- Manchester Town Hall

-

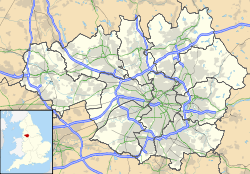

Manchester Town Hall  Shown within Greater Manchester

Shown within Greater ManchesterGeneral information Type Town hall Architectural style Victorian, Gothic Revival Location Manchester

Greater Manchester

EnglandAddress Albert Square

MANCHESTER

M60 2LACoordinates 53°28′45″N 2°14′39″W / 53.4791°N 2.2441°W Current tenants Manchester City Council Construction started 1868 Completed 1877 Renovated 1934, 2011 Cost £775,000 (£54,080,000 as of 2011[1]) Height 87m (clock tower) Design and construction Owner Manchester City Council Architect Alfred Waterhouse Awards and prizes Grade I listed building Manchester Town Hall is a Victorian-era, Neo-gothic municipal building in Manchester, England. The building functions as the ceremonial headquarters of Manchester City Council and houses a number of local government departments.

Completed by architect Alfred Waterhouse in 1877, the building features the imposing Manchester Murals by the artist Ford Madox Brown illustrating the history of the city.

The Town Hall was rated by English Heritage as a Grade I listed building in 1952 and the Town Hall Extension, completed in 1938, was Grade II* listed in 1974. It is regarded as one of the finest interpretations of neogothic architecture in the United Kingdom.[2][3]

Contents

History

Old Town Hall

Manchester's original civic administration was housed in the Police Office in King Street. It was replaced by the first Town Hall, to accommodate the growing local government and its civic assembly rooms. The Town Hall, also located in King Street at the corner of Cross Street, was designed by Francis Goodwin and constructed during 1822–25, much of it by David Bellhouse. The building was designed with a screen of Ionic columns across a recessed centre, in a classicising manner strongly influenced by John Soane. The building was 134 feet long and 76 feet deep, the ground floor housed committee rooms and offices for the Chief Constable, Surveyor, Treasurer, other officers and clerks. The first floor held the Assembly Rooms. The building and land cost £39,587.[4]

As the size and wealth of the city grew, largely as a result of the textile industry, its administration outstripped the existing facilities, and a new building was proposed. The King Street building was subsequently occupied by a lending library and then Lloyds Bank. The facade was removed to Heaton Park in 1912, when the current Lloyds TSB building was erected on the site (No 53 King Street).

New Town Hall

Detail of facades by Alfred Waterhouse

Detail of facades by Alfred Waterhouse

The planning for a new Town Hall began in 1863. The Manchester Corporation demanded in the architecture brief that the new town hall had to be, 'equal if not superior, to any similar building in the country at any cost which may be reasonably required'.[5] The choice of location was influenced by a desire to provide a central, accessible, but relatively quiet site in a respectable district, close to Manchester's banks and municipal offices, next to a large open area, suitable for the display of a fine building.[6] After an investigation of suitable sites, including Piccadilly, the site chosen for the new town hall was an oddly shaped triangle facing onto Albert Square.[7]

A competition was held to design the Town Hall. Of the 137 entries in open competition for the design, Waterhouse's design was chosen, mainly for his ingenious planning,[8] and he was appointed as architect on 1 April 1868.[7] The foundation stone of the new Town Hall was laid on 26 October 1868 by the Lord Mayor of Manchester, Robert Neill. Construction took nine years, used fourteen million bricks,[9] and cost £775,000 (£53.5 million as of 2011).[1][10] The Town Hall was opened by Lord Mayor Abel Heywood, who had championed the project, on 13 September 1877, after Queen Victoria's refusal to attend the opening.[11]

The building exemplifies the Victorian Gothic revival style of architecture, using themes and elements from 13th-century Early English Gothic architecture. The choice was influenced by the wish for a spiritual acknowledgement of Manchester's late medieval heritage in the textile trade of the Hanseatic league and also an affirmation of modernity, the fashionable neo-Gothic style being preferred over the Neoclassical architecture favoured in neighbouring Liverpool. The exterior, faced with hard sandstone quarried near Bradford, Yorkshire, known as "Spinkwell stone",[12] is decorated with sculptures of important figures in Manchester's history. The interior is faced with multi-coloured Architectural terracotta by Gibbs and Canning Limited. The painted ceilings were provided by Best & Lea of Manchester, who had also provided the ceilings in the Natural History Museum, London, also designed by Alfred Waterhouse.

Town Hall Extension

A competition to build a Town Hall Extension was won by Emanuel Vincent Harris in 1927, as well as a separate competition to design Manchester Central Library.[13] Work began on the extension in 1934 and was completed by 1938. The later building features stained-glass windows by George Kruger Gray.[14] N

Charles Herbert Reilly, a well-known architecture critic of the time who was not keen on neogothic architecture, thought the extension was 'dull an drab'[15] while Nikolaus Pevsner believed it was Harris's best work.

Heritage listings

The Town Hall was listed by English Heritage as a Grade I listed building on 25 February 1952,[16] and the extension was Grade II* listed on 3 October 1974.[17]

Features

The rapid growth and accompanying pollution, in Victorian cities caused great problems for architects including denial of light, overcrowding, awkward sites, noise, accessibility and visibility of buildings, and air pollution.

Design stipulations for the Town Hall had Included provision for "the sufficiency of window light supplied throughout the building." This was addressed by the use of a number of architectural devices: suspended first floor rooms, made possible by the use of iron-framed construction, and skylights, extra windows and dormers, "borrowed lights" for interior spaces and glazed white bricks in conjunction with mosaic marble paving in areas where the light was "less strong".[6][18] Clear glass was used in important rooms, with light-coloured tints for coloured glazing, as "the sky of Manchester does not favour the employment of deeply stained glass."[19]

In mid-19th century Manchester, many important Georgian buildings had become blackened by atmospheric pollution. By the 1870s the local soft red Collyhurst sandstone was deemed to be to be unsuitable for public building, and tough Pennine sandstones were preferred.[19] The architectural competition entries for the Town Hall were judged in part on their suitability for the "climate of the district", and sample stone types were investigated.[20] Waterhouse believed that it was a matter of great difficulty to find a stone "proof against the evil influences of the peculiar climate of Manchester" but decided that the Yorkshire-quarried "Spinkwell stone" would resist "the deleterious influences of Manchester atmosphere".[6] The interior decoration was also chosen with a view to providing permanent colour and cleanable surfaces. Public corridors were faced with terracotta rather than plaster, and extensive use was made of stone vaulted ceilings, tiled dados and washable mosaic floors.[21] no Waterhouse's design for Manchester's new Town Hall used a Gothic style with limited carved decoration and a uniform colour. This, along with a limited amount of modelling detail, was a departure from the High Victorian architecture heaviness and use of colour in contemporary Ruskinian Gothic buildings, and the Town Hall was criticised by some Manchester inhabitants for not being Gothic enough.[22] Many also commented on the decision to spend large amounts of money on a building "when most of its architectural effect would be lost because ruined by soot and made nearly invisible by smoke."[22] Waterhouse's design proved successful, however, and although the exterior was blackened by the late 1890s, the stonework was not badly damaged and was in a suitable condition to be to be cleaned and brought back to its original appearance in the late 1960s.

Modern technologies

Despite its medieval styling, the building was designed to support the practical technologies of the 19th century. These included gas lighting, and a warm-air heating system, which provided fresh air drawn through ornamental stone air inlets placed below the windows and admitted behind the hot water pipes and 'coils' of rooms. Warmed, fresh air was also fed into the stairwells and through hollow shafts within the spiral staircases in order to ventilate the corridors.[6] The pipes that supplied the gas for the lighting were ingeniously concealed underneath the banister rails of the spiral staircases.[8]

Exterior and layout

The entrance features twelve exterior statues executed by the firm of Farmer & Brindley, including:

- Gnaeus Julius Agricola, founder of the Roman fort of Mamuciam in year 79

- Henry III of England

- Elizabeth I of England

- Saint George

In the entrance hall are statues of:

Decorating the floor of the entrance hall is a mosaic depicting the bee, the symbol of Manchester being a hive of industry during the 19th century. The bee is carved into many of the pillars and walls about the building.

Clock tower

There is a 280-foot (85 metre) bell tower, housing a carillon of 23 bells: the last 12 of them are hung for full circle change ringing and were manufactured by John Taylor Bellfounders.[23] At 85 metres, it is only 11 metres shorter than St Stephen's Tower which houses Big Ben in London.

The clock bell, Great Abel, is named after Heywood and weighs 8 tons 2.5 cwt. It is inscribed with the initials AH and the Tennyson line Ring out the false, ring in the true.[24] The clock is by Gillett and Bland (predecessor of Gillett and Johnston) and was originally wound using hydraulic power supplied by Manchester Hydraulic Power.[25] Its face bears the inscription Teach us to number our Days, from Psalm 90:12.

Interior

Manchester Murals

Main article: The Manchester MuralsThe hall features an organ by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll and a sequence of twelve murals by Ford Madox Brown. The murals reflect the outstanding themes of Victorian Manchester: Christianity, commerce and the textile industry. They are not true frescos but employ the Gambier Parry process. The murals are:

-

Romans Building a Fort at Mancenion: The building of the fort, to be found now in Manchester's Castlefield, by British slaves under Agricola

-

The Baptism of Edwin: Baptism of Edwin of Northumbria at York, watched by his wife Ethelberga and family

-

The Expulsion of the Danes from Manchester: A colourful depiction of the evacuation of the Danes from the town

-

The Establishment of Flemish Weavers in Manchester A.D. 1363: Queen Philippa of Hainault greets Flemish weavers who were invited to England under Edward III of England's act of 1337.

-

The Trial of Wycliffe A.D. 1377: Perhaps the most impressive of the twelve murals, on which John Wycliffe is depicted on trial, defended by his patron, John of Gaunt. Geoffrey Chaucer, another protegé of Gaunt's, acts as recorder.

-

Crabtree watching the Transit of Venus A.D. 1639: William Crabtree, a draper who lived at Broughton, was asked by a curate friend, Jeremiah Horrocks, to observe the Transit of Venus, on 24 November. Crabtree's diligence and rigour enabled him to correct Horrocks' faulty calculations and to observe the transit on 4 December.

-

Chetham's Life's Dream A.D. 1640: Humphrey Chetham dreams of the school, Chetham's Hospital, to be established by his legacy.

-

Bradshaw's Defence of Manchester A.D. 1642: During the English Civil War, Manchester was laid under siege by Royalists. It was in fact John Rosworm, not Bradshaw, who defended the town.

-

John Kay, Inventor of the Fly Shuttle A.D. 1753: Depicts luddites destroying the shuttle mechanism while Kay is being smuggled to safety.

-

The Opening of the Bridgewater Canal A.D. 1761: The 3rd Earl of Bridgewater owned coal mines in Worsley , and collaborated with engineer James Brindley to build a canal to carry coal into the heart of Manchester.

-

Dalton collecting Marsh-Fire Gas: The seminal studies that led John Dalton to his atomic theory

See also

- Grade I listed buildings in Greater Manchester

- Grade II* listed buildings in Greater Manchester

- Rochdale Town Hall

Film set

Due to its resemblance to the Palace of Westminster, Manchester Town Hall has served as a filming location for both television shows and films with scenes set in the House of Commons and the House of Lords. In the case of the BBC series State of Play, the location was partnered with a set of the House of Commons chamber at nearby Granada Studios.[26]>[27]

References

- Notes

- ^ a b UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Lawrence H. Officer (2010) "What Were the UK Earnings and Prices Then?" MeasuringWorth.

- ^ "Manchester town hall: 'A building that understands its place in history' – video". The Guardian. 9 September 2011. http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/video/2011/sep/09/manchester-town-hall-video. Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- ^ Hartwell, Clare (2002). Pevsner - Manchester. Penguin Books. p. 84.

- ^ Parkinson-Bailey 2000, p. 60

- ^ Hartwell. p. 71.

- ^ a b c d Bowler 2000, p. 175.

- ^ a b Hartwell 2001, p. 71

- ^ a b Anon, "History of Manchester Town Hall", Manchester City Council web pages (Manchester City council), http://www.manchester.gov.uk/info/200064/local_history_and_heritage/1986/a_history_of_manchester_town_hall/1, retrieved 6 February 2010

- ^ Edensor, Tim; Drew, Ian, Building Stone in the City of Manchester, http://www.sci-eng.mmu.ac.uk/manchester_stone/images.asp?page1=3&vartype=building, retrieved 4 February 2010

- ^ Anon. "Municipal Buildings: Details of facades, Town Hall, Manchester". RIBA How we built Britain. RIBA. http://www.architecture.com/HowWeBuiltBritain/HistoricalPeriods/Victorian/MunicipalBuildings/ManchesterTownHallFacades.aspx. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ^ Wyke, Terry; Cocks, Harry (2004), Public sculpture of Greater Manchester, Liverpool University Press, pp. 24, ISBN 978-0-85323-567-5

- ^ Edensor, Tim; Drew, Ian. "Spinkwell stone". http://www.sci-eng.mmu.ac.uk/manchester_stone/images.asp?page1=3&vartype=quarry&offset=0. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ^ Stamp, Gavin (2004), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/60777, retrieved 4 February 2010

- ^ Hartwell 2001, pp. 85–86

- ^ Hartwell. p. 85.

- ^ Town Hall, Heritage Gateway, http://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=387871&resourceID=5, retrieved 26 December 2009

- ^ Town Hall Extension, Heritage Gateway, http://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=388286&resourceID=5, retrieved 4 February 2010

- ^ Bowler 2000, pp. 177–9

- ^ a b Bowler 2000, p. 180

- ^ Bowler 2000, p. 181.

- ^ Bowler 2000, p. 184

- ^ a b Bowler 2000, p. 183.

- ^ Bells, http://dove.cccbr.org.uk/detail.php?searchString=Manchester%2C+Town+Hall&Submit=++Go++&DoveID=MANCHSTR+T, retrieved 2010-02-05

- ^ Dove, R. H. (1982) A Bellringer's Guide to the Church Bells of Britain and Ringing Peals of the World, 6th ed. Guildford: Viggers; p. 71

- ^ Anon. "Hydraulic Pumping Engine". Museum of Science and Industry. MOSI. http://emu.msim.org.uk/htmlmn/collections/online/browsethemes/relatedobjects_lower.php?irn=2611&start=1. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ Bourne, Dianne (13 February 2011). Manchester Evening News. http://menmedia.co.uk/manchestereveningnews/tv_and_showbiz/s/1408028_hollywood_stars_out_on_the_town_while_working_on_new_margaret_thatcher_film_the_iron_lady. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ Abbott, Paul. Audio commentary on the DVD release of State of Play. BBC Worldwide. BBCDVD 1493.

- Bibliography

- Bowler, Catherine; Brinblecombe, Peter (2000), "Environmental Pressures on Building Design and Manchester's John Rylands Library", Journal of Design and History (The Design History Society) 13 (3): 175–191, http://jdh.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/13/3/175

- Hartwell, Clare (2001), Manchester, Pevsner Architectural Guides, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-071131-8

- Parkinson-Bailey, John J. (2000), Manchester: An Architectural History, Manchester: Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-5606-3

External links

Categories:- City and town halls in England

- Grade I listed buildings in Manchester

- Grade I listed government buildings

- Visitor attractions in Manchester

- Alfred Waterhouse buildings

- Gothic Revival architecture in Greater Manchester

- Terracotta

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.