- Consciousness

-

Consciousness is a term that refers to the relationship between the mind and the world with which it interacts.[1] It has been defined as: subjectivity, awareness, the ability to experience or to feel, wakefulness, having a sense of selfhood, and the executive control system of the mind.[2] Despite the difficulty in definition, many philosophers believe that there is a broadly shared underlying intuition about what consciousness is.[3] As Max Velmans and Susan Schneider wrote in The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness: "Anything that we are aware of at a given moment forms part of our consciousness, making conscious experience at once the most familiar and most mysterious aspect of our lives."[4]

Philosophers since the time of Descartes and Locke have struggled to comprehend the nature of consciousness and pin down its essential properties. Issues of concern in the philosophy of consciousness include whether the concept is fundamentally valid; whether consciousness can ever be explained mechanistically; whether non-human consciousness exists and if so how it can be recognized; how consciousness relates to language; and whether it may ever be possible for computers or robots to be conscious. Perhaps the thorniest issue is whether consciousness can be understood in a way that does not require a dualistic distinction between mental and physical states or properties.

At one time consciousness was viewed with skepticism by many scientists, but in recent years it has become a significant topic of research in psychology and neuroscience. The primary focus is on understanding what it means biologically and psychologically for information to be present in consciousness—that is, on determining the neural and psychological correlates of consciousness. The majority of experimental studies assess consciousness by asking human subjects for a verbal report of their experiences (e.g., "tell me if you notice anything when I do this"). Issues of interest include phenomena such as subliminal perception, blindsight, denial of impairment, and altered states of consciousness produced by psychoactive drugs or spiritual or meditative techniques.

In medicine, consciousness is assessed by observing a patient's arousal and responsiveness, and can be seen as a continuum of states ranging from full alertness and comprehension, through disorientation, delirium, loss of meaningful communication, and finally loss of movement in response to painful stimuli.[5] Issues of practical concern include how the presence of consciousness can be assessed in severely ill, comatose, or anesthetized people, and how to treat conditions in which consciousness is impaired or disrupted.[6]

Contents

Etymology and early history

The origin of the modern concept of consciousness is often attributed to John Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding, published in 1690.[7] Locke defined consciousness as “the perception of what passes in a man’s own mind.”[8] His essay influenced the 18th century view of consciousness, and his definition appeared in Samuel Johnson's celebrated Dictionary (1755).[9]

The earliest English language uses of "conscious" and "consciousness" date back, however, to the 1500s. The English word "conscious" originally derived from the Latin conscius (con- "together" + scire "to know"), but the Latin word did not have the same meaning as our word—it meant knowing with, in other words having joint or common knowledge with another.[10] There were, however, many occurrences in Latin writings of the phrase conscius sibi, which translates literally as "knowing with oneself", or in other words sharing knowledge with oneself about something. This phrase had the figurative meaning of knowing that one knows, as the modern English word "conscious" does. In its earliest uses in the 1500s, the English word "conscious" retained the meaning of the Latin conscius. For example Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan wrote: "Where two, or more men, know of one and the same fact, they are said to be Conscious of it one to another."[11] The Latin phrase conscius sibi, whose meaning was more closely related to the current concept of consciousness, was rendered in English as "conscious to oneself" or "conscious unto oneself". For example, Archbishop Ussher wrote in 1613 of "being so conscious unto myself of my great weakness".[12] Locke's definition from 1690 illustrates that a gradual shift in meaning had taken place.

A related word was conscientia, which primarily means moral conscience. In the literal sense, "conscientia" means knowledge-with, that is, shared knowledge. The word first appears in Latin juridical texts by writers such as Cicero.[13] Here, conscientia is the knowledge that a witness has of the deed of someone else.[14] René Descartes (1596–1650) is generally taken to be the first philosopher to use "conscientia" in a way that does not fit this traditional meaning.[15] Descartes used "conscientia" the way modern speakers would use "conscience." In Search after Truth he says "conscience or internal testimony" (conscientia vel interno testimonio).[16]

In philosophy

The philosophy of mind has given rise to many stances regarding consciousness. Any attempt to impose an organization on them is bound to be somewhat arbitrary. Stuart Sutherland exemplified the difficulty in the entry he wrote for the 1989 version of the Macmillan Dictionary of Psychology:

Consciousness—The having of perceptions, thoughts, and feelings; awareness. The term is impossible to define except in terms that are unintelligible without a grasp of what consciousness means. Many fall into the trap of equating consciousness with self-consciousness—to be conscious it is only necessary to be aware of the external world. Consciousness is a fascinating but elusive phenomenon: it is impossible to specify what it is, what it does, or why it has evolved. Nothing worth reading has been written on it.[17]Most writers on the philosophy of consciousness have been concerned to defend a particular point of view, and have organized their material accordingly. For surveys, the most common approach is to follow a historical path by associating stances with the philosophers who are most most strongly associated with them, for example Descartes, Locke, Kant, etc. The main alternative, followed in the present article, is to organize philosophical stances according to the answers they give to a set of basic questions about the nature and status of consciousness.

Is consciousness a valid concept?

The most compelling argument for the existence of consciousness is that the vast majority of mankind have an overwhelming intuition that there truly is such a thing.[18] Skeptics argue that this intuition, in spite of its compelling quality, is false, either because the concept of consciousness is intrinsically incoherent, or because our intuitions about it are based in illusions. Gilbert Ryle, for example, argued that traditional understanding of consciousness depends on a Cartesian dualist outlook that improperly distinguishes between mind and body, or between mind and world. He proposed that we speak not of minds, bodies, and the world, but of individuals, or persons, acting in the world. Thus, by speaking of 'consciousness' we end up misleading ourselves by thinking that there is any sort of thing as consciousness separated from behavioral and linguistic understandings.[19] More generally, many philosophers and scientists have been unhappy about the difficulty of producing a definition that does not involve circularity or fuzziness.[17]

Is it a single thing?

Many philosophers have argued that consciousness is a unitary concept that is understood intuitively by the majority of people in spite of the difficulty in defining it.[20] Others, though, have argued that the level of disagreement about the meaning of the word indicates that it either means different things to different people, or else is an umbrella term encompassing a variety of distinct meanings with no simple element in common.[21]

Ned Block proposed a distinction between two types of consciousness that he called phenomenal (P-consciousness) and access (A-consciousness).[22] P-consciousness, according to Block, is simply raw experience: it is moving, colored forms, sounds, sensations, emotions and feelings with our bodies and responses at the center. These experiences, considered independently of any impact on behavior, are called qualia. A-consciousness, on the other hand, is the phenomenon whereby information in our minds is accessible for verbal report, reasoning, and the control of behavior. So, when we perceive, information about what we perceive is access conscious; when we introspect, information about our thoughts is access conscious; when we remember, information about the past is access conscious, and so on. Although some philosophers, such as Daniel Dennett, have disputed the validity of this distinction,[23] others have broadly accepted it. David Chalmers has argued that A-consciousness can in principle be understood in mechanistic terms, but that understanding P-consciousness is much more challenging: he calls this the hard problem of consciousness.[24]

Some philosophers believe that Block's two types of consciousness are not the end of the story. William Lycan, for example, argued in his book Consciousness and Experience that at least eight clearly distinct types of consciousness can be identified (organism consciousness; control consciousness; consciousness of; state/event consciousness; reportability; introspective consciousness; subjective consciousness; self-consciousness)—and that even this list omits several more obscure forms.[25]

How does it relate to the physical world?

Illustration of dualism by René Descartes. Inputs are passed by the sensory organs to the pineal gland and from there to the immaterial spirit.

Illustration of dualism by René Descartes. Inputs are passed by the sensory organs to the pineal gland and from there to the immaterial spirit.

The first influential philosopher to discuss this question specifically was Descartes, and the answer he gave is known as Cartesian dualism. Descartes proposed that consciousness resides within an immaterial domain he called res cogitans (the realm of thought), in contrast to the domain of material things which he called res extensa (the realm of extension).[26] He suggested that the interaction between these two domains occurs inside the brain, perhaps in a small midline structure called the pineal gland.[27]

Although it is widely accepted that Descartes explained the problem cogently, few later philosophers have been happy with his solution, and his ideas about the pineal gland have especially been ridiculed.[28] Alternative solutions, however, have been very diverse. They can be divided broadly into two categories: dualist solutions that maintain Descartes's rigid distinction between the realm of consciousness and the realm of matter but give different answers for how the two realms relate to each other; and monist solutions that maintain that there is really only one realm of being, of which consciousness and matter are both aspects. Each of these categories itself contains numerous variants. The two main types of dualism are substance dualism (which holds that the mind is formed of a distinct type of substance not governed by the laws of physics) and property dualism (which holds that the laws of physics are universally valid but cannot be used to explain the mind). The three main types of monism are physicalism (which holds that the mind consists of matter organized in a particular way), idealism (which holds that only thought truly exists and matter is merely an illusion), and neutral monism (which holds that both mind and matter are aspects of a distinct essence that is itself identical to neither of them). There are also, however, a large number of idiosyncratic theories that cannot cleanly be assigned to any of these camps.[29]

Since the dawn of Newtonian science with its vision of simple mechanical principles governing the entire universe, some philosophers have been tempted by the idea that consciousness could be explained in purely physical terms. The first influential writer to propose such an idea explicitly was Julien Offray de La Mettrie, in his book Man a Machine (L'homme machine). His arguments, however, were very abstract.[30] The most influential modern physical theories of consciousness are based on psychology and neuroscience. Theories proposed by neuroscientists such as Gerald Edelman[31] and Antonio Damasio,[32] and by philosophers such as Daniel Dennett,[33] seek to explain consciousness in terms of neural events occurring within the brain. Many other neuroscientists, such as Christof Koch,[34] have explored the neural basis of consciousness without attempting to frame all-encompassing global theories. At the same time, computer scientists working in the field of Artificial Intelligence have pursued the goal of creating digital computer programs that can simulate or embody consciousness.[35]

A few theoretical physicists have argued that classical physics is intrinsically incapable of explaining the holistic aspects of consciousness, but that quantum theory provides the missing ingredients. Several theorists have therefore proposed quantum mind (QM) theories of consciousness. Notable theories falling into this category include the Holonomic brain theory of Karl Pribram and David Bohm, and the Orch-OR theory formulated by Stuart Hameroff and Roger Penrose. Some of these QM theories offer descriptions of phenomenal consciousness, as well as QM interpretations of access consciousness. None of the quantum mechanical theories has been confirmed by experiment, and many scientists and philosophers consider the arguments for an important role of quantum phenomena to be unconvincing.[36]

Why do people believe that other people are conscious?

Many philosophers consider experience to be the essence of consciousness, and believe that experience can only fully be known from the inside, subjectively. But if consciousness is subjective and not visible from the outside, why do the vast majority of people believe that other people are conscious, but rocks and trees are not?[37] This is called the problem of other minds.[38] It is particularly acute for people who believe in the possibility of philosophical zombies, that is, people who think it is possible in principle to have an entity that is physically indistinguishable from a human being and behaves like a human being in every way but nevertheless lacks consciousness.[39]

The most commonly given answer is that we attribute consciousness to other people because we see that they resemble us in appearance and behavior: we reason that if they look like us and act like us, they must be like us in other ways, including having experiences of the sort that we do.[40] There are, however, a variety of problems with that explanation. For one thing, it seems to violate the principle of parsimony, by postulating an invisible entity that is not necessary to explain what we observe.[40] Some philosophers, such as Daniel Dennett in an essay titled The Unimagined Preposterousness of Zombies, argue that people who give this explanation do not really understand what they are saying.[41] More broadly, philosophers who do not accept the possibility of zombies generally believe that consciousness is reflected in behavior (including verbal behavior), and that we attribute consciousness on the basis of behavior. A more straightforward way of saying this is that we attribute experiences to people because of what they can do, including the fact that they can tell us about their experiences.[42]

How can we know whether non-human animals are conscious?

The topic of animal consciousness is beset by a number of difficulties. It poses the problem of other minds in an especially severe form, because animals, lacking language, cannot tell us about their experiences.[43] Also, it is difficult to reason objectively about the question, because a denial that an animal is conscious is often taken to imply that it does not feel, its life has no value, and that harming it is not morally wrong. Descartes, for example, has sometimes been blamed for mistreatment of animals due to the fact that he believed only humans have a non-physical mind.[44] Most people have a strong intuition that some animals, such as dogs, are conscious, while others, such as insects, are not; but the sources of this intuition are not obvious.[43]

Philosophers who consider subjective experience the essence of consciousness also generally believe, as a correlate, that the existence and nature of animal consciousness can never rigorously be known. Thomas Nagel spelled out this point of view in an influential essay titled What Is it Like to Be a Bat?. He said that an organism is conscious "if and only if there is something that it is like to be that organism — something it is like for the organism"; and he argued that no matter how much we know about an animal's brain and behavior, we can never really put ourselves into the mind of the animal and experience its world in the way it does itself.[45] Other thinkers, such as Douglas Hofstadter, dismiss this argument as incoherent.[46] Several psychologists and ethologists have argued for the existence of animal consciousness by describing a range of behaviors that appear to show animals holding beliefs about things they cannot directly perceive — Donald Griffin's 2001 book Animal Minds reviews a substantial portion of the evidence.[47]

Could a machine ever be conscious?

The idea of an artifact made conscious is an ancient theme of mythology, appearing for example in the Greek myth of Pygmalion, who carved a statue that was magically brought to life, and in medieval Jewish stories of the Golem, a magically animated homunculus built of clay.[48] However, the possibility of actually constructing a conscious machine was probably first discussed by Ada Lovelace, in a set of notes written in 1842 about the Analytical Engine invented by Charles Babbage, a precursor (never built) to modern electronic computers. Lovelace was essentially dismissive of the idea that a machine such as the Analytical Engine could think in a humanlike way. She wrote:

It is desirable to guard against the possibility of exaggerated ideas that might arise as to the powers of the Analytical Engine. ... The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform. It can follow analysis; but it has no power of anticipating any analytical relations or truths. Its province is to assist us in making available what we are already acquainted with.[49]One of the most influential contributions to this question was an essay written in 1950 by pioneering computer scientist Alan Turing, titled Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Turing disavowed any interest in terminology, saying that even "Can machines think?" is too loaded with spurious connotations to be meaningful; but he proposed to replace all such questions with a specific operational test, which has become known as the Turing test.[50] To pass the test a computer must be able to imitate a human well enough to fool interrogators. In his essay Turing discussed a variety of possible objections, and presented a counterargument to each of them. The Turing test is commonly cited in discussions of artificial intelligence as a proposed criterion for machine consciousness; it has provoked a great deal of philosophical debate. For example, Daniel Dennett and Douglas Hofstadter argue that anything capable of passing the Turing test is necessarily conscious,[51] while David Chalmers argues that a philosophical zombie could pass the test, yet fail to be conscious.[52]

Some philosophers have argued that it might be possible, at least in principle, for a machine to be conscious, but that this would not just be a matter of executing the right computer program. This viewpoint has most notably been advocated by John Searle, who defended it using a thought experiment that has become known as the Chinese room argument: Suppose the Turing test is conducted in Chinese rather than English, and suppose a computer program successfully passes it. Does the system that is executing the program understand Chinese? Searle's argument is that he could pass the Turing test in Chinese too, by executing exactly the same program as the computer, yet without understanding a word of Chinese. How does Searle know whether he understands Chinese? Understanding a language is not just something you do: it feels like something to understand Chinese (or any language). Understanding is conscious, and therefore there is more to it than merely executing a program, even a Turing-test-passing program.[53]

In the literature concerning artificial consciousness, Searle's essay has been second only to Turing's in the volume of debate it has generated.[53] Searle himself was vague about what extra ingredients it would take to make a machine conscious: all he proposed was that what was needed was "causal powers" of the sort that the brain has and that computers lack. But other thinkers sympathetic to his basic argument have suggested that the necessary (though perhaps still not sufficient) extra conditions may include the ability to pass not just the verbal version of the Turing test, but the robotic version,[54] which requires grounding the robot's words in the robot's sensorimotor capacity to categorize and interact with the things in the world that its words are about, Turing-indistinguishably from a real person. Turing-scale robotics is an empirical branch of research on embodied cognition and situated cognition[55]

Spiritual approaches

To most philosophers, the word "consciousness" connotes the relationship between the mind and the world. To writers on spiritual or religious topics, it frequently connotes the relationship between the mind and God, or the relationship between the mind and deeper truths that are thought to be more fundamental than the physical world. Krishna consciousness, for example, is a term used to mean an intimate linkage between the mind of a worshipper and the god Krishna.[56] The mystical psychiatrist Richard Maurice Bucke distinguished between three types of consciousness: Simple Consciousness, awareness of the body, possessed by many animals; Self Consciousness, awareness of being aware, possessed only by humans; and Cosmic Consciousness, awareness of the life and order of the universe, possessed only by humans who are enlightened.[57] Many more examples could be given. The most thorough account of the spiritual approach may be Ken Wilber's book The Spectrum of Consciousness, a comparison of western and eastern ways of thinking about the mind. Wilber described consciousness as a spectrum with ordinary awareness at one end, and more profound types of awareness at higher levels.[58]

Scientific approaches

For many decades, consciousness as a research topic was avoided by the majority of mainstream scientists, because of a general feeling that a phenomenon defined in subjective terms could not properly be studied using objective experimental methods.[59] Starting in the 1980s, though, an expanding community of neuroscientists and psychologists have associated themselves with a field called Consciousness Studies, giving rise to a stream of experimental work published in journals such as Consciousness and Cognition, and methodological work published in journals such as the Journal of Consciousness Studies, along with regular conferences organized by groups such as the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness.[60]

Modern scientific investigations into consciousness are based on psychological experiments (including, for example, the investigation of priming effects using subliminal stimuli), and on case studies of alterations in consciousness produced by trauma, illness, or drugs. Broadly viewed, scientific approaches are based on two core concepts. The first identifies the content of consciousness with the experiences that are reported by human subjects; the second makes use of the concept of consciousness that has been developed by neurologists and other medical professionals who deal with patients whose behavior is impaired. In either case, the ultimate goals are to develop techniques for assessing consciousness objectively in humans as well as other animals, and to understand the neural and psychological mechanisms that underlie it.[34]

Measurement

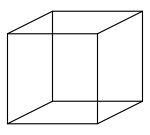

Experimental research on consciousness presents special difficulties, due to the lack of a universally accepted operational definition. In the majority of experiments that are specifically about consciousness, the subjects are human, and the criterion that is used is verbal report: in other words, subjects are asked to describe their experiences, and their descriptions are treated as observations of the contents of consciousness.[61] For example, subjects who stare continuously at a Necker Cube usually report that they experience it "flipping" between two 3D configurations, even though the stimulus itself remains the same.[62] The objective is to understand the relationship between the conscious awareness of stimuli (as indicated by verbal report) and the effects the stimuli have on brain activity and behavior. In several paradigms, such as the technique of response priming, the behavior of subjects is clearly influenced by stimuli for which they report no awareness.[63]

Verbal report is widely considered to be the most reliable indicator of consciousness, but it raises a number of issues.[64] For one thing, if verbal reports are treated as observations, akin to observations in other branches of science, then the possibility arises that they may contain errors—but it is difficult to make sense of the idea that subjects could be wrong about their own experiences, and even more difficult to see how such an error could be detected.[65] Daniel Dennett has argued for an approach he calls heterophenomenology, which means treating verbal reports as stories that may or may not be true, but his ideas about how to do this have not been widely adopted.[66] Another issue with verbal report as a criterion is that it restricts the field of study to humans who have language: this approach cannot be used to study consciousness in other species, pre-linguistic children, or people with types of brain damage that impair language. As a third issue, philosophers who dispute the validity of the Turing test may feel that it is possible, at least in principle, for verbal report to be dissociated from consciousness entirely: a philosophical zombie may give detailed verbal reports of awareness in the absence of any genuine awareness.[67]

Although verbal report is in practice the "gold standard" for ascribing consciousness, it is not the only possible criterion.[64] In medicine, consciousness is assessed as a combination of verbal behavior, arousal, brain activity and purposeful movement. The last three of these can be used as indicators of consciousness when verbal behavior is absent.[68] The scientific literature regarding the neural bases of arousal and purposeful movement is very extensive. Their reliability as indicators of consciousness is disputed, however, due to numerous studies showing that alert human subjects can be induced to behave purposefully in a variety of ways in spite of reporting a complete lack of awareness.[63] Studies of the neuroscience of free will have also shown that the experiences that people report when they behave purposefully sometimes do not correspond to their actual behaviors or to the patterns of electrical activity recorded from their brains.[69]

Another approach applies specifically to the study of self-awareness, that is, the ability to distinguish oneself from others. In the 1970s Gordon Gallup developed an operational test for self-awareness, known as the mirror test. The test examines whether animals are able to differentiate between seeing themselves in a mirror versus seeing other animals. The classic example involves placing a spot of coloring on the skin or fur near the individual's forehead and seeing if they attempt to remove it or at least touch the spot, thus indicating that they recognize that the individual they are seeing in the mirror is themselves.[70] Humans (older than 18 months) and other great apes, bottlenose dolphins, pigeons, and elephants have all been observed to pass this test.[71]

Neural correlates

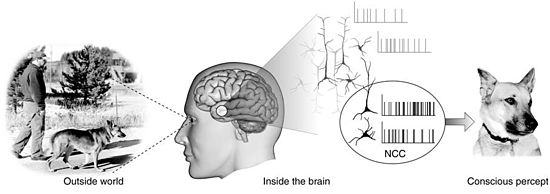

A major part of the scientific literature on consciousness consists of studies that examine the relationship between the experiences reported by subjects and the activity that simultaneously takes place in their brains—that is, studies of the neural correlates of consciousness. The hope is to find that activity in a particular part of the brain, or a particular pattern of global brain activity, will be strongly predictive of conscious awareness. Several brain imaging techniques, such as EEG and fMRI, have been used for physical measures of brain activity in these studies.[72]

One idea that has drawn attention for several decades is that consciousness is associated with high-frequency (gamma band) EEG oscillations. This idea arose from proposals in the 1980s, by Christof von der Malsburg and Wolf Singer, that gamma oscillations could solve the so-called binding problem, by linking information represented in different parts of the brain into a unified experience.[73] Rodolfo Llinás, for example, proposed that consciousness results from recurrent thalamo-cortical resonance where the specific thalamocortical systems (content) and the non-specific (centromedial thalamus) thalamocortical systems (context) interact in the gamma band frequency via temporal coincidence.[74]

A number of studies have shown that activity in primary sensory areas of the brain is not sufficient to produce consciousness: it is possible for subjects to report a lack of awareness even when areas such as the primary visual cortex show clear electrical responses to a stimulus.[75] Higher brain areas are seen as more promising, especially the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in a range of higher cognitive functions collectively known as executive functions. There is substantial evidence that a "top-down" flow of neural activity (i.e., activity propagating from the frontal cortex to sensory areas) is more predictive of conscious awareness than a "bottom-up" flow of activity.[76] The prefrontal cortex is not the only candidate area, however: studies by Nikos Logothetis and his colleagues have shown, for example, that visually responsive neurons in parts of the temporal lobe reflect the visual perception in the situation when conflicting visual images are presented to different eyes (i.e., bistable percepts during binocular rivalry).[77]

Biological function and evolution

Regarding the primary function of conscious processing, a recurring idea in recent theories is that phenomenal states somehow integrate neural activities and information-processing that would otherwise be independent.[78] This has been called the integration consensus. However, it remains unspecified which kinds of information are integrated in a conscious manner and which kinds can be integrated without consciousness. Nor is it explained what specific causal role conscious integration plays, nor why the same functionality cannot be achieved without consciousness. Obviously not all kinds of information are capable of being disseminated consciously (e.g., neural activity related to vegetative functions, reflexes, unconscious motor programs, low-level perceptual analyses, etc.) and many kinds of information can be disseminated and combined with other kinds without consciousness, as in intersensory interactions such as the ventriloquism effect. Hence it remains unclear why any of it is conscious.[79]

As noted earlier, even among writers who consider consciousness to be a well-defined thing, there is widespread dispute about which animals other than humans can be said to possess it.[80] Thus, any examination of the evolution of consciousness is faced with great difficulties. Nevertheless, some writers have argued that consciousness can be viewed from the standpoint of evolutionary biology as an adaptation in the sense of a trait that increases fitness.[81] In his paper "Evolution of consciousness," John Eccles argued that special anatomical and physical properties of the mammalian cerebral cortex gave rise to consciousness.[82] Bernard Baars proposed that once in place, this "recursive" circuitry may have provided a basis for the subsequent development of many of the functions that consciousness facilitates in higher organisms.[83]

Other philosophers, however, have suggested that consciousness would not be necessary for any functional advantage in evolutionary processes.[84] No one has given a causal explanation, they argue, of why it would not be possible for a functionally equivalent non-conscious organism (i.e., a philosophical zombie) to achieve the very same survival advantages as a conscious organism. If evolutionary processes are blind to the difference between function F being performed by conscious organism O and non-conscious organism O*, it is unclear what adaptive advantage consciousness could provide.[85]

States of consciousness

There are some states in which consciousness seems to be abolished, including sleep, coma, and death. There are also a variety of circumstances that can change the relationship between the mind and the world in less drastic ways, producing what are known as altered states of consciousness. Some altered states occur naturally; others can be produced by drugs or brain damage.[86]

The two most widely accepted altered states are sleep and dreaming. Although dream sleep and non-dream sleep appear very similar to an outside observer, each is associated with a distinct pattern of brain activity, metabolic activity, and eye movement; each is also associated with a distinct pattern of experience and cognition. During ordinary non-dream sleep, people who are awakened report only vague and sketchy thoughts, and their experiences do not cohere into a continuous narrative. During dream sleep, in contrast, people who are awakened report rich and detailed experiences in which events form a continuous progression, which may however be interrupted by bizarre or fantastic intrusions. Thought processes during the dream state frequently show a high level of irrationality. Both dream and non-dream states are associated with severe disruption of memory: it usually disappears in seconds during the non-dream state, and in minutes after awakening from a dream unless actively refreshed.[87]

A variety of psychoactive drugs have notable effects on consciousness. These range from a simple dulling of awareness produced by sedatives, to increases in the intensity of sensory qualities produced by stimulants, cannabis, or most notably by the class of drugs known as psychedelics.[86] LSD, mescaline, psilocybin, and others in this group can produce major distortions of perception, including hallucinations; some users even describe their drug-induced experiences as mystical or spiritual in quality. The brain mechanisms underlying these effects are not well understood, but there is substantial evidence that alterations in the brain system that uses the chemical neurotransmitter serotonin play an essential role.[88]

There has been some research into physiological changes in yogis and people who practise various techniques of meditation. Some research with brain waves during meditation has differences between those corresponding to ordinary relaxation and those corresponding to meditation. It has been disputed, however, whether there is enough evidence to count these as physiologically distinct states of consciousness.[89]

The most extensive study of the characteristics of altered states of consciousness was made by psychologist Charles Tart in the 1960s and 1970s. Tart analyzed a state of consciousness as made up of a number of component processes, including exteroception (sensing the external world); interoception (sensing the body); input-processing (seeing meaning); emotions; memory; time sense; sense of identity; evaluation and cognitive processing; motor output; and interaction with the environment.[90] Each of these, in his view, could be altered in multiple ways by drugs or other manipulations. The components that Tart identified have not, however, been validated by empirical studies. Research in this area has not yet reached firm conclusions, but a recent questionnaire-based study identified eleven significant factors contributing to drug-induced states of consciousness: experience of unity; spiritual experience; blissful state; insightfulness; disembodiment; impaired control and cognition; anxiety; complex imagery; elementary imagery; audio-visual synesthesia; and changed meaning of percepts.[91]

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is a method of inquiry that attempts to examine the structure of consciousness in its own right, putting aside problems regarding the relationship of consciousness to the physical world. This approach was first proposed by the philosopher Edmund Husserl, and later elaborated by other philosophers and scientists.[92] Husserl's original concept gave rise to two distinct lines of inquiry, in philosophy and psychology. In philosophy, phenomenology has largely been devoted to fundamental metaphysical questions, such as the nature of intentionality ("aboutness"). In psychology, phenomenology largely has meant attempting to investigate consciousness using the method of introspection, which means looking into one's own mind and reporting what one observes. This method fell into disrepute in the early twentieth century because of grave doubts about its reliability, but has been rehabilitated to some degree, especially when used in combination with techniques for examining brain activity.[93]

Neon color spreading effect. The apparent bluish tinge of the white areas inside the circle is an illusion.

Neon color spreading effect. The apparent bluish tinge of the white areas inside the circle is an illusion.

Introspectively, the world of conscious experience seems to have considerable structure. Immanuel Kant asserted that the world as we perceive it is organized according to a set of fundamental "intuitions", which include object (we perceive the world as a set of distinct things); shape; quality (color, warmth, etc.); space (distance, direction, and location); and time.[94] Some of these constructs, such as space and time, correspond to the way the world is structured by the laws of physics; for others the correspondence is not as clear. Understanding the physical basis of qualities, such as redness or pain, has been particularly challenging. David Chalmers has called this the hard problem of consciousness.[24] Some philosophers have argued that it is intrinsically unsolvable, because qualities ("qualia") are ineffable; that is, they are "raw feels", incapable of being analyzed into component processes.[95] Most psychologists and neuroscientists have not accepted these arguments — nevertheless it is clear that the relationship between a physical entity such as light and a perceptual quality such as color is extraordinarily complex and indirect, as demonstrated by a variety of optical illusions such as neon color spreading.[96]

In neuroscience, a great deal of effort has gone into investigating how the perceived world of conscious awareness is constructed inside the brain. The process is generally thought to involve two primary mechanisms: (1) hierarchical processing of sensory inputs, (2) memory. Signals arising from sensory organs are transmitted to the brain and then processed in a series of stages, which extract multiple types of information from the raw input. In the visual system, for example, sensory signals from the eyes are transmitted to the thalamus and then to the primary visual cortex; inside the cerebral cortex they are sent to areas that extract features such as three-dimensional structure, shape, color, and motion.[97] Memory comes into play in at least two ways. First, it allows sensory information to be evaluated in the context of previous experience. Second, and even more importantly, working memory allows information to be integrated over time so that it can generate a stable representation of the world—Gerald Edelman expressed this point vividly by titling one of his books about consciousness The Remembered Present.[98]

Despite the large amount of information available, the most important aspects of perception remain mysterious. A great deal is known about low-level signal processing in sensory systems, but the ways by which sensory systems interact with each other, with "executive" systems in the frontal cortex, and with the language system are very incompletely understood. At a deeper level, there are still basic conceptual issues that remain unresolved.[97] Many scientists have found it difficult to reconcile the fact that information is distributed across multiple brain areas with the apparent unity of consciousness: this is one aspect of the so-called binding problem.[99] There are also some scientists who have expressed grave reservations about the idea that the brain forms representations of the outside world at all: influential members of this group include psychologist J. J. Gibson and roboticist Rodney Brooks, who both argued in favor of "intelligence without representation".[100]

Medical aspects

The medical approach to consciousness is practically oriented. It derives from a need to treat people whose brain function has been impaired as a result of disease, brain damage, toxins, or drugs. In medicine, conceptual distinctions are considered useful to the degree that they can help to guide treatments. Whereas the philosophical approach to consciousness focuses on its fundamental nature and its contents, the medical approach focuses on the amount of consciousness a person has: in medicine, consciousness is assessed as a "level" ranging from coma and brain death at the low end, to full alertness and purposeful responsiveness at the high end.[101]

Consciousness is of concern to patients and physicians, especially neurologists and anesthesiologists. Patients may suffer from disorders of consciousness, or may need to be anesthetized for a surgical procedure. Physicians may perform consciousness-related interventions such as instructing the patient to sleep, administering general anesthesia, or inducing medical coma.[101] Also, bioethicists may be concerned with the ethical implications of consciousness in medical cases of patients such as Karen Ann Quinlan,[102] while neuroscientists may study patients with impaired consciousness in hopes of gaining information about how the brain works.[103]

Assessment

In medicine, consciousness is examined using a set of procedures known as neuropsychological assessment.[68] There are two commonly used methods for assessing the level of consciousness of a patient: a simple procedure that requires minimal training, and a more complex procedure that requires substantial expertise. The simple procedure begins by asking whether the patient is able to move and react to physical stimuli. If so, the next question is whether the patient can respond in a meaningful way to questions and commands. If so, the patient is asked for name, current location, and current day and time. A patient who can answer all of these questions is said to be "oriented times three" (sometimes denoted "Ox3" on a medical chart), and is usually considered fully conscious.[104]

The more complex procedure is known as a neurological examination, and is usually carried out by a neurologist in a hospital setting. A formal neurological examination runs through a precisely delineated series of tests, beginning with tests for basic sensorimotor reflexes, and culminating with tests for sophisticated use of language. The outcome may be summarized using the Glasgow Coma Scale, which yields a number in the range 3—15, with a score of 3 indicating brain death (the lowest defined level of consciousness), and 15 indicating full consciousness. The Glasgow Coma Scale has three subscales, measuring the best motor response (ranging from "no motor response" to "obeys commands"), the best eye response (ranging from "no eye opening" to "eyes opening spontaneously") and the best verbal response (ranging from "no verbal response" to "fully oriented"). There is also a simpler pediatric version of the scale, for children too young to be able to use language.[101]

Disorders of consciousness

Medical conditions that inhibit consciousness are considered disorders of consciousness.[105] This category generally includes minimally conscious state and persistent vegetative state, but sometimes also includes the less severe locked-in syndrome and more severe chronic coma.[105][106] Differential diagnosis of these disorders is an active area of biomedical research.[107][108][109] Finally, brain death results in an irreversible disruption of consciousness.[105] While other conditions may cause a moderate deterioration (e.g., dementia and delirium) or transient interruption (e.g., grand mal and petit mal seizures) of consciousness, they are not included in this category.

Disorder Description Locked-in syndrome The patient has awareness, sleep-wake cycles, and meaningful behavior (viz., eye-movement), but is isolated due to quadriplegia and pseudobulbar palsy. Minimally conscious state The patient has intermittent periods of awareness and wakefulness and displays some meaningful behavior. Persistent vegetative state The patient has sleep-wake cycles, but lacks awareness and only displays reflexive and non-purposeful behavior. Chronic coma The patient lacks awareness and sleep-wake cycles and only displays reflexive behavior. Brain death The patient lacks awareness, sleep-wake cycles, and behavior. Anosognosia

One of the most striking disorders of consciousness goes by the name anosognosia, a Greek-derived term meaning unawareness of disease. This is a condition in which patients are disabled in some way, most commonly as a result of a stroke, but either misunderstand the nature of the problem or deny that there is anything wrong with them.[110] The most frequently occurring form is seen in people who have experienced a stroke damaging the parietal lobe in the right hemisphere of the brain, giving rise to a syndrome known as hemispatial neglect, characterized by an inability to direct action or attention toward objects located to the right with respect to their bodies. Patients with hemispatial neglect are often paralyzed on the right side of the body, but sometimes deny being unable to move. When questioned about the obvious problem, the patient may avoid giving a direct answer, or may give an explanation that doesn't make sense. Patients with hemispatial neglect may also fail to recognize paralyzed parts of their bodies: one frequently mentioned case is of a man who repeatedly tried to throw his own paralyzed right leg out of the bed he was lying in, and when asked what he was doing, complained that somebody had put a dead leg into the bed with him. An even more striking type of anosognosia is Anton–Babinski syndrome, a rarely occurring condition in which patients become blind but claim to be able to see normally, and persist in this claim in spite of all evidence to the contrary.[111]

The stream of consciousness

William James is usually credited with popularizing the idea that human consciousness flows like a stream, in his Principles of Psychology of 1890. According to James, the "stream of thought" is governed by five characteristics: "(1) Every thought tends to be part of a personal consciousness. (2) Within each personal consciousness thought is always changing. (3) Within each personal consciousness thought is sensibly continuous. (4) It always appears to deal with objects independent of itself. (5) It is interested in some parts of these objects to the exclusion of others".[112] A similar concept appears in Buddhist philosophy, expressed by the Sanskrit term Citta-saṃtāna, which is usually translated as mindstream or "mental continuum". In the Buddhist view, though, the "mindstream" is viewed primarily as a source of noise that distracts attention from a changeless underlying reality.[113]

In the west, the primary impact of the idea has been on literature rather than science: stream of consciousness as a narrative mode means writing in a way that attempts to portray the moment-to-moment thoughts and experiences of a character. This technique perhaps had its beginnings in the monologues of Shakespeare's plays, and reached its fullest development in the novels of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, although it has also been used by many other noted writers.[114]

Here for example is a passage from Joyce's Ulysses about the thoughts of Molly Bloom:

Yes because he never did a thing like that before as ask to get his breakfast in bed with a couple of eggs since the City Arms hotel when he used to be pretending to be laid up with a sick voice doing his highness to make himself interesting for that old faggot Mrs Riordan that he thought he had a great leg of and she never left us a farthing all for masses for herself and her soul greatest miser ever was actually afraid to lay out 4d for her methylated spirit telling me all her ailments she had too much old chat in her about politics and earthquakes and the end of the world let us have a bit of fun first God help the world if all the women were her sort down on bathingsuits and lownecks of course nobody wanted her to wear them I suppose she was pious because no man would look at her twice I hope Ill never be like her a wonder she didnt want us to cover our faces but she was a welleducated woman certainly and her gabby talk about Mr Riordan here and Mr Riordan there I suppose he was glad to get shut of her.[115]See also

- Blindsight

- Causality

- Cognitive neuroscience

- Cognitive psychology

- Explanation

- Explanatory gap

- Functionalism (philosophy of mind)

- Hard problem of consciousness

- Merkwelt

- Mind

- Mind-body problem

- Mirror neuron

- Neuropsychological assessment

- Neuropsychology

- Phenomenology

- Philosophical zombie

- Philosophy of mind

- Problem of other minds

- Reverse engineering

- Sentience

- Solipsism

- Turing test

References

- ^ Robert van Gulick (2004). "Consciousness". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/consciousness/.

- ^ Farthing G (1992). The Psychology of Consciousness. Prentice Hall. ISBN 9780137286683.

- ^ John Searle (2005). "Consciousness". In Honderich T. The Oxford companion to philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199264797.

- ^ Susan Schneider and Max Velmans (2008). "Introduction". In Max Velmans, Susan Schneider. The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness. Wiley. ISBN 9780470751459.

- ^ Güven Güzeldere (1997). Ned Block, Owen Flanagan, Güven Güzeldere. ed. The Nature of Consciousness: Philosophical debates. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 1–67.

- ^ J. J. Fins, N. D. Schiff, and K. M. Foley (2007). "Late recovery from the minimally conscious state: ethical and policy implications". Neurology 68: 304–307. PMID 17242341.

- ^ Locke, John. "An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (Chapter XXVII)". Australia: University of Adelaide. http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/l/locke/john/l81u/B2.27.html. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ "Science & Technology: consciousness". Encyclopedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/133274/consciousness. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ Samuel Johnson (1756). A Dictionary of the English Language. Knapton. http://books.google.com/books?id=fcVEAAAAcAAJ.

- ^ C. S. Lewis (1990). "Ch. 8: Conscience and conscious". Studies in words. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521398312.

- ^ Thomas Hobbes (1904). Leviathan: or, The Matter, Forme & Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civill. University Press. p. 39. http://books.google.com/books?id=2oc6AAAAMAAJ.

- ^ James Ussher, Charles Richard Elrington (1613). The whole works, Volume 2. Hodges and Smith. p. 417.

- ^ James Hastings and John A. Selbie (2003). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics Part 7. Kessinger Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 0766136779.

- ^ G. Melenaar. Mnemosyne, Fourth Series. 22. Brill. pp. 170–180.

- ^ Boris Hennig (2007). "Cartesian Conscientia". British Journal for the History of Philosophy 15: 455–484.

- ^ Sara Heinämaa (2007). Consciousness: from perception to reflection in the history of philosophy. Springer. pp. 205–206. ISBN 9781402060816.

- ^ a b Stuart Sutherland (1989). "Consciousness". Macmillan Dictionary of Psychology. Macmillan. ISBN 9780333388297.

- ^ Justin Sytsma and Edouard Machery (2010). "Two conceptions of subjective experience". Philosophical Studies 151: 299–327. doi:10.1007/s11098-009-9439-x.

- ^ Gilbert Ryle (1949). The Concept of Mind. University of Chicago Press. pp. 156–163. ISBN 9780226732961.

- ^ Michael V. Antony (2001). "Is consciousness ambiguous?". Journal of Consciousness Studies 8: 19–44.

- ^ Max Velmans (2009). "How to define consciousness—and how not to define consciousness". Journal of Consciousness Studies 16: 139–156.

- ^ Ned Block (1998). "On a confusion about a function of consciousness". In N. Block, O. Flanagan, G. Guzeldere. The Nature of Consciousness: Philosophical Debates. MIT Press. pp. 375–415. ISBN 9780262522106. http://cogprints.org/231/1/199712004.html.

- ^ Daniel Dennett (2004). Consciousness Explained. Penguin. pp. 375. ISBN 09713990376.

- ^ a b David Chalmers (1995). "Facing up to the problem of consciousness". Journal of Consciousness Studies 2: 200–219. http://www.imprint.co.uk/chalmers.html.

- ^ William Lycan (1996). Consciousness and Experience. MIT Press. pp. 1–4. ISBN 9780262121972.

- ^ Dy, Jr., Manuel B. (2001). Philosophy of Man: selected readings. Goodwill Trading Co.. p. 97. ISBN 971-12-0245-X.

- ^ "Descartes and the Pineal Gland". Stanford University. November 5, 2008. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pineal-gland/. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Gert-Jan Lokhorst. "Descartes and the pineal gland". In Edward N. Zalta. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2011 Edition). http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2011/entries/pineal-gland/.

- ^ William Jaworski (2011). Philosophy of Mind: A Comprehensive Introduction. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 5–11. ISBN 9781444333671.

- ^ Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1996). Ann Thomson. ed. Machine man and other writings. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521478496.

- ^ Gerald Edelman (1993). Bright Air, Brilliant Fire: On the Matter of the Mind. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465007646.

- ^ Antonio Damasio (1999). The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. New York: Harcourt Press. ISBN 9780156010757.

- ^ Daniel Dennett (1991). Consciousness Explained. Boston: Little & Company. ISBN 9780316180665.

- ^ a b Christof Koch (2004). The Quest for Consciousness. Englewood CO: Roberts & Company. ISBN 9780974707709.

- ^ Stuart J. Russell, Peter Norvig (2010). "Ch. 26: Philosophical foundations". Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. Prentice Hall. ISBN 9780136042594.

- ^ John Searle (1997). The Mystery of Consciousness. The New York Review of Books. pp. 53–88. ISBN 9780940322066.

- ^ Knobe J (2008). "Can a Robot, an Insect or God Be Aware?". Scientific American: Mind. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=can-a-robot-an-insect-or.

- ^ Alec Hyslop (1995). Other Minds. Springer. pp. 5–14. ISBN 9780792332459.

- ^ Robert Kirk. "Zombies". In Edward N. Zalta. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2009 Edition). http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2009/entries/zombies.

- ^ a b Alec Hyslop (1995). "The analogical inference to other minds". Other Minds. Springer. pp. 41–70. ISBN 9780792332459.

- ^ Daniel Dennett (1995). "The unimagined preposterousness of zombies". Journal of Consciousness Studies 2: 322–325.

- ^ Stevan Harnad (1995). "Why and how we are not zombies". Journal of Consciousness Studies 1: 164–167.

- ^ a b Colin Allen. "Animal consciousness". In Edward N. Zalta. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2011 Edition). http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2011/entries/consciousness-animal/.

- ^ Peter Carruthers (1999). "Sympathy and subjectivity". Australasian Journal of Philosophy 77: 465–482.

- ^ Thomas Nagel (1991). "Ch. 12 What is it like to be a bat?". Mortal Questions. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521406765.

- ^ Douglas Hofstadter (1981). "Reflections on What Is It Like to Be a Bat?". In Douglas Hofstadter and Daniel Dennett. The Mind's I. Basic Books. pp. 403–414. ISBN 046504624.

- ^ Donald Griffin (2001). Animal Minds: Beyond Cognition to Consciousness. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226308654.

- ^ Moshe Idel (1990). Golem: Jewish Magical and Mystical Traditions on the Artificial Anthropoid. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791401606. Note: In many stories the Golem was mindless, but some gave it emotions or thoughts.

- ^ Ada Lovelace. "Sketch of The Analytical Engine, Note G". http://www.fourmilab.ch/babbage/sketch.html.

- ^ Stuart Shieber (2004). The Turing Test : Verbal Behavior as the Hallmark of Intelligence. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262692939.

- ^ Daniel Dennett and Douglas Hofstadter (1985). The Mind's I. Basic Books. ISBN 9780553345841.

- ^ David Chalmers (1997). The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019511789.

- ^ a b John Searle et al. (1980). "Minds, brains, and programs". Behavioral and Brain Sciences 3: 417–457. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00005756.

- ^ Graham Oppy and David Dowe (2011). "The Turing test". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2011 Edition). http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2011/entries/turing-test.

- ^ Margaret Wilson (2002). "Six views of embodied cognition". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 9: 625–636. http://philosophy.wisc.edu/shapiro/PHIL951/951articles/wilson.htm.

- ^ Lynne Gibson (2002). Modern World Religions: Hinduism. Heinemann Educational Publishers. pp. 2–4. ISBN 0435336193.

- ^ Richard Maurice Bucke (1905). Cosmic Consciousness: A Study in the Evolution of the Human Mind. Innes & Sons. pp. 1–2. http://books.google.com/books?id=gxRWAAAAMAAJ.

- ^ Ken Wilber (2002). The Spectrum of Consciousness. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.. pp. 3–16. ISBN 9788120818484.

- ^ Horst Hendriks-Jansen (1996). Catching ourselves in the act: situated activity, interactive emergence, evolution, and human thought. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. p. 114. ISBN 0262082462.

- ^ Stuart Hameroff, Alfred Kaszniak, David Chalmers (1999). "Preface". Toward a Science of Consciousness III: The Third Tucson Discussions and Debates. MIT Press. pp. xix–xx. ISBN 9780262581813.

- ^ Bernard Baars (1993). A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness. Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–18. ISBN 9780521427432.

- ^ Paul Rooks and Jane Wilson (2000). Perception: Theory, Development, and Organization. Psychology Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9780415190947.

- ^ a b Thomas Schmidt and Dirk Vorberg (2006). "Criteria for unconscious cognition: Three types of dissociation". Perception and Psychophysics 68: 489–504.

- ^ a b Arnaud Destrebecqz and Philippe Peigneux (2006). "Methods for studying unconscious learning". In Steven Laureys. The Boundaries of Consciousness: Neurobiology and Neuropathology. Elsevier. pp. 69–80. ISBN 9780444528766.

- ^ Daniel Dennett (1992). "Quining qualia". In A. Marcel and E. Bisiach. Consciousness in Modern Science. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198522379. http://cogprints.org/254/. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ^ Daniel Dennett (2003). "Who’s on first? Heterophenomenology explained". Journal of Consciousness Studies 10: 19–30.

- ^ David Chalmers (1996). "Ch. 3: Can consciousness be reductively explained?". The Conscious Mind. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195117899.

- ^ a b J. T. Giacino, C. M. Smart (2007). "Recent advances in behavioral assessment of individuals with disorders of consciousness". Current Opinion in Neurology 20: 614–619. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282f189ef. PMID 17992078.

- ^ Patrick Haggard (2008). "Human volition: towards a neuroscience of will". Nature Reviews Neuroscience 9: 934–946. PMID 19020512.

- ^ Gordon Gallup (1970). "Chimpanzees: Self recognition". Science 167: 86–87. doi:10.1126/science.167.3914.86. PMID 4982211.

- ^ David Edelman and Anil Seth (2009). "Animal consciousness: a synthetic approach". Trends in Neurosciences 32: 476–484. PMID 19716185.

- ^ Christof Koch (2004). The Quest for Consciousness. Englewood CO: Roberts & Company. pp. 16–19. ISBN 9780974707709.

- ^ Wolf Singer. "Binding by synchrony". Scholarpedia. http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Binding_by_synchrony. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ^ Rodolfo Llinás (2002). I of the Vortex. From Neurons to Self. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262621632.

- ^ Koch, The Quest for Consciousness, pp. 105–116

- ^ Francis Crick and Christof Koch (2003). "A framework for consciousness" (PDF). Nature Neuroscience 6: 119–126. doi:10.1038/nn0203-119. PMID 12555104. http://papers.klab.caltech.edu/29/1/438.pdf.

- ^ Koch, The Quest for Consciousness, pp. 269–286

- ^ Bernard Baars. "The conscious access hypothesis: Origins and recent evidence". Trends in Cognitive Sciences 6: 47–52. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01819-2. PMID 11849615.

- ^ Ezequiel Morsella and John A. Bargh (2007). "Supracortical consciousness: Insights from temporal dynamics, processing-content, and olfaction". Behavioral and Brain Sciences 30: 100. PMC 2729140. PMID 19696906. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2729140.

- ^ S. Budiansky (1998). If a Lion Could Talk: Animal Intelligence and the Evolution of Consciousness. The Free Press. ISBN 9780684837109.

- ^ S. Nichols, T. Grantham (2000). "Adaptive Complexity and Phenomenal Consciousness". Philosophy of Science 67: 648–670.

- ^ John Eccles (1992). "Evolution of consciousness". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89: 7320–7324. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.16.7320. PMC 49701. PMID 1502142. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=49701.

- ^ Bernard Baars (1993). A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521427432.

- ^ Owen Flanagan and T. W. Polger (1995). "Zombies and the function of consciousness". Journal of Consciousness Studies 2: 313–321.

- ^ Stevan Harnad (2002). "Turing indistinguishability and the Blind Watchmaker". In J. H. Fetzer. Consciousness Evolving. John Benjamins. http://cogprints.org/1615. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ^ a b Dieter Vaitl et al. (2005). "Psychobiology of altered states of consciousness". Psychological Bulletin 131: 98–127.

- ^ J. Allan Hobson, Edward F. Pace-Schott, and Robert Stickgold (2003). "Dreaming and the brain: Toward a cognitive neuroscience of conscious states". In Edward F. Pace-Schott, Mark Solms, Mark Blagrove, Stevan Harnad. Sleep and Dreaming: Scientific Advances and Reconsiderations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521008693.

- ^ Michael Lyvers (2003). "The neurochemistry of psychedelic experiences" (PDF). ePublications@bond. http://epublications.bond.edu.au/hss_pubs/10.

- ^ M. Murphy, S. Donovan, and E. Taylor (1997). The Physical and Psychological Effects of Meditation: A Review of Contemporary Research With a Comprehensive Bibliography, 1931-1996. Institute of Noetic Sciences.

- ^ Charles Tart (2001). "Ch. 2: The components of consciousness". States of Consciousness. IUniverse.com. ISBN 9780595151967. http://www.psychedelic-library.org/soc2.htm. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- ^ E. Studerus, A. Gamma, and F. X. Vollenweider (2010). "Psychometric evaluation of the altered states of consciousness rating scale (OAV)". PLoS ONE 8. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012412. PMC 2930851. PMID 20824211. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2930851.

- ^ Robert Sokolowski (2000). Introduction to Phenomenology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 211–227. ISBN 9780521667920.

- ^ K. Anders Ericsson (2003). "Valid and non-reactive verbalization of thoughts during performance of tasks: towards a solution to the central problems of introspection as a source of scientific evidence". In Anthony Jack, Andreas Roepstorff. Trusting the Subject?: The Use of Introspective Evidence in Cognitive Science, Volume 1. Imprint Academic. pp. 1–18. ISBN 9780907845560.

- ^ Andrew Brook. "Kant's view of the mind and consciousness of self". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-mind/#3.2.1. Note: translating Kant's terminology into English is often difficult.

- ^ Joseph Levine (1998). "On leaving out what it's like". In N. Block, O. Flanagan, G. Guzeldere. The Nature of Consciousness: Philosophical Debates. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262522106.

- ^ Steven K. Shevell (2003). "Color appearance". In Steven K. Shevell. The Science of Color. Elsevier. pp. 149–190. ISBN 9780444512512.

- ^ a b M. R. Bennett and Peter Michael Stephan Hacker (2003). Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 121–147. ISBN 9781405108386.

- ^ Gerald Edelman (1989). The Remembered Present: A Biological Theory of Consciousness. Basic Books. pp. 109–118. ISBN 9780465069101.

- ^ Koch, The Quest for Consciousness, pp. 167–170

- ^ Rodney Brooks (1991). "Intelligence without representation". Artificial Intelligence 47: 139–159. doi:10.1016/0004-3702(91)90053-M.

- ^ a b c Hal Blumenfeld (2009). "The neurological examination of consciousness". In Steven Laureys, Guilio Tononi. The Neurology of Consciousness: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropathology. Academic Press. ISBN 9780123741684.

- ^ Kinney HC, Korein J, Panigrahy A, Dikkes P, Goode R (26 May 1994). "Neuropathological findings in the brain of Karen Ann Quinlan -- the role of the thalamus in the persistent vegetative state". N Engl J Med 330 (21): 1469–1475. doi:10.1056/NEJM199405263302101. PMID 8164698.

- ^ Koch, The Quest for Consciousness, pp. 216–226

- ^ V. Mark Durand and David H. Barlow (2009). Essentials of Abnormal Psychology. Cengage Learning. pp. 74–75. ISBN 9780495599821. Note: A patient who can additionally describe the current situation may be referred to as "oriented times four".

- ^ a b c Bernat JL (8 Apr 2006). "Chronic disorders of consciousness". Lancet 367 (9517): 1181–1192. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68508-5. PMID 16616561.

- ^ Bernat JL (20 Jul 2010). "The natural history of chronic disorders of consciousness". Neurol 75 (3): 206–207. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e960. PMID 20554939.

- ^ Coleman MR, Davis MH, Rodd JM, Robson T, Ali A, Owen AM, Pickard JD (September 2009). "Towards the routine use of brain imaging to aid the clinical diagnosis of disorders of consciousness". Brain 132 (9): 2541–2552. doi:10.1093/brain/awp183. PMID 19710182.

- ^ Monti MM, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Coleman MR, Boly M, Pickard JD, Tshibanda L, Owen AM, Laureys S (18 Feb 2010). "Willful modulation of brain activity in disorders of consciousness". N Engl J Med 362 (7): 579–589. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0905370. PMID 20130250.

- ^ Seel RT, Sherer M, Whyte J, Katz DI, Giacino JT, Rosenbaum AM, Hammond FM, Kalmar K, Pape TL, et al. (December 2010). "Assessment scales for disorders of consciousness: evidence-based recommendations for clinical practice and research". Arch Phys Med Rehabil 91 (12): 1795–1813. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2011.01.002. PMID 21112421.

- ^ George P. Prigatano and Daniel Schacter (1991). "Introduction". In George Prigatano, Daniel Schacter. Awareness of Deficit After Brain Injury: Clinical and Theoretical Issues. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–16. ISBN 0195059417.

- ^ Kenneth M. Heilman (1991). "Anosognosia: possible neuropsychological mechanisms". In George Prigatano, Daniel Schacter. Awareness of Deficit After Brain Injury: Clinical and Theoretical Issues. Oxford University Press. pp. 53–62. ISBN 0195059417.

- ^ William James (1890). The Principles of Psychology, Volume 1. H. Holt. p. 225.

- ^ Dzogchen Rinpoche (2007). "Taming the mindstream". In Doris Wolter. Losing the Clouds, Gaining the Sky: Buddhism and the Natural Mind. Wisdom Publications. pp. 81–92. ISBN 9780861713592.

- ^ Robert Humphrey (1954). Stream of Consciousness in the Modern Novel. University of California Press. pp. 23–49. ISBN 9780520005853.

- ^ James Joyce (1990). Ulysses. BompaCrazy.com. p. 620.

External links

- Consciousness Studies at the Open Directory Project

- Anthropology of Consciousness

- Consciousness and Cognition

- Consciousness & Emotion

- Journal of Consciousness Studies

- Psyche (ASSC)

Philosophy of mind Philosophers Austin · Bain · Bergson · Bhattacharya · Block · Broad · Dennett · Dharmakirti · Davidson · Descartes · Goldman · Heidegger · Husserl · James · Kierkegaard · Leibniz · Merleau-Ponty · Minsky · Moore · Nagel · Popper · Rorty · Ryle · Searle · Spinoza · Turing · Vasubandhu · Wittgenstein · Zhuangzi · more…Theories Behaviourism · Biological naturalism · Dualism · Eliminative materialism · Emergent materialism · Epiphenomenalism · Functionalism · Identity theory · Interactionism · Materialism · Mind-body problem · Monism · Naïve realism · Neutral monism · Phenomenalism · Phenomenology (Existential phenomenology) · Physicalism · Pragmatism · Property dualism · Representational theory of mind · Solipsism · Substance dualismConcepts Abstract object · Artificial intelligence · Chinese room · Cognition · Concept · Concept and object · Consciousness · Idea · Identity · Ingenuity · Intelligence · Intentionality · Introspection · Intuition · Language of thought · Materialism · Mental event · Mental image · Mental process · Mental property · Mental representation · Mind · Mind-body dichotomy · Pain · Problem of other minds · Propositional attitude · Qualia · Tabula rasa · Understanding · more…Related articles Metaphysics · Philosophy of artificial intelligence · Philosophy of information · Philosophy of perception · Philosophy of selfAppetite · Arousal · Biofeedback · Blushing · Consciousness · Cerebral dominance · Habituation · Lie detection · Orientation · Reaction time · Reflex · Satiation · Self stimulation · Sensation · Sleep · Psychological stressMental processes Cognition Perception Amodal perception · Color perception · Depth perception · Visual perception · Form perception · Haptic perception · Speech perception · Perception as Interpretation · Numeric Value of Perception · Pitch perception · Harmonic perception · Social perceptionMemory Other

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.