- Priestly Blessing

-

Priestly Blessing Large crowds congregate on Passover at the Western Wall to receive the priestly blessing

Halakhic texts relating to this article: Torah: Numbers 6:23–27 Shulchan Aruch: Orach Chayim 128–130 * Not meant as a definitive ruling. Some observances may be rabbinical, customs or Torah based. The Priestly Blessing, (Hebrew: ברכת כהנים; translit. Birkat Kohanim), also known in Hebrew as Nesiat Kapayim, (lit. Raising of the Hands), or Dukhanen (from the Yiddish word dukhan - platform - because the blessing is given from a raised rostrum)[1], is a Jewish prayer recited by Kohanim during certain Jewish services. It is based on a scriptural verse: "They shall place My name upon the children of Israel, and I Myself shall bless them."[2] It consists of the following Biblical verses (Numbers 6:24–26):

- May the LORD (YHWH) bless you and guard you -

- יְבָרֶכְךָ יְהוָה, וְיִשְׁמְרֶךָ

- ("Yivorekhekhaw Adonai v'yishm'rekhaw ...)

- May the LORD make His face shed light upon you and be gracious unto you -

- יָאֵר יְהוָה פָּנָיו אֵלֶיךָ, וִיחֻנֶּךָּ

- ("Yo'ayr Adonai pawnawv aylekhaw vikhoonekhaw ...)

- May the LORD lift up His face unto you and give you peace -

- יִשָּׂא יְהוָה פָּנָיו אֵלֶיךָ, וְיָשֵׂם לְךָ שָׁלוֹם

- ("Yisaw Adonai pawnav aylekhaw v'yasaym l'khaw shalom.")

Contents

Biblical source

The source of the text is Numbers 6:23–27, where Aaron and his sons bless the Israelites with this blessing.

This is the oldest known Biblical text that has been found; amulets with these verses written on them have been found in graves in dating from the First Temple Period, and are now in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

Various interpretations of these verses connect them to the three Patriarchs; Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, or to three attributes of God: Mercy, Courage, and Glory.

In Jewish law and custom

- Only Kohanim (i.e., adult - age 13 or older - males in direct patrilineal descent from Aaron) can perform the Priestly Blessing. And the blessing should be performed only in the presence of a minyan (quorum of ten adult males) - even if the Kohanim themselves must be included for a total of ten.[3]

- The Torah prohibits a Kohen from reciting the blessing while under the influence of alcohol[4], or in the period immediately following the death of a close relative [5].

- All Kohanim present are obligated to participate, unless disqualified in some way.[6] If a Kohen does not wish to participate, he must leave the sanctuary for the duration of the blessing. A Kohen may be disqualified by, e.g., having imbibed too much alcohol, having a severe speech impediment, blindness, having taken a human life, having married a disqualifying wife (such as a divorcee), the recent death of a close relation.[7]

- A Kohen who is on bad terms with the congregation or who is unwilling to perform the ritual should not perform it.[8]

- It is customary that, once the Kohanim are assembled on the platform, the canter or prayer leader will prompt them by reciting each word of the blessing and the Kohanim will then repeat that word. This custom is especially followed if only one kohen is available to give the blessing. Apparently this prompting is done to avoid errors or embarrassment if any of the kohanim should be ignorant of the words of the recitation. However, if there are a number of kohanim, they may say the first word of the blessing ("Yevorekhekhaw") without the prompting, presumably to demonstrate their familiarity with the ritual.[9]

- The Mishnah records advise that a person who is troubled by a dream should reflect on it when the Kohanim recite their blessing. This practice is still done in many Orthodox communities.[10] It is also recited at bedtime.[11] Both uses derive from the Song of Songs 3:7-8, telling of 60 armed guards surrounding Solomon's bedchamber to protect him from "night terrors"; the 60 letters in the [Hebrew] text of the blessing similarly defend against night terrors.

- In many traditional Jewish communities it is the custom for congregants to spread their tallitot over their own heads during the blessing and not look at the Kohanim. If a man has children, they will come under his tallit to be blessed, even if they are quite old.

- This blessing is also used by some parents to bless their children on Friday night before the beginning of the Shabbat meal. Some rabbis will say the blessing to a boy at his bar mitzvah or to a girl at her bat mitzvah. It is usually prefaced, for boys with a request for God to make the child like Ephraim and Manasseh These were the two sons of Joseph) who are remembered because according to tradition, they never fought with one another. For girls the traditional request is God to make them like Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah, the Matriarchs of the Jewish people.

- It also may be said before a long journey, and some people will write it out and wear/keep it as an amulet. It is often used in the liturgy as the first section of Torah to be read in the morning after reciting the blessing before studying Torah.

- In the case where no Kohanim are present in the synagogue (but there still is a minyan) the hazzan will read the prayer verse by verse, and the congregation will respond after each verse with "ken yehi ratzon" (May it be God's Will). This response is used instead of "Amen", because the hazzan is merely "mentioning" the blessing, essentially quoting it rather than actually performing the ritual.[12] However, some congregations (including Chabad) do indeed respond "Amen". This response is also employed on days and times when the Amidah is repeated but the Kohanim do not recite the priestly blessing.[13] However, according to Abudirham, since the Priestly Blessing is not a conventional benediction (that would begin with "Blessed are Thou ..."), but rather a prayer for peace, ken yehi ratzon is the more appropriate response at all times.[14]

When performed

This ceremony is traditionally performed daily in Israel (except in Galilee)[15], and among most Sephardi Jews worldwide, every day during the repetition of the Shacharit Amidah. On Sabbath and festivals it is also recited during the repetition of the Musaf prayer. On Yom Kippur the ceremony is performed during the Ne'ila service as well. On other fast days it is performed at Mincha, if said in the late afternoon. The reason for offering the blessing in the afternoon only on Fast days is that the Kohanim are forbidden to eat and (especially) to drink alcohol prior to the ceremony.[16]

In the Diaspora in Ashkenazic Orthodox communities, the ceremony is performed only on Pesach, Shavuot, Sukkot, Shemini Atzeret, Rosh Hashanah, and Yom Kippur.[17] German communities perform it at both Shaharit and Musaf, while on Yom Kippur it is performed at Neilah as well. Eastern European congregations only perform it at Musaf. On Simchat Torah, some communities recite it during Musaf, and others during Shacharit, to enable Kohanim to participate in the custom drinking alcohol during the Torah reading between Shacharit and Musaf. On weekdays and Shabbat, in Ashkenazic diaspora communities, the blessing is not recited by Kohanim. Instead, it is recited only by the shaliach tzibbur (prayer leader), or a hazzan (cantor), after the Modim prayer, towards the end of the Amidah, without any special chant or gestures.[18] This Ashkenazic practice is based on a Rabbinic ruling of the Remoh, who argued that the Kohanim were commanded to bless the people with joy (besimcha) and that Kohanim in the diaspora could not be expected to feel joyful except on the above-mentioned holidays where all Jews are commanded to feel joy.[19]

Procedure

At the beginning of the ceremony, those descended from the tribe of Levi, the Leviim in the congregation wash the hands of the Kohanim and then the Kohanim remove their shoes (if they are unable to remove their shoes without using their hands, the shoes are removed prior to the washing), and walk up to the platform in front of the ark, at the front of the synagogue. The use of a platform is implied in Leviticus 9:22. They cover their heads with their tallitot, recite the blessing over the performance of the mitzvah, turn to face the congregation, and then the hazzan or prayer leader slowly and melodiously recites the three verse blessing, with the Kohanim repeating it word by word after him. After each verse, the congregation responds Amen.

- Raising the hands

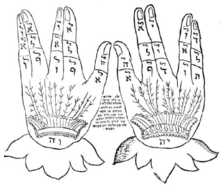

Position of the Kohen's fingers and hands when blessing the congregation.

Position of the Kohen's fingers and hands when blessing the congregation.

During the course of the blessing, the hands of the Kohanim are spread out over the congregation, with the fingers of both hands separated so as to make five spaces between them; the spaces are (1) between the ring finger and middle finger of each hand, (2) between the index finger and thumb of each hand, and (3) the two thumbs touch each other at the knuckle and the aperture is the space above or below the touching knuckles[20]. Each kohen's tallit is draped over his head and hands so that the congregation cannot see his hands while the blessing is said. Performing the ceremony of the priestly blessing is known in Yiddish as duchening, a reference to the "duchan" (Heb: platform) on which the blessing is said. The tradition of covering the hands stems from the biblical prohibition against a Kohen with hands that are disfigured in any way from offering the blessing. The rabbis softened this prohibition by saying that a Kohen with disfigured hands to which the community had become accustomed could bless. In later centuries, the practice became for all Kohanim to cover their hands so that any disfigurement would not be seen by the Congregation. Unfortunately, this gave rise to folklore that one should not see the hands of the Kohen or even that harm would befall someone who sees the hands of the Kohen. Even more unfortunately, this superstition gave rise to an extreme practice in which some congregants will turn their backs to the Kohanim so as to avoid any possibility of seeing their hands -- a practice unsupported by any rabbinic source that displays the ultimate disrespect for a divine blessing.

The Talmud describes God as peering through the "lattice" formed by the hands of the Kohanim, referencing the verse in the Song of Songs (2:9):

-

- My beloved is like a gazelle or a young hart

- Behold, he stands behind our wall

- He looks in through the windows

- Peering through the lattices (הַחֲרַכִּים).

Ha-kharakim means "the lattices" and this is the only place it occurs in the Bible, but splitting off and treating the definite article as a numeral produces ה׳ חֲרַכִּים -- "[peering through] five lattices".[21]

- Prayer chant

In some communities it is customary for the Kohanim to raise their hands and recite an extended musical chant without words before reciting the last word of each phrase. There are different tunes for this chant in different communities. Aside from its pleasant sound, the chant is done so that the congregation may silently offer certain prayers containing individual requests of G-d after each of the three blessings of the Kohanim. Because supplications of this nature are not permitted on Shabbat, the chant is also not done on Shabbat. In Israel, this chanting is not the custom.

Variation among Jewish denominations

Conservative Judaism

In Conservative Judaism, the majority of congregations do not perform the priestly blessing ceremony, but some do. In some American Conservative congregations that perform the ceremony, a bat kohen (daughter of a priest) can perform it as well.[22] Conservative Judaism has also lifted some of the restrictions on Kohanim including prohibited marriages. The Masorti movement in Israel, and some Conservative congregations in North America, require male kohanim as well, and retain restrictions on Kohanim.

- Reform, Reconstructionist and Liberal Judaism

In Liberal (and American Reform) congregations, the concept of the priesthood has been largely abandoned, along with other caste and gender distinctions. Thus, this blessing is usually omitted or simply read by the hazzan. North American Reform Jews omit the Musaf service, as do most other liberal communities, and so if they choose to include the priestly blessing, it is usually appended to the end of the Shacharit Amidah. Some congregations, especially Reconstructionist ones, have the custom of the congregation spreading their tallitot over each other and blessing each other that way.

This custom was started when a Reconstructionist rabbi from Montreal, Lavy Becker saw children in Pisa, Italy, run under their fathers' tallitot for the blessing, and he brought it home to his congregation.[23]

Orthodox Judaism does not permit a bat kohen (daughter of a kohen) or bat levi (daughter of a Levite) to participate in nesiat kapayim because the practice is a direct continuation of the Temple ritual, and should be performed by those who would authentically be eligible to do so in the Temple.

The Conservative movement's Committee on Jewish Law and Standards has approved two opposing positions: One view holds that a bat kohen may deliver the blessing; another view holds that a bat kohen is not permitted to participate in the Priestly Blessing because it is a continuation of a Temple ritual which women were not eligible to perform.[24]

Use in Christian Liturgy: Still a Priestly Blessing

The Priestly blessing is listed as Solemn Blessing #10 (Ordinary Time I) in the Roman Missal, and it is widely used in Anglican, Lutheran and other liturgical churches. Since only those ordained to consecrate the Eucharist (bishops and priests in the Catholic traditions and their equivalents in Protestant churches) are authorized to pronounce blessing (as opposed to asking for a blessing, as at a meal), it remains a "Priestly Blessing."

The version contained in the Roman Missal reads as follows:

Deacon or Priest: Bow your heads and pray for God's blessing.

Celebrant (with arms extended): May the Lord bless you and keep you.

Response: Amen.

Celebrant: May His face shine upon you and be gracious to you.

Response: Amen.

Celebrant: May He look upon you with kindness, and give you His peace.

Response: Amen.

Celebrant: May almighty God bless you, the Father, and the Son, + (making the sign of cross) and the Holy Spirit.

Response: Amen.

Deacon or Priest: The Mass is ended. Go in peace.

Response: Thanks be to God.

Pop culture

In the mid-1960s, actor Leonard Nimoy, who was raised in a traditional Jewish home, used a single-handed version of this gesture to create the Vulcan Hand Salute for his character, Spock, on Star Trek. He has explained that while attending Orthodox services as a child, he peeked from under his father's tallit and saw the gesture; many years later, when introducing the character of Mr. Spock, he and series creator Gene Roddenberry thought a physical component should accompany the verbal "Live long and prosper" greeting. The Jewish priestly gesture looked sufficiently alien and mysterious, and became part of Star Trek lore.[25] Nimoy later recorded an English translation of the blessing for Civilization IV; the recording is played when the player discovers the technology "Priesthood".

Bob Dylan's song "Forever Young" from the Planet Waves album uses the form and some content ("May God Bless and keep you...") of the Priestly Blessings.

Leonard Cohen ended his concert in Ramat Gan, Israel, on 24 September 2009, with the Priestly Blessing, i.e. reciting it in Hebrew.[26] As his name suggests, Cohen is halakhically a priest.

In the movie Deep Impact, the President of the United States, played by Morgan Freeman, recites the Priestly Blessing in a speech to the world. This speech announces to the world that a comet is approaching the world and will cause an E.L.E. (Extinction Level Event).

References

- ^ Nulman, Macy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Prayer (1993, NJ, Jason Aronson) s.v. Birkat Kohanim, page 109; Gold, Avi, Bircas Kahonim (1981, Brooklyn, Mesorah Publ'ns) pages 28-29

- ^ Numbers 6:23–27. Found in Parshat Naso, the 35th Weekly Torah portion of the annual cycle.

- ^ Gold, Avi, Bircas Kohanim (1981, Brooklyn, Mesorah Publ'ns) pages 90 & 94; Elbogen, Ismar, Jewish Liturgy: A comprehensive history (orig. 1913, Engl.transl. 1993, Philadelphia, Jewish Publ'n Society) page 64, citing Mishna, Megillah 4:4.

- ^ Gold, Avi, Bircas Kohanim (1981, Brooklyn, Mesorah Publ'ns) page 94; for this reason, the blessing is not performed in the afternoon service of a festival (as distinguished from a fast), Nulman, Macy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Prayer (1993, NJ, Jason Aronson) pages 109-110; Sperling, Abraham, Reasons for Jewish Customs and Traditions [Ta-amei Ha-Minhagim] (orig. 1890, Engl. transl. 1968, NY, Bloch Publ'g Co.) page 67 (citing Orakh Hayyim 129:1)

- ^ Gold, Avi, Bircas Kohanim (1981, Brooklyn, Mesorah Publ'ns) page 95; the length of the period depends on the deceased relation.

- ^ Gold, Avi, Bircas Kohanim (1981, Brooklyn, Mesorah Publ'ns) page 90; but a Kohen is required to recite the blessing only once in a day, so a Kohen may refuse a request to perform the blessing a second time in the same day.

- ^ Gold, Avi, Bircas Kohanim (1981, Brooklyn, Mesorah Publ'ns) pages 94-95.

- ^ Nulman, Macy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Prayer (1993, NJ, Jason Aronson) page 111, citing the Zohar, Naso 147b, and the Kohanim themselves preface the blessing with their own prayer, thanking God for commanding them "to bless his people, Israel, with love."

- ^ Nulman, Macy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Prayer (1993, NJ, Jason Aronson) page 111; The Orot Sephardic Weekday Siddur (1994, NJ, Orot Inc.) page 178; Elbogen, Ismar, Jewish Liturgy: A comprehensive history (orig. 1913, Engl.transl. 1993, Philadelphia, Jewish Publ'n Society) page 63 ("The priests did not begin on their own, but the precentor had to call out the blessing before them, and this custom has become so deeply rooted that it is regarded as a rule of the Torah. (citing Sifre, Numbers, sec. 39)"

- ^ cf. The Complete ArtScroll Siddur (Ashkenaz ed., 2nd ed. 1987, Brooklyn) page 923; Gold, Avi, Bircas Kohanim (1981, Brooklyn, Mesorah Publ'ns) pages 43 & 69.

- ^ Nulman, Macy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Prayer (1993, NJ, Jason Aronson) page 112; Elbogen, Ismar, Jewish Liturgy: A comprehensive history (orig. 1913, Engl.transl. 1993, Philadelphia, Jewish Publ'n Society) page 64; The Complete ArtScroll Siddur (Ashkenaz ed., 2nd ed. 1987, Brooklyn) page 295.

- ^ Nulman, Macy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Prayer (1993, NJ, Jason Aronson) page 110; Gold, Avi, Bircas Kohanim (1981, Brooklyn, Mesorah Publ'ns) page 95; The Orot Sephardic Weekday Siddur (1994, NJ, Orot Inc.) pages 178 & 181.

- ^ Nulman, Macy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Prayer (1993, NJ, Jason Aronson) page 110

- ^ Sperling, Abraham, Reasons for Jewish Customs and Traditions [Ta-amei Ha-Minhagim] (orig. 1890, Engl. transl. 1968, NY, Bloch Publ'g Co.) pages 62-63.

- ^ [1] בצפון ובכל מקום שנהגו לשאת-כפיים רק במוסף שבת

[2] - ^ Nulman, Macy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Prayer (1993, NJ, Jason Aronson) pages 109-110; Elbogen, Ismar, Jewish Liturgy: A comprehensive history (orig. 1913, Engl.transl. 1993, Philadelphia, Jewish Publ'n Society) pages 64-66.

- ^ Nulman, Macy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Prayer (1993, NJ, Jason Aronson) page 109; Gold, Avi, Bircas Kohanim (1981, Brooklyn, Mesorah Publ'ns) pages 37-38.

- ^ Nulman, Macy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Prayer (1993, NJ, Jason Aronson) pages 110-111, although the Zohar and the Vilna Gaon had distinct instructionson the leader turning to the left and right at certain words.

- ^ Nulman, Macy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Prayer (1993, NJ, Jason Aronson) pages 109-110; although Yom Kippur is a solemn occasion, by the Neilah service there is a sense of hope and optimism for Divine forgiveness.

- ^ Gold, Avi, Bircas Kohanim (1981, Brooklyn, Mesorah Publ'ns) page 41.

- ^ Gold, Avi, Bircas Kohanim (1981, Brooklyn, Mesorah Publ'ns) page 41.

- ^ Mayer Rabinowitz, Women Raise Your Hands, OH 128:2.1994a

- ^ Kol Haneshamah Sahabat Vḥagim, The Reconstructionist Press Wyncote PA 1994 p.348 (footnote 2)

- ^ Rabbis Stanley Bramnick and Judah Kagen, 1994; and a responsa by the Va'ad Halakha of the Masorti movement, Rabbi Reuven Hammer, 5748

- ^ 1983 television show "Leonard Nimoy's Star Trek Memories" This story was told by Nimoy on camera and repeated in somewhat abbreviated form in 1999 on the SciFi Channel "Star Trek: Special Edition" commentary for the episode "Amok Time". Again, the story was told by Nimoy on camera.

- ^ Leonard Cohen recites the blessing at the end of his concert in Israel; see also the video at 8:00

Further reading

- Rabbi Avi Gold, Bircas Kohanim: The Priestly Blessings: Background, Translation, and Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic, and Rabbinic Sources Artscroll Mesorah Series, 1981, 95 pages. ISBN 0-89906-184-2

- Hilchot Tefilla: A Comprehensive Guide to the Laws of Daily Prayer, David Brofsky, KTAV Publishing House/OU Press/Yeshivat Har Etzion. 2010. (ISBN 978-1-60280-164-6)

External links

- Reasons for the customs of the Priestly Blessings (Birchat Kohanim) from the Chabad.org Jewish Knowledge Base

- Priestly Blessing, from the Union of Reform Judaism

- www.cohen-levi.org procedure for the blessing of the kohanim (info on ceremony and picture of hand position for blessing—Orthodox perspective)

- Recording of the Priestly Blessing on the Zemirot Database

Jewish prayers ShacharitPreparationMizmor Shir (Psalm 30) · Barukh she'amar · Songs of thanksgiving · Psalm 100 · Yehi kevod · Hallel (Ashrei · Psalms 146, 147, 148, 149, 150) · Baruch Adonai L'Olam (Shacharit) · Vayivarech David · Atah Hu Adonai L'Vadecha · Az Yashir · Yishtabach

Core prayersConclusionTachanun · Torah reading1, 2, 3 · Ashrei · Psalm 20 · Uva letzion · Aleinu · Shir shel yom · Kaddish · Ein Keloheinu4

Mincha Maariv Shabbat / Holiday additions Psalm 19 · Psalm 34 · Psalm 90 · Psalm 91 · Psalm 135 · Psalm 136 · Psalm 33 · Psalm 92 · Psalm 93 · Nishmat · Shochen Ad · Hallel · Torah reading · Yom Tov Torah readings · Haftarah · Av HaRachamim · Mussaf · Birkat Cohanim6 · Anim Zemirot · Tzidkatcha · Al HaNissim

Seasonal additions Psalm 27 · Avinu Malkeinu · Selichot

Other prayers Amen · Modeh Ani · Ma Tovu · Adon Olam · Yigdal · Al Netilat Yadayim · Asher Yatzar · Birkat HaMazon · Havdalah · Kiddush Levana · Tefilat HaDerech

1 On Shabbat. 2 On holidays. 3 On Mondays and Thursdays.

4 Only on Shabbat and holidays, according to Nusach Ashkenaz in the diaspora. 5 On fast days. 6 Daily in Israel.Categories:- Jewish blessings

- Jewish services

- Hebrew Bible verses

- Torah

- Book of Numbers

- May the LORD (YHWH) bless you and guard you -

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.