- Gastroenteritis

-

Gastroenteritis Classification and external resources

Gastroenteritis viruses: A = rotavirus, B = adenovirus, C = Norovirus and D = Astrovirus. The virus particles are shown at the same magnification to allow size comparison.ICD-10 A02.0, A08, A09, J10.8, J11.8, K52 ICD-9 009.0, 009.1, 558 DiseasesDB 30726 eMedicine emerg/213 MeSH D005759 Gastroenteritis (also known as gastric flu, stomach flu, and stomach virus, although unrelated to influenza) is marked by severe inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract involving both the stomach and small intestine resulting in acute diarrhea and vomiting. It can be transferred by contact with contaminated food and water. The inflammation is caused most often[citation needed] by an infection from certain viruses or less often[citation needed] by bacteria, their toxins (e.g. SEB), parasites, or an adverse reaction to something in the diet or medication.

At least 50% of cases of gastroenteritis resulting from foodborne illness are caused by norovirus.[1] Another 20% of cases, and the majority of severe cases in children, are due to rotavirus. Other significant viral agents include adenovirus[2] and astrovirus.

Risk factors include consumption of improperly prepared foods or contaminated water and travel or residence in areas of poor sanitation. It is also common for river swimmers to become infected during times of rain as a result of contaminated runoff water.[3]

Contents

Symptoms and signs

Gastroenteritis often involves stomach pain or spasms, diarrhea and/or vomiting, with noninflammatory infection of the upper small bowel, or inflammatory infections of the colon.[4][5][6][7]

The condition is usually of acute onset, normally lasting 1–6 days, and is self-limiting.

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Dehydration

- Fever

- Abnormal flatulence

- Abdominal cramps

- Bloody stools (dysentery – suggesting infection by amoeba, Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella or some pathogenic strains of Escherichia coli[2])

- Heartburn

The main contributing factors include poor feeding in infants. Diarrhea is common, and may be followed by vomiting. Viral diarrhea usually causes frequent watery stools, whereas blood stained diarrhea may be indicative of bacterial colitis. In some cases, even when the stomach is empty, bile can be vomited up.

A child with mild or moderate dehydration may have a prolonged capillary refill, poor skin turgor and abnormal breathing.[8]

Cause

Bacterial

Different species of pathogenic bacteria can cause gastroenteritis, including Salmonella, Shigella, Staphylococcus,Campylobacter jejuni, Clostridium, Escherichia coli, Yersinia, Vibrio cholerae, and others. Some sources of the infection are improperly prepared food, reheated meat dishes, seafood, dairy, and bakery products. Each organism causes slightly different symptoms but all result in diarrhea. Colitis, inflammation of the large intestine, may also be present. Such pathogenic enteric bacteria are generally distinguished from the usually harmless bacteria of the normal gut flora, but the distinction is often not fully clear, and Escherichia, for example, can belong to either group.

Pseudomembranous colitis is an important cause of diarrhea in patients often recently treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Traveler's diarrhea is usually a type of bacterial gastroenteritis.

If gastroenteritis in a child is severe enough to require admission to a hospital, then it is important to distinguish between bacterial and viral infections. Bacteria like Shigella and Campylobacter, and parasites like Giardia can be treated with antibiotics.

Viral

Viruses causing gastroenteritis include rotavirus, norovirus, adenovirus and astrovirus. Viruses do not respond to antibiotics and infected children usually make a full recovery after a few days.[9] Children admitted to hospital with gastroenteritis routinely are tested for rotavirus A to gather surveillance data relevant to the epidemiological effects of rotavirus vaccination programs.[10][11] These children are routinely tested also for norovirus, which is extraordinarily infectious and requires special isolation procedures to avoid transmission to other patients. Other methods, electron microscopy and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, are used in research laboratories.[12][13]

Diagnosis

Gastroenteritis is diagnosed based on symptoms, a complete medical history and a physical examination. An accurate medical history may provide valuable information on the existence or inexistence of similar symptoms in other members of the patient's family or friends. The duration, frequency, and description of the patient's bowel movements and if they experience vomiting are also relevant and these question are usually asked by a physician during the examination. [14] As hypoglycemia may occur in 9% of children measuring serum glucose is recommended.[8]

No specific diagnostic tests are required in most patients with simple gastroenteritis. If symptoms including fever, bloody stool and diarrhea persist for two weeks or more, examination of stool for Clostridium difficile may be advisable along with cultures for bacteria including Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter and enterotoxic Escherichia coli. Microscopy for parasites, ova and cysts may also be helpful.[citation needed]

A complete medical history may be helpful in diagnosing gastroenteritis. A complete and accurate medical history of the patient includes information on travel history, exposure to poisons or other irritants, diet change, food preparation habits or storage and medications. Patients who travel may be exposed to E. Coli infections or parasite infections contacted from beverages or food. Swimming in contaminated water or drinking from suspicious fresh water such as mountain streams or wells may indicate infection from Giardia - an organism found in water that causes diarrhea.

Food poisoning must be considered in cases when the patient was exposed to undercooked or improperly stored food. Depending on the type of bacteria that is causing the condition, the reactions appear in 2 to 72 hours. Detecting the specific infectious agent is required in order to establish a proper diagnosis and an effective treatment plan.

The doctor may want to find whether the patient has been using broad-spectrum or multiple antibiotics in their recent past. If so, they could be the cause of an irritation of the gastrointestinal tract.

During the physical examination, the doctor will look for other possible causes of the infection. Conditions such as appendicitis, gallbladder disease, pancreatitis or diverticulitis may cause similar symptoms but a physical examination will reveal a specific tenderness in the abdomen which is not present in gastroenteritis.

Diagnosing gastroenteritis is mainly an exclusion procedure. Therefore in rare cases when the symptoms are not enough to diagnose gastroenteritis, several tests may be performed in order to rule out other gastrointestinal disorders. These include rectal examinations, complete blood count, electrolytes and kidney function tests. However, when the symptoms are conclusive, no tests apart from the stool tests are required to correctly diagnose gastroenteritis especially if the patient has traveled to at-risk areas.

Differential

Infectious gastroenteritis is caused by a wide variety of bacteria and viruses. It is important to consider infectious gastroenteritis as adiagnosis per exclusionem. A few loose stools and vomiting may be the result of systemic infection such as pneumonia,septicemia, urinary tract infection and meningitis. Surgical conditions such as appendicitis, intussusception and, rarely, Hirschsprung's disease should be in the differential. Endocrine disorders (e.g.thyrotoxicosis and Addison's disease) are disorders that can cause diarrhea. Also, pancreatic insufficiency, short bowel syndrome, Whipple's disease, coeliac disease, and laxative abuse should be excluded as possibilities.[5]

Prevention

Lifestyle

Good hand washing has been found to decrease the rates of gastroenteritis in both the developing and developed world by about 30%.[8] Alcohol based gels may also be effective.[8]

Avoidance of potentially contaminated food or drink may be useful as a preventative measure.[15]

Vaccination

Since 2000, the implementation of a rotavirus vaccine has decreased the number of cases of diarrhea due to rotavirus in the United States.[16] It may be given to infants aged 6 to 32 weeks.[17] The vaccines has side effects that are similar to the mild flu symptoms.

Different types of vaccinations are available for Salmonella typhi and Vibrio cholera and which may be administered to people who intend traveling in at-risk areas. However, the vaccines that are currently available are effective only on rotavirual gastroenteritis.

Management

Gastroenteritis is usually an acute and self-limited disease that does not require pharmacological therapy.[18] The objective of treatment is to replace lost fluids and electrolytes. Oral rehydration is the preferred method of replacing these losses in children with mild to moderate dehydration.[19] Metoclopramide and ondansetron however may be helpful in children.[20]

Rehydration

The primary treatment of gastroenteritis in both children and adults is rehydration, i.e., replenishment of water and electrolytes lost in the stools. This is preferably achieved by giving the person oral rehydration therapy (ORT) although intravenous delivery may be required if a decreased level of consciousness or an ileus is present.[21][22] Complex-carbohydrate-based oral rehydration therapy such as those made from wheat or rice may be superior to simple sugar-based ORS.[23] Sugary drinks such as soft drinks and fruit juice are not recommended for gastroenteritis in children under 5 years of age as they may make the diarrhea worse.[18] Plain water may be used if specific ORS are unavailable or not palatable.[18] Intravenous fluids are recommended if severe dehydration is present, there is a decreased level of consciousness, or there is hemodynamic compromise (typically low blood pressure or a fast heart rate).[8]

Diet

It is recommended that breastfed infants continue to be nursed on demand and that formula-fed infants should continue their usual formula immediately after rehydration with oral rehydration solutions. Lactose-free or lactose-reduced formulas usually are not necessary.[24] Children receiving semisolid or solid foods should continue to receive their usual diet during episodes of diarrhea. Foods high in simple sugars should be avoided because the osmotic load might worsen diarrhea; therefore substantial amounts of soft drinks, juice, and other high simple sugar foods should be avoided.[24] The practice of withholding food is not recommended and immediate normal feeding is encouraged.[25] The BRAT diet (bananas, rice, applesauce, toast and tea) is no longer recommended, as it contains insufficient nutrients and has no benefit over normal feeding.[26]

Medications

- Antiemetics

Antiemetic drugs may be helpful for vomiting in children. Ondansetron has some utility with a single dose associated with less need for intravenous fluids, fewer hospitalizations, and decreased vomiting.[27][28][20] Metoclopramide also might be helpful.[20] However there was an increased number of children who returned and were subsequently admitted in those treated with ondansetron.[29] The intravenous preparation of ondansetron may be given orally.[30]

- Antibiotics

Antibiotics are not usually used for gastroenteritis, although they are sometimes used if symptoms are severe (such as dysentery)[31] or a susceptible bacterial cause is isolated or suspected.[32] If antibiotics are decided on, a fluoroquinolone or macrolide is often used.[6] Pseudomembranous colitis, usually caused by antibiotics use, is managed by discontinuing the causative agent and treating with either metronidazole or vancomycin.[6][7]

- Antimotility agents

Antimotility drugs have a theoretical risk of causing complications; clinical experience, however, has shown this to be unlikely.[5][6] They are thus discouraged in people with bloody diarrhea or diarrhea complicated by a fever.[4] Loperamide, an opioid analogue, is commonly used for the symptomatic treatment of diarrhea.[6] Loperamide is not recommended in children as it may cross the immature blood brain barrier and cause toxicity. Bismuth subsalicylate (BSS), an insoluble complex of trivalent bismuth and salicylate, can be used in mild-moderate cases.[5][6]

- Antispasmotics

Butylscopolamine (Buscopan) is useful in treating crampy abdominal pain.[33]

Alternative medicine

- Probiotics

Some probiotics have been shown to be beneficial in preventing and treating various forms of gastroenteritis.[26] They reduce both the duration of illness and the frequency of stools.[34] Fermented milk products (such as yogurt) also reduce the duration of symptoms.[35]

- Zinc

The World Health Organization recommends that infants and children receive a dietary supplement of zinc for up to two weeks after onset of gastroenteritis.[36] A 2009 trial however did not find any benefit from supplementation.[37]

Complications

Dehydration is a common complication of diarrhea. It can be made worse with the withholding fluids or the administration of juice / soft drinks.[38]

Reactive arthritis also called Reiter's syndrome can follow infectious dysentery. Onset typically occurs one to three weeks following the infection and may present acutely or insidiously.

Epidemiology

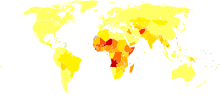

Disability-adjusted life year for diarrhea per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.

Disability-adjusted life year for diarrhea per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004. no data≤less 500500-10001000-15001500-20002000-25002500-30003000-35003500-40004000-45004500-50005000-6000≥6000

no data≤less 500500-10001000-15001500-20002000-25002500-30003000-35003500-40004000-45004500-50005000-6000≥6000Every year, worldwide, rotavirus in children under 5 causes 111 million cases of gastroenteritis and nearly half a million deaths. 82% of these deaths occur in the world's poorest nations.[39]

In 1980 gastroenteritis from all causes caused 4.6 million deaths in children with most of these occurring in the third world.[7] Lack of adequate safe water and sewage treatment has contributed to the spread of infectious gastroenteritis. Current death rates have come down significantly to approximately 1.5 million deaths annually in the year 2000, largely due to the global introduction of oral rehydration therapy.[40]

The incidence in the developed world is as high as 1-2.5 cases per child per year[citation needed] and is a major cause of hospitalization in this age group.

Age, living conditions, hygiene and cultural habits are important factors. Aetiological agents vary depending on the climate. Furthermore, most cases of gastroenteritis are seen during the winter in temperate climates and during summer in the tropics.[7]

History

Before the 20th century, the term "gastroenteritis" was not commonly used. What would now be diagnosed as gastroenteritis may have instead been diagnosed more specifically as typhoid fever or "cholera morbus", among others, or less specifically as "griping of the guts", "surfeit", "flux", "colic", "bowel complaint", or any one of a number of other archaic names for acute diarrhea.[41] Historians, genealogists, and other researchers should keep in mind that gastroenteritis was not considered a discrete diagnosis until fairly recently.

U.S. President Zachary Taylor died of "cholera morbus", equivalent to a diagnosis of gastroenteritis, on July 9, 1850.[42]

References

- ^ "Norovirus: Technical Fact Sheet". National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/revb/gastro/norovirus-factsheet.htm.

- ^ a b Murray PR, Pfaller MA, Rosenthal KS. Medical Microbiology. Mosby, 2005. ISBN 0-323-03303-2.

- ^ Seven Surfing Sicknesses.

- ^ a b Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine 16th Edition, The McGraw-Hill Companies, ISBN 0-07-140235-7

- ^ a b c d The Oxford Textbook of Medicine. Edited by David A. Warrell, Timothy M. Cox and John D. Firth with Edward J. Benz, Fourth Edition (2003), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-262922-0

- ^ a b c d e f Sleisenger & Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease 7th edition, by Mark Feldman; Lawrence S. Friedman; and Marvin H. Sleisenger, ISBN 0-7216-8973-6, Hardback, Saunders, Published July 2002

- ^ a b c d Mandell's Principles and Practices of Infection Diseases 6th Edition (2004) by Gerald L. Mandell MD, MACP, John E. Bennett MD, Raphael Dolin MD, ISBN 0-443-06643-4 · Hardback · 4016 Pages Churchill Livingstone

- ^ a b c d e Tintinalli, Judith E. (2010). Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (Emergency Medicine (Tintinalli)). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. pp. 830-839. ISBN 0-07-148480-9.

- ^ Haffejee IE (1991). "The pathophysiology, clinical features and management of rotavirus diarrhoea". Q. J. Med. 79 (288): 289–99. PMID 1649479.

- ^ Patel MM, Tate JE, Selvarangan R, et al. (2007). "Routine laboratory testing data for surveillance of rotavirus hospitalizations to evaluate the impact of vaccination" (Subscription required). Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 26 (10): 914–9. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e31812e52fd. PMID 17901797.

- ^ Pediatric ROTavirus European CommitTee (PROTECT) (2006). "The paediatric burden of rotavirus disease in Europe". Epidemiol. Infect. 134 (5): 908–16. doi:10.1017/S0950268806006091. PMC 2870494. PMID 16650331. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2870494.

- ^ Beards GM (1988). "Laboratory diagnosis of viral gastroenteritis". Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 7 (1): 11–3. doi:10.1007/BF01962164. PMID 3132369.

- ^ Steel HM, Garnham S, Beards GM, Brown DW (1992). "Investigation of an outbreak of rotavirus infection in geriatric patients by serotyping and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE)". J. Med. Virol. 37 (2): 132–6. doi:10.1002/jmv.1890370211. PMID 1321223.

- ^ "Gastroenteritis (cont.)". http://www.emedicinehealth.com/gastroenteritis/page5_em.htm#Exams%20and%20Tests. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ "Viral Gastroenteritis". http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/revb/gastro/faq.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ "www.cdc.gov". http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5841a2.htm.

- ^ "Viral Gastroenteritis". http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/viralgastroenteritis/#7. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ^ a b c "Diarrhoea and vomiting in children under 5". http://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG84#summary.

- ^ "Practice parameter: the management of acute gastroenteritis in young children. American Academy of Pediatrics, Provisional Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Acute Gastroenteritis". Pediatrics 97 (3): 424–35. 1996. PMID 8604285.

- ^ a b c Alhashimi D, Al-Hashimi H, Fedorowicz Z (2009). Alhashimi, Dunia. ed. "Antiemetics for reducing vomiting related to acute gastroenteritis in children and adolescents". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD005506. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005506.pub4. PMID 19370620.

- ^ "BestBets: Fluid Treatment of Gastroenteritis in Adults". http://www.bestbets.org/bets/bet.php?id=1039.

- ^ Canavan A, Arant BS (October 2009). "Diagnosis and management of dehydration in children". Am Fam Physician 80 (7): 692–6. PMID 19817339.

- ^ Gregorio GV, Gonzales ML, Dans LF, Martinez EG (2009). Gregorio, Germana V. ed. "Polymer-based oral rehydration solution for treating acute watery diarrhoea". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD006519. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006519.pub2. PMID 19370638.

- ^ a b "Managing Acute Gastroenteritis Among Children: Oral Rehydration, Maintenance, and Nutritional Therapy". http://www.cdc.gov/mmwR/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5216a1.htm.

- ^ "BestBets: Gradual introduction of feeding is no better than immediate normal feeding in children with gastro-enteritis". http://www.bestbets.org/bets/bet.php?id=390. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ^ a b King CK, Glass R, Bresee JS, Duggan C (November 2003). "Managing acute gastroenteritis among children: oral rehydration, maintenance, and nutritional therapy". MMWR Recomm Rep 52 (RR-16): 1–16. PMID 14627948. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5216a1.htm.

- ^ DeCamp LR, Byerley JS, Doshi N, Steiner MJ (September 2008). "Use of antiemetic agents in acute gastroenteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 162 (9): 858–65. doi:10.1001/archpedi.162.9.858. PMID 18762604.

- ^ Mehta S, Goldman RD (2006). "Ondansetron for acute gastroenteritis in children". Can Fam Physician 52 (11): 1397–8. PMC 1783696. PMID 17279195. http://www.cfp.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17279195.

- ^ Sturm JJ, Hirsh DA, Schweickert A, Massey R, Simon HK (May 2010). "Ondansetron use in the pediatric emergency department and effects on hospitalization and return rates: are we masking alternative diagnoses?". Ann Emerg Med 55 (5): 415–22. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.11.011. PMID 20031265.

- ^ "Ondansetron: Drug Information Provided by Lexi-Comp: Merck Manual Professional". http://www.merck.com/mmpe/print/lexicomp/ondansetron.html.

- ^ Traa BS, Walker CL, Munos M, Black RE (April 2010). "Antibiotics for the treatment of dysentery in children". Int J Epidemiol 39 Suppl 1: i70–4. doi:10.1093/ije/dyq024. PMC 2845863. PMID 20348130. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2845863.

- ^ Grimwood K, Forbes DA (December 2009). "Acute and persistent diarrhea". Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 56 (6): 1343–61. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2009.09.004. PMID 19962025.

- ^ Tytgat GN (2007). "Hyoscine butylbromide: a review of its use in the treatment of abdominal cramping and pain". Drugs 67 (9): 1343–57. PMID 17547475.

- ^ Allen SJ, Martinez EG, Gregorio GV, Dans LF (2010). Allen, Stephen J. ed. "Probiotics for treating acute infectious diarrhoea". Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11 (11): CD003048. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003048.pub3. PMID 21069673.

- ^ "Does yogurt decrease acute diarrhoeal symptoms in children with acute gastroenteritis". http://www.bestbets.org/bets/bet.php?id=1000.

- ^ Rehydrate.org: Zinc Supplementation

- ^ Patel A, Dibley MJ, Mamtani M, Badhoniya N, Kulkarni H (2009). "Zinc and copper supplementation in acute diarrhea in children: a double-blind randomized controlled trial". BMC Med 7: 22. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-7-22. PMC 2684117. PMID 19416499. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2684117.

- ^ "Diarrhoea and vomiting in children under 5". http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG84.

- ^ Parashar UD, Hummelman EG, Bresee JS, Miller MA, Glass RI (May 2003). "Global illness and deaths caused by rotavirus disease in children". Emerging Infect. Dis. 9 (5): 565–72. PMC 2972763. PMID 12737740. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2972763.

- ^ Victora CG, Bryce J, Fontaine O, Monasch R (2000). "Reducing deaths from diarrhoea through oral rehydration therapy". Bull. World Health Organ. 78 (10): 1246–55. PMC 2560623. PMID 11100619. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2560623.

- ^ Rudy's List of Archaic Medical Terms

- ^ "Biography of Zachary Taylor" from The White House

External links

- "NHS Direct: Gastroenteritis". http://www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk/checksymptoms/topics/gastroenteritis. Retrieved 2007-04-12.

- "The World Health Organisation: Diarrhoea". http://www.who.int/topics/diarrhoea/en/. Retrieved 2007-04-12.

- Gastroenteritis: First aid from the Mayo Clinic

Infectious diseases · Viral systemic diseases (A80–B34, 042–079) Oncovirus Immune disorders Central

nervous systemEncephalitis/

meningitisDNA virus: JCV (Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy)

RNA virus: MeV (Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis) · LCV (Lymphocytic choriomeningitis) · Arbovirus encephalitis · Orthomyxoviridae (probable) (Encephalitis lethargica) · RV (Rabies) · Chandipura virus · Herpesviral meningitis · Ramsay Hunt syndrome type IIEyeCardiovascular Respiratory system/

acute viral nasopharyngitis/

viral pneumoniaDigestive system Urogenital Inflammation Acute preformed: Lysosome granules · vasoactive amines (Histamine, Serotonin)

synthesized on demand: cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-8, TNF-α, IL-1) · eicosanoids (Leukotriene B4, Prostaglandins) · Nitric oxide · KininsChronic Processes Traditional: Rubor · Calor · Tumor · Dolor (pain) · Functio laesa

Modern: Acute-phase reaction/Fever · Vasodilation · Increased vascular permeability · Exudate · Leukocyte extravasation · ChemotaxisSpecific locations CNS (Encephalitis, Myelitis) · Meningitis (Arachnoiditis) · PNS (Neuritis) · eye (Dacryoadenitis, Scleritis, Keratitis, Choroiditis, Retinitis, Chorioretinitis, Blepharitis, Conjunctivitis, Iritis, Uveitis) · ear (Otitis, Labyrinthitis, Mastoiditis)CardiovascularCarditis (Endocarditis, Myocarditis, Pericarditis) · Vasculitis (Arteritis, Phlebitis, Capillaritis)upper (Sinusitis, Rhinitis, Pharyngitis, Laryngitis) · lower (Tracheitis, Bronchitis, Bronchiolitis, Pneumonitis, Pleuritis) · MediastinitisDigestivemouth (Stomatitis, Gingivitis, Gingivostomatitis, Glossitis, Tonsillitis, Sialadenitis/Parotitis, Cheilitis, Pulpitis, Gnathitis) · tract (Esophagitis, Gastritis, Gastroenteritis, Enteritis, Colitis, Enterocolitis, Duodenitis, Ileitis, Caecitis, Appendicitis, Proctitis) · accessory (Hepatitis, Cholangitis, Cholecystitis, Pancreatitis) · PeritonitisArthritis · Dermatomyositis · soft tissue (Myositis, Synovitis/Tenosynovitis, Bursitis, Enthesitis, Fasciitis, Capsulitis, Epicondylitis, Tendinitis, Panniculitis)

Osteochondritis: Osteitis (Spondylitis, Periostitis) · Chondritisfemale: Oophoritis · Salpingitis · Endometritis · Parametritis · Cervicitis · Vaginitis · Vulvitis · Mastitis

male: Orchitis · Epididymitis · Prostatitis · Balanitis · Balanoposthitis

pregnancy/newborn: Chorioamnionitis · OmphalitisCategories:- Pediatrics

- Foodborne illnesses

- Infectious diseases

- Inflammations

- Abdominal pain

- Conditions diagnosed by stool test

- Noninfective enteritis and colitis

- Diarrhea

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.