was also the breakout role for legendary star Toshirō Mifune.[18] In 1953 Entotsu no mieru basho by Heinosuke Gosho was in competition at the 3rd Berlin International Film Festival.

The first Japanese film in color was Carmen Comes Home directed by Keisuke Kinoshita and released in 1951. There was also a black-and-white version of this film available. Gate of Hell, a 1953 film by Teinosuke Kinugasa, was the first movie that filmed using Eastmancolor film, Gate of Hell was both Daiei's first color film and the first Japanese color movie to be released outside of Japan, receiving an Oscar in 1954 for Best Costume Design by Sanzo Wada and an Honorary Award for Best Foreign Language Film. It also won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, the first Japanese film to achieve that honour.

The year 1954 saw two of Japan's most influential films released. The first was the Kurosawa epic Seven Samurai, about a band of hired samurai who protect a helpless village from a rapacious gang of thieves, which was remade in the West as The Magnificent Seven. The same year, Ishirō Honda released the anti-nuclear horror film Gojira, which was translated in the West as Godzilla. Though it was severely edited for its Western release, Godzilla became an international icon of Japan and spawned an entire industry of Kaiju films. Also in 1954, both another Kurosawa film, Ikiru, and Yasujiro Ozu's Tokyo Story were in competition at the 4th Berlin International Film Festival.

In 1955, Hiroshi Inagaki won an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film for Part I of his Samurai trilogy and in 1958 won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival for Rickshaw Man. Kon Ichikawa directed two anti-war dramas: The Burmese Harp (1956), which was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards, and Fires On The Plain (1959), along with Enjo (1958), which was adapted from Yukio Mishima's novel Temple Of The Golden Pavilion. Masaki Kobayashi made two of the three films which would collectively become known as The Human Condition Trilogy: No Greater Love (1958), and The Road To Eternity (1959). The trilogy was completed in 1961, with A Soldier's Prayer.

Kenji Mizoguchi directed The Life of Oharu (1952), Ugetsu (1953) and Sansho the Bailiff (1954). He won the Silver Bear at the Venice Film Festival for Ugetsu. Mikio Naruse made Repast (1950), Late Chrysanthemums (1954), The Sound of the Mountain (1954) and Floating Clouds (1955). Yasujiro Ozu directed Good Morning (1959) and Floating Weeds (1958), which was adapted from his earlier silent A Story of Floating Weeds (1934), and was shot by Rashomon/Sansho the Bailiff cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa.

The Blue Ribbon Awards were established in 1950. The first winner for Best Film was Until We Meet Again by Tadashi Imai.

1960s

Production in the Japanese film industry reached its quantitative peak in the 1960s, with 547 movies being produced.[citation needed] It can also be regarded as the peak years of the Japanese New Wave movement, which began in the 1950s and continued through the early 1970s. Akira Kurosawa directed the 1961 classic Yojimbo, which many believe was at least partially inspired by John Ford Westerns and film noir classics; Yojimbo in turn influenced Westerns that followed, especially Sergio Leone's Fistful of Dollars. Yasujiro Ozu made his final film, An Autumn Afternoon, in 1962. Mikio Naruse directed the wide screen melodrama When a Woman Ascends the Stairs in 1960; his final film was 1967's Scattered Clouds.

Kon Ichikawa captured the watershed 1964 Olympics in his three-hour documentary Tokyo Olympiad (1965). Seijun Suzuki was fired by Nikkatsu for "making films that don't make any sense and don't make any money" after his surrealist yakuza flick Branded to Kill (1967).

Nagisa Oshima, Kaneto Shindo, Masahiro Shinoda, Susumu Hani and Shohei Imamura emerged as major filmmakers during the decade. Oshima's Cruel Story of Youth, Night and Fog in Japan and Death By Hanging, along with Shindo's Onibaba, Hani's She And He and Imamura's The Insect Woman, became some of the better-known examples of Japanese New Wave filmmaking. Documentary played a crucial role in the New Wave, as directors such as Hani, Kazuo Kuroki, Toshio Matsumoto, and Hiroshi Teshigahara moved from documentary into fiction film, while feature filmmakers like Oshima and Imamura also made documentaries. Shinsuke Ogawa and Noriaki Tsuchimoto became the most important documentarists: "two figures [that] tower over the landscape of Japanese documentary."[19]

Teshigahara's Woman in the Dunes (1964) won the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival, and was nominated for Best Director and Best Foreign Language Film Oscars. Masaki Kobayashi's Kwaidan (1965) also picked up the Special Jury Prize at Cannes and received a nomination for Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards. Bushido, Samurai Saga by Tadashi Imai won the Golden Bear at the 13th Berlin International Film Festival. Immortal Love by Keisuke Kinoshita and Twin Sisters of Kyoto and Portrait of Chieko, both by Noboru Nakamura, also received nominations for Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards. Lost Spring, also by Nakamura, was in competition for the Golden Bear at the 17th Berlin International Film Festival.

1970s

Nagisa Oshima directed In the Realm of the Senses (1976), a film detailing a crime of passion involving Sada Abe set in the 1930s. Controversial for its explicit sexual content, it has never been seen uncensored in Japan. However, the pink film industry became the stepping stone for young independent filmmakers of Japan.

Toshiya Fujita made the revenge film Lady Snowblood in 1973. It would go on to become a popular cult film in the West. In the same year, Yoshishige Yoshida made the film Coup d'État, a portrait of Ikki Kita, the leader of the Japanese coup of February 1936. Its experimental cinematography and mise-en-scène, as well as its avant-garde score by Ichiyanagi Sei, garnered it wide critical acclaim within Japan.

In 1976 the Hochi Film Award was created. The first winner for Best Film was The Inugamis by Kon Ichikawa.

Kinji Fukasaku completed the epic Battles Without Honor and Humanity series of yakuza films. Yoji Yamada introduced the commercially successful Tora-San series, while also directing other films, notably the popular The Yellow Handkerchief, which won the first Japan Academy Prize for Best Film in 1978. New wave filmmakers Susumu Hani and Shohei Imamura retreated to documentary work, though Imamura made a dramatic return to feature filmmaking with Vengeance Is Mine (1979).

Dodes'ka-den by Akira Kurosawa and Sandakan No. 8 by Kei Kumai were nominated to the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

1980s

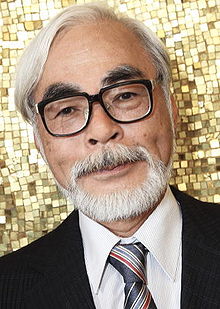

During the 1980s, anime gained in popularity, with new animated movies released every summer and winter, often based upon popular television anime. Mamoru Oshii released his landmark Angel's Egg in 1983. Hayao Miyazaki adapted his manga series Nausicaä of the Valley of Wind into a feature film of the same name in 1984. Katsuhiro Otomo followed suit with Akira in 1988.

Akira Kurosawa directed Kagemusha (1980), which won the Palme d'Or at the 1980 Cannes Film Festival, and Ran (1985). Likewise, Seijun Suzuki made a comeback, beginning with Zigeunerweisen in 1980. Shohei Imamura won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival for The Ballad of Narayama (1983).

Yoshishige Yoshida made A Promise (1986), his first film since 1973's Coup d'État. It centered upon generational conflict during the height of Japan's economic boom, and nostalgia for traditional ways of life; the work received more international recognition than Yoshida's previous films, and was selected to be screened in the Un Certain Regard section at Cannes.

Juzo Itami directed his first film, Ososhiki (The Funeral), in 1984. He achieved both critical and box office success with his quirky "Japanese Noodle Western" comedy Tampopo in 1985, which remains popular. Kiyoshi Kurosawa, who would generate international attention beginning in the mid-1990s, also made his initial debut in the 1980s with pink films and genre horror.

The availability of home video made possible the creation of a direct-to-video film industry, called V-Cinema.

1990s

Because of economic recessions, the number of movie theaters in Japan had been steadily decreasing since the 1960s. The 1990s saw the reversal of this trend and the introduction of the Multiplex in Japan.[20]

Takeshi Kitano emerged as a significant filmmaker with works such as Sonatine (1993), Kids Return (1996) and Hana-bi (1997), which was given the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. Shohei Imamura again won the Golden Palm (shared with Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami), this time for The Eel (1997). He became the fourth two-time recipient, joining Alf Sjöberg, Francis Ford Coppola and Bille August.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa gained international recognition following the release of Kyua (1997). Takashi Miike launched a prolific career, making up to 50 films in a decade, building up an impressive portfolio with titles such as, Audition (1999), Dead or Alive (1999) and The Bird People in China (1998). Former documentary filmmaker Hirokazu Koreeda launched an acclaimed feature career with Maborosi (1996) and After Life (1999).

Hayao Miyazaki directed two mammoth box office and critical successes, Porco Rosso (1992) – which beat E.T. (1982) as the highest-grossing film in Japan – and Princess Mononoke (1997), which also claimed the top box office spot until Titanic (1997).

Several new anime directors rose to widespread recognition, bringing with them notions of anime as not only entertainment, but modern art. Mamoru Oshii released the internationally acclaimed philosophical science fiction action film Ghost in the Shell, based on the manga by Masamune Shirow, in 1996. The film garnered great success and recognition in theatrical releases worldwide, and eight years later Oshii directed a sequel. Satoshi Kon directed the award-winning psychological thriller Perfect Blue, based on a novel by Toshiki Satō. The film was theatrically released to decent commercial and considerable critical success in America and several other countries around the world. Hideaki Anno also gained considerable recognition after the release of his successful and controversial psychological science fiction epic Neon Genesis Evangelion, which started as a TV series in 1995 and concluded with the theatrical release of The End of Evangelion, the series' postmodern, apocalyptic conclusion, in 1997. (The film was not released internationally until the early 2000s, and then in straight-to-DVD format.) Evangelion is widely considered to be one of the most influential anime of all time.[citation needed]

2000s

The 2000s have been the most productive period for Japanese cinema since 1955.[citation needed] In 2000 Battle Royale was released, based on a popular novel by the same name. In 2002, Dolls was released, followed by a high-budget remake, Zatoichi in 2003, both directed and written by Takeshi Kitano. The J-Horror films Ringu, Kairo, Dark Water, Yogen, the Grudge series and One Missed Call were remade in English and met with commercial success. In 2004, Godzilla: Final Wars, directed by Ryuhei Kitamura, was released to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Godzilla. In 2005, director Seijun Suzuki made his 56th film, Princess Raccoon. Hirokazu Koreeda claimed film festival awards around the world with two of his films Distance and Nobody Knows. Takashi Miike's prolific career continued. Yoji Yamada, long time director of the popular Otoko wa Tsurai yo comedy series, emerged in the 2000s with a trilogy of acclaimed revisionist samurai films, beginning with 2002's Twilight Samurai, followed by The Hidden Blade in 2004 and Love and Honor in 2006.

The number of movies being shown in Japan has steadily been increasing, with about 821 films released in 2006. Movies based on Japanese television series were especially popular during this period.

In anime, Hayao Miyazaki came out of retirement to direct Spirited Away in 2001, breaking Japanese box office records and winning the U.S. Academy Award for Best Animated Feature. The film also won the Golden Bear at the 52nd Berlin International Film Festival. Miyazaki's subsequent films, Howl's Moving Castle and Ponyo, were released in 2004 and 2008 respectively.

In 2004, Mamoru Oshii released the anime movie Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence (known in Japan simply as "Innocence"), which, like the first film, received critical praise around the world; it was the sixth-ever animated film to be included in the Cannes Film Festival, and one of only two to become a finalist for the Palme D'Or award. His 2008 film The Sky Crawlers was met with similarly positive international reception. Satoshi Kon also released three quieter, but nonetheless highly successful films in 2001, 2003 and 2006 respectively: Millennium Actress, Tokyo Godfathers, and Paprika. Katsuhiro Otomo released Steamboy, his first animated project since the 1995 short film compilation Memories, in 2004, with subsequent theatrical releases internationally. In collaboration with Studio 4C, American director Michael Arias released Tekkon Kinkreet in 2008, to international acclaim. After several years of directing primarily lower-key live-action films, Hideaki Anno formed his own production studio and revisited his still-popular Evangelion franchise with the Rebuild of Evangelion tetralogy, a new series of films providing an alternate retelling of the original story. The first film, Evangelion: 1.0 You Are (Not) Alone released to considerable success in September 2007; after several delays in production, the second film, Evangelion: 2.0 You Can (Not) Advance was released in June 2009. The release schedule for the final two films has yet to be determined.

Anime films now account for 60 percent of Japanese film production. The 1990s and 2000s is considered to be "Japanese Cinema's Second Golden Age", due to the immense popularity of anime, both within Japan and overseas.[16]

In February 2000, the Japan Film Commission Promotion Council was established. On November 16, 2001, the Japanese Foundation for the Promotion of the Arts laws were presented to the House of Representatives. These laws were intended to promote the production of media arts, including film scenery, and stipulate that the government – on both the national and local levels – must lend aid in order to preserve film media. The laws were passed on November 30 and came into effect on December 7. In 2003, at a gathering for the Agency of Cultural Affairs, twelve policies were proposed in a written report to allow public-made films to be promoted and shown at the Film Center of the National Museum of Modern Art.

2010s

Three films have so far received international recognition by being selected to compete in major film festivals: Caterpillar by Kōji Wakamatsu was in competition for the Golden Bear at the 60th Berlin International Film Festival and won the Silver Bear for Best Actress, Outrage by Takeshi Kitano was in competition for the Palme d'Or at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival and Himizu, by Sion Sono was in competition for the Golden Lion at the 68th Venice International Film Festival.

See also

- Cinema of the world

- History of cinema

- Japan Academy Prize

- List of Japanese actors

- List of Japanese actresses

- List of Japanese film directors

- List of Japanese films

- List of Japanese language films

- List of Japanese movie studios

- Nuberu bagu (The Japanese New Wave)

- Pink film

- Seiyū

- Tendency film

- List of Japanese submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

- Television in Japan

Notes

- ^ "Top 50 countries ranked by number of feature films produced, 2004–2009". Screen Australia. http://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/research/statistics/acompfilms.asp. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ Tsukada, Yoshinobu (1980). Nihon eigashi no kenkyū: katsudō shashin torai zengo no jijō. Gendai Shokan.

- ^ Yoshishige Yoshida; Masao Yamaguchi; Naoyuki Kinoshita, ed. Eiga denrai: shinematogurafu to <Meiji no Nihon>. 1995: Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 4000002104.

- ^ Iwamoto, Kenji (2002). Gentō no seiki: eiga zenʾya no shikaku bunkashi = Centuries of magic lanterns in Japan. Shinwasha. ISBN 4916087259.

- ^ Kusahara, Machiko (1999). "Utushi-e (Japanese Phantasmagoria)". Media Art Plaza. http://plaza.bunka.go.jp/bunka/museum/kikaku/exhibition02/english/index-e.html. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- ^ Reading a Japanese Film: Cinema in Context. http://books.google.com/books?id=ICqSfjUqIpMC&dq=reading+a+japanese+film+cinema+in+context&printsec=frontcover&source=bl&ots=RctlRp4kGG&sig=JuzSL46P1ZuPtG7nOT-dXFV89qo&hl=en&ei=qQWoSov_J4PkNay1lKQI&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ^ Seek Japan | J-Horror: An Alternative Guide

- ^ For more on benshi, see the books:

- ^ "Who's Who in Japanese Silent Films". Matsuda Film Productions. http://www.matsudafilm.com/matsuda/c_pages/c_de.html. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ Cohen, Aaron M.. "Tokuko Nagai Takaki: Japan's First Film Actress". Bright Lights Film Journal 30 (October 2000). http://www.brightlightsfilm.com/30/tokuko.html. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ See Bernardi.

- ^ See Lamarre.

- ^ See Gerow, A Page of Madness.

- ^ Nornes, Japanese Documentary Film, pp. 19–47.

- ^ See Nornes, Japanese Documentary Film.

- ^ a b Dave Kehr, Anime, Japanese Cinema's Second Golden Age, The New York Times, January 20, 2002.

- ^ BFI | Sight & Sound | Top Ten Poll 2002

- ^ Prince, Stephen (1999). The Warrior's Camera. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01046-3., p.127.

- ^ Nornes, Abé Mark (2011). "Noriaki Tsuchimoto and the Reverse View Documentary". The Documentaries of Noriaki Tsuchimoto. Zakka Films. pp. 2–4.

- ^ Ja.wikipedia.org

Bibliography

- Anderson, Joseph L.; Donald Richie (1982). The Japanese Film: Art and Industry (Expanded ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691007926.

- The Benshi-Japanese Silent Film Narrators. Tokyo: Urban Connections. 2001. ISBN 4-900849-51-0.

- Bernardi, Joanne (2001). Writing in Light: The Silent Scenario and the Japanese Pure Film Movement. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0814329268.

- Bordwell, David (1988). Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691008221. Available online at the Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan

- Bowyer, Justin, ed (2004). The Cinema of Japan and Korea. Wallflower Press, London. ISBN 1-904764-11-8.

- Burch, Nöel (1979). To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema. University of California Press. ISBN 0520036050. Available online at the Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan

- Cazdyn, Eric (2002). The Flash of Capital: Film and Geopolitics in Japan. Duke University Press. ISBN 0822329123.

- Desser, David (1988). Eros Plus Massacre: An Introduction to the Japanese New Wave Cinema. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253204690.

- Dym, Jeffrey A. (2003). Benshi, Japanese Silent Film Narrators, and Their Forgotten Narrative Art of Setsumei: A History of Japanese Silent Film Narration. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-6648-7. (review)

- Gerow, Aaron (2008). A Page of Madness: Cinema and Modernity in 1920s Japan. Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan. ISBN 9781929280513.

- Gerow, Aaron (2010). Visions of Japanese Modernity: Articulations of Cinema, Nation, and Spectatorship, 1895–1925. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520254565.

- Hirano, Kyoko (1992). Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo: The Japanese Cinema under the Occupation, 1945–1952. Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 1560981571.

- Lamarre, Thomas (2005). Shadows on the Screen: Tanizaki Junʾichirō on Cinema and "Oriental" Aesthetics. Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan. ISBN 1929280327.

- Mellen, Joan (1976). The Waves At Genji's Door: Japan Through Its Cinema. Pantheon, New York. ISBN 0-394-49799-6.

- Nolletti, Jr., Arthur; Desser, David, eds (1992). Reframing Japanese Cinema: Authorship, Genre, History. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253341086.

- Nornes, Abé Mark (2003). Japanese Documentary Film: The Meiji Era through Hiroshima. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816640459.

- Nornes, Abé Mark (2007). Forest of Pressure: Ogawa Shinsuke and Postwar Japanese Documentary. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816649081.

- Nornes, Abé Mark; Gerow, Aaron (2009). Research Guide to Japanese Film Studies. Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan. ISBN 978192928053X.

- Prince, Stephen (1999). The Warrior's Camera. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01046-3.

- Richie, Donald (2005). A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a Selective Guide to DVDs and Videos. Kodansha America. ISBN 4-7700-2995-0.

- Sato, Tadao (1982). Currents In Japanese Cinema. Kodansha America. ISBN 0-87011-815-3.

- Wada-Marciano, Mitsuyo (2008). Nippon Modern: Japanese Cinema of the 1920s and 1930s. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824832407.

External links

- Japan Society Film Program – Offering curated film series with international and US premieres, special guests, lectures and the annual JAPAN CUTS: Festival of Contemporary Japanese Cinema

- Toki Akihiro & Mizuguchi Kaoru (1996) A History of Early Cinema in Kyoto, Japan (1896–1912). Cinematographe and Inabata Katsutaro.

- Film in Japan

- Kato Mikiro (1996) A History of Movie Theaters and Audiences in Postwar Kyoto, the Capital of Japanese Cinema.

- Asia Society: The Cinema Scene – Asia Society's regular podcast program containing news, reviews and interviews related to Asian Film

- Japanese Movie Database (in Japanese)

- Kinema Club

- Midnight Eye

- Resources for the Study of Japanese Cinema at the University of Iowa Library

- Japanese Cinema to 1960 by Gregg Rickman

- The Problem of Identity in Contemporary Japanese Horror Films, discussion paper by Timothy Iles in the Electronic journal of contemporary japanese studies, 6 October 2005.

- Female Voices, Male Words: Problems of Communication, Identity and Gendered Social Construction in Contemporary Japanese Cinema, discussion paper by Timothy Iles in the *Reviews of Japanese Films, in the electronic journal of contemporary japanese studies

- Japan Cultural Profile – national cultural portal for Japan created by Visiting Arts/Japan Foundation

- Japanese Film Festival (Singapore) – An annual curated film program focusing on classic Japanese cinema and new currents, with regular guest directors and actors.

- Movies Books Guide - Best of Japanese Movies

- JapaneseDirectors.com - Top director profiles and guide to English subtitled DVD releases

Cinema of Japan Actors · Awards · Directors (list) · Cinematographers · Composers · Editors · Festivals · Producers · ScreenwritersGenres Gendai-geki · Jidaigeki · Pink film · Samurai cinema · Shomin-geki · Tendency film · Yakuza film (Gokudō)Films

3-D films · Silent films · Short films · Television films · Films by directorFilms by genreAction · Anime · Comedy · Documentary · Drama · Horror · Jidaigeki · Mystery · Pink · Romance · Science fiction · Tokusatsu · Yakuza1898–1919 · 1920s · 1930s · 1940s · 1950 · 1951 · 1952 · 1953 · 1954 · 1955 · 1956 · 1957 · 1958 · 1959 · 1960 · 1961 · 1962 · 1963 · 1964 · 1965 · 1966 · 1967 · 1968 · 1969 · 1970 · 1971 · 1972 · 1973 · 1974 · 1975 · 1976 · 1977 · 1978 · 1979 · 1980 · 1981 · 1982 · 1983 · 1984 · 1985 · 1986 · 1987 · 1988 · 1989 · 1990 · 1991 · 1992 · 1993 · 1994 · 1995 · 1996 · 1997 · 1998 · 1999 · 2000 · 2001 · 2002 · 2003 · 2004 · 2005 · 2006 · 2007 · 2008 · 2009 · 2010 · 2011 · 2012

3-D films · Silent films · Short films · Television films · Films by directorFilms by genreAction · Anime · Comedy · Documentary · Drama · Horror · Jidaigeki · Mystery · Pink · Romance · Science fiction · Tokusatsu · Yakuza1898–1919 · 1920s · 1930s · 1940s · 1950 · 1951 · 1952 · 1953 · 1954 · 1955 · 1956 · 1957 · 1958 · 1959 · 1960 · 1961 · 1962 · 1963 · 1964 · 1965 · 1966 · 1967 · 1968 · 1969 · 1970 · 1971 · 1972 · 1973 · 1974 · 1975 · 1976 · 1977 · 1978 · 1979 · 1980 · 1981 · 1982 · 1983 · 1984 · 1985 · 1986 · 1987 · 1988 · 1989 · 1990 · 1991 · 1992 · 1993 · 1994 · 1995 · 1996 · 1997 · 1998 · 1999 · 2000 · 2001 · 2002 · 2003 · 2004 · 2005 · 2006 · 2007 · 2008 · 2009 · 2010 · 2011 · 2012Other World cinema Africa Americas Argentina · Brazil · Canada (Quebec) · Chile · Colombia · Cuba · Haiti · Mexico · Paraguay · Peru · Puerto Rico · United States · Uruguay · Venezuela · Latin America · Northern America

Asia Afghanistan · Bangladesh (Bengal) · India (Andhra Pradesh · Assam · Bollywood · Karnataka · Kerala · Marathi · Gujarati · Orissa · Punjab · Tamil Nadu · West Bengal) · Nepal · Pakistan (Azad Kashmir · Karachi · Lahore · Peshawar · Sindh) · Sri Lanka (Jaffna)

Europe Albania · Austria · Belgium · Bosnia and Herzegovina · Bulgaria · Croatia · Czech Republic · Denmark · Estonia · Faroe Islands · Finland · France · Germany · Greece · Hungary · Iceland · Ireland · Italy · Latvia · Lithuania · Luxembourg · Macedonia · Moldova · Montenegro · Netherlands · Norway · Poland · Portugal · Romania · Russia (Russian Empire · Soviet Union) · Serbia · Slovakia · Spain · Sweden · Switzerland · Turkey · Ukraine · United Kingdom (Scotland · Wales) · Yugoslavia

Oceania Australia · Fiji · New Zealand · Samoa

Media of Japan Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.