- Domestic partnership in California

-

Legal recognition of

same-sex relationshipsMarriage Performed in some jurisdictions Mexico: Mexico City

United States: CT, DC, IA, MA, NH, NY, VT, Coquille, SuquamishRecognized, not performed Aruba (Netherlands only)

Curaçao (Netherlands only)

Israel

Mexico: all states (Mexico City only)

Sint Maarten (Netherlands only)

United States: CA (conditional), MDCivil unions and

registered partnershipsPerformed in some jurisdictions Australia: ACT, NSW, TAS, VIC

Mexico: COA

United States: CA, CO, DE, HI, IL, ME, NJ, NV, OR, RI, WA, WIUnregistered cohabitation Recognized in some jurisdictions See also Same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage legislation

Timeline of same-sex marriage

Recognition of same-sex unions in Europe

Marriage privatization

Civil union

Domestic partnership

Listings by countryLGBT portal A California domestic partnership is a legal relationship available to same-sex couples, and to certain opposite-sex couples in which at least one party is at least 62 years of age. It affords the couple most but not all of "the same rights, protections, and benefits, and shall be subject to the same responsibilities, obligations, and duties under law..." as married spouses.[1][2]

Enacted in 1999, the domestic partnership registry was the first of its kind in the United States created by a legislature without court intervention. Initially, domestic partnerships enjoyed very few privileges—principally just hospital-visitation rights and the right to be claimed as a next of kin of the estate of a deceased partner. The legislature has since expanded the scope of California domestic partnerships, though these still do not provide all of the rights and responsibilities common to marriage. As such, it is now difficult to distinguish California domestic partnerships from civil unions offered in a handful of other states.

Although the program enjoys broad support in California,[3] it has been the source of some controversy. Groups opposed to the recognition of same-sex families have challenged the expansion of domestic partnerships in court. Conversely, advocates of same-sex marriage contend that anything less than full marriage rights extended to same-sex partners is analogous to the "separate but equal" racial laws of the Jim Crow era.

Contents

- 1 Specifics

- 2 Legislative history

- 3 Popular opinion

- 4 Challenges to domestic partnerships

- 5 Internal Revenue Service Ruling

- 6 References

- 7 External links

Specifics

California has expanded the scope or modified some of the processes in domestic partnerships in every legislative session since the legislature first created the registry. Consult the California Secretary of State for the most current information.[4]

Scope

As of 2007, California affords domestic partnerships most of the same rights and responsibilities as marriages under state law (Cal. Fam. Code §297.5). Among these:

- Making health care decisions for each other in certain circumstances

- Hospital and jail visitation rights that were previously reserved for family members related by blood, adoption or marriage to the sick, injured or incarcerated person.

- Access to family health insurance plans (Cal. Ins. Code §10121.7)

- Spousal insurance policies (auto, life, homeowners etc..), this applies to all forms of insurance through the California Insurance Equality Act (Cal. Ins. Code §381.5)

- Sick care and similar family leave

- Stepparent adoption procedures

- Presumption that both members of the partnership are the parents of a child born into the partnership

- Suing for wrongful death of a domestic partner

- Rights involving wills, intestate succession, conservatorships and trusts

- The same property tax provisions otherwise available only to married couples (Cal. R&T Code §62p)

- Access to some survivor pension benefits

- Supervision of the Superior Court of California over dissolution and nullity proceedings

- The obligation to file state tax returns as a married couple (260k) commencing with the 2007 tax year (Cal R&T Code §18521d)

- The right for either partner to take the other partner's surname after registration

- Community property rights and responsibilities previously only available to married spouses

- The right to request partner support (alimony) upon dissolution of the partnership (divorce)

- The same parental rights and responsibilities granted to and imposed upon spouses in a marriage

- The right to claim inheritance rights as a putative partner (equivalent to the rights given to heterosexual couples under the putative spouse doctrine) when one partner believes himself or herself to have entered into a domestic partnership in good faith and is given legal rights as a result of his or her reliance upon this belief.[5]

Differences from marriage

While domestic partners receive most of the benefits of marriage, several differences will remain until January 1, 2012. These differences include, in part:

- Couples seeking domestic partnership must have a common residence; this is not a requirement for marriage license applicants.[2]

- Couples seeking domestic partnership must be 18 or older; minors can be married before the age of 18 with the consent of their parents.[2]

- California permits married couples the option of confidential marriage; there is no equivalent institution for domestic partnerships. In confidential marriages, no witnesses are required and the marriage license is not a matter of public record.[2]

- Married partners of state employees are eligible for the CalPERS long-term care insurance plan; domestic partners are not.[2][6][7] In April 2010, a lawsuit was filed challenging the exclusion of same-sex couples from the program.[8]

In addition to these differences specific to the United States, some countries that recognize same-sex marriages performed in California as valid in their own country, (e.g., Israel [9]), do not recognize same-sex domestic partnerships performed in California.

Many supporters of same-sex marriage also argue that the use of the word marriage itself constitutes a significant social difference,[citation needed] and in the majority opinion of In Re Marriage Cases, the California Supreme Court agreed,[10] suggesting an analogy with a hypothetical that branded interracial marriages "transracial unions".[11]

A 2010 UCLA study published in the journal Health Affairs suggests various inequities (including "Inequities in marriage laws") might have "implications for who bears the burden of health care costs." That study finds that men in same-sex domestic partnerships in California only 42% as likely to receive dependent coverage for their partners as their married peers, and that women in same-sex domestic partnerships in California are only 28% as likely to receive that coverage.[12][13]

Eligibility

A couple that wishes to register must meet the following requirements:[14]

- Both persons have a common residence.

- Neither person is married to someone else or is a member of another domestic partnership with someone else that has not been terminated, dissolved, or adjudged a nullity.

- The two persons are not related by blood in a way that would prevent them from being married to each other in California.

- Both persons are at least 18 years of age.

- Either of the following:

- Both persons are members of the same sex.

- The partners are of the opposite sex, one or both of whom is above the age of 62, and one or both of whom meet specified eligibility requirements under the Social Security Act.

- Both persons are capable of consenting to the domestic partnership.

On October 9, 2011, Governor Jerry Brown signed a law that will completely harmonize domestic partnership eligibility requirements with those of marriage, effective January 1, 2012.[15]

Recognition of Out-of-State Same-Sex Unions

- A substantially similar legal union lawfully contracted in another state will be recognized as a domestic partnership in California. For example, a civil union contracted in New Jersey would qualify as a domestic partnership in California.

- A substantially similar legal union lawfully contracted in a foreign jurisdiction will be recognized as a domestic partnership in California. For example, a civil partnership in the United Kingdom or a civil union in Switzerland would qualify as a domestic partnership in California.

- A substantially weaker legal union contracted in another state or foreign jurisdiction may not qualify as a domestic partnership in California. A domestic partnership in Maine would, in all likelihood, fail to qualify as a domestic partnership in California.

- Same-sex marriages are not recognized as domestic partnerships in California.

- A same-sex marriage lawfully performed in another state or foreign jurisdiction on or before November 4, 2008 will be fully recognized and legally designated as marriage in California. This also applies to all lawful out-of-state and foreign same-sex marriages performed before California began granting marriage licenses to same-sex couples on June 17, 2008.

- A same-sex marriage lawfully performed in another state or foreign jurisdiction on or after November 5, 2008 will be fully recognized in California, but Proposition 8 precludes California from designating these relationships with the word "marriage." Unlike current domestic partners, these couples are afforded every single one of the legal rights, benefits, and obligations of marriage.[16]

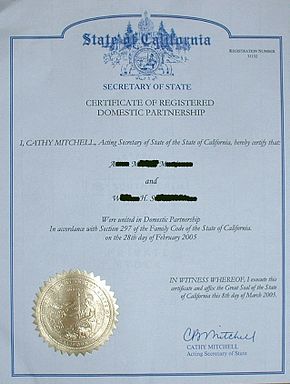

Registration

Domestic partner registration is an uncomplicated process, more simple and less costly than entering into a marriage. Both parties must sign a declaration listing their names and address.[17] Both signatures must be notarized. The declaration must then be transmitted to the Secretary of State along with a $10 filing fee (plus an additional $23 fee for same-sex couples to help fund LGBT-specific domestic violence training and services).[18] In this regard it is not like a marriage or civil union. Those unions require a ceremony, solemnized by either religious clergy or civil officials, to be deemed valid.[19]

Dissolution

In most cases, a domestic partnership must be dissolved through filing a court action identical[citation needed] to an action for dissolution of marriage. In limited circumstances, however, a filing with the Secretary of State may suffice. This procedure is available when the domestic partnership has not been in force for more than five years. The couple must also meet many other requirements that the dissolution be both simple and uncontested: no children (or current pregnancy) within the relationship, no real estate (including certain leases), and little joint property or debt. The parties must also review materials prepared by the Secretary of State, execute an agreement dividing assets and liability, and waive claims to domestic partner support. Where all the requirements are met, the partnership will terminate six months after the filing, unless either party revokes consent.

Legislative history

Attempts at the Municipal Level

In 1982, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed a measure to extend health insurance coverage to domestic partners of public employees (This was due in large part to the early days of the AIDS pandemic.), but did not provide for a registry available to the general public. Mayor Dianne Feinstein vetoed the measure.[20] Eventually San Francisco enacted a similar measure, as did other communities, such as Berkeley, and some local agencies.

In 1984, the City of Berkeley was the first city to pass a domestic partner policy for city and school district employees. This followed a year of work by the Domestic Partner Task Force chaired by Leland Traiman. Working with the Task Force was Tom Brougham, a Berkeley city employee who coined the term "domestic partner" and created the concept. All other domestic partner policies are patterned after Berkeley's.

In 1985, West Hollywood became the first U.S. city to enact a domestic partnership registry open to the citizenry. Eventually other cities, including San Francisco, Berkeley, and Santa Cruz, followed suit.[21]

Despite successes in a handful of localities, supporters of legal recognition same-sex couples could not overcome the limited geographical scope and relatively modest range of programs administered at the county and city level. In the 1990s, they turned their attention the state legislature.

Early attempts in the state legislature

Mirroring the experience of California’s local efforts, the state legislature did not initially succeed in providing health insurance coverage for domestic partners or creating a domestic partner registry for the general public.

- Assembly Bill 627 of 1995: In 1995, Assemblymember Richard Katz introduced a bill to create a domestic partner registry, open to both same- and opposite-sex couples. It sought to provide limited rights in medical decision making, conservatorships and a few related matters. It died in committee.[22]

- Murray-Katz Domestic Partnership Act of 1997: At the beginning of the 1997–1998 legislative session Assemblymember Kevin Murray introduced Assembly Bill 54. It was similar to Assembly Bill 627 of 1995. After successfully negotiating two Assembly committees, Murray did not bring the bill to a vote on the Assembly floor.[23]

- Assembly Bill 1059 of 1997: In 1997, Assemblymember Carole Migden introduced a bill that would require health insurance companies to offer for sale policies that would cover domestic partners of the insured, but did not require employers to provide the coverage. As later amended, it required employers who cover employees’ dependents to cover their domestic partners as well. The amended bill eventually gained approval of the legislature, but Governor Pete Wilson vetoed the measure.[24]

- Domestic Partnership Act of 1999: Kevin Murray, now a state senator, introduced Senate Bill 75 in December 1998. It was largely identical to his Assembly Bill 54 of 1997 and ultimately passed both houses of the state legislature. Governor Gray Davis vetoed the bill in favor of Assembly Bill 26, which was narrower in scope.[25]

Establishment and incremental expansion

Assembly Bill 26 of 1999

Simultaneously with the Domestic Partnership Act of 1999, Assemblymember Carole Migden introduced Assembly Bill 26 of 1999. As originally drafted, it covered all adult couples, like its unsuccessful senate counterpart. Before bringing the bill to the Assembly floor, however, Migden narrowed its scope. Based on objections from Governor Gray Davis, who did not want a competing alternative to marriage for opposite-sex couples, Migden eliminated coverage for opposite-sex couples where either participant was less than 62 years of age. The bill passed, and Davis signed into law on September 22, 1999. It provided for a public registry, hospital visitation rights, and authorized health insurance coverage for domestic partners of public employees.[26] While modest in scope, Assembly Bill 26 marked the first time a state legislature created a domestic partnership statute without the intervention of the courts. (Hawaii’s legislature enacted a more expansive reciprocal beneficiaries scheme in 1997 in response to an unfavorable lower court ruling; Vermont enacted a sweeping civil union bill in 2000 at the direction of its state Supreme Court.)

Assembly Bill 25 of 2001

In the first successful expansion of the domestic partnership act, Assemblymembers Carole Migden and Robert Hertzberg, joined by state Senator Sheila Kuehl, introduced a bill that added 18 new rights to the domestic partnership scheme. It also relaxed the requirements for opposite-sex couples, requiring only one of the participants to be over 62 years of age. The expanded rights included standing to sue (for emotional distress or wrongful death), stepparent adoption, a variety of conservatorship rights, the right to make health care decisions for an incapacitated partner, certain rights regarding distribution of a deceased partner’s estate, limited taxpayer rights, sick leave to care for partners, and unemployment and disability insurance benefits. Governor Gray Davis signed the bill into law on October 22, 2001.[27]

Other bills in the 2001–2002 legislative session

During the 2001–2002 session, California enacted five more bills making minor changes:

- Senate Bill 1049 (Speier) permitted San Mateo County to provide survivor benefits to domestic partners.[28]

- Assembly Bill 2216 (Keeley) provided for intestate succession.[29]

- Assembly Bill 2777 (Nation) authorized Los Angeles, Santa Barbara and Marin counties to provide survivor benefits to domestic partners.[30]

- Senate Bill 1575 (Sher) exempts domestic partners from certain provisions voiding wills that they helped draft.[31]

- Senate Bill 1661 (Kuehl) extends temporary disability benefits to workers to take time off to care for a family member.[32]

Wholesale expansion

The introduction of The California Domestic Partner Rights and Responsibilities Act of 2003 (or Assembly Bill 205 of 2003) marked a major shift in the legislature’s approach to domestic partnerships. Earlier efforts afforded domestic partners only certain enumerated rights, which the legislature expanded in piecemeal fashion. This bill, introduced by Assemblymembers Jackie Goldberg, Christine Kehoe, Paul Koretz, John Laird, and Mark Leno, created the presumption that domestic partners were to have all of the rights and responsibilities afforded spouses under state law. The bill did carve out certain exceptions to this premise, principally involving the creation and dissolution of domestic partnerships and certain tax issues. It also, for the first time, recognized similar relationships, such as civil unions, created in other states. Because the legislation dramatically changed the circumstances of existing domestic partnerships, the legislature directed the Secretary of State to inform all previously registered domestic partnerships of the changes and delayed the effect of the law for an additional year, until January 1, 2005. Governor Gray Davis signed the bill into law on September 19, 2003.[33]

Subsequent changes and clarifications

Since enacting The California Domestic Partner Rights and Responsibilities Act of 2003, the legislature has passed several bills aimed at clarifying how certain spousal provisions should be treated in the context of domestic partnerships and made some modest changes. This subsequent legislation includes:

- Assembly Bill 2208 of 2004 (Kehoe) clarifies that health and disability-insurance providers must treat domestic partners the same as married spouses.[34]

- Senate Bill 565 of 2005 (Migden) allows transfer of property between domestic partners without reassessment for tax purposes.[35]

- Senate Bill 973 of 2005 (Kuehl) specifies that domestic partners of state workers are entitled to retroactive pension benefits, even if the worker entered retirement before the enactment of Assembly Bill 205.[36]

- Senate Bill 1827 of 2006 (Migden) requires domestic partners to file state income-tax returns under the same status as married couples (jointly or married filing separately), effective in the 2007 tax year.[37]

- Assembly Bill 2051 of 2006 (Cohn) creates programs and funding grants to reduce domestic violence in the LGBT community and increases the fee for registering a domestic partnership by $23 to fund these services. The new fees are effective January 1, 2007.[38]

- Assembly Bill 102 of 2007 (Ma) allows parties to a registered domestic partnership to legally change their name to include the last name of their partner.[39]

- Assembly Bill 2055 of 2010 (De La Torre) extends unemployment benefits to same-sex couples planning to enter into a domestic partnership if one of the partners loses his or her job.[40]

- Senate Bill 651 of 2011 (Leno) completely harmonizes domestic partnership eligibility requirements with those of marriage in addition to providing same-sex partners of public employees equal access to long-term care insurance coverage, effective January 1, 2012.[41]

- Senate Bill 757 of 2011 (Lieu) requires all insurance providers selling their products in California to provide the same coverage to domestic partners as they do to married couples, effective January 1, 2012.[42]

Popular opinion

California public opinion has long supported legal protections for gay and lesbian couples. In early 1997, two and half years before any statewide recognition occurred, polls showed two-thirds of Californians supported the limited provisions in unsuccessful bills debated in the legislature at the time. There was also strong support (59 percent) for broader provisions (pension, health, leave and survivor benefits) that weren’t enacted until more than four years later.[43]

Polls consistently show a marked contrast between support for domestic partnerships and same-sex marriage. In 1997, roughly 38 percent of Californians supported same-sex marriage. More recent polls show an increase in support for same-sex marriage, but few polls suggest that there is any more support for same-sex marriage than a statistical tie with opponents.[44] On November 4, 2008, Californians voted, 52.2% to 47.8%, to eliminate the right of same sex couples to marry.[45]

Challenges to domestic partnerships

Despite broad support, California’s domestic partnership program has engendered opposition.

Referendum

California law provides for referendums, petition drives that would place any legislative enactment on the ballot for review. Following the passage of The California Domestic Partner Rights and Responsibilities Act of 2003, state senator William “Pete” Knight (author of the successful Proposition 22 initiative) and Assemblymember Ray Haynes sought put the new legislation to a popular vote. The referendum failed to qualify for the ballot.[46]

Litigation

Opponents of legal recognition for same-sex couples filed two lawsuits in the Superior Court of California. In the first case, state senator William “Pete” Knight sued Governor Gray Davis (later substituting Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger) on the grounds that A.B. 205 impermissibly amended Proposition 22, which Knight authored. Randy Thomasson (an opponent of gay rights and head of the Campaign for California Families) filed a similar lawsuit, which challenged both A.B. 205 and the earlier domestic-partner expansion in A.B. 25. Both lawsuits, consolidated into a single action, failed at the trial and appellate courts. In the wake of those decisions, opponents of legal recognition for LGBT families launched at least two recall efforts against Judge Loren McMaster, who presided over the trial-court hearings. The recall efforts also failed.[47]

Along similar legal lines, defendants in a wrongful-death action brought by the survivor of a domestic partnership mounted a defense based partly on the ground that the legislative enactments giving a domestic partner standing to sue for wrongful death ran afoul of Proposition 22 (among other defenses). That defense failed on appeal.[48]

Main article: California Proposition 22 (2000)Proponents of same-sex marriage, including the City and County of San Francisco, have challenged the state’s opposite-sex marriage requirements on constitutional grounds. In pursuing these claims, the plaintiffs argue that even the broad protections of California’s domestic partnership scheme constitute a “separate but unequal” discriminatory framework. In May 2008, the Supreme Court of California ruled in their favor in In re Marriage Cases, overruling Proposition 22 and effectively legalizing same-sex marriage in California.

Main article: Same-sex marriage in CaliforniaConstitutional amendments

Immediately following the passage of The California Domestic Partner Rights and Responsibilities Act of 2003, a petition drive began to amend the California Constitution to forbid any recognition—including domestic partnerships—of LBGT relationships.[49] The measure failed to qualify for the ballot.

For a month in early 2004, San Francisco issued marriage licenses to same-sex couples. The Supreme Court of California halted that process and later declared the marriages void. Regardless, four separate groups began petition drives to amend the California Constitution to prevent same-sex marriage and repeal domestic-partnership rights.[50] The renewed efforts peaked in 2005,[51] but have continued since. These groups have filed a total of 20 petitions, but none of the proposed amendments has qualified for the ballot.[52]

In 2008, two of these groups moved[53] to qualify ballot initiatives to amend the California Constitution on the November 2008 ballot. One qualified as Proposition 8. The amendment eliminates the right of same-sex couples to marry, but does not repeal any rights granted to domestic partnerships and registration for domestic partnerships remains legal in California.[54] In late 2008, Proposition 8 was passed by the voters, in 2009, the legality of Proposition 8 was upheld by the California Supreme Court in Strauss v. Horton holding that same-sex couples have all the rights of heterosexual couples, except the right to the "designation" of marriage and that such a holding does not violate California's privacy, equal protection, or due process laws.[55] Proposition 8 then was challenged in federal court on August 4th, 2010 in the Perry v. Schwarzenegger trial, as it was found to have violated the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the 14th Amendment of the Federal Constitution.

Internal Revenue Service Ruling

In late May 2010, the Internal Revenue Service reversed a 2006 ruling, and declared domestic partners in California must be treated the same as heterosexual couples due to a change to the California community property tax law in 2007.[56] The IRS ruled the approximately 58,000 couples who are registered as domestic partners in California must combine their income for federal tax purposes, and then each report half of the total income on their separate tax returns. If one of the partners makes significantly more than the other, the net result is a lower tax obligation for the couple. This ruling may affect other community property states, such as Nevada and Washington.[57]

References

- ^ FAMILY.CODE SECTION 297-297.5[1]

- ^ a b c d e In Re Marriage Cases, California Supreme Court Decision, footnote 24, pages 42-44.

- ^ “California Opinion Index: A Digest on How the California Public Views Gay and Lesbian Rights Issues.” The Field Poll: San Francisco (March 2006).

- ^ Domestic Partners Registry - California Secretary of State

- ^ Ellis v. Arriaga, 162 CA4th 1000, 109 (2008) overturning Velez v. Smith (2006)

- ^ Congressional Testimony of Gregory Franklin, Assistant Executive Officer of CalPERS, to the Subcomittee on Federal Workforce, Postal Service and District of Columbia, July 8, 2009, p. 3. "Of note is that the CalPERS long-term care insurance program was exempt from AB 205 because the program is governed by the U.S. Internal Revenue Code as a tax-exempt governmental plan and the federal government does not recognized domestic partnerships. Allowing domestic partners to enroll in the long-term-care plan would in effect be enrolling persons who are not eligible under federal tax law and therefore threaten the tax-exempt status of the plan. "

- ^ California Family Code, Section 297.5 (g) establishes this exception.

- ^ Bob Egelko (April 14, 2010). "Same-sex couples sue over state insurance". San Francisco Chronicle. http://articles.sfgate.com/2010-04-14/bay-area/20848622_1_long-term-care-same-sex-partners-care-or-nursing-homes. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ^ Search - Global Edition - The New York Times

- ^ In Re Marriage Cases, California Supreme Court Decision, page 81.

- ^ "Gay Marriage Recognition Bill Signed In California". cbs13.com. 2009-10-29. http://cbs13.com/local/gay.marriage.recognition.2.1243603.html. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ^ Ponce, Ninez A.; Susan D. Cochran, Jennifer C. Pizer and Vickie M. Mays (2010). "The Effects Of Unequal Access To Health Insurance For Same-Sex Couples In California". Health Affairs 29 (8): 1539–1548. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0583. http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/abstract/hlthaff.2009.0583. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ^ "UCLA study finds health insurance inequities for same-sex couples". UCLA. June 25, 2010. http://newsroom.ucla.edu/portal/ucla/ucla-study-finds-health-insurance-160792.aspx. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ^ Frequently Asked Questions - Domestic Partners Registry - California Secretary of State

- ^ http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/11-12/bill/sen/sb_0651-0700/sb_651_bill_20111009_chaptered.html

- ^ http://www.eqca.org/atf/cf/%7B34f258b3-8482-4943-91cb-08c4b0246a88%7D/SB%2054%20FAQ.PDF

- ^ "Domestic Partners Registry". California Secretary of State. http://www.sos.ca.gov/dpregistry/. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ^ "Forms & Fees - Domestic Partners Registry". California Secretary of State. http://www.sos.ca.gov/dpregistry/forms.htm. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ^ "Marriage Info to Officiants Website". California Department of Public Health. http://www.cdph.ca.gov/certlic/birthdeathmar/Documents/Marriage%20Info%20to%20Officiants%20Website.doc. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ^ Bishop, Katherine. “San Francisco Grants Recognition to Couples Who Aren’t Married.” New York Times 31 May 1989.

- ^ Becker, Lewis. “Recognition of Domestic Partnerships by Governmental Entities and Private Employers.” National Journal of Sexual Orientation Law. 1.1 (1995): 91-92.

- ^ AB 627. Legislative Counsel of California. 1995–1996 Session.

- ^ AB 54. Legislative Counsel of California. 1997–1998 Session.

- ^ 1059. Legislative Counsel of California. 1997–1998 Session.

- ^ SB 75. Legislative Counsel of California. 1999–2000 Session.

- ^ AB 26. Legislative Counsel of California. 1999–2000 Session.

- ^ AB 25. Legislative Counsel of California. 2001–2002 Session.

- ^ SB 1049. Legislative Counsel of California. 2001–2002 Session.

- ^ AB 2216. Legislative Counsel of California. 2001–2002 Session.

- ^ AB 2777. Legislative Counsel of California. 2001–2002 Session.

- ^ SB 1575. Legislative Counsel of California. 2001–2002 Session.

- ^ SB 1661. Legislative Counsel of California. 2001–2002 Session.

- ^ AB 205. Legislative Counsel of California. 2003–2004 Session.

- ^ AB 2208. Legislative Counsel of California. 2003–2004 Session.

- ^ SB 565. Legislative Counsel of California. 2005–2006 Session.

- ^ SB 973. Legislative Counsel of California. 2005–2006 Session.

- ^ SB 1827. Legislative Counsel of California. 2005–2006 Session.

- ^ SB 2051. Legislative Counsel of California. 2005–2006 Session.

- ^ AB 102 Assembly Bill - CHAPTERED

- ^ AB 2055 (De La Torre): Unemployment insurance: benefits: eligibility: reserve accounts: domestic partners

- ^ http://www.eqca.org/site/pp.asp?c=kuLRJ9MRKrH&b=6585373

- ^ http://www.eqca.org/site/pp.asp?c=kuLRJ9MRKrH&b=6744981

- ^ DiCamillo, Mark and Mervin Field. “Statewide survey.” The Field Institute: San Francisco 1997.

- ^ Baldassare, Mark. “Californians & the Future.” Public Policy Institute of California: San Francisco. Sep. 2006.

- ^ California Secretary of State, Election Results "[2][dead link]".

- ^ “Initiative Update as of December 15, 2003.[dead link]” California Secretary of State; also, “Referendum on California's Historic Domestic Partner Law Fails to Qualify for Ballot.” Equality California: San Francisco 22 Dec. 2003.

- ^ Gardner, Michael. “Gay marriage opponents aim to recall judge.” San Diego Union Tribune 31 Dec. 2004.

- ^ Armijo v. Miles (2005) 127 Cal.App.4th 1405.

- ^ “Initiative Update as of October 2, 2003.”[dead link] California Secretary of State.

- ^ (Archived) Position statement: VoteYesMarriage.com; Position statement:[dead link] ProtectMarriage.com.

- ^ Buchanan, Wyatt. "The Battle Over Same Sex Marriage." San Francisco Chronicle 12 Aug 2005: B1.

- ^ Office of Attorney General. Initiative Measures, Inactive.

- ^ Initiative Update as of February 19, 2008. California Secretary of State.

- ^ Leff, Lisa (2008-02-15). "Same-sex Marriage Amendment Sought". Associated Press. http://www.insidebayarea.com/ci_8269885?source=rss.

- ^ http://www.courtinfo.ca.gov/opinions/archive/S168047.PDF -- For a review see: Thomas Kupka, Names and Designations in Law, in: The Journal Jurisprudence 6 (2010) 121-130.

- ^ Michael J. Montemurro (2010-05-05). "PLR-149319-09". Internal Revenue Service. http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-wd/1021048.pdf. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- ^ Meckler, Laura (2010-06-05), "Gay Couples Get Equal Tax Treatment", The Wall Street Journal, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704080104575286931017169308.html?mod=googlenews_wsj, retrieved 2010-06-06

External links

- Domestic Partners Registry. Information from the California Secretary of State. Includes downloadable forms.

- Name Changes. Information on how to change your name with the California Department of Motor Vehicles.

- 297-297.5 California Family Code. California Family Code on Domestic Partnerships.

- Fact sheet on the rights and responsibilities of California domestic partners by Equality California and the National Center for Lesbian Rights

- National Center for Lesbian Rights. Information about the legal rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people and their families, including a legal information hotline.

- California Franchise Tax Board Registered Domestic Partner Site

- California Franchise Tax Board Publication 737 Tax Information for Registered Domestic Partners (260k)

LGBT in California Community Gay villages · Community centersCulture San Francisco Pride · At The Beach LAHistory Rights and liberties Briggs Initiative · Consenting Adult Sex Bill · FAIR Education Act

Same-sex marriage and

Domestic partnershipDomestic Partner Task Force · California Proposition 22 (2000) · San Francisco 2004 same-sex weddings · In re Marriage Cases · California Proposition 8 (2008) (Post-election events, Protests, Other protests) · Strauss v. Horton · Perry v. SchwarzeneggerInstitutions Billy DeFrank LGBT Center · GLBT Historical Society · Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Center · ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives · San Diego LGBT Community Center · Lambda Archives of San Diego · San Francisco LGBT Community CenterSame-sex unions in the United States Main articles: State constitutional amendments banning (List by type) - Public opinion (Opponents - List of supporters) - Status by state (Law - Legislation) - Municipal domestic partnership registries Same-sex marriage legalized: Connecticut - District of Columbia - Iowa - Massachusetts - New Hampshire - New York - Vermont - Coquille, SuquamishSame-sex marriage recognized,

but not performed:California*# - MarylandCivil union or domestic partnership legal: California - Colorado - Delaware - District of Columbia - Hawaii - Illinois - Maine - Maryland - Nevada - New Jersey - Oregon - Rhode Island - Washington - WisconsinSame-sex marriage prohibited by statute: Delaware - Hawaii - Illinois - Indiana - Maine - Maryland - Minnesota - North Carolina - Pennsylvania - Puerto Rico - Washington - West Virginia - WyomingSame-sex marriage prohibited

by constitutional amendment:Alaska - Arizona - California# - Colorado - Mississippi - Missouri - Montana - Nevada - Oregon - TennesseeAll types of same-sex unions prohibited

by constitutional amendment:Recognition of same-sex unions undefined

by statute or constitutional amendment:American Samoa - Guam - New MexicoNotes:

*All out-of-state same-sex marriages are given the benefits of marriage under California law, although only those performed before November 5, 2008 are granted the designation "marriage".

# California's ban on same-sex marriage remains in limbo following a federal case finding the ban unconstitutional, which is stayed pending appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.Categories:- Family law

- California law

- Recognition of same-sex relationships in the United States

- LGBT rights in California

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.