- M. A. G. Osmani

-

Mohammad Ataul Ghani Osmany Born September 1, 1918

Sunamganj, Sylhet, BangladeshDied February 16, 1984 (aged 65)

London, EnglandBuried at Near the Shrine of Hazrat Shah Jalal (R), Sylhet, Bangladesh Allegiance  British India (till 1947)

British India (till 1947)

Pakistan (after 1947)

Pakistan (after 1947)

Bangladesh (Final Allegiance)

Bangladesh (Final Allegiance)Service/branch Bangladesh Armed Forces Years of service 1939-1947 British Indian Army

1947–1967 Pakistan Army

1971-1972 Bangladesh ForcesRank General Commands held 1st East Bengal Regiment

9/14 Punjab Regiment

EPR

Commander in Chief Bangladesh Armed Forces April 1971- April 1972Battles/wars World War II

Indo-Pakistan War of 1947

Indo-Pakistan War of 1965

Bangladesh Liberation War1971General Muhammad Ataul Ghani Osmany, popularly referred to as Bangabir General M.A.G. Osmany (Bengali: মুহাম্মদ আতাউল গনি ওসমানী; 1 September 1918– 16 February 1984) was the Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of Bangladesh Forces during the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971. He equally presided over the significant Bangladesh Sector Commanders Conference 1971 during which the entire Bangladesh Forces were authorized and created.

An officer with the British Indian Army since 1939, he served during WWII in Burma. His unit supported all plans of the Allied services as part of the Army Service Corps, rising to the rank of Major by 1942. He opted to join the Pakistan Army after British departed leaving the two new independent nations of India and Pakistan in 1947 as a Lieutenant Colonel. His career was checkered, he had disagreements with his superiors over issues regarding the unprofessional conduct and rules below norms that were practiced during recruitment and treatment of Bengali personnel during both British rule and to an extent also in Pakistan.

Osmany earned a reputation as a highly principled and honest officer, and retired as a Colonel in 1967 as the DDMO in GHQ Pakistan. A legend among Bengali servicemen for his willingness to stand up against higher command for legitimate concerns, his name carried honour and prestige. After retirement, he was welcomed into politics in his area under the leadership of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. He later joined the Awami League, and was elected MNA in the 1970 Pakistan general elections from Sylhet. During a meeting at Mujib's residence during late afternoon hours on 25 March 1971, Osmany, also one of many, advised Sheikh Mujib regarding the terrible plight that ensued, and to declare independence of Bangladesh through mass media and move to a secure location.

He was elected as C-in-C of Bangladesh Forces in 1971 by all the Bengali officers, who where the principal participants during the early inception of the independence declaration on March 26, 1971. This was ratified by Bangladesh Government in exile on April 10, 1971. In April 1972, General Osmany, the C-in-C, retired as the first full General (four star) of Bangladesh Forces, which was replaced by Bangladesh Army, Bangladesh Navy and Bangladesh Air Force. And three separate chiefs were selected on 7 April 1972 along with their Headquarters. Thus 'General M A G Osmany' is the only historical name whose name appears first in the honour boards of the three services as C-in-C between 12 April 1971 to 7 April 1972.

After serving in various government posts during 1972-1975 until his resignation, he was also active in politics during 1977-1984 as the head of Jatiya Janata Party until his death.[1]

Education

Osmany was born in Balaganj, Sylhet Division on 1 September 1918. He was a descendant of Shah Nizamuddin Osmany of Dayamir, who came to Sylhet with Hazrat Shah Jalal (R) in 1303. Their immediate family members live in the village of Dayamir. Osmany passed matriculation from Sylhet Government Pilot School in 1934, securing 1st division marks - which was a rare feat in those times. Like many Muslim Bengali students of the era, He attended Aligarh Muslim University, India and graduated in 1938. Osmany then registered for M.A. in geography at the same institution, also took the Indian Civil Service examination as per his father's wishes and passed. The advent of World War II saw Osmany shelf his civilian career plans for the military. This was probably the only time he went against the wishes of his father.

Military career

In 1939, Osmany started his military career as a Gentleman Cadet during rule under the British Empire in the Indian Military Academy at Dehra Dun. Upon completion of training, which lasted from July 1939 to October 1940, he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the British-Indian Army as an artillery officer in 1940. During World War II, he commanded an ASC (Army Supply Corps) unit, serving in the Burma front. Osmany was promoted to the rank of Captain in 1941 and received a battlefield promotion to the rank of Major in 1942 and at the age of 23, he was the youngest officer to hold that rank in the British Indian Army for some time. As a Major he commanded a Motor Transport battalion and after the war ended, Osmany was selected to attend the Staff Course in Quetta, Pakistan, and upon completion of the course in 1947, he was selected for promotion to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. As the British Empire dissolved with the birth of two nations of India and Pakistan in 1947, Osmany received his promotion soon after the new Pakistan Army was organised. Osmany witnessed the end of the British Indian army as an active organization. He was the main person who represented Pakistan during the division of military assets of two emerging countries - India & Pakistan.

Career in the Pakistani Army

After the birth of India and Pakistan in 1947 following the departure of the Lord Mountbatten, Governor General of British India, Osmany joined the newly formed Pakistan Army on 7 October 1947, and was soon promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. Being a career experienced officer and having served in WWII, he was immediately assigned to the General Staff Headquarters. He was appointed senior aide to the Chief of the General Staff in 1949. Later Osmany chose to take a temporary reversion to the rank of Major, when he decided to leave the A.S.C and join the Infantry of the army. During his stay at the Quetta staff college, he served alongside (then) Major Yahya Khan, Major Tikka Khan, and Major A. A. K. Niazi, all of whom ironically were destined to lead the Pakistan army against the Bangladesh Forces commanded by Osmany in 1971. After his re-induction training Major Osmany was commissioned in the infantry in May 1951 and repromoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. He was posted as 2IC and acting CO of 5/14 Punjab (5th Punjab Battalion of 14th Punjab Regiment), which was then part of a brigade commanded by Brigadier Ayub Khan, and did a tour of duty in Kashmir and Waziristan for four months.

Tour of duty in East Pakistan (1950–1956)

Lt Col Osmany was immediately posted as CO of 1st East Bengal Regiment, then stationed in Jessore, East Pakistan in October 1951. The GOC of East Pakistan at that time was Brigadier Ayub Khan, commanding the newly formed 14th Division, which only had two infantry battalions. Osmany was a hard taskmaster as CO of 1 EBR, and he implemented some fundamental changes that were to have a far-reaching effect on the character of the regiment and on his career path. He chose Bengali songs as the regimental marching and band songs ("Chal Chal Chal" by Kazi Nazrul Islam, "Gram Chara oi ranga matir path" by Rabindranath Tagore and Dhano Dhaney Pushpay Bhora by D.L. Roy), and introduced the Bratachari dance (introduced by Guru Shodoy Dutt) as the regimental dance.[2] These obvious displays of Bengali culture did not sit well with the Punjabi top brass, who were irked by this adoption of what was in their view Hindu culture.[citation needed] Osmany characteristically stuck to his guns, and stubbornly carried through the said reforms after the GHQ approved his suggestions. In doing this, he repeatedly clashed with the Punjabi chauvinists, notably General Ayub Khan, and began gaining reputation as a hard-nosed, stubborn officer with Bengali nationalistic inclinations.[citation needed] He also set up a tough training regime for the battalion, aiming to get the soldiers in top physical shape and the highest level of skill possible. Successive COs (both Bengali and non-Bengali) of the battalion built on the foundation he had laid, and the battalion went on to win a total of 17 gallantry awards in the Indo-Pakistan War of 1965, the highest number of awards won by any Pakistan Armed Force unit engaged in that conflict. 1 EBR was posted in the Lahore front under Lt Col. A.T.K Haque (Bengali), and one of the units it fought against was the 2nd Jat Regiment of the Indian Army.

In 1952, Osmany served as commanding officer of the 9th battalion of the 14th Punjab Regiment, and later as additional commandant of the East Pakistan Rifles. While serving in the EPR, he played a crucial role in opening up EPR recruitment for non-Bengali minority people (Chakma, Mogh, Tripura peoples, etc.) After his stint in the EPR (present Bangladesh Rifles now Bangladesh Border Guards), Osmany joined the East Bengal Regimental Center (EBRC) in 1954 and served for one year. Due to Osmany's superior OER (Officer Evaluation Report) the rank of Lieutenant Colonel came sooner than later. During this posting Osmany was promoted to Colonel in 1956 and joined the Pakistan Army GHQ at Rawalpindi in West Pakistan.

Last post: Staff officer GHQ Pakistan

By 1958 Osmany held the post of deputy director of the general staff and subsequently deputy director of military operations (DDMO) under Major General Yahya Khan and held that post until his retirement eight years later. During the first decade of his career he had reached the rank of Colonel, during the next decade Osmany was not destined to get a single promotion. His hard core principles, his fierce loyalty and integrity, and determination to improve the standards of all Bengali personnel in the Pakistan army and his willingness to take on anyone who differed with him earned him quite a degree of honour and prestige.

Bengali soldier recruitment bottleneck

Pakistan was left with 6 infantry divisions and one armoured brigade after the division of the British Indian army in 1947, although none of these formations were fully equipped or staffed at that time. The number of Bengali officers and soldiers in the newly formed Pakistan armed forces was small due to the British preference to recruit from so called Martial Races, and because many non Muslim Bengali personnel had opted to join the Indian Army after the British left. Pakistan army had raised only two battalions of East Bengal Regiment during 1947-1950, while a number of Punjab Regiments had been inherited from the British Indian Army. The Azad Kashmir Regiment was created soon after the Indo-Pakistan 1948 war.

When Osmany joined the GHQ in 1956, 3 East Bengal regiments and the East Bengal Regimental Center (EBRC) had come into existence within the structure of the Pakistan army. During the next 9 years, the number of Punjab Regiments (reorganized in 1956) reached almost 50, the Frontier Force Regiments (created 1957) and Baluch Regiments (created in 1957) were reaching the mid-40s, while the Azad Kashmir regiment was numbering in the 40s. Only 6 East Bengal Regiments had been created during the same time span. The reasons for this situation were:

- Many senior officers of the Pakistan army still believed in the Martial Race theory, and considered Bengalis to be poor soldier material.[3][4]

- The Bengali recruits were generally of smaller build than the West Pakistanis, and many failed to meet the then established minimum physical requirement of a recruit, which was set on average West Pakistani physical characteristics.[3]

- Many Pakistani officers favored creating mixed regiments instead of purely Bengali ones. Some Pakistani officers felt that increasing the number of exclusive Bengali formations was a threat to the unity of the army.[5]

Pakistani officers not swayed by the above facts were skeptical about the adaptability of Bengali soldiers in West Pakistani environment, where the bulk of Pakistani forces were concentrated according to the Pakistani strategy: Defense of East Pakistan lies in the West. The neglect of East Pakistan defense infrastructure was another bone of contention between Osmany and the Pakistani High command. In 1965 the Pakistani Army had 13 infantry and 2 armoured divisions in service, but only 1 under-strength infantry division was based in East Pakistan. Osmany fought with his seniors on these issues and was sidelined as a result. Colonel Osmany had served under (then) Brigadier Gul Hassan Khan in 1964, when he was the DDMO and Gul Hassan was the DMO. Although Brigadier Hasan was Osmany 's junior, he held the senior post. General Hasan had given a good confidential report about Osmany, and felt that Osmany was not given promotion despite having some excellent qualities. Gul Hassan allowed Osmani time to concentrated on issues concerning the Bengal regiments, partly to keep him occupied and partly because the top brass was bypassing Osmany .[6]

Osmany 's successor as DDMO was (then) Col. Rao Farman Ali - another person destined for infamy in Bangladesh in 1971. General Farman was reportedly horrified upon seeing how Osmany was treated in the Pakistan army. His office was totally run down, Osmany was kept out of the loop and purposefully neglected, even the office help treated him with disdain. Osmany had not been promoted because he was a Bengali and was deemed untrustworthy by the high command.[7]

Retirement and continued influence

Col. Osmany retired from Pakistani Armed Forces on 16 February 1967. Although his efforts had failed to increase the number of Bengal regiments, Pakistani High command, upon the recommendation of Lt. General Khwaza Wasiuddin, had put the existing regiments through a battery of exercises in West Pakistan to test their adaptability and combat readiness. Maj. Gen. Shaikh, evaluator of the exercises, had commented that the Bengali units had performed superbly and the proud Bengali soldiers took in representing East Pakistan was one key component of their success. He recommended against disbanding the units and raising mixed regiments.

Pakistani high command did not increase the number of Bengali units until after 1968, when following a pledge by General Yahya Khan, the number of Bengal regiments were increased to 10 and all new units were ordered to ensure at least 25% Bengali representation among the annual new recruits of the army.[8] Osmany, known as Papa Tiger continued to enjoy a positive, revered image among the serving Bengali rank and file in the Pakistan armed forces during his retirement, mainly because of his role in standing up for Bengali soldiers. Although he was not the most senior among Bengali officers (Maj. Gen. (ret.) S. Isfaqul Majid -commissioned after passing out of Sandhurst in 1924 holds this honor) nor did he reach the highest rank in the Pakistani army among Bengalis (Lt. General Khawza Wasiuddin holds that distinction), Osmany, along with Lt. General Wasiuddin (Colonel Commandant EBR) and Brig. M.H. Mozumdar (Commandent EBRC) were seen as the patron and guide for Bengali troops.[9]

Entry into politics

After his retirement, Osmany entered politics of East Pakistan. He joined the Sheikh Mujib-led Awami League in 1970. As a candidate from Awami League, he contested the election from the Balagaung-Fenchugaung area in Sylhet and was elected a member of the Pakistan national assembly. Osmany was not destined to serve as a MNA in the Pakistan assembly because after the commencement of Bangladesh Liberation War, he became a member of the Bangladesh provisional government-in-exile.

Leadership during Bangladesh Liberation War

Col. (ret.) Osmany and Maj. Gen. (ret.) Majid formed part of the team that advised the Awami League leadership on military issues during 1971. As the political crisis deepened in March, many serving Bengali officers of the Pakistan Armed Forces began looking to Bengali politicians for guidance, and Col. Osmany was selected as the coordinator of these clandestine meetings.

Possible Bengali Preemptive Strike?

In the days prior to the crackdown student and youth wings of Awami League had set up training camps countrywide and trained volunteers with the aid of Bengali Ansars/Mujahids and student cadets. Talk of “independence” was in full flow, despite the fact that Awami League leadership had refrained from declaring independence on March 7, 1971. Bengali ex-servicemen of Pakistan Armed forces had also held rallies to declare their support for Awami League. Serving Bengali officers and troops also kept in touch with the politicians, seeking advice and guidance during 1971 when the political situation was becoming uncertain and confrontational. Maj. Gen (ret.) S.I. Majid and Col (ret.) M.A.G Osmany allegedly designed a military plan of action, which broadly was:[10]

- Capture Dhaka airport and Chittagong seaport to seal off the province.

- EPR and Police to capture Dhaka city aided by Awami League volunteers.

- Cantonments were to be neutralized by Bengali soldiers.

Bengali officers had advised the sabotage of fuel dumps at Narayanganj and Chittagong to ground Pakistani air power and cripple armed force mobility.

Awami League leadership opted to try for the political solution[10] and did not endorse any action or preparation for conflict by Bengali soldiers prior to the start of the crackdown. Warnings by Bengali officers that the Pakistan army was preparing to strike were ignored, junior Bengali officers were told by their seniors not to act rashly and keep out of political issues.

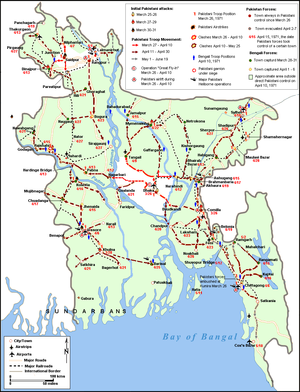

Despite all the political filibustering, public fanfare and alleged preparation for armed struggle, Pakistani army caught the Bengali political leadership and Bengali soldiers flatfooted. The resistance Pakistanis encountered country wide once Operation Searchlight was launched was spontaneous and disorganized, not a preplanned coordinated military response under a central command structure. In most cases Bengali soldiers were unaware of the situation around the country, many units continued to perform routine duties as late as March 31 and rebelled only after they came under Pakistani attack. Some Pakistani generals suggested declaring a general amnesty for Bengali troops upon observing the situation as early as March 31 (it was ignored).[11] Although warned of the departure of Yahia Khan and the movement of Pakistani troops, the declaration of independence by Mujibur Rahman on March 26 was given after the attack had commenced and was largely unnoticed (ironically Pakistanis picked it up).[12] No countrywide communication reached Bengali soldiers to start the uprising, Bengali troops and officers took the initiative to rebel upon being attacked or hearing the news of the Pakistani attack.

Role in Bangladesh Liberation War

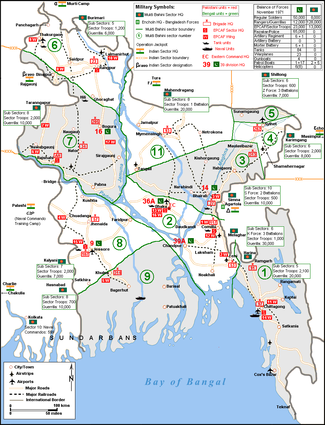

Col. Osmany was present at the house of Sheikh Mujib on 25 March 1971, when Bengali officers informed Awami League leaders of the departure of Yahya Khan and army movement.[13] After failing to persuade Sheikh Mujib to declare independence, amidst the rising chaos run by the Pakistani establishment, and relocate to a secure place, Osmany himself relocated to Sylhet during March 28–29, shaved off his famous mustache (he was often called the man attached to a mustache)[14] then made for the Indian border and reached the area under 2nd EBR control in Sylhet on April 4, 1971. A conference between senior Bengali officers and BSF representatives were held at Teliapara on the same day.[15] On April 10, Bengali Government in Exile at Agartola appointed Col. Osmany Commander of Bangladesh Forces. Osmany appointed 4 sector commanders: Maj. Ziaur Rahman (Chittagong area), Maj. Khaled Musharraf (Comilla Area), Maj. C.R. Dutta (Sylhet Region) and Maj. Abu Osman Chowdhury (Kushtia-Jessore). The following day 3 more sector commanders were chosen: Maj. Nazmul Huq (Rajshahi-Pabna), Captain Nawajish (Rangpur-Dinajpur) and Captain Jalil (Barisal).[16] Pakistan Army appointed Lt. Gen. A.A.K Niazi GOC East Pakistan on the same day. With the formation of Bangladesh government on 17 April 1971, retired Colonel Osmany was reinstated to active duty under the authority of Bangladesh government and appointed as Commander-in-Chief of all Bangladesh Forces. He was later promoted to the rank of full General during the 11–17 July Bangladesh Sector Commanders Conference 1971.

Initial Activities as CIC

General Osmany did not assume personal command of the Bangladesh Forces until after April 17, 1971. The existing Bengali fighting formations were located far away from each other, and lacking a proper command staff and more importantly a fully integrated communication network, exercising real-time command over the widely spread formations was impossible. Osmany instead chose to allow the designated sector commanders to fight on as they saw fit, while he toured the designated sectors, and met with Indian officials in New Delhi and Kolkata. He conferred Tajiuddin and along with spoke to Indian authorities on two points only. The two principle points were weapons and communications. Supplying weapons, ammunition and adequate communications gear was and remains the most expensive trade in any military. To the poorly equipped Indian army in 1971, such a notion was hardly affordable. The Indian officials with its meager resources had to deny any requests for weapons or communications. Furthermore communication supplies resulting in unaccounted for status would result in a serious problem. There was also a serious trust factors multiplied by the religion issue in the front lines. Indian army planners had very little idea or training on tough terrains of Bangladesh, which was just devastated by a severe cyclone. General Osmany along with most of his senior command staff was very knowledgeable and well trained obviously having served in East Pakistan. The Indian army inquired about Osmany's plans, understood the outlined the situation in Bangladesh, had assisted to organize the Bangladesh Forces structure and sounded out the possibility of open Indian intervention the ripe moment. However this came at Osmany's demise. Indian Army secretly negotiated a transfer of power of authority of Bangladesh Forces and the civilian militias Mukti Bahini which the Awami League leadership readily agreed to while Osmany was on inspection of the front lines in Kurigram during early November 1971. Osmani seriously argued that under no justification could such an action been done. He had argued that Indian units could very well serve with and under the built and organised leadership of Bangladesh Forces in their struggle. He seriously spat with the Awami League leaders for what intention would India want to take over the leadership of the Bangladesh struggle. He in protest never signed off his authority. He went off to the Sylhet sector and fought with the Z-Force during the last 3 weeks of the war.

The Bengali resistance had put up an unexpected stiff resistance and had managed to derail the initial Pakistani estimate of pacifying East Pakistan by April 10. However, the initial successes were not sustainable as the Bangladesh Forces needed continuous supply of ammunition and trained men, officers, coordination among scattered troops and the lack of central command structure, although a major advantage that was realised was that majority of the country was still outside Pakistani control. Pakistani army had airlifted the 9th and 16th infantry division to Bangladesh by April 10 and was poised to seize the initiative quickly but seriously miscalculated. Gen. Niazi, obtaining a brief from Gen. Raza (the departing GOC East Pakistan), implemented the following strategy:[17]

- Clear all the big cities of insurgents and secure Chittagong.

- Take control and open all river, highway and rail communication network.

- Drive the insurgents away from the interior of the country.

- Launch combing operations across Bangladesh to wipe out the insurgent network.

Rebuilding the Bengali forces

File:MAG Osmany Jeep.jpgThe Kaiser Willys Jeep Wagon used by Osmany to visit the war fronts during the war.During the period of April–June, General Osmany was busy with touring the various areas in an effort to boost morale and gather information, meeting with his Indian counterparts and setting up the Bangladesh forces command structure. The Indian army had taken over supplying the Mukti Bahini since May 15 and launched Operation Jackpot to equip, train, supply and advise Mukti Bahini. By mid June, Bengali fighters had been driven into India and was in the process of setting up infrastructure to run a sustained, coordinated guerrilla campaign. Bengali high command had begun to rebuilt and redeploy Mukti Bahini units since mid May,[18] and now began to tackle the task in earnest. During June –July, Mukti Bahini activity slacked off and the quality and effect of the insurgency was timid and poor.[19]

The task of planning and running the war was enormous, much more so because of the acute shortage of trained officers in the surviving Bengali forces. Of the 17,000 active duty Bengali soldiers (Army and EPR) who faced the Pakistani onslaught on March 25, 1971, about 4000 became prisoners,[20] and casualties had reduced the number of available trained personnel even further. Retired servicemen and new trainees had boosted that ranks somewhat, but further training and recruiting was needed to achieve the maximum possible results. Having lost the initial conventional war, but having secured Indian support and set up an infrastructure to run the war, the next step for the Mukti Bahini commanders was to come up with a comprehensive strategy with clearly defined roles and goals - something that also involved creating a substantial guerrilla force from scratch.

The July 10–15 sector commanders conference was to provide much needed guidance in this regard. The conference was chaired by Prime Minister Tajuddin Ahmed and coordinated by Gen. Osmany, and took place at 8, Theater Road, HQ of the Bangladesh Government in exile.

The Conference: Osmany Resigns

Col. Osmany was not present during the first day of the conference -he had resigned as CIC Bangladesh forces the previous day.[21] A group of Bengali officers had discussed an idea about creating a War Council, with Maj. Ziaur Rahman as its head and all the sector commanders as members to run the war effort - Osmany was to be the Defence Minister. Presented by Major Q.N. Zaman[22] and supported by Maj. Ziaur Rahman during a discussion session of all sector commanders, the officers feared that given the distance between sector headquarters and Kolkata and the poor state of communication, it might be better to have a separate operational wing to run the war effort to lessen the burden on Osmany. The facts were later probably misrepresented to Col. Osmany, who resigned as this proposal was not complementary to his leadership abilities or to his post as CIC.[21] The following day Osmany resumed his post as CIC after all sector commanders requested him to resume his post. The meeting went on without a glitch and decisions on strategy and organization was taken - all of which were vital for the War. The major decisions were:

- Designating the operational area, strength, command structure and role of the Mukti Bahini. General Osmany was to remain C-in-C, with Lt. Col. MA Rab (posted at Agartola with no combat duties) as the Chief of Staff (COS), Group Captain A.K Khandker was made the Deputy Chief of Staff (DCOS). Bangladesh was divided into 11 combat sectors, and individual sector commanders were selected or reconfirmed for each sector. Out of the 11 proposed sectors, 8 became organized and active by July, with sectors no 5 and 11 becoming active in August. Sector no 10 (encompassing all areas east of Teknaf and Khagrachari) was never activated.[23] and the proposed area of operation for this sector was incorporated in sector no 1. Later the naval commando unit activities were designated as 'Sector 10' and commanded by Osmany himself.

- Mukti Bahini personnel were divided into 2 broad subdivisions: Regular Forces, and Freedom Fighters.

Regular Forces: This contained the defecting Bengali soldiers and retired members of the Pakistan army and EPR troops. Organised into battalions, these later became known as Z Force, K Force and S Force brigades. Lack of trained regular troops meant majority of recruits were either ex EPR servicemen or newly trained recruits. Those trained men from regular army, EPR, police, Ansar/Mujahids not included in the regular formations were formed into sector troops - which were more lightly armed but operated as conventional force units. Army officers were in command of these detachments. Sector troops were not armed like the regular battalions, but received monthly salaries like their comrades.[24] The regular force personnel initially operated in the border areas.

Freedom Fighters: Also known as Gonobahini, the newly trained guerrillas were part of this organization. They were lightly armed, received no monthly pay and were deployed mostly inside Bangladesh upon completion of training.

- Political and civil organization for each sector as well as war objectives were also discussed and decided upon. Use of Guerrillas to hit the Pakistani armed forces, their collaborators, economic and logistical infrastructure was given priority.

Osmany as C-in-C: Leadership style

General Osmany was not a micro-manager who liked to run the day by day operations and delve on details of every plan being hatched by the sector commanders. He delegated much to the sector commanders, which gave them broad freedom of action but also increased their workload - often stretching their shorthanded sector staff beyond their limits.[21][24] On the other hand, given the distance between Kolkata and the sector Hqs and the absence of any direct links (communications had to be channeled through Indian army comm. system), General Osmany had little choice but to delegate. However, the absence of an integrated command structure made it impossible to implement a full fledged strategy timely -which was a weakness that remain unsolved.[25]

- General Osmany was not a micro manager obsessed with detail and control. He preferred the sector commanders to implement the broadly agreed on strategy as they saw fit. This gave them freedom of action but sometimes the lack of guidance from Bangladesh forces HQ, especially for resolving differences of opinion with the Indian sector officers, created unwanted tensions and delays.[26]

- A thoroughly professional soldier, Osmany lived a Spartan life, wore simple clothes, ate normal food and used camp furniture despite living in Kolkata during the war, setting up an example for his subordinates. A man of refined culinary tastes, he appreciated the meals served by Indian officers during their meetings but ever the gentleman, never insisted on this.[27] His style of living was exemplery for his subordinates in this regard[28]

- He did insist on maintain proper protocol while dealing with his Indian counterparts. As C-in-C Bangladesh Forces his position was equivalent to that of Sam Manekshaw, and his dealings with Lt. Gen. Jacob and Lt. Gen Aurora was according to this view and combined with his stubborn nature, made him a hard man to work with in Indian eyes.[29]

- Osmany was pragmatic enough to not to allow his insistence on protocol impede the war effort. He did not view Indians working through Group Captain A.K. Khandker, the deputy Chief-of-Staff (whom the Indians viewed as a pragmatic, polished officer with a practical approach[30] and clear grasp of strategy), as circumventing his authority.

- Having a brusque manner and a volatile temper, he was not above dressing down his subordinates in public – something that was resented by his subordinates. He also had a habit of discussing the legal frame of the future Bangladesh army or other issues not related to the war while touring the front – much to the bemusement and irritation of his fellow officers.

- He was against politicizing the Bangladesh forces and in this he had the full support of Tajuddin Ahmed, the prime minister.[31] He appointed officers on merit and not political affiliation. Although for security reasons only Awami league members were recruited initially for the Mukti Bahini, Osmany opened up the recruitment to all willing to fight for Bangladesh in September with the Prime Ministers approval and support. Sector commanders had recruited non Awami league member prior to this, and Osmany had turned a blind eye despite some of the commanders being branded as leftists and insubordinate by some political leaders.[32]

- Osmany was aware of his image and place in the Bangladesh forces and used it to his advantage. His ability and scope to solve the problems was limited by the extent of Indian support and Bangladesh government in exiles agenda. When confronted with a deadlock, he would often threaten to resign, which would almost always result in the others giving in – another reason some of his subordinates took exception to his leadership style. Only once was his bluff called – when he threatened to resign over placing Bangladesh forces under the Joint Command headed by Lt. Gen. J.S. Aurora, Tajuddin Ahmed agreed to accept if a written resignation was submitted. Gen. Osmani dropped the issue.[33]

Strategy for the Campaign

General Osmany decided on the strategy for Bangladesh forces to follow and liased with the Indian brass to keep them appriased of such decisions during July - December 0f 1971, and was not destined to organize an operation like the Tet Offensive or lead in a battle similar to Dien Bien Phu during his sting as C-in-C of Bangladesh forces. His leadership and strategy was a product of his professional career and the demands of the situation on the ground, which also influenced his leadership style to a large extent.He relied on his background of active participation in the South-East Asian sector during the Second World War. From May 15 the Indian army began to help build the liberation force.Major-General Sarker of the Indian Army was appointed as the Liaison Officer between Bangladesh Government-in-exile and the Indian Army.In the meantime Major Safiullah,Major Khaled Musharraf and Colonel Osmany met at Teliapara, a place in Sylhet district and prepared a basic paper on the strategy of the liberation war.[34] His differences with the Indian brass was to start with the selection of his initial battle strategy. Bangladesh government had hoped to raise a regular force of 30,000 soldiers and 100,000 guerrillas during 1971 - something which the Indians thought unrealistic.[35] There were also issues concerning the training, deployment and objectives of these forces where opinions between Bangladeshi and Indian leadership differed.

The initial Strategy (July - September 1971)

General Osmany was a conventional soldier with orthodox views and his initial strategy reflects his background. The uncertainty over the timing, scope and scale of direct Indian military intervention was another factor that influenced his decision. Osmany decided to raise a conventional force of regular battalions and use them to free an area around Sylhet, while organizing countrywide guerrilla activity as the secondery effort.[35][36] Bangladesh government in exile requested Osmany to make use of the one resource available in abandunce: manpower, and he did not object to the plan of sending thousands of guerrillas into Bangladesh with minimal training. It was hoped that some of the guerrillas would attain the level of expertise needed through experience.[37]

Two ways to skin a cat

The Indian planners were concerned with the quality and effectiveness of a force raised in haste. They were concerned that such a force would lack the trained junior leaders needed to run an effective campaign.[38] They had envisioned a force of perhaps 8,000 personnel with at least 3/4 months training (leaders receiving longer training), led by the surviving officer/men of the EBR/EPR[39] to commence operations in small cells inside Bangladesh by August 1971.[40] The raising of additional battalions only drained away potentail leadership candidates away from the guerrilla forces -undesirable for the Indian outlook.

General Osmany was stubbornly insistent, and his stubbornness did not sit well with the Indians - who thought deputy chief of staff A.K Khandkar was easier to work with.[41] However, Indians provided support in raising 3 additional battalions and 3 artillery battries, but also insisted that the raising guerrillas be given due attention, to which Osmany raised no objection. Indians and Osmany differed on the location of the Free area - Indians suggested Mymensingh, but Osmani opted for Sylhet. General Osmani got his way again. Thus while the EBR battalions made ready, Mukti Bahini began sending 2,000 - 5,000 guerrillas inside Bangladesh each month from July onwards. Mukti Bahini commanders had agreed to the following objectives for the guerrillas during the sector commanders meeting:[42]

- Increase Pakistani casualties through raids and ambushed by sending the maximum possible number of guerrillas in the minimum possible time inside Bangladesh.

- Cripple economic activity by destroying power stations, railway lines, storage depots and communication systems.

- Destroy Pakistani force mobility by blowing up bridges/culverts, fuel depots, trains and river crafts.

- The objective is to make the Pakistanis to spread their forces inside the province, so attacks can be made on isolated Pakistani detachments.

General Osmany, however, supported the Indian initiative for training Naval commandos, who were an elite unit trained as per the Indian doctorine, and achieved spectacular results during 1971, demonstrating that he was pragmatic enough to accept Indian suggestions. He took exception to the creation of Bangladesh Liberation Force, a stance supported by sector commanders and the Bangladesh government in exile.

Issues regarding Mujib Bahini

General Osmany was Commander in Chief of all Bangladesh forces, but a number of units were outside the control of Bangladesh forces HQ. Bengali fighters had raised several bands to fight the Pakistani opposition in various areas of Bangladesh (Kaderia Bahini, led by Tiger Siqqiqi of Tangail is the most famous), and these operated independently of Bangladesh HQ. Osmany spared little thought on them, but the so call Mujib Bahini became a major cause of concern for the Bangladesh government in exile establishment. The Leaders of the Mujib Bahini were initially given permission by General Osmany to recruit student and youth volunteers for the war, but in fact had become leaders of a fully organized, well armed and trained force, who allegiance was firstly to Sheikh Mujib and then to their own commanders, not to the Bangladesh government in exile.

No one doubted the skill of the Mujib Bahini or commitment of its members to Bangladesh or their patriotism. Trained by General Uban, an insurgency expert, this force operated under the direction of R&AW outside the Bangladesh forces chain of command and the knowlwdge of Bangladesh government. Mujib Bahini members were better trained[22] and better armed than their Mukti Bahini counterparts.[43] Bangladeshi government and military leadership were concerned because:

- Most of recruits of Mujib Bahini had been identified as potential future guerrilla leaders of Mukti Bahini, who had suddenly disappeared from the camps - which was first noticed by Mukti Bahini command in June 1971. Their recruitmnt into a separate force meant the loss of leadership potential for the Mukti Bahini.[44][45]

- Operating outside the command structure and knowledge of Bangladesh leadership, their activities, successful or otherwise, often hindered Mukti Bahini operations. They would often strike in areas without Mukti Bahini knowledge, bringing in unexpected Pakistani retaliation and unhinging Mukti Bahini plans for the area.

- Some of the activities of Mujib Bahini was creating misunderstanding and distrust in the field. Some of their members had tried to influence Mukti Bahini members to switch their allegiance, in cases had tried to disarm the guerrillas and some clashes had taken place between Mukti Bahini and Mujib Bahini members, and in some areas Mukti Bahini sector commanders arrested known Mujib bahini members. The Indian Army and other organizations involved in supporting the Bengali resistance were also dissatisfied with the activities of this independent organization which was operating outside the existing chain of command.[46]

Bangladesh Government in exile took various diplomatic initiatives, including approaching RAW director Ramnath Kao[47] to bring this organization under the control of the government or under General Osmany without success. By August it was clear the independent activities of Mujib Bahini was detrimental for the war effort and Gen Osmany threatened to resign unless they were brought within the command structure of Bangladesh forces.[48] A meeting with D.P Dhar on August 29 produced an assurance that Mujib Bahini would inform of their activities beforehand to the sector commander prior to commencing their operations. Another meeting with Ramnath Kao on September 18 produced nothing about R&AW relinquishing their control over Mujib Bahini.

On October 21, Bangladesh Prime Minister Tajuddin Ahmed met with Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and she ordered D.P Dhar to solve the issue, who in turn informed Lt. Gen. B.N. Sarkar to meet with Mujib Bahini leaders and take necessary steps. Mujib Bahini leaders failed to show up, but sensing which way the wind was blowing, stopped their disruptive activities. Mujib Bahini, along with the Special Frontier Force under the command of Maj. Gen. Uban, went on to liberate Rangamati in December and helped the Indians dismantle the Mizo insurgent network.

Action and Reaction: June - September 1971

Pakistan army, after expelling the Mukti Bahini from Bangladesh, had enjoyed a relatively peaceful time between June and July 1971. Mukti Bahini activities had slacked off during the months of preparation, and although the Indian army had begun shelling border outposts (about 50% of the existing 370 were destroyed by the end of July)[49] to ensure easier infiltration into occupied territoties. Bengali regular forces were not ready for operation until mid July. With the conflict largely polarized around the India-East Pakistan border region, Pakistan Eastern command began reorganizing their forces to consolidate their control of the province. The following strategic and tactical steps were taken:[50]

- Pakistan Army deployed the 9th Division (CO Maj. Gen. Shaukat Riza, HQ Jessore, containing the 57th and 107th brigades, which were part of the 14th division prior to March 25) to operate in the area south of the Padma and West of the Meghna Rivers. The 16th Division (CO Maj. Gen. Nazar Hussain Shah, containing the 23rd (formally of the 14th division), 34th and 205th brigades) was responsible for the area north of the Padma and west the Jamuna rivers. The 14th Division (CO: Maj. Gen. Rahim. Khan, HQ: Dacca, containing the 27th, 303rd and 117th brigades, formally of the 9th division, and the 53rd brigade) looked after the rest of the province.

- The E.P.C.A.F (East Pakistan Civil Armed Force – 23,000 troops[51] with 17 operational wings[52]) was raised from West Pakistani and Bihari volunteers. Razakars (50,000), Al-Badr and Al Shams (5,000 members from each unit)[53] were organized from collaborating Bengali people. Many of the imprisoned EPR and Army troops were screened and absorbed into the Razakar organization.

- Shanti Committees were formed rally public support and provide leadership to Bengalis collaborating with the Pakistani authorities. The police force was reorganized, 5000 police was flown in from West Pakistan[54] and several civilian bureaucrats were posted to run the civil administration.

This vast organization was employed to control the province with an iron fist. Pakistani authorities decided to continue the terror campaign,[55] and rejected all call for political compromise and general amnesty, and did nothing to assuage the feeling of the Bengali population suffering under the army occupation.[54]

Strategically, the army deployed in all the sensitive towns, while the other para military units were deployed around the country. The EPCAF took over the duties of the defunct EPR – border and internal security. Pakistani forces occupied 90 Border Out Posts (BOPs) that were deemed crucial, out of 390, half of which had been destroyed by Indian shellfire by July end.[49] Often ad hoc units were created by mixing EPCAF and Razakars around a skeliton army formation for deployment in forward areas.[56] Pakistan army probably enjoyed their most peaceful period during the occupation of Bangladesh in 1971 between Late May and mid July, when Mukti Bahini was reorganizing and the Indian army was implementing Operation Jackpot in their support. From their bases the army conducted sweep and clearing operations in the neighboring areas to root out insurgents and their supporters. In absence of a fully fledged logistical system, the troops were ordered to live off the land – abuse of which led to widespread looting and arson. With the insurgency in its infancy – Pakistani army was most active during the months of April to June.

Mukti Bahini Response: The Monsoon Offensive

Mukti Bahini commanders had agreed to the following objectives during the sector commanders meeting :[57]

- Increase Pakistani casualties through raids and ambushed by sending the maximum possible number of guerrillas in the minimum possible time inside Bangladesh.

- Cripple economic activity by hitting power stations, railway lines, storage depots and communication systems.

- Destroy Pakistani mobility by blowing up bridges/culverts, fuel depots, trains and river crafts.

- The objective is to make the Pakistanis to spread their forces inside the province, so attacks can be made on isolated Pakistani detachments.

As Bengali guerrillas began to increase their numbers and activities inside Bangladesh from June onwards, sending 2000 – 5000 guerrillas across the border and began to become more active in the border areas, Pakistani army also began to adapt to the situation. Razakars and EPCAF were employed to deal with the internal security matters. Pakistan forces, unable to match the Indians shell for shell, declined to take up the challenge, relying on sudden barrages at selected areas. Choosing not to defend all the border outposts, Pakistani forces occupied and fortified 90 strategically located BOPs, while over half of 390 BOPs were eventually destroyed by Indian shellfire by July end to make Mukti Bahini infiltration easier. Pakistanis also build up an intelligence networks to collect information on Mukti Bahini activity and sent informers across the border to give early warning of Mukti Bahini activity.[58][59] Denied permission to launch cross border preemptive strikes, ambushes were laid for Mukti Bahini infiltrators and artillery was used to interdict movement whenever possible. Time consuming efforts were made to defuse mines, a favorite Mukti Bahini weapon. The Mukti Bahini activity was viewed as timid and the main achievements were blowing up of culverts, minimg abandoned railway tracks, and harassment of Pakistani collaborators.[19] Bengali regular forces had attacked BOPs in Mymensingh Comilla and Sylhet, but the results were mixed. Pakistani authorities concluded that they had successfully contained the Monsoon Offensive, and they were not far from the truth.[60][61]

Silver Linings among dark clouds

The sector commanders reviewed the results of the Mukti Bahini activities during June – August 1971, and General Osmany also conducted an overall assessment in September 1971. The findings were not encouraging; Mukti Bahini had failed to meet the expectations. The reasons for this were numerous and had to be properly handled to get the war effort on course. The main reasons identified were:

- The guerrilla network was being built and had not taken firm root in Bangladesh. Guerrillas, with only 3/4 weeks of training, lacked the experience and numbers to compensate their lack of skills. In many cases, they drifted back towards the border after a few days of operations or when under pressure from Pakistani forces.[62]

- Razakar and Shanti Committees were effective in countering the Mukti Bahini activity. About 22,000 better armed Razakars had become such a threat that in some areas Mukti Bahini ceased operating, and in other areas they were forced to operate against the Razakars, which suited the Pakistanis as it kept their forces from harm.

- Uncertainty over re-supply and maintenance had caused many of the Guerrillas cautious, they were unwilling to use up their scanty ammunition, which also hampered operations.[63]

- Until the ‘’Crack Platoon’’ members hit targets in Dhaka and the naval commandos simultaneously mined ships in Chittagong, Chandpur, Narayanganj and Mongla on August 15, the slow pace of operations inside Bangladesh was demoralizing for all involved – the Bangladesh issue was losing ground in the international arena[64]

- Bengali regular troops had attacked the BoPs with spirit, but more training, better communication and coordination with Indian army support elements were needed for launching a successful conventional campaign. The attack on Kamalpur by 1st EBR was a bloody repulse, 3rd EBR attack on Bahadurabad was a success. Likewise, attacks by 2nd, 11th 4th EBR yielded mixed results that only confirmed the conclusion.[65]

- Coordination between Indian forces and Bangladesh forces were poor, there were several incident of misunderstanding and the supply situation needed major improvement. In some areas relationship between Bengali and Indian commanders had degraded to the point of finger pointing[66] and in many cases conflicting messages had come to Indian and Bengali formations regarding the same operation.[67] These issues had further eroded the combat capacity of the Bengali forces on the ground during June - August 1971.

The one two punch

The failure of the so called monsoon offensive caused Bangladesh forces high command to rethink their strategy. Since the Bengali regular brigades (Z,K and S forces) were not ready to liberate and hold a lodgement area on their own, and there were several issues with the ongoing gureeilla campaign, it was clear a long struggle awaited the Bangladeshi resistance which could be cut short with a direct Indian military intervention – which was still uncertain. Several factors changed prior to Bangladesh High Command implementing the next strategy.

- The uncertainty over Indian involvement changed – after a meeting between Indian and Bangladesh Prime ministers in October it became clear India was likely to intervene sometime between December 1971 and April 1972.

- The Indian –Soviet Friendship pact assures India of superpower support – and enhanced Indian capability to supply the Mukti bahini as Russia began to send their WWII vintage surplus weapons to India.

- The Indian Army Eastern Command began to improve their logistical network from July 1971,[68] which also enabled getting supplies to the Mukti Bahini easier. Major General B.N. Sarkar of Indian army began coordinating the war objectives[69] for Mukti Bahini after consulting with Indian and Bengali officers on the ground and Bangladesh Forces HQ, and distribute the same set of objectives monthly to all concerned. This eliminated the misunderstandings and coordination problems between the Mukti Bahini and the Indian army to a large degree.

- At the beginning of the war Indian authorities officially endorsed only Awami League affiliated volunteer training, after the Soviet-Indian friendship pact for security reasons as India had security issues with some of their domestic left parties activities. After the Soviet-Indian pact, Prime Minister Tajuddin Ahmed opened up recruitment to all comers.

Initially, General Osmany thought about dismantling the regular battalions operating under Z, K and S forces and sending platoons from these forces to aid the guerrillas. His associates advised against this and he ultimately let them be, but deployed the Z force battalions separately to aid guerrilla actions around Sylhet. It was decided to senr at least 20,000 trained guerrillas into Bangladesh from September onwards. If even 1/3 of the force succeeded in it’ objective, the effect on the Pakistani forces would be devastating.

Effectiveness and importance

From August onwards the quality, number and effectiveness of Mukti Banhini operations showed a marked improvement. Armed convoys were ambushed, police stations attacked, vital installations were destroyed. From October onwards Mukti bahin became active bot on the border and inside Bangladesh to such degree that Pakistani resources were stretched and morale diminished to counter them.[19]

Despite the limitations and challenges rising from the state of the Indian transport system (training camps were located inside India), remoteness of the guerrilla bases, unavailability and inadequacy of proper supplies,[70] and the decision of Bangladesh High Command to put the maximum number of guerrillas into battle in the minimum time possible (often after 4 to 6 weeks of training, sometimes resulting in only 50% of the personnel receiving firearms initially),[71] the 30,000 regular soldiers (8 infantry battalions, and sector troops) and 100,000 guerrillas that Bangladesh eventually fielded in 1971 managed to destroy or damage at least 231 bridges, 122 railway lines and 90 power stations,[72] while killing 237 officers, 136 JCOs/NCOs and 3,559 soldiers,[73] of the Pakistan army and an unspecified number of EPCAF and police and an estimated 5,000 Razakar personnel[74] during the period of April–November 1971, the majority of which occurred after September. The Mukti Bahini efforts also demoralised the Pakistani Army to the extent that, by November, they left their bases only if the need arose.[72]

The Naval commandos had managed to sink or damage 15 Pakistani ships, 11 coasters, 7 gunboats, 11 barges, 2 tankers and 19 river craft.[75] Logistics was becoming a serious problem, of the minimum 600 tons needed by the Pakistan army daily, Mukti Bahini activity was hampering a substantial portion from going through.[76]

Against this move the Pakistani high command decided not to yield any territory and deploy their forces along the whole border. The grouping and regrouping of forces to secure the border and deal with the Mukti Bahini inside Bangladesh led to a loss of cohesion among Pakistani units, especiall among the infantry, artillery and mortar regiments. The loss of maneuverability exposed them to a one dimensional battle.[77] This stretched them thin without any effective reserves, and they became vulnerable to selective Indian and Bengali strikes when the Undeclared War started from mid November. The prolonged exposure and steady casualties also sapped morale and reduced the effeciveness of the troops considerably.

Post-independence activities

General Osmany held the title of Commander-in-Chief until his retirement in April 1972 at the old 14 division head quarters of the Pakistan Army in Dhaka Cantonment, when the Bangladesh Forces officially dissolved during the final Sector Commanders Conference into three independent regular forces, the Bangladesh Army, the Bangladesh Navy, the Bangladesh Air Force and the creation of Bangladesh Rifles. After the country's independence, Osmany retired from service 7 April 1972. He was then included in the cabinet of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as Minister of Shipping, Inland Water Transport and Aviation. Osmani was elected a member of the national parliament in 1973, and was included in the new cabinet with charge of the ministries of Post, Telegraph and Telephone, Communication, Shipping, Inland Water Transport and Aviation.

He resigned from the cabinet in May 1974 after the introduction of a one-party system of government through the Fourth Amendment to the constitution. Along with Barrister Mainul Hosein, both elected MPs resigned from the Awami League, protesting the total abolition of democracy in Bangladesh by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

M.A.G. Osmany was appointed an Adviser to the President in charge of Defence Affairs by Khondaker Mostaq Ahmed (then President and Law Minister currently) on 29 August 1975, but he resigned immediately after the killing of four national leaders inside the Dhaka Central Jail on 3 November.

The Jatiya Janata Party

Osmany launched a new political party styled as Jatiya Janata Party in September 1976 and was elected its President. He contested in the presidential elections in 1978 as a nominee of the Democratic Alliance. He contested in the presidential elections once again in 1981 as a nominee of the Jatiya Nagarik Committee (National Citizens Committee).

Family life

Osmany lived as a bachelor throughout his life and had no offspring who exist today. His family home is 18 km south from Sylhet City in the village of Dayamir now renamed as Osmany Nogor. His home in the Nayarpul locality of the north-eastern city of Sylhet, from where he hails, is currently a museum - Osmany Museum.

Though a bachelor all his life, Osmany was close to his relatives and family throughout his life. Most trips to Sylhet involved making visits to loved ones, and in Dhaka he would regularly welcome nephews and nieces to his residence. Within the wider family, Osmany was known for his love, but also for his temper, his passion, his glaring eyes and his military discipline. Only his Alsatians were generally disliked, and almost universally feared by visiting folk. Famously, one niece was bitten when she tried to run away from one of the Osmany Alsatians.

Death

In 1983, aged 65, Osmany was diagnosed with cancer at the Combined Military Hospital (CMH) in Dhaka. He was immediately flown to London for treatment, at the Government's expense. He was attended to by specialists at St Bartholomew's Hospital. Most of his time in the UK was spent staying at the family home of his nephew and niece, Mashahid Ali and Sabequa Chowdhury. Both were beloved to him - the late Mashahid (Shahee) had helped Osmany in his later years by funding the establishment of his political party, the Jatiya Janata Party, following Osmany 's exit from the Mujib government. Sabequa spent formative years of her childhood in Osmany 's home in Sylhet, and Osmany gifted his allocated plot in Dhaka to her in the early 1970s. Osmany 's days would pass with an almost endless stream of visitors, well wishers and acolytes calling on him to wish him well, to ask his guidance, or just to see him.

Though Osmany was responding favourably to the cancer treatment, in early February he deteriorated unexpectedly. The hospital diagnosed that he had been given the wrong type of blood at the CMH and that this was now infected. His demise followed immediately after, in bed on 16 February 1984 in London, aged 66. Throughout these months of treatment and convalescence, the famous fire in his eyes and the quiver in his bristly moustache stayed with him until the very end.

Following his sudden death, Osmany 's body was flown to Bangladesh. The cavalcade of cars to Heathrow was provided with a special police escort which, with full diplomatic protocol, sped the entourage through the streets of London, stopping the traffic along the route. About a days after his death Osmany was buried in Darga, Sylhet with full military honours. His grave lies adjacent to his mother's.

Remembrance

Mohammed Ataul Ghani Osmany is regarded in Bangladesh as one of the greatest leaders and heroes of the nation's freedom fighters, and regarded as a brave man (Bonga Bir) never afraid of laying down his life. Under his command, the organisation and conduct of Bangladesh Armed Forces came into being without whom it would have been very difficult. The international airport in his hometown of Sylhet has been named after him as Osmani International Airport(Osmani Antorjatik Biman Bondor ). Even the state-run hospital in Sylhet is named after him, as Osmani Medical College and Hospital. Also a small flock of tourists and local visitors flock to his dilapidated home in Dayamir, Sylhet to have a picnic on the huge lawn, a swim in the vast pond dug by himself, or just to admire the dilapidated house. Recently the Bangladesh Armed Forces headquarters authorised funds along with the Ministry of Liberation War Affairs for a complete renovation of his home and add more memorabilia. Every year, Osmani associations gather to hold huge ceremonies and functions, including engaging in televised discussion of General Osmany 's contributions. Also the medical college situated in Sylhet is named after him, Sylhet MAG Osmany Medical College.

See also

- Liberation war of Bangladesh

References

- ^ Raja, Dewan Mohammad Tasawwar, O GENERAL MY GENERAL (Life and Works of General M A G Osmany), p35-109, ISBN 978-984-8866-18-4

- ^ Raja, Dewan Mohammad Tasawwar, O GENERAL MY GENERAL (Life and Works of General M A G Osmany), p 62, ISBN 978-984-8866-18-4

- ^ a b Library of Congress studies.

- ^ Military, State and Society in Pakistan by Hasan-Askari Rizvi, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 0-312-23193-8 (Pg 128).

- ^ Salik, Siddiq, 'Witness to Surrender' p10, ISBN 984-05-1373-7

- ^ Hassan Khan, Lt. General Gul, 'Memories of Lt. General Gul Hassan', p265-267, ISBN 0-195-47329-9 | Bengali Translation: ‘Pakistan Jokhon Bhanglo’ University Press Ltd. 1996 ISBN 984-05-0156-9

- ^ Khan, Maj. General Rao Farman Ali, 'How Pakistan Got Divided', p12 | Bengali Translation: ‘Bangladesher Janmo’ University Press Ltd. 1996 ISBN 984-05-0157-7

- ^ Salik, Siddiq, Witness to Surrender p10, ISBN 984-05-1373-7

- ^ Salik, Siddiq, ‘’Witness to Surrender’’ p11

- ^ a b Salik, Siddiq, Witness to Surrender, p64

- ^ Khan, Maj. Gen. Rao Farman Ali, How Pakistan Got Divided, p93

- ^ Salik, Siddiq, 'Witness to Surrender', p75

- ^ Salik, Siddiq, Witness to Surrender, p70

- ^ Salik, Siddiq, 'Witness to Surrender', p12

- ^ Shafiullah, Maj. Gen. K.M., Bangladesh At War, p90, ISBN 984-401-322-4

- ^ Shafiullah, Maj. Gen. K.M., Bangladesh At War, p90, p110, ISBN 984-401-322-4

- ^ Niazi, Lt. Gen. A.A.K, The Betrayal of East Pakistan, p92-93

- ^ Islam, Maj. Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions, p211

- ^ a b c Salik, Siddiq, Witness to Surrender, p100

- ^ Hamoodur Rahman Commission Report, Part I, Chapter VI, para II

- ^ a b c Hasan, Moyeedul, Muldhara 71, p50

- ^ a b Shafiullah, Maj. Gen. K.M, Bangladesh at War, p161-162

- ^ Shafiullah, Maj. Gen. K.M, Bangladesh at War, p162-163

- ^ a b Islam, Maj. Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions, p231-232

- ^ Hasan, Moyeedul, Muldhara 71, p51

- ^ Hasan, Moyeedul, Muldhara 71, p52, p56

- ^ Jacob, Lt. Gen. JFR, Surrender at Dacca, p43

- ^ Islam, Major Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions p222

- ^ Hasan, Moyeedul, Muldhara 71, p54

- ^ Jacob, Lt. Gen. JFR, Surrender at Dacca, p44

- ^ Hasan, Moyeedul, Muldhara 71, p26

- ^ Islam, Major Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions, p223

- ^ Hasan, Moyeedul, Muldhara 71, p155

- ^ ^Muniruzzaman,Talukder, The Bangladesh Revolution And It's Aftermath, p107 ,ISBN-984-05-10975

- ^ a b Jacob, Lt. Gen JFR, Surrender at Dacca: Birth of A Nation, p43-44

- ^ Hasan, Moyeedul, Muldhara 71, p53-55

- ^ Islam, Maj. Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions, p234-233

- ^ Jacob, Lt. Gen JFR, Surrender at Dacca: Birth of A Nation, p43

- ^ Jacob, Lt. Gen JFR, Surrender at Dacca: Birth of A Nation, p93

- ^ Jacob, Lt. Gen JFR, Surrender at Dacca: Birth of A Nation, p90

- ^ Jacob, Lt. Gen JFR, Surrender at Dacca: Birth of A Nation, p44

- ^ Islam, Major Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions, p227

- ^ Islam, Maj. Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions, p278

- ^ Islam, Maj. Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions, p276

- ^ Shafiullah, Maj. Gen. K.M, Bangladesh at War, p161-163

- ^ Islam, Major Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions p279

- ^ Hasan, Moyeedul, Muldhara 71, p71

- ^ Hasan, Moyeedul, Muldhara 71, p72-74

- ^ a b Hasan, Moyeedul, Muldhara 1971, p45

- ^ Salik, Siddiq, Witness To Surrender, p92

- ^ Niazi, Lt. Gen AAK, The Betryal of East Pakistan, p105-106

- ^ Jacob, Lt. Gen. JFR, 'Surrender at Dacca,: Birth of a Nation, p189

- ^ Salik, Siddiq, Witness to Surrender, p105

- ^ a b Salik, Siddiq, Witness to Surrender, p96

- ^ Salik, Siddiq, Witness to Surrender, p94

- ^ Quereshi, Hakeem A., The 1971 Indo-Pakistan War: A Soldiers Narrative p95, 111

- ^ Islam, Maj. Rafiqul, ‘A Tale of Millions’ p227

- ^ Quereshi, Maj. Gen. Hakeem A, Indo Pak War of 1971, p108 – p110

- ^ Islam, Maj. Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions p284

- ^ Ali, Mag. Gen. Rao Farman, When Pakistan Got Divided’’, p100

- ^ Niazi, Lt. Gen. A.A.K, The Betryal of East Pakistan, p96

- ^ Jacob, Lt. Gen. JFR, Surrender at Dacca p94

- ^ Islam, Maj. Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions p292

- ^ Islam, Maj. Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions, p274, p292

- ^ Islam, Maj. Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions p297

- ^ Hasan, Moyeedul, Muldhara 71, p114

- ^ Islam, Rafiqul, A Tale of Millions, p236

- ^ Jacob, Lt. Gen. JFR, Surrender at Dacca, p78-79

- ^ Hasan, Moyeedul, Muldhara 71, p111-112

- ^ A Tale of Millions, Islam, Major Rafiqul Bir Uttam, p 215

- ^ A Tale of Millions, Islam, Major Rafiqul Bir Uttam, p 288

- ^ a b Witness To Surrender, Salik, Brigadier Siddiq, p 101

- ^ Witness To Surrender, Salik, Brigadier Siddiq, p 118

- ^ Witness To Surrender, Salik, Brigadier Siddiq, p 105

- ^ Jacob, Lt. Gen. JFR, Surrender at Dacca, p91

- ^ Hollingworth, Clare, The Daily Telegraph, Nov1, 1971

- ^ Khan, Maj. Gen. Fazle Mukim, Pakistan's Crisis in Leadership p128

Further reading

- Hasan, Moyeedul (2004). Muldhara' 71. University Press Ltd.. ISBN 984-05-0121-6.

- Salik, Siddiq (1997). Witness to Surrender. ISBN 9-840-51374-5.

- Jacob, Lt. Gen. JFR (2004). Surrender at Dacca: Birth of A Nation. The University Press Limited. ISBN 9-840-51532-2.

- Qureshi, Maj. Gen. Hakeem Arshad (2003). The Indo Pak War of 1971: A Soldiers Narrative. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-579778-7.

- Islam, Major Rafiqul (2006). A Tale of Millions. Ananna. ISBN 9-844-12033-0.

- Shafiullah, Maj. Gen. K.M (2006). Bangladesh at War. Agamee Prakshani. ISBN 9-844-01322-4.

- Rahman, Md. Khalilur (2006). Muktijuddhay Nou-Abhijan. Shahittha Prakash. ISBN 9-844-65449-1.

- Mukul, M. R. Akthar (2004). AMI Bijoy Dekhechi. Sagar Publishers. ISBN 9-844-5200-5.

- Niazi, Lt. Gen A.A.K (1998). The Betrayal of East Pakistan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-77727-1.

- Hassan Khan, Lt. gen. Gul (1978). memories of Lt. Gen Gul Hassan Khan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-47329-9.

- Ali Khan, Maj. Gen Rao Farman (1992). How Pakistan Got Divided. Jung Publishers.

- Raja, Dewan Mohammad Tasawwar (2010). O GENERAL MY GENERAL (Life and Works of General M A G Osmany). The Osmany Memorial Trust, Dhaka, Bangladesh. ISBN 978-984-8866-18-4.

External links

- Banglapedia article on Osmany

- The Daily Star article on Osmany

- Ekatture Uttar Ronangaon - ISBN 984-626-47-2

- Ministry of Defense Gazette Notification No.8/25/D-1/72-1378, Dated 15 December 1973.

- http://openlibrary.org/books/OL24597467M/O_General_My_General_-_Bangabir_General_M_A_G_Osmany

Military of Bangladesh Military history · Bangladesh Forces · Military academy · UN peacekeeping force · Bengal Regiment · Intelligence community (DGFI) · President Guard Regiment (PGR) · Senior Tigers · East Bengal Regiment · Cadet Colleges · Armed Forces DayWars and conflictsWar leadersM.A.G. Osmany · Ziaur Rahman · M. Hamidullah Khan · Khaled Mosharraf · Shafat Jamil · Abu Osman Chowdhury · M A Jalil · Abul Manzur · Nazmul Huq · K M ShafiullahDecorationsCategories:- 1918 births

- 1984 deaths

- People from Sunamganj District

- Generals of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

- Generals of the Bangladesh Liberation War

- Bangladeshi military personnel

- Aligarh Muslim University alumni

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.