- Comoving distance

-

Physical cosmology

Universe · Big Bang

Age of the universe

Timeline of the Big Bang

Ultimate fate of the universeEarly universeExpanding universeComponentsIn standard cosmology, comoving distance and proper distance are two closely related distance measures used by cosmologists to define distances between objects. Proper distance roughly corresponds to where a distant object would be at a specific moment of cosmological time, measured using a long series of rulers stretched out from our position to the object's position at that time, and which can change over time due to the expansion of the universe. Comoving distance factors out the expansion of the universe, giving a distance that does not change in time due to the expansion of space. Comoving distance and proper distance are defined to be equal at the present time.[clarification needed]

Contents

Comoving coordinates

While general relativity allows one to formulate the laws of physics using arbitrary coordinates, some coordinate choices are more natural (e.g. they are easier to work with). Comoving coordinates are an example of such a natural coordinate choice. They assign constant spatial coordinate values to observers who perceive the universe as isotropic. Such observers are called "comoving" observers because they move along with the Hubble flow.

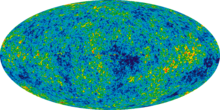

A comoving observer is the only observer that will perceive the universe, including the cosmic microwave background radiation, to be isotropic. Non-comoving observers will see regions of the sky systematically blue-shifted or red-shifted. Thus isotropy, particularly isotropy of the cosmic microwave background radiation, defines a special local frame of reference called the comoving frame. The velocity of an observer relative to the local comoving frame is called the peculiar velocity of the observer.

Most large lumps of matter, such as galaxies, are nearly comoving, i.e., their peculiar velocities (due to gravitational attraction) are low.

The comoving time coordinate is the elapsed time since the Big Bang according to a clock of a comoving observer and is a measure of cosmological time. The comoving spatial coordinates tell us where an event occurs while cosmological time tells us when an event occurs. Together, they form a complete coordinate system, giving us both the location and time of an event.

Space in comoving coordinates is usually referred to as being "static", as most bodies on the scale of galaxies or larger are approximately comoving, and comoving bodies have static, unchanging comoving coordinates. So for a given pair of comoving galaxies, while the proper distance between them would have been smaller in the past and will become larger in the future due to the expansion of space, the comoving distance between them remains constant at all times.

The expanding Universe has an increasing scale factor which explains how constant comoving distances are reconciled with proper distances that increase with time.

- See also: metric expansion of space.

Comoving distance and proper distance

Comoving distance is the distance between two points measured along a path defined at the present cosmological time. For objects moving with the Hubble flow, it is deemed to remain constant in time. The comoving distance from an observer to a distant object (e.g. galaxy) can be computed by the following formula:

where a(t′) is the scale factor, te is the time of emission of the photons detected by the observer, t is the present time, and c is the speed of light in vacuum.

Despite being an integral over time, this does give the distance that would be measured by a hypothetical tape measure at fixed time t, i.e. the "proper distance" as defined below, divided by the scale factor a(t) at that time. For a derivation see (Davis and Lineweaver, 2003) "standard relativistic definitions".

- Definitions

- Many textbooks use the symbol

for the comoving distance. However, this

for the comoving distance. However, this  must be distinguished from the coordinate distance r in the commonly-used comoving coordinate system for a FLRW universe where the metric takes the form

must be distinguished from the coordinate distance r in the commonly-used comoving coordinate system for a FLRW universe where the metric takes the form

.

.- In this case the comoving coordinate distance

is related to

is related to  by

by  if k=0 (a spatially flat universe), by

if k=0 (a spatially flat universe), by  if k=1 (a positively-curved 'spherical' universe), and by

if k=1 (a positively-curved 'spherical' universe), and by  if k=-1 (a negatively-curved 'hyperbolic' universe).[1]

if k=-1 (a negatively-curved 'hyperbolic' universe).[1]

- Most textbooks and research papers define the comoving distance between comoving observers to be a fixed unchanging quantity independent of time, while calling the dynamic, changing distance between them proper distance. On this usage, comoving and proper distances are numerically equal at the current age of the universe, but will differ in the past and in the future; if the comoving distance to a galaxy is denoted

, the proper distance

, the proper distance  at an arbitrary time

at an arbitrary time  is simply given by

is simply given by  where

where  is the scale factor. (e.g. Davis and Lineweaver, 2003) The proper distance

is the scale factor. (e.g. Davis and Lineweaver, 2003) The proper distance  between two galaxies at time t is just the distance that would be measured by rulers between them at that time.[2]

between two galaxies at time t is just the distance that would be measured by rulers between them at that time.[2]

Uses of the proper distance

Cosmological time is identical to locally measured time for an observer at a fixed comoving spatial position, that is, in the local comoving frame. Proper distance is also equal to the locally measured distance in the comoving frame for nearby objects. To measure the proper distance between two distant objects, one imagines that one has many comoving observers in a straight line between the two objects, so that all of the observers are close to each other, and form a chain between the two distant objects. All of these observers must have the same cosmological time. Each observer measures their distance to the nearest observer in the chain, and the length of the chain, the sum of distances between nearby observers, is the total proper distance.[3]

It is important to the definition of both comoving distance and proper distance in the cosmological sense (as opposed to proper length in special relativity) that all observers have the same cosmological age. For instance, if one measured the distance along a straight line or spacelike geodesic between the two points, observers situated between the two points would have different cosmological ages when the geodesic path crossed their own world lines, so in calculating the distance along this geodesic one would not be correctly measuring comoving distance or cosmological proper distance. Comoving and proper distances are not the same concept of distance as the concept of distance in special relativity. This can be seen by considering the hypothetical case of a universe empty of mass, where both sorts of distance can be measured. When the density of mass in the FLRW metric is set to zero (an empty 'Milne universe'), then the cosmological coordinate system used to write this metric becomes a non-inertial coordinate system in the flat Minkowski spacetime of special relativity, one where surfaces of constant time-coordinate appear as hyperbolas when drawn in a Minkowski diagram from the perspective of an inertial frame of reference.[4] In this case, for two events which are simultaneous according the cosmological time coordinate, the value of the cosmological proper distance is not equal to the value of the proper length between these same events,(Wright) which would just be the distance along a straight line between the events in a Minkowski diagram (and a straight line is a geodesic in flat Minkowski spacetime), or the coordinate distance between the events in the inertial frame where they are simultaneous.

If one divides a change in proper distance by the interval of cosmological time where the change was measured (or takes the derivative of proper distance with respect to cosmological time) and calls this a "velocity", then the resulting "velocities" of galaxies or quasars can be above the speed of light, c. This apparent superluminal expansion is not in conflict with special or general relativity, and is a consequence of the particular definitions used in cosmology. Even light itself does not have a "velocity" of c in this sense; the total velocity of any object can be expressed as the sum

where

where  is the recession velocity due to the expansion of the universe (the velocity given by Hubble's law) and

is the recession velocity due to the expansion of the universe (the velocity given by Hubble's law) and  is the "peculiar velocity" measured by local observers (with

is the "peculiar velocity" measured by local observers (with  and

and  , the dots indicating a first derivative), so for light

, the dots indicating a first derivative), so for light  is equal to c (-c if the light is emitted towards our position at the origin and +c if emitted away from us) but the total velocity

is equal to c (-c if the light is emitted towards our position at the origin and +c if emitted away from us) but the total velocity  is generally different than c.(Davis and Lineweaver 2003, p. 19) Even in special relativity the coordinate speed of light is only guaranteed to be c in an inertial frame, in a non-inertial frame the coordinate speed may be different than c;[5] in general relativity no coordinate system on a large region of curved spacetime is "inertial", but in the local neighborhood of any point in curved spacetime we can define a "local inertial frame" and the local speed of light will be c in this frame,[6] with massive objects such as stars and galaxies always having a local speed smaller than c. The cosmological definitions used to define the velocities of distant objects are coordinate-dependent - there is no general coordinate-independent definition of velocity between distant objects in general relativity (Baez and Bunn, 2006). The issue of how best to describe and popularize the apparent superluminal expansion of the universe has caused a minor amount of controversy. One viewpoint is presented in (Davis and Lineweaver, 2003).

is generally different than c.(Davis and Lineweaver 2003, p. 19) Even in special relativity the coordinate speed of light is only guaranteed to be c in an inertial frame, in a non-inertial frame the coordinate speed may be different than c;[5] in general relativity no coordinate system on a large region of curved spacetime is "inertial", but in the local neighborhood of any point in curved spacetime we can define a "local inertial frame" and the local speed of light will be c in this frame,[6] with massive objects such as stars and galaxies always having a local speed smaller than c. The cosmological definitions used to define the velocities of distant objects are coordinate-dependent - there is no general coordinate-independent definition of velocity between distant objects in general relativity (Baez and Bunn, 2006). The issue of how best to describe and popularize the apparent superluminal expansion of the universe has caused a minor amount of controversy. One viewpoint is presented in (Davis and Lineweaver, 2003).Proper distance vs. comoving distance from small galaxies to galaxy clusters

Within small distances and short trips, the expansion of the universe during the trip can be ignored. This is because the travel time between any two points for a non-relativistic moving particle will just be the proper distance (i.e. the comoving distance measured using the scale factor of the universe at the time of the trip rather than the scale factor "now") between those points divided by the velocity of the particle. If the particle is moving at a relativistic velocity, the usual relativistic corrections for time dilation must be made.

See also

- Distance measures (cosmology) for comparison with other distance measures

- Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric for information about the most popular cosmological model

- Shape of the universe

References

- ^ See pages 9-12 of The Cosmological Background Radiation by Marc Lachièze-Rey and Edgard Gunzig, or p. 263 Measuring the Universe: The Cosmological Distance Ladder by Stephen Webb.

- ^ see p. 4 of Distance Measures in Cosmology by David W. Hogg.

- ^ Steven Weinberg, Gravitation and Cosmology (1972), p. 415

- ^ See the diagram on p. 28 of Physical Foundations of Cosmology by V. F. Mukhanov, along with the accompanying discussion.

- ^ see p. 219 of Relativity and the Nature of Spacetime by Vesselin Petkov

- ^ see p. 94 of An Introduction to the Science of Cosmology by Derek J. Raine, Edwin George Thomas, and E. G. Thomas

External links

- Distance measures in cosmology

- Ned Wright's cosmology tutorial

- iCosmos: Cosmology Calculator (With Graph Generation )

- Weinberg, Steven (1972)

- Peebles (1993)

- Davis and Lineweaver, Expanding Confusion

- Ned Wright's Javascript cosmology calculator

- General method, including locally inhomogeneous case and Fortran 77 software

- cosmdist-0.2.0 - command line and/or C or Fortran library, based on GNU Scientific Library, for dp,dpm,t as functions of z and their inverses

Categories:- Physical cosmology

- Coordinate charts in general relativity

- Physical quantities

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.