- Mesoamerican rubber balls

-

A solid rubber ball used (or similar to those used) in the Mesoamerican ballgame, 300 BC to 250 AD, Kaminaljuyu. The ball is 3 inches (almost 8 cm) in diameter, a size that suggests it was used to play a hand-ball game. Behind the ball is a manopla, or handstone, which was used to strike the ball, 900 BC to 250 AD, also from Kaminaljuyu.

A solid rubber ball used (or similar to those used) in the Mesoamerican ballgame, 300 BC to 250 AD, Kaminaljuyu. The ball is 3 inches (almost 8 cm) in diameter, a size that suggests it was used to play a hand-ball game. Behind the ball is a manopla, or handstone, which was used to strike the ball, 900 BC to 250 AD, also from Kaminaljuyu.

Ancient Mesoamericans were the first people to invent rubber balls, sometime before 1600 BCE, and used them in a variety of roles. The Mesoamerican ballgame, for example, employed various sizes of solid rubber balls and balls were burned as offerings in temples, buried in votive deposits, and laid in sacred bogs and cenotes.

Contents

Rubber in Mesoamerica

Ancient rubber was made from latex of the rubber tree (Castilla elastica), which is indigenous to the tropical areas of southern Mexico and Central America. The latex was made into rubber by mixing it with the juice of what was likely Ipomoea alba (a species of morning glory), a process which preceded Goodyear's vulcanization by several millennia. [1] The resultant rubber would then be formed into rubber strips, which would be wound around a solid rubber core to build the ball.[2]

Archaeological evidence indicates that rubber was already in use in Mesoamerica by the Early Formative Period – a dozen balls were found in the Olmec El Manati sacrificial bog and dated to roughly 1600 BCE.[3] By the time of the Spanish Conquest, 3000 years later, rubber was being exported from the tropical zones to sites all over Mesoamerica.

Iconography suggests that although there were many uses for rubber, rubber balls both for offerings and for ritual ballgames were the primary products. To both the Aztecs and the Maya, the rubber latex that flowed from the tree represented blood and semen.[4] Rubber was therefore symbolic of fertility, and was often burned, buried, or (fortunately for archaeology) laid in a sacrificial pool as an offering to various deities.

Size and weight

The exact sizes or weights of the balls actually used in the ballgame are not known. Sizes varied not only according to the ballgame version played (i.e. hip-ball, hand-ball, stick-ball, etc.), but even within a given version. For example, Late Classic hip-ball stone scoring rings had holes of differing sizes, strongly implying that the balls were not of uniform size either.[5]

Most of the ancient balls that have been retrieved were originally laid down as offerings, and there is no evidence that any of these were used in the ballgame. In fact, some of these extant votive balls were created specifically as offerings. However, ancient iconography as well as modern game balls can provide insight. For example, archaeologist Laura Filloy Nadal compiled the following comparison of modern ball sizes:[6]

Ballgame Version Ball struck with Ball diameter Ball weight Ulama de cadera Hip ≤20 cm (8 in) 3–4 kg (6½-9 lbs) Ulama de mazo[7] Heavy bat, 5–7 kg Unavailable 500-600 gr (18-21 oz) Ulama de brazo Forearm ≈11 cm (4½ in) ≤500 gr (16-18 oz) Pelota mixteca Heavy glove 8-10 cm (3-4 in) 170-280 gr (6-9 oz) It is therefore assumed by most researchers that the ancient hip-ball was roughly the size of a volleyball and weighed between 3 and 4 kg (6½-9 lbs) or 15 times heavier than the air-filled volleyball. The ancient hand-ball or stick-ball was probably slightly larger and heavier than a modern-day baseball.

Only roughly 100 pre-Columbian rubber artifacts have been recovered, all of which were found in still, freshwater contexts,[8] sites that include El Manati, the Sacred Cenote at Chichen Itza, and the ruins of Tenochtitlan.The following table summarizes data on some of the ancient balls recovered:[9]

Location Culture # found Ball diameter Period El Manati Olmec 5[10] 10-14 cm 1600–1700 BCE El Manati Olmec 2 22 cm 1200 BCE Sacred Cenote Maya Unknown 4 cm 850 - 1550 CE[1] Main ballcourt, Tenochtitlan Aztec 2 7 cm[11] Early 16th century? House of Eagles, Tenochtitlan Aztec 4[12] 6-8½ cm Early 16th century? Oversized balls, skull-balls, and captive-balls

Although there is no artifact evidence uncovered to support such speculation, depictions of overly large balls or balls which appear to contain skulls and even captives have created much conjecture.

A Maya limestone staircase riser, ca. 700 - 900 CE. Against the backdrop of a staircase, two nobles play the ballgame with an overly large, perhaps symbolic, ball. The ball itself contains two glyphs, a "14" and an unknown glyph that has been speculatively translated as "handspan". Height: 25.1 cm; length: 43.2 cm.

A Maya limestone staircase riser, ca. 700 - 900 CE. Against the backdrop of a staircase, two nobles play the ballgame with an overly large, perhaps symbolic, ball. The ball itself contains two glyphs, a "14" and an unknown glyph that has been speculatively translated as "handspan". Height: 25.1 cm; length: 43.2 cm.

Many depictions of ballplayers show balls of huge size, perhaps up to 1 metre (1.1 yd) or more in diameter. These depictions include not only the image on the right, but the "Dallas vase", the Chinkultic court marker, and a Western Mexico ceramic ballcourt.[13] Most researchers believe that these depictions are exaggerations,[14] in large part because a solid ball one meter in diameter would be nearly too heavy to move, weighing close to 500 kg (over 1000 lbs). Researcher Marvin Cohodas has suggested that these depictions are either symbolic, or that the outsized ball and outlandish costumes might portray "a few heavily costumed nobles [taking] perfunctory shots at an oversize ball . . . perhaps re-enacting a cosmogonic myth".[15]

Nonetheless, Marc Zender of the Peabody Museum has interpreted a common ball-glyph (seen for example on the ball at right) as "handspan", a circumference measurement of roughly 8½ inches (22 cm). Combined with coefficients of 9, 10, 12, 13, and 14, Zender contends that "Classic Maya ballgame balls would have measured from just over two feet to well over three feet in diameter (62 to 96 cm)".[16]

The images of skulls superimposed on balls found at the Great Ballcourt at Chichen Itza and on several Maya artifacts, have led several researchers to suggest that skulls of the sacrificial victims were wrapped with rubber to create hollow balls.[17] Other than these images, however, there is no evidence to support such an assertion.[18]

On Altar 8 at Tikal as well as on the Hieroglyphic Stairs at Yaxchilan, captives appear to be inside, or are at least superimposed upon, balls. Like those of oversized and skull-balls, most researchers doubt that such images are to be taken literally. Schele and Miller, for example, state that the captive is "bound and trussed in the form of a ball".[19]

Notes

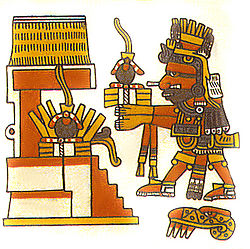

In this detail from the late 15th century Codex Borgia, the Aztec god Xiuhtecuhtli brings a rubber ball offering to a temple. The rubber balls each hold a quetzal feather, part of the offering.

In this detail from the late 15th century Codex Borgia, the Aztec god Xiuhtecuhtli brings a rubber ball offering to a temple. The rubber balls each hold a quetzal feather, part of the offering.

- ^ a b Hosler, et al.

- ^ Filloy Nadal discusses the Aztecs' use of "ancient rolling technique" (page 30) while Ortiz discusses the use of this technique by the Olmecs (page 244).

- ^ Ortíz C.

- ^ Filloy Nadal, p.30.

- ^ Whittington, p. 242.

- ^ Filloy Nadal, page 30.

- ^ Information on the ulama de mazo ball weight comes from Leyenaar (2001) pp. 125-126.

- ^ Filloy Nadal, p.26, although Hosler et al. refer to "a few hundred" artifacts. Of these artifacts, only a few dozen are rubber balls.

- ^ See Ortiz for El Manati data, and Filloy Nadal for Maya and Aztec data, except where noted otherwise.

- ^ Another 5 balls were found by villagers, but without archaeological context.

- ^ According to Filloy Nadal, p. 28, these were miniature "votive representations".

- ^ These balls were grooved and intended as offerings (Filloy Nadal, p. 28).

- ^ The first three examples are from the Maya culture. The western Mexico ceramic is from Nayarit -- 300 BCE to 100 CE -- and can be found at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (see Whittington, p. 163).

- ^ For example, Coe et al., p. 109.

- ^ Cohodas, p. 259.

- ^ Zender, p.4.

- ^ See the Sport of Life and Death website.

- ^ Miller (2001), p. 81, finds that the Chichen Itza panels "suggest" the use of skull-balls. Schele and Miller say "That a skull might serve as a ball with a hollow core is suggested only by depictions of balls with skulls inside" (p. 248 as well as p. 253).

- ^ Schele and Miller, p. 249.

References

-

- Coe, Michael D.; Dean Snow, and Elizabeth P. Benson (1986). Atlas of Ancient America. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0816011990.

- Filloy Nadal, Laura (2001). "Rubber and Rubber Balls in Mesoamerica". In E. Michael Whittington (ed.). The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame. New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 20–31. ISBN 0-500-05108-9. OCLC 49029226.

- Hosler, Dorothy; Sandra Burkett, and Michael Tarkanian (1999, June 18). "Prehistoric Polymers: Rubber Processing in Ancient Mesoamerica". Science (Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science) 284 (5422): 1988–1991. doi:10.1126/science.284.5422.1988. ISSN 0036-8075. OCLC 207960606. PMID 10373117.

- Leyenaar, Ted (2001). ""The Modern Ballgames of Sinaloa: a Survival of the Aztec Ullamaliztli"". In E. Michael Whittington (ed.). The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame. New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 122–129. ISBN 0-500-05108-9. OCLC 49029226.

- Miller, Mary Ellen (2001). "The Maya Ballgame: Rebirth in the Court of Life and Death". In E. Michael Whittington (ed.). The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame. New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 20–31. ISBN 0-500-05108-9. OCLC 49029226.

- Ortíz C., Ponciano; and María del Carmen Rodríguez (1999). "Olmec Ritual Behavior at El Manatí: A Sacred Space". In David C. Grove and Rosemary A. Joyce (eds.) (PDF). Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica (Dumbarton Oaks etexts ed.). Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. pp. 225–254. ISBN 0-88402-252-8. http://www.doaks.org/Social/social09.pdf. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- Ortíz C., Ponciano; María del Carmen Rodríguez and Alfredo Delgado (1992). "Las ofrendas de El Manatí y su posible asociación con el juego de pelota: un yugo a destiempo". In María Teresa Uriarte (ed.). El juego de pelota en Mesoamérica: raíces y supervivencia. México D.F.: Siglo XXI Editores and Casa de Cultura, Gobierno del Estado de Sinaloa. pp. 55–67. ISBN 968-23-1837-8. OCLC 28891266. (Spanish)

- Schele, Linda; and Mary Ellen Miller (1992) [1986]. Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. Justin Kerr (photographer) (2nd paperback, reprint with corrections ed.). New York: George Braziller. ISBN 0-8076-1278-2. OCLC 41441466.

- Zender, Marc (2004). "Glyphs for “Handspan” and “Strike” in Classic Maya Ballgame Texts". The PARI Journal 4 (4). ISSN 0003-8113. http://www.mesoweb.com/pari/publications/journal/404/Handspan.pdf.

Categories:- Mesoamerican society

- Ball games

- Ancient sports

- Native American sports and games

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.