- Yasujirō Ozu

-

Yasujirō Ozu

Born December 12, 1903

Tokyo, JapanDied December 12, 1963 (aged 60)

Tokyo, JapanOccupation Film director Years active 1929 – 1963 In this Japanese name, the family name is "Ozu".Yasujirō Ozu (小津 安二郎 Ozu Yasujirō, 12 December 1903 – 12 December 1963) was a prominent Japanese film director and (sometimes under the name James Maki) script writer. He is known for his distinctive technical style, developed during the silent era. Marriage and family, especially the relationships between the generations, are among the most persistent themes in his body of work. His outstanding works include Early Summer (1951), Tokyo Story (1953), and Floating Weeds (1959).

Ozu's reputation outside his native Japan has grown steadily since his death. Influential monographs by Donald Richie, Paul Schrader and David Bordwell have ensured a wider appreciation of Ozu's style, aesthetics and themes in the West.

Contents

Biography

Ozu was born in the Fukagawa district of Tokyo. At the age of ten, he and his siblings were sent by his father[1] to live in his father's home town of Matsuzaka, Mie Prefecture, where he spent most of his youth. He was educated at a boarding school but spent much of his time in the local cinema rather than a classroom.

He worked briefly as a teacher before returning to Tokyo in 1923 to join the Shochiku Film Company.

Ozu was well known for his drinking. In fact, he and his fellow screenwriter Kogo Noda used to measure the progression of their scripts by how many bottles of sake they had drunk. Occasionally visitors to his grave pay their respects by leaving cans and bottles of alcoholic drink. Ozu remained single and childless all of his life and stayed alone with his mother who died less than two years before his own death.

Ozu died in 1963 of cancer on his 60th birthday. His grave at Engaku-ji in Kamakura bears no name—just the character mu ("nothingness").[2]

Career

Ozu was initially hired as an assistant cameraman. He became an assistant director within three years, and directed his first film, Zange no Yaiba (The Sword of Penitence, now lost), in 1927. He went on to make a further fifty-three films: twenty-six in his first five years as a director, and all but three for Shochiku. Ozu first made a number of short comedies, before turning to more serious themes in the 1930s. His Umarete wa mita keredo (I Was Born, But..., 1932), a comedy with serious overtones on adolescence, not only marks the beginning of this transition, but was also received by movie critics as the first notable work of social criticism in Japanese cinema, winning Ozu wide acclaim.

In 1935 Ozu made a short documentary with soundtrack: Kagami Shishi, in which Kokiguro VI performed Kabuki dance of the same title. This was made as per a request by the Ministry of Education.[3] Like the rest of Japan's cinema industry, Ozu was slow to switch to the production of talkies: his first film with a dialogue sound-track was Hitori Musuko (The Only Son) in 1936, five years after Japan's first talking film, Heinosuke Gosho's The Neighbor's Wife and Mine.

In July 1937, at a time when Shochiku was unhappy about Ozu's lack of box-office success (despite the praise and awards he received from critics), the thirty-four-year-old Ozu was conscripted into the Imperial Japanese Army, and he served for two years in China as an infantry corporal in the Second Chinese-Japanese War. The first film Ozu made on his return was the critically and commercially successful Toda-ke no Kyodai (Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family, 1941). He followed this with an autobiographical theme: Chichi Ariki (There Was a Father, 1942), describing the strong bonds of affection between a father and son despite years of separation. In 1943, Ozu was again drafted into the army to make a propaganda film in Burma. However, he was sent to Singapore instead.

Ozu's films were most favorably received from the late 1940s, with works such as Banshun (Late Spring, 1949), Tokyo Monogatari (Tokyo Story, 1953)—considered to be his masterpiece—Ochazuke no Aji (The Flavour of Green Tea Over Rice, 1952), Soshun (Early Spring, 1956), Higanbana (Equinox Flower, 1958, his first film in colour), Ukigusa (Floating Weeds, 1959) and Akibiyori (Late Autumn, 1960). Ozu often worked with screenwriter Kogo Noda; other regular collaborators included camera man Yuharu Atsuta and the actors Chishu Ryu, Setsuko Hara, and Haruko Sugimura.

As a director, Ozu was eccentric and a notorious perfectionist. His films were typically infused with the concept of mono no aware, an awareness of the impermanence of things. He was seen as one of the "most Japanese" of film makers, and his work was only rarely shown overseas before the 1960s. Ozu's last film was Sanma no aji (An Autumn Afternoon) in 1962.

He once served as president of the Directors Guild of Japan.[4]

Legacy and style

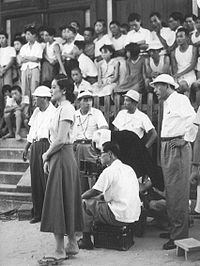

Yasujiro Ozu (far right) on location of Tokyo Story (1953).

Yasujiro Ozu (far right) on location of Tokyo Story (1953).

Ozu is probably as well known for the technical style and innovation of his films as for the narrative content. The style of his films is most distinctive in his later films, a style he had not fully developed until his post-war talkies. He did not conform to most Hollywood conventions, most notably the 180 degree rule. Also, rather than using the typical over-the-shoulder shots in his dialogue scenes, the camera gazes on the actors directly, which has the effect of placing the viewer in the middle of the scene. Ozu did not use typical transitions between scenes, either. In between scenes he would show shots of certain static objects as transitions, or use direct cuts, rather than fades or dissolves. Most often the static objects would be buildings, where the next indoor scene would take place. It was during these transitions that he would use music, which might begin at the end of one scene, progress through the static transition, and fade into the new scene. He rarely used non-diegetic music in any scenes other than in the transitions. Ozu moved the camera less and less as his career progressed, and ceased using tracking shots altogether in his color films.

He invented the "tatami shot", in which the camera is placed at a low height, supposedly at the eye level of a person kneeling on a tatami mat. Actually, Ozu's camera is often even lower than that, only one or two feet off the ground. He used this low height even when there were no sitting scenes, such as when his characters walked down hallways.

Ozu also eschewed the traditional rules of filmic storytelling, most notably eyelines. In his review of Floating Weeds, film critic Roger Ebert recounts

[Ozu] once had a young assistant who suggested that perhaps he should shoot conversations so that it seemed to the audience that the characters were looking at one another. Ozu agreed to a test. They shot a scene both ways, and compared them. "You see?" Ozu said. "No difference!"[5]

In narrative structure, Ozu was also an innovator in his use of ellipses, in which many major events are left out, leaving only the space between them. For example, in An Autumn Afternoon a wedding is mentioned in one scene, and then in the next, a reference is made to the wedding that has already occurred. The wedding, however, never occurs on screen. This is typical of Ozu's films. Usually Ozu elides moments that Hollywood films use to stir an emotional reaction from the audience, thus eschewing melodrama.

Ozu's films also featured more varied female roles. Most notably in the Noriko trilogy (Late Spring, Early Summer, and Tokyo Story), his female characters exhibited an independence and assertiveness that was a departure from more traditional Japanese views of women.

Ozu's work anticipated some techniques used by later art-film directors: infrequent use of non-diegetic music, a distinctive visual style, minimalist storytelling, and a character-driven emphasis on quiet and intelligent conversation.

Ozu's influence on the modern art film has been tremendous. Jim Jarmusch, Wim Wenders, Mike Leigh, Deepa Mehta, Aki Kaurismaki and Pedro Costa have all admitted to having been profoundly influenced by his films. Paul Schrader had a high opinion of him as well, and in his book Transcendental Styles in Film relates Ozu to Robert Bresson and Carl Theodor Dreyer.

Ozu had some famous detractors. Japanese "New-Wave" filmmakers Shohei Imamura and Nagisa Oshima were completely uninterested in Ozu's style of film making. Akira Kurosawa's more gentle criticism was that Ozu's work was too rarefied; he wrote in his autobiography that he disliked their "dignified severity".

Tributes and documentaries

- The 2003 movie Five Dedicated to Ozu, by Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami, is a tribute to Ozu. The film consists of five long takes, averaging about 16 minutes each.

- In the Wim Wenders documentary film Tokyo-Ga, the director travels to Japan to explore the world of Ozu, interviewing both Chishu Ryu and Yuharu Atsuta.

- In 2003, the centenary of Ozu's birth was commemorated at various film festivals around the world. Shochiku produced the film Café Lumière (珈琲時光), directed by Taiwanese filmmaker Hou Hsiao-Hsien as homage to Ozu, with direct reference to the late master's Tokyo Story (1953), to premiere on Ozu's birthday.

- John Walker, former editor of Halliwell`s Film Guide, placed Tokyo Story top in a list of the best 1000 films yet made.

Filmography

Filmography of Yasujirō Ozu[6][7] Year Japanese Title Rōmaji English Title Notes Silent films 1927 懺悔の刃 Zange no yaiba Sword of Penitence Lost 1928 若人の夢 Wakodo no yume Dreams of Youth Lost 女房紛失 Nyobo funshitsu Wife Lost Lost カボチャ Kabocha Pumpkin Lost 引越し夫婦 Hikkoshi fufu A Couple on the Move Lost 肉体美 Nikutaibi Body Beautiful Lost 1929 宝の山 Takara no yama Treasure Mountain Lost 学生ロマンス 若き日 Wakaki hi Days of Youth Ozu's earliest surviving film 和製喧嘩友達 Wasei kenka tomodachi Fighting Friends Japanese Style 14 minutes survive 大学は出たけれど Daigaku wa detakeredo I Graduated, But... 10 minutes survive 会社員生活 Kaishain seikatsu The Life of an Office Worker Lost 突貫小僧 Tokkan kozo A Straightforward Boy Short film 1930 結婚学入門 Kekkongaku nyumon An Introduction to Marriage Lost 朗かに歩め Hogaraka ni ayume Walk Cheerfully 落第はしたけれど Rakudai wa shitakeredo I Flunked, But... その夜の妻 Sono yo no tsuma That Night's Wife エロ神の怨霊 Erogami no onryo The Revengeful Spirit of Eros Lost 足に触った幸運 Ashi ni sawatta koun The Luck Which Touched the Leg Lost お嬢さん Ojosan Young Miss Lost 1931 淑女と髭 Shukujo to hige The Lady and the Beard 美人と哀愁 Bijin aishu Beauty's Sorrows Lost 東京の合唱 Tokyo no kôrasu Tokyo Chorus 1932 春は御婦人から Harn wa gofujin kara Spring Comes from the Ladies Lost 大人の見る繪本 生れてはみたけれど Umarete wa mita keredo I Was Born, But... 靑春の夢いまいづこ Seishun no yume imaizuko Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth? また逢ふ日まで Mata au hi made Until the Day We Meet Again Lost 1933 東京の女 Tokyo no onna Woman of Tokyo 非常線の女 Hijosen no onna Dragnet Girl 出来ごころ Degigokoro Passing Fancy 1934 母を恋はずや Haha o kowazuya A Mother Should Be Loved 浮草物語 Ukigusa monogatari A Story of Floating Weeds 1935 箱入娘 Hakoiri musume An Innocent Maid Lost 菊五郎の鏡獅子 Kagamijishi Kagamijishi Documentary 東京の宿 Tokyo no yado An Inn in Tokyo 1936 大学よいとこ Daigaku yoitoko College is a Nice Place Lost Sound, black-and-white films 1936 ひとり息子 Hitori musuko The Only Son Ozu's first sound film 1937 淑女は何を忘れたか Shukujo wa nani o wasuretaka What Did the Lady Forget? 1941 戸田家の兄妹 Todake no kyodai Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family 1942 父ありき Chichi ariki There Was a Father 1947 長屋紳士録 Nagaya Shinshiroku Record of a Tenement Gentleman 1948 風の中の牝鶏 Kaze no naka no mendori A Hen in the Wind 1949 晩春 Banshun Late Spring Ozu's first film with Setsuko Hara 1950 宗方姉妹 Munekata kyōdai The Munekata Sisters 1951 麥秋 Bakushu Early Summer 1952 お茶漬けの味 Ochazuke no aji The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice Adapted from rejected 1939 script 1953 東京物語 Tokyo monogatari Tokyo Story 1956 早春 Soshun Early Spring 1957 東京暮色 Tōkyō boshoku Tokyo Twilight Colour films 1958 彼岸花 Higanbana Equinox Flower Ozu's first film in colour 1959 お早よう Ohayo Good Morning Remake of I Was Born, But... 浮草 Ukigusa Floating Weeds Remake of A Story of Floating Weeds 1960 秋日和 Akibiyori Late Autumn 1961 小早川家の秋 Kohayagawa-ke no aki The End of Summer 1962 秋刀魚の味 Sanma no aji An Autumn Afternoon Ozu's final work Notes

- ^ Mark Weston Giants of Japan, Kodansha International, 1999, p. 303

- ^ "Yasujiro Ozu's gravesite in Kita-Kamakura: How to get there (Part Two).". http://www.easterwood.org/ozu/gravesite/directions2.html. Retrieved 2009-08-20. The simple inscription is referred to in the Wim Wenders film Tokyo-Ga when Wenders visits Ozu's grave with the actor Chishu Ryu.

- ^ Google Book Result from Donald Richie's book

- ^ "Nihon eiga kantoku kyōkai nenpyō" (in Japanese). Nihon eiga kantoku kyōkai. http://www.dgj.or.jp/about_g/chronology.html. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ Roger Ebert’s Great Movies review of Floating Weeds

- ^ Hasumi 1998, p. 229

- ^ Sato 1997b, p. 280

References

- Ozu by Donald Richie. University of California Press; (July 1977), ISBN 0-520-03277-2

- Yasujiro Ozu in Japanese Film Directors by Audie Bock. Kodansha International Ltd; (1978), ISBN 0-870-11304-6

- Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema by David Bordwell. Princeton University Press; (1988), ISBN 0-691-00822-1

- Ozu's Anti-Cinema by Kiju Yoshida. Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan; (1998), ISBN 1-929280-27-0

- Ozu Yasujiro zenshū (Ozu Yasujiro's Complete Works—two volume set of Ozu's scripts). Shinshokan; (March 2003), ISBN 4-403-15001-2 (in Japanese)

- Ozu Yasujiro no nazo (The Riddle of Ozu Yasujiro—manga biography of Ozu). Shōgakukan; (March 2001), ISBN 4-09-179321-5 (in Japanese)

- Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer by Paul Schrader (1972) ISBN 0-306-80335-6

- Hasumi, Shiguehiko (1998), Yasujirô Ozu, Paris: Cahiers du cinéma, ISBN 2-86642-191-4

- Sato, Tadao (1997b), Le Cinéma japonais - Tome II, Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, ISBN 2-85850-930-1

- Torres Hortelano, Lorenzo J., Primavera tardía de Yasujiro Ozu : cine clásico y poética zen , Caja España (León), Obra Social y Cultural, ISBN 978-84-95917-24-9

External links

- Yasujiro Ozu at the Internet Movie Database

- Early Summer Review at subtitledonline.com

- Digital Ozu

- Profile at Japan Zone

- Directions for finding Yasujiro Ozu's grave at Engaku-ji

- "The quiet master" at The Guardian

- Yasujiro Ozu (Japanese) at the Japanese Movie Database

- Ozu's Angry Women by Shigehiko Hasumi

- Ozu Yasujirō: Simply too Japanese

- Yasujirō Ozu at Find a Grave

- Ozu-san.com - A Website Dedicated to Ozu Yasujiro

- "Notes on Ozu's Cinematic Style," William Rothman in the Stanley Cavell special issue (Jeffrey Crouse, editor), Film International Issue 22, Vol, 4, No, 4, 2006.

Films directed by Yasujirō Ozu Days of Youth (1929) · Walk Cheerfully (1930) · I Flunked, But... (1930) · That Night's Wife (1930) · The Lady and The Beard (1931) · Tokyo Chorus (1931) · I Was Born, But... (1932) · Where Now Are The Dreams Of Youth? (1932) · Woman of Tokyo (1933) · Dragnet Girl (1933) · Passing Fancy (1933) · A Mother Should be Loved (1934) · A Story of Floating Weeds (1934) · An Inn in Tokyo (1935) · The Only Son (1936) · What Did the Lady Forget? (1937) · Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family (1941) · There Was a Father (1942) · The Record of a Tenement Gentleman (1947) · A Hen in the Wind (1948) · Late Spring (1949) · The Munakata Sisters (1950) · Early Summer (1951) · The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice (1952) · Tokyo Story (1953) · Early Spring (1956) · Tokyo Twilight (1957) · Equinox Flower (1958) · Good Morning (1959) · Floating Weeds (1959) · Late Autumn (1960) · The End of Summer (1961) · An Autumn Afternoon (1962)

Categories:- Cancer deaths in Japan

- Japanese film directors

- People from Tokyo

- 1903 births

- 1963 deaths

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.