- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

-

"NIAID" redirects here. For other uses, see NIAID (disambiguation).

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases NIAID

NIAID logo Agency overview Formed 1955 Preceding agency National Microbiological Institute Headquarters Bethesda, Maryland Agency executive Anthony S. Fauci, Director Parent agency National Institutes of Health Website niaid.nih.gov The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) is one of the 27 institutes and centers that make up the National Institutes of Health (NIH), an agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). NIAID’s mission is to conduct basic and applied research to better understand, treat, and ultimately prevent infectious, immunologic, and allergic diseases.[1]

NIAID has intramural, or in-house, laboratories in Maryland and Montana, and funds research conducted by scientists at institutions in the United States and throughout the world. NIAID also works closely with partners in academia, industry, government, and non-governmental organizations in multifaceted and multidisciplinary efforts to address emerging health challenges such as the pandemic H1N1/09 virus.

Contents

History[2]

NIAID traces its origins to a small laboratory established in 1887 at the Marine Hospital on Staten Island, New York (now the Bayley Seton Hospital). Officials of the Marine Hospital Service in New York decided to open a research laboratory to study the link between microscopic organisms and infectious diseases. Dr. Joseph J. Kinyoun, a medical officer with the Marine Hospital Service, was selected to create this laboratory which he called a “laboratory of hygiene”.[3]

Dr. Kinyoun's lab was renamed the Hygienic Laboratory in 1891 and moved to Washington, D.C., where Congress authorized it to investigate "infectious and contagious diseases and matters pertaining to the public health."[4] With the passage of the Ransdell Act in 1930, the Hygienic Laboratory became the National Institute of Health. In 1937, the Rocky Mountain Laboratory, then part of the United States Public Health Service, was transferred to Division of Infectious Diseases, part of the NIH.

In mid-1948, the National Institute of Health became the National Institutes of Health (NIH) with the creation of four new institutes.[5] On October 8, 1948, the Rocky Mountain Laboratory and the Biologics Control Laboratory were joined with the NIH Division of Infectious Diseases and Division of Tropical Diseases to form the National Microbiological Institute. In 1955, Congress changed the name of the National Microbiological Institute to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to reflect the inclusion of allergy and immunology research. That change became effective on December 29, 1955.[6]

Organizational structure

- Office of the Director

- Division of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (DAIDS)

- Division of Allergy, Immunology, and Transplantation (DAIT)

- Division of Clinical Research (DCR)

- Division of Extramural Activities (DEA)

- Division of Intramural Research (DIR)

- Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (DMID)

- Dale and Betty Bumpers Vaccine Research Center (VRC)

Research Priorities[7]

NIAID’s research priorities are focused on (1) expanding the breadth and depth of knowledge in all areas of infectious, immunologic, and allergic diseases, and (2) developing flexible domestic and international research capacities to respond appropriately to emerging and re-emerging disease threats wherever they may occur.

NIAID’s mission areas are:

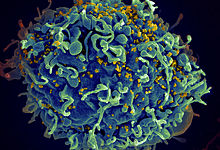

Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS)

The goals in this area are finding a cure for HIV-infected individuals; developing preventive strategies, including vaccines and treatment as prevention; developing therapeutic strategies for preventing and treating co-infections such as TB and hepatitis C in HIV-infected individuals; and addressing the long-term consequences of HIV treatment.

Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases (BioD)

The goals of this mission area are to better understand how these deliberately emerging (i.e. intentionally caused) and naturally emerging infectious agents cause disease and how the immune system responds to them.

Infectious and Immunologic Diseases (IID)

The goal of this mission area is to understand how aberrant responses of the immune system play a critical role in the development of immune-related disorders such as asthma, allergies, autoimmune diseases, and transplant rejection. This research helps improve the understanding of how the immune system functions when it is healthy or unhealthy and provides the basis for development of new diagnostic tools and interventions for immune-related diseases.

Achievements[8]

NIAID has established a reputation for being on the cutting edge of scientific progress both through its intramural labs and through the research it funds at academic institutions. For example, NIAID collaborations with various partners led to the development of FDA-approved vaccines for influenza (FluMist), hepatitis A (Havrix), and rotavirus (RotaShield). NIAID also was instrumental in the development and licensure of acellular pertussis vaccines, conjugate vaccines for Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b or Hib, and a preventive therapy for respiratory syncytial virus or RSV (Synagis). Additionally, NIAID partnerships with industry and academia have led to the advancement of diagnostic tests for several important infectious diseases, including malaria (ParaSight F), tuberculosis (GeneXpert MTB/RIF), and norovirus (Ridascreen Norovirus 3rd Generation EIA).

NIAID is a recognized pioneer in the study of HIV/AIDS and has helped improve standards of care of HIV-infected people in the United States and abroad. For example, its research on mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV has paved the way for new health interventions that have saved many lives. In 1994, a landmark study co-sponsored by NIAID demonstrated that the drug AZT, given to HIV-infected women who had little or no prior antiretroviral therapy (ART), reduced the risk of MTCT by two-thirds. This and other findings since then have helped reduce perinatal HIV infections in the United States by more than 90 percent, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 1999, an NIAID-funded study in Uganda found that two oral doses of the inexpensive drug nevirapine—one given to HIV-infected mothers at the onset of labor and another to their infants soon after birth—reduced MTCT by half when compared with a similar course of AZT. Subsequent clinical trials, including some funded by NIAID, showed that AIDS drugs also can reduce the risk of MTCT through breast milk. These and other studies have led to World Health Organization recommendations that can help prevent MTCT while allowing women in resource-limited settings to breastfeed their infants safely.

More recently, NIAID-funded scientists found that testing at-risk infants for HIV and then giving ART immediately to those who test positive dramatically reduces rates of illness and death. HIV-infected infants were four times less likely to die if given ART immediately after they were diagnosed with HIV, when compared with the standard of care (beginning ART in infants when they showed signs of HIV illness or a weakened immune system).

This finding helped influence the World Health Organization (WHO) to change its guidelines for treating HIV-infected infants. The guidelines now strongly recommend starting ART in all children under age 2 immediately after they have been diagnosed with HIV, regardless of their health status.

Footnotes

- ^ NIAID Fiscal Year 2009 Fact Book

- ^ NIAID History,

- ^ Luiggi, Cristina (2011-05-28). "One-Man NIH, 1887". The Scientist. http://the-scientist.com/2011/05/28/one-man-nih-1887/.

- ^ Mintzer

- ^ NIH Almanac

- ^ National Archives

- ^ NIAID Fiscal Year 2009 Fact Book

- ^ NIAID Showcase

References

Mintzer, Rich (2002). The National Institutes of Health. Chelsea House. ISBN 0-7910-6793-9

NIAID Fiscal Year 2009 Fact Book (2010). US Department of Health and Human Services.

External links

- NIAID home page

- NIAID Fiscal Year 2009 Fact Book

- Mintzer, Rich (2002). The National Institutes of Health

- NIAID Showcase

- NIAID Division of Intramural Research Showcase

- National Institutes of Health homepage

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services homepage

- One-Man NIH, 1887

- Anthony S. Fauci official biography

- Previous NIAID Directors

Categories:- National Institutes of Health

- United States government stubs

- Medical organization stubs

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.