- Constitution of May 3, 1791

-

Constitution of May 3, 1791

May 3rd Constitution, by Matejko (1891). King Stanisław August (left) enters St. John's Cathedral, where deputies will swear to uphold the Constitution. Background: Warsaw's Royal Castle, where it has just been adopted.Created October 6, 1788 – May 3, 1791 Ratified May 3, 1791 Authors King Stanisław August Poniatowski, Stanisław Małachowski, Hugo Kołłątaj, Ignacy Potocki, Stanisław Staszic, Scipione Piattoli, others The Constitution of May 3, 1791 (Polish: Konstytucja Trzeciego Maja; Lithuanian: Gegužės trečiosios konstitucija) was adopted as a "Government Act" (Polish: Ustawa rządowa) on that date by the Sejm (parliament) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Historian Norman Davies calls it "the first constitution of its type in Europe"; other scholars also refer to it as the world's second oldest constitution.[1][2][3][4][a] It was in effect for only a year, until the Russo-Polish War of 1792.

The May 3rd Constitution was designed to redress long-standing political defects of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and its traditional system of "Golden Liberty" conveying disproportionate rights and privileges to the nobility. The Constitution introduced political equality between townspeople and nobility (szlachta) and placed the peasants under the protection of the government, thus mitigating the worst abuses of serfdom. The Constitution abolished pernicious parliamentary institutions such as the liberum veto, which at one time had put the sejm at the mercy of any deputy who might choose, or be bribed by an interest or foreign power, to undo legislation passed by that sejm. The Constitution sought to supplant the existing anarchy fostered by some of the country's magnates with a more democratic constitutional monarchy.

The adoption of the May 3rd Constitution provoked the active hostility of the Commonwealth's neighbors. In the War in Defense of the Constitution, the Commonwealth lost its Prussian ally, Frederick William II, when the Commonwealth failed to live up to territorial agreements made in their treaty and also failed to consult Prussia before agreeing on the constitution. It was then defeated by Catherine the Great's Imperial Russia allied with the Targowica Confederation, a coalition of Polish magnates and landless nobility who opposed reforms that might weaken their influence. Despite the Commonwealth's defeat and the consequent Second Partition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the May 3 Constitution influenced later democratic movements. It remained, after the demise of the Polish Republic in 1795, over the next 123 years of Polish partitions, a beacon in the struggle to restore Polish sovereignty. In the words of two of its co-authors, Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj, it was "the last will and testament of the expiring Country."[5][b]

Contents

Background

End of the Golden Age

Main articles: History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1648–1764) and History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1764–1795)The May 3rd Constitution responded to the increasingly perilous situation of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth,[6] only a century earlier a major European power and indeed the largest state on the continent.[7] Already two hundred years before the May 3rd Constitution, King Sigismund III Vasa's court preacher, the Jesuit Piotr Skarga, had famously condemned the individual and collective weaknesses of the Commonwealth.[8] Likewise, in the same period, other writers and philosophers such as Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski[9] and Wawrzyniec Grzymała Goślicki[10] and Jan Zamoyski's egzekucja praw (Execution-of-the-Laws) reform movement, had advocated reforms.[11]

Rejtan, by Matejko. In September 1773, Rejtan (lower right) tried to prevent ratification of the First Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by barring other Sejm deputies from the chamber.

Rejtan, by Matejko. In September 1773, Rejtan (lower right) tried to prevent ratification of the First Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by barring other Sejm deputies from the chamber.

As they failed, the state machinery became increasingly dysfunctional. Many historians hold that a major cause of the Commonwealth's downfall was the peculiar parliamentary institution of the liberum veto ("free veto"), which since 1652 had in principle permitted any Sejm deputy to nullify all the legislation that had been adopted by that Sejm.[12] This has set up a dangerous precedent.[12] Thus deputies bribed by magnates or foreign powers (primarily from Russian Empire, Kingdom of Prussia and France), or simply content to believe they were living in some kind of "Golden Age", for over a century paralysed the Commonwealth's government.[12][13] The threat of the liberum veto could be overridden by the establishment of a "confederated sejm", which operated immune from the liberum veto, but that was not a common occurrence.[14]

By the early 17th century, the magnates of Poland and Lithuania controlled the state—or rather, they managed to ensure that no reforms would be carried out that might weaken their privileged status (the "Golden Freedoms").[15] They spent lavishly on banquets, drinking bouts and other amusements, while the peasants languished in abysmal conditions and the towns, many of which were wholly within the private property of a magnate who feared the rise of an independent middle class, were kept in a state of ruin.[15][16]

The matters were not helped by the inefficient monarchs elected to the Commonwealth throne at the turn of the century:[17] Augustus II the Strong and Augustus III of Poland of the House of Wettin. The Wettins, used to the absolute rule, attempted to rule through intimidation and the use of force, which led to the a series of conflicts between Wettin supporters and opponents (including another pretender to the Polish throne, King Stanisław Leszczyński).[17] Those conflicts often took the form of the confederations - legal rebellions against the king permitted under the Golden Freedoms (some conflicts of that era included the Warsaw Confederation, Sandomierz Confederation, Tarnogród Confederation, Dzików Confederation and the War of the Polish Succession).[17] Only 8 out 18 sejm sessions during the reign of Augustus II passed legislation.[18] For a period in 30 years around the reign of Augustus III, only one session was able to pass legislation.[19] The government was near collapse, giving rise to the term "Polish anarchy", and the country was managed by provincial assemblies and magnates.[19]

There were also reform attempts in the Wettin era, led by individuals such as Kazimierz Karwowski, Stanisław Dunin-Karwicki, Stanisław A. Szczuka and Józef Massalski, however, they also proved to be for the most part futile.[13][17]

King Stanisław August, principal author of Constitution. A year later he acquiesced in its overthrow.

King Stanisław August, principal author of Constitution. A year later he acquiesced in its overthrow.

Early reforms

The Enlightenment had gained great influence in certain Commonwealth circles during the reign (1764–95) of its last king, Stanisław August Poniatowski. Poniatowski, a Polish magnate, had been a deputy to the Sejms of 1750, 1758, 1760, 1761, 1762 and 1764, and as such had a much deeper understandings of Polish politics than previous monarchs elected to the Polish throne.[20] In 1764 the liberum veto had been weakened, made no longer applicable to "economic matters" such as taxation.[20][21] Poniatowski had proceeded with cautious reforms such as the establishment of fiscal and military ministries and a national customs tariff. However, the idea of reforming the Commonwealth was viewed with suspicion not only by its magnates but also by neighboring countries, which were content with the state of the Commonwealth's affairs and abhorred the thought of a resurgent and democratic power on their borders.[22]

Accordingly Russia's Empress Catherine the Great and Prussia's King Frederick the Great provoked a conflict between some members of the Sejm and the King over civil rights for religious minorities (the Protestants and the Greek Orthodox).[21][23][24] Catherine and Frederick declared their support for the Polish nobility (szlachta) and their "liberties," and by October 1767 Russian troops had assembled outside the Polish capital, Warsaw, in support of the conservative Radom Confederation.[23][24][25] The King and his adherents, in face of superior Russian military force, were left with little choice but to acquiesce in Russian demands and during the Repnin Sejm (named after unofficially presiding Russian ambassador Nicholas Repnin) accept the five "eternal and invariable principles" which Catherine vowed to "protect for all time to come in the name of Poland's liberties": the election of kings; the right of liberum veto; the right to renounce allegiance to, and raise rebellion against, the king (rokosz); the szlachta's exclusive right to hold office and land; and a landowner's power of life and death over his peasants.[21][22][23][24] Thus all the privileges of the nobility that had made the Commonwealth's political system ("Golden Liberty") ungovernable were guaranteed as unalterable in the Cardinal Laws.[23][24][25] During the 1768 Sejm, Repnin showed his influence in the Commonwealth by arranging the abduction and imprisonment (untli 1773) of three vocal opponents: Kajetan Sołtyk, Józef A. Załuski, Wacław Rzewuski and Seweryn Rzewuski.[26] The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth thus has been shown to be, effectively, a protectorate of the Russian Empire.[27] Nonetheless, several minor beneficial reforms were adopted (such as restoration of full political rights to the religious minorities), and the need for more reforms was becoming increasingly recognized.[24][26]

Not everyone in the Commonwealth agreed with King Stanisław August's acquiescence to the Russian intervention. On February 29, 1768, several magnates, including Józef Pułaski and his young son, Kazimierz Pułaski (Casimir Pulaski), vowing to oppose Russian influence, declared Stanisław August a lackey of Russia and Catherine and formed a confederation at the town of Bar.[26][28][29] The Bar Confederation, despite it patriotic focus on limiting the influence of foreigners in the Commonwealth affairs, was also rather conservative, and restrictive with regards to religious tolerance.[28] A civil war begun in Poland, waged by the Confederation with the goal of overthrowing the King and fought on until 1772, when overwhelmed by Russian intervention.[22]

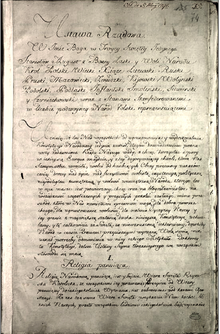

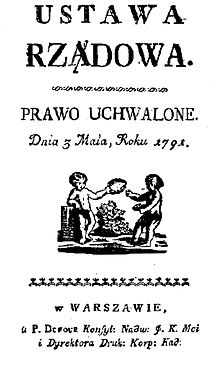

In 1791, the "Great" or Four-Year Sejm of 1788–92 adopted the May 3 Constitution at Warsaw's Royal Castle.

In 1791, the "Great" or Four-Year Sejm of 1788–92 adopted the May 3 Constitution at Warsaw's Royal Castle.

Royal Castle Senate Chamber, where the May 3rd Constitution was adopted

Royal Castle Senate Chamber, where the May 3rd Constitution was adopted

The Bar Confederation's defeat set the scene for the next act in the unfolding drama.[28] On August 5, 1772, at St. Petersburg, Russia, the three neighboring powers—Russia, Prussia and Austria—signed the First Partition treaty. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was to be divested of about a third of its territory and population (over 200,000 km2 (77,220 sq mi) and 4 million people).[30] This was justified on grounds of "anarchy" in the Commonwealth and her refusal to cooperate with its neighbors' efforts to restore order.[31] The three powers demanded that the Sejm ratify this first partition, otherwise threatening further partitions. King Stanisław August yielded under duress and on April 19, 1773, called the Sejm into session. Only 102 deputies attended what became known as the Partition Sejm; the rest, aware of the King's decision, refused. Despite protests, notably by the deputy Tadeusz Rejtan, the First Partition of Poland was ratified.[30]

The first of the three successive 18th-century partitions of Commonwealth territory that would eventually blot Poland from the map of Europe shocked the inhabitants of the Commonwealth, and had made it clear to progressive minds that the Commonwealth must either reform or perish.[30] In the last three decades preceding the constitution, there was a rising interest among progressive thinkers in constitutional reform.[32] Even before the First Partition, a Polish noble, Michał Wielhorski, and envoy of the Bar Confederation, had been sent to ask the French philosophes Gabriel Bonnot de Mably and Jean-Jacques Rousseau to offer suggestions on a new constitution for a new Poland.[33][34][35][36] Mably had submitted his recommendations (The Government and Laws of Poland) in 1770–71; Rousseau had finished his Considerations on the Government of Poland in 1772, when the First Partition was already underway.[37] Notable works advocating the need to reform and presenting specific solutions were published in the Commonwealth itself by Polish-Lithuanian thinkers such as Stanisław Konarski (On the Effective Conduct of Debates in Ordinary Sejms, 1761–1763), founder of the Collegrium Nobilium; Józef Wybicki (Political Thoughts on Civil Liberties, 1775, Patriotic Letters, 1778-1778), composer of the Polish National Anthem; Hugo Kołłątaj (Anonymous Letters to Stanisław Małachowski, 1788–1789, The Political Law of the Polish Nation, 1790), head of the Kołłątaj's Forge party; and Stanisław Staszic (Remarks on the Life of Jan Zamoyski, 1787).[36][38] Also seen as crucial to giving the Constitution moral and political support were Ignacy Krasicki's satires of the Great Sejm era.[39]

Supported by more progressive magnates, such as the Czartoryski family, and King Stanisław August, a new wave of reforms were introduced at the Partition Sejm.[25][40][41] The most important included the establishment, in 1773, of a Komisja Edukacji Narodowej ("Commission of National Education")—the first ministry of education in the world.[30][41][42][43] New schools were opened in the cities and in the countryside, uniform textbooks were printed, teachers were educated, and poor students were provided scholarships.[30][41] The Commonwealth's military was modernized, and a standing army was formed. Economic and commercial reforms, previously shunned as unimportant by the szlachta, were introduced.[40][41] Finally, a new executive body was created, the 36-strong Permanent Council, comprising five ministries with limited legislative powers, giving the Commonwealth a new governing body, in constant session between the Sejms and immune to liberum veto.[25][30][40][41]

In 1776, the Sejm commissioned Chancellor Andrzej Zamoyski to draft a new legal code, the Zamoyski Code.[32] By 1780, under Zamoyski's direction, a code (Zbiór praw sądowych) had been produced. It would have strengthened royal power, made all officials answerable to the Sejm, placed the clergy and their finances under state supervision, and deprived landless szlachta of many of their legal immunities. Zamoyski's progressive legal code, containing elements of constitutional reform, facing opposition from conservative szlachta and foreign powers, failed to be adopted by the Sejm.[32][44]

Adoption and aftermath

The Great Sejm

Main article: Great SejmA major opportunity for reform seemed to present itself during the "Four-Year" or "Great Sejm" of 1788–92, which opened on 6 October 1788 with 181 deputies, and from 1790—in the words of the May 3 Constitution's preamble—met "in dual number", the 171 newly elected Sejm deputies having joined the earlier-established Sejm.[25][38][45] On its second day the Sejm transformed itself into a confederated sejm to make it immune to the threat of the liberum veto.[38][46]

Events in the world appeared to play into the reformers' hands.[25] Poland's neighbors were too occupied with wars to intervene forcibly in Poland, with Russia and Austria engaged in hostilities with the Ottoman Empire (the Russo-Turkish War, 1787-1792 and the Austro-Turkish War (1787–1791)); the Russians also found themselves fighting Sweden (the Russo-Swedish War (1788–1790)).[25][47][48][49][50] A new alliance between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Prussia seeming to provide security against Russian intervention, King Stanisław August drew closer to leaders of the reform-minded Patriotic Party.[25][49][51][52][53]

The Sejm adopted several smaller reforms before the final constitution, on towns and burgher rights, and on the voting rights.[54][55] While the Sejm comprised representatives only of the nobility and clergy, the reformers were supported by the burghers (townspeople), who in the fall of 1789 organized a Black Procession, demonstrating their desire to be part of the political process.[53] Taking a cue from similar events in France, and with the fear that if burghers' demands were not met, their peaceful protests could turn violent, the Sejm on 18 April 1791 adopted a law addressing the status of the cities and the rights of the burghers (the Free Royal Cities Act).[56]

Reforms were opposed by conservative elements, including the Hetmans' Party.[38][57] [58] The draft Constitution's advocates, threatened with violence from their opponents, and while many opposed deputies were still away on Easter recess, managed to move debate on the Government Act forward by two days from the original 5 May.[59] The ensuing debate and adoption of the Government Act took place in a quasi-coup d'etat: recall notices were not sent to known opponents of reform, while many pro-reform deputies arrived early and in secret, and the royal guard were positioned about the Royal Castle, where the Sejm was gathered, to prevent Russian adherents from disrupting the proceedings.[59] On 3 May the Sejm met with only 182 members present, about a third of its "dual" number.[59][55]

The new Constitution had been drafted by the King, with contributions from others, including Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj.[39][25] The King is credited with authoring the general provisions, and Kołłątaj, with giving the work its final shape.[39]

The bill (the "Government Act") was read out and adopted overwhelmingly, to the enthusiasm of the crowds gathered outside.[60] Soon afterwards, the Society of Friends of the Government Ordinance (Zgromadzenie Przyjaciół Konstytucji Rządowej), an organization including many participants of the Great Sejm and aiming to defend the reforms already enacted and to promote further ones, was formed.[39] The response was however less enthusiastic in the provinces, where the Hetmans' Party influence was stronger.[60]

War in Defense of the Constitution

Main article: Polish–Russian War of 1792The Constitution remained in effect for only a year before being overthrown, by Russian armies allied with the Targowica Confederation, in the Polish–Russian War of 1792, also known as the War in Defense of the Constitution.[60]

Wars between Turkey and Russia and Sweden and Russia having by now ended, Empress Catherine was furious over the adoption of the May 3 Constitution, which threatened Russian influence in Poland.[48][61][50] Russia had viewed Poland as a de facto protectorate.[62] The contacts of Polish reformers with the Revolutionary French National Assembly were seen by Poland's neighbors as evidence of a revolutionary conspiracy and a threat to the absolute monarchies.[63][64] The Prussian statesman Ewald von Hertzberg expressed the fears of European conservatives: "The Poles have given the coup de grâce to the Prussian monarchy by voting a constitution."[65]

A number of magnates who had opposed the Constitution from the start, such as Franciszek Ksawery Branicki, Szymon and Józef Kossakowski, Stanisław Szczęsny Potocki and Seweryn Rzewuski asked Tsarina Catherine to intervene and restore their privileges (the cardinal laws) abolished under the Constitution.[60] To that end these magnates formed the Targowica Confederation.[60] The Confederation's proclamation, prepared in St. Petersburg in January 1792, criticized the Constitution for contributing to, in their own words, "contagion of democratic ideas" following "the fatal examples set in Paris".[66][67] It asserted that "The parliament... has broken all fundamental laws, swept away all liberties of the gentry and on the third of May 1791 turned into a revolution and a conspiracy."[68] The confederates declared to overcame this revolution, they "can do nothing but turn trustingly to Tsarina Catherine, a distinguished and fair empress our neighboring friend and ally", who "respects the nation's need for well-being and always offers it a helping hand."[68]

On May 18, 1792, over 20,000 Confederates crossed the border into Poland, together with 97,000 veteran Russian troops. The Sejm voted to increase the Polish Army to 100,000, but due to insufficient time and funds, this number was never reached.[60] The Polish King and the reformers could field only a 37,000-man army, many of them untested recruits. This army, under the command of King's nephew Józef Poniatowski and Tadeusz Kościuszko, did defeat or fought to the draw the Russians on several occasions, but in the end, the defeat loomed inevitable.[60] Eventually, the King himself dealt a deathblow to the Polish cause: when in July 1792 Warsaw was threatened with siege by the Russians, the King came to believe that victory was impossible against the Russian numerical superiority, and that surrender was the only alternative to total defeat and a massacre of the reformers. On July 24, 1792, King Stanisław August Poniatowski abandoned the reformist cause and joined the Targowica Confederation.[60] The Polish Army disintegrated. Many reform leaders, believing their cause lost, went into self-exile. The King had not saved the Commonwealth, however. To the surprise of the Targowica Confederates, there ensued the Second Partition of Poland.[67][60] With the new deputies bribed or intimated by the Russian troops, the infamous Grodno Sejm took place.[60][69] Russia took 250,000 square kilometres (97,000 sq mi), and Prussia took 58,000 square kilometres (22,000 sq mi).[69] The Commonwealth now comprised no more than 212,000 square kilometres (82,000 sq mi). What was left of the Commonwealth was merely a small buffer state with a puppet king and a Russian army.

For a year and a half, Polish patriots bided their time, while planning an insurrection.[69] On March 24, 1794, in Kraków, Tadeusz Kościuszko declared what has come to be known as the Kościuszko Uprising.[69] On May 7 he issued the "Proclamation of Połaniec" (Uniwersał Połaniecki), granting freedom to the peasants and ownership of land to all who fought in the insurrection. Revolutionary Tribunals meted summary justice to those deemed traitors to the Commonwealth.[69]

After some initial victories—the Battle of Racławice (April 4) and the capture of Warsaw (April 18) and Wilno (April 22)—the Uprising was dealt a crippling blow: the forces of Russia, Austria and Prussia joined in a military intervention.[70] Historians consider the Uprising's defeat to have been a foregone conclusion in face of the gigantic numerical superiority of the three invading powers. The defeat of Kościuszko's forces led in 1795 to the third and final partition of the Commonwealth.[70]

Features

The Polish constitution was one of several of its time reflecting similar Enlightenment influences, including Montesquieu's advocacy of a separation and balance of powers among the three branches of government—so that, in the words of the May 3 Constitution (article V), "the integrity of the states, civil liberty, and social order remain always in equilibrium"—as well as Montesquieu's advocacy of a bicameral legislature.[25][71] According to Jacek Jędruch, the constitution, in its liberality of provisions, "fell somewhere blow the French, above the Canadian, and left the Prussian far behind", but was "no match for the American Constitution".[55] King Stanisław August Poniatowski described the May 3 Constitution, according to a contemporary account, as "founded principally on those of England and the United States of America, but avoiding the faults and errors of both, and adapted as much as possible to the local and particular circumstances of the country."[72] George Sanford notes that the May Constitution gave Poland "a constitutional monarchy close to the English model of the time."[25]

The Constitution comprised 11 articles, following a preamble.[25] It introduced the principle of popular sovereignty (applied to the nobility and townspeople) and a separation of powers into legislative (a bicameral Sejm), executive ("the King in his council") and judicial branches.[71]

The Constitution advanced the democratization of the polity by limiting the excessive legal immunities and political prerogatives of landless nobility, while granting to the townspeople—in the earlier Miasta Nasze Królewskie Wolne w Państwach Rzeczypospolitej (Free Royal Cities Act) of April 18 (or 21), 1791, stipulated in Article III to be integral to the Constitution—personal security (neminem captivabimus), the right to acquire landed property, and eligibility for military officers' commissions, public offices, including reserved seats in the Sejm itself and in the executive commissions of the Treasury, the Police and the Judiciary, and membership in the nobility (szlachta).[56][73][74][75]

Prawo o sejmikach, the act on regional sejms (sejmiki), passed earlier on March 24, 1791 (article VI), was similarly recognized.[76][55] This law introduced major changes to the electoral ordinance, as it reduced the enfranchisement of the noble class; previously, all nobles had been eligible to vote in the sejmiks (local parliaments), which de facto meant that many of the poorest, landless nobles (known as "clients" or "clientele") voted as local magnates bade them.[54][77][78][59][25] The voting right was tied to a property qualification (one had to own or lease the land and pay taxes, or be closely related to such a person, to be eligible to vote).[79][55] Active voting rights were also taken from nobles who held property granted them by magnates or the king, to remove the temptation to vote so as to please their benefactors.[54] Some 300,000 of 700,000 otherwise eligible nobles were thus disfranchised, much to their displeasure.[54] Voting rights were also restored to landowners who were in military service (rights that they had lost in 1775).[54] Less controversially for its time, the voting was limited to males of 18 years of age.[74] The eligible voters would elect deputies to the local (county, Polish: powiat) sejmiks, which elected deputies to the general Sejm.[74]

With half the nobility disfranchised, and some half million burghers in the Commonwealth now substantially enfranchised, the Great Sejm's early acts did much to increase equality in the distribution of political power (though the situation of less politically conscious and active classes, notably the Jews and peasants, still waited to be addressed).[47][75][c] While the Government Act also placed the Commonwealth's peasantry "under the protection of the national law and government" — a first step toward ending serfdom and enfranchising the country's largest and most oppressed social class — the peasant question was far from resolved, as serfdom remained in force; it would take the Second Partition and Tadeusz Kościuszko's Proclamation of Połaniec to move the matter forward.[25][47][74][75][c]

Legislative power, as specified by the Article VI, rested with the bicameral parliament (elective Sejm and appointive Senate) and the king.[74][80] The May 3rd Constitution provided for a Sejm, "ordinarily" meeting every two years and "extraordinarily" whenever required by a national emergency (as the Sejm was to be ready to be called into session at any time of need).[74][80] Its lower chamber—the Chamber of Deputies (Izba Poselska)—comprised 204 deputies(2 from each powiat, 68 each from the provinces of Greater Poland, Lesser Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania) and 21 plenipotentiaries of royal cities (7 from each province).[74][25] The royal chancellery should inform the sejmiks of the legislation in intended to propose in advance, so that the deputies would have time to prepare for the discussions in Sejm.[80] Not only the king, but also all deputies had legislative initiative, and most matters (peace, commercial treaties, budget, war taxes, currency issues, education, police and treasury organization, request of regional administration) required simple majority.[74] Two-thirds majority was required for treaties of alliance, declaration of war, army complement, increases in national debt, and a three-fourth majority vote was needed for change to permanent taxation.[74] Sejm'supper chamber—the Chamber of Senators (Izba Senacka)—comprised 130[74]-132[25] (sources vary) senators (voivodes, castellans, bishops and — without the right to vote — government ministers).[25][74] The Senate was presided over by the king, who had one vote in it that could be used to break the ties.[74] The senate had a suspensive veto over the laws that the Sejm passed, applicabe till the next election.[74]

Executive power, according to Article VIII, was in the hands of a royal council, a cabinet of ministers called the Guard of the Laws (or Guardians of Law, Polish: Straż Praw).[25][74][81] The ministries could not create or interpret the laws, and all acts of the foreign ministry were provisional, subject to Sejm's approval.[81] This council was presided over by the King and comprised the Roman Catholic Primate of Poland (who was also president of the Education Commission) and five ministers appointed by the King: a minister of police, minister of the seal (i.e. of internal affairs — the seal was a traditional attribute of the earlier Chancellor), minister of the seal of foreign affairs, minister belli (of war), and minister of treasury.[74] In addition to the ministers, council members included — without a vote — the Crown Prince, the Marshal of the Sejm, and two secretaries.[81] This royal council was a descendant of the similar council that had functioned over the previous two centuries since King Henry's Articles (1573). Acts of the King required the countersignature of the respective minister.[82] The stipulation that the King, "doing nothing of himself, [...] shall be answerable for nothing to the nation," parallels the British constitutional principle that "The King can do no wrong." (In both countries, the respective minister was responsible for the king's acts.)[83][82] The ministers, however, were responsible to the Sejm, which could dismiss them by a two-third vote of no confidence by the members of both houses.[25][55][74] Ministers could be also held accountable by the Sejm court, and the Sejm could demand an impeachement trial of a minister with a simple majority vote.[25][82] The king was the nation's commander-in-chief, commanding its armies; the institution of the hetman was not mentioned in the Constiution.[82] The decisions of the royal council were carried out by commissions, including the previously created Commission of National Education, and the new commissions for Police, the Military and the Tresury, whose members were elected by the Sejm.[82]

Article X stressed the importance of the education of the royal children, and tasked the Commission of National Education with this responsibility.[84]

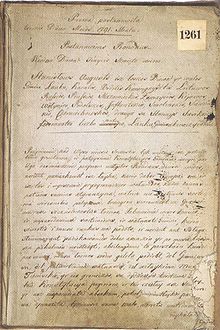

Manuscript 1791 Lithuanian translation

Manuscript 1791 Lithuanian translation

To enhance Commonwealth integration and security, the Constitution abolished the erstwhile union of Poland and Lithuania in favor of a unitary state.[39] Related acts included the "Deklaracja Stanów Zgromadzonych (Declaration of the Assembled Estates) of May 5, 1791, confirming the Government Act adopted two days earlier, and the Zaręczenie Wzajemne Obojga Narodów (Reciprocal Guarantee of Two Nations, i.e., of the Crown of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania) of October 22, 1791, affirming the unity and indivisibility of Poland and the Grand Duchy within a single state, and their equal representation in state-governing bodies.[72][85] The Mutual Declaration strengthened the Polish-Lithuanian union, while keeping many federal aspects of the state intact.[86] The document was translated into Lithuanian.[87]

Constitutions

Constitutions

of PolandThe Constitution abolished several institutional sources of government weakness and national anarchy, including the liberum veto (replaced by a simple majority vote), confederations and confederated sejms (paradoxically, the Great Sejm was itself a confederated sejm), and the excessive sway of sejmiks (regional sejms) stemming from the binding nature of their instructions to their Sejm deputies.[25][55] The confederations were declared "contrary to the spirit of this Constitution, subversive of government and destructive of society".[81] Thus it strengthened the powers of the parliament (sejm) proper, moving the country closer towards a constitutional monarchy.[25][55] The constitution also changed the government from an elective (in its unique Polish variant) to hereditary monarchy.[25][88][55] The latter provision was meant to reduce the destructive vying influences of foreign powers at each royal election.[89][d] The royal dynasty itself, was, however, elective, and if it was to die out, a new one would be chosen by "the Nation".[81] In the period when regency was needed, the royal council would take that responsibility (as covered by Article IX).[84] The king held the throne "by the grace of God and the will of the Nation," and noted that "all authority derives from the will of the Nation."[25][74] The institution of pacta conventa was preserved.[82] On Stanisław August's death the Polish throne would become hereditary and pass to Frederick Augustus I of Saxony, of the house of Wettin, which had provided two of Poland's recent elective kings (his daughter, Maria Augusta Nepomucena, was called the infanta of Poland).[55][82] This provision was contingent upon Frederic Augustus agreement, and he in fact declined the offer presented to him by Adam Czartoryski.[55] He would change his mind ten years later, when Napoleon convinced him to become the king of the short-lived Duchy of Warsaw.[39]

Judiciary, discussed in Article VIII, was separated from the two other branches of the government.[74][82] Justice was to be served by elective judges.[74] Court of first instance existed in each voivodeship, and were in constant session.[74] Appellate tribunals were established for the provinces, based on the reformed Crown Tribunal and Lithuanian Tribunal.[74] The Sejm also elected from its deputies the judges for the Sejm court (a precursor for the modern State Tribunal of Poland).[74][82] Referendary courts of each province were to hear the cases of peasantry.[82] Municipal courts, describied in the law on the towns, complemented this system.[82]

The Constitution's Article I acknowledged the Roman Catholic faith as the "dominant religion", but guaranteed tolerance of, and freedom to, all religions.[25][50] Article II confirmed many old privileges of the nobility, stressing that all nobles are equal, enjoy personal security and the right to property.[75] The Army was to be built up to 100,000 men.[90] The constitution also provided additional levies on the nobility and clergy.[91]

The May 3 Constitution remained to the last a work in progress. The provisions of the Government Act were fleshed out in a number of laws passed in May–June 1791 on sejms and sejm courts (two acts of May 13), the Guardians of the Laws (June 1), the national police commission (that is, ministry; June 17) and municipal administration (June 24). The constitution included provisions for its own revision, to be handled by an extraordinary Sejm held every 25 years.[55][80] Co-author Hugo Kołłątaj announced that work was underway on "an economic constitution…guaranteeing all rights of property [and] securing protection and honor to all manner of labor…". Yet a third basic law was touched on by Kołłątaj: a "moral constitution," most likely a Polish analog to the American Bill of Rights and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen.[92] A new civil and criminal code was in the works.[84]

Legacy

Significance

Unfinished Temple of Divine Providence, in Warsaw's Botanical Gardens, at Ujazdów Avenue. Cornerstone was laid 3 May 1792, to commemorate the Constitution of May 3, 1791, by King Stanisław August Poniatowski and his brother, Primate Michał Jerzy Poniatowski.

Unfinished Temple of Divine Providence, in Warsaw's Botanical Gardens, at Ujazdów Avenue. Cornerstone was laid 3 May 1792, to commemorate the Constitution of May 3, 1791, by King Stanisław August Poniatowski and his brother, Primate Michał Jerzy Poniatowski.

The memory of the May 3rd Constitution—recognized by political scientists as a very progressive document for its time—for generations helped keep alive Polish aspirations for an independent and just society, and continued to inform the efforts of its authors' descendants.[25] In Poland it is viewed as a national symbol, and the culmination of all that was good and enlightened in Polish history and culture.[25] In the words of two of its co-authors, Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj, it was "the last will and testament of the expiring Country."[5] The May 3rd anniversary of its adoption has been observed as Poland's most important civil holiday since Poland regained independence in 1918.[93]

Historians agree that the constitution has a limited practical impact, being in force for over the year.[70] What is seen as much more important, however, is its significance as a sign of moral regeneration, in mobilizing the country citizens and making them concerned wit the political well-being of their country.[70]

Prior to the May 3rd Constitution, in Poland the term "constitution" (Polish: konstytucja) had denoted all the legislation, of whatever character, that had been passed at a Sejm. Only with the adoption of the May 3 Constitution did konstytucja assume its modern sense of a fundamental document of governance.

These charters of government form an important milestone in the history of democracy. Poland and the United States, though distant geographically, showed some notable similarities in their approaches to the design of political systems.[94] By contrast to the great absolute monarchies, both countries were remarkably democratic. The kings of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth were elected, and the Commonwealth's parliament (the Sejm) possessed extensive legislative authority. Under the May 3rd Constitution, Poland afforded political privileges to its townspeople and to its nobility (the szlachta), which formed some ten percent of the country's population. This percentage closely approximated the extent of political access in contemporary America, where effective suffrage was limited to male property owners.

The defeat of Poland's liberals was but a temporary setback to the cause of democracy. The destruction of the Polish state only slowed the expansion of democracy, by then already established in North America. Democratic movements soon began undermining the absolute monarchies of Europe. The May 3 Constitution was translated, in abridged form, into French, German and English. French revolutionaries toasted King Stanisław August and the Constitution—not only for their progressive character, but because the War in Defense of the Constitution and the Kościuszko Uprising tied up appreciable Russian and Prussian forces that could not therefore be used against Revolutionary France. Thomas Paine regarded the May 3 Constitution as a great breakthrough. Edmund Burke described it as "the noblest benefit received by any nation at any time... Stanislas II has earned a place among the greatest kings and statesmen in history."[71][89] In the end, the conservatives managed to delay the ascent of democracy in Europe only for a century; after the First World War, most of the European absolute monarchies were replaced by democratic states, including the reborn, Second Polish Republic.

The constitution was a milestone in the Polish - and world's - legal history, as well as history of democracy.[4][94] It was the first constitution to follow the 1788 ratification of the United States Constitution.[94][95] Lapoint and Wolenski calls it "the second constitution in history".[3] Albert Blaustein refers to it as the "world's second national constitution",[1] and Bill Moyers says it was "Europe's first codified national constitution (and the second oldest in the world)."[2] Norman Davies calls it "the first constitution of its type in Europe".[4][d]

Holiday

Main article: May 3rd Constitution DayMay 3rd was first declared a holiday (May-3rd-Constitution Day—Święto Konstytucji 3 Maja) on May 5, 1791.[96] Banned during the partitions of Poland, it was again made an official Polish holiday in April 1919 under the Second Polish Republic—the first holiday officially introduced in the Second Polish Republic.[93][96][97] The May 3 holiday was banned once more during World War II by the Nazi and Soviet occupiers. It was celebrated in the Polish cities in May 1945, although in a mostly spontaneous manner.[93] The anti-communist demonstrations that took place around that day a year later and the competition the date created with the communist-endorsed May 1 Labor Day celebrations led in the Polish People's Republic to its rebranding (to Democratic Party Day) and removal from the list of national holidays by 1951.[93][96] Until 1989, May 3 was a common day for anti-government and anti-communist protests.[93] May 3 was restored as an official Polish holiday in April 1990, after the fall of communism.[96] In 2007, May 3 was also declared a Lithuanian national holiday.[98]

Polish Constitution Day has been a focal point of ethnic celebrations of Polish-American pride in the Chicago area, going back to 1892.[99] Poles in Chicago have continued this tradition to the present day, marking it with festivities and the annual Polish Constitution Day Parade.[99][100]

See also

Notes

a ^ The claims of "first" and "second constitution" have been disputed. Indeed, both documents in question (US and Polish constitutions) were preceded by earlier ones,[94] including those also labelled as constitutions, e.g., the Corsican Constitution of 1755.[101] See history of the constitution.

b ^ Machnikowski uses the word Fatherland.[5] The English translation of the Constitution of May 3, 1791, by Christopher Kasparek, reproduced in Wikisource, renders "ojczyzna" as "country" (the usual English-language equivalent), e.g., at the end of section II, "The Landed Nobility". The English cognate of the Polish "ojczyzna" is "fatherland" — both words are calques of the Latin "patria," itself derived from "pater" ("father"). Some feminists might prefer "motherland."

c ^ The contemporaneous United States Constitution sanctioned the continuation of slavery. Thus neither of the two constitutions enfranchised all its adult male population: the U.S. Constitution excluded America's slaves; the Polish Constitution — Poland's peasants.

d ^ King Stanisław August himself had been elected in 1764 with the support of his ex-mistress, Russian Tsarina Catherine the Great — including bribes and a Russian army deployed only a few miles from the election sejm, meeting at Wola outside Warsaw.

References

- ^ a b Albert P. Blaustein (1993). Constitutions of the world. Wm. S. Hein Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 9780837703626. http://books.google.com/books?id=2xCMVAFyGi8C&pg=PA15. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ^ a b Bill Moyers (5 May 2009). Moyers on Democracy. Random House Digital, Inc.. p. 68. ISBN 9780307387738. http://books.google.com/books?id=f42INaX6uX8C&pg=PA68. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ^ a b Sandra Lapointe; Jan Wolenski; Mathieu Marion (2009). The Golden Age of Polish Philosophy: Kazimierz Twardowski's Philosophical Legacy. Springer. p. 4. ISBN 9789048124008. http://books.google.com/books?id=5u84tl5ux0gC&pg=PA4. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Davies, Norman (1996). Europe: A History. Oxford University Press. p. 699. ISBN 0198201710. http://books.google.com/books?id=jrVW9W9eiYMC&pg=PA699.

- ^ a b c Machnikowski (1 December 2010). Contract Law in Poland. Kluwer Law International. p. 20. ISBN 9789041133960. http://books.google.com/books?id=Iu___HYTHDkC&pg=PA20. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. p. 151. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Piotr Stefan Wandycz (2001). The price of freedom: a history of East Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the present. Psychology Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-415-25491-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=m5plR3x6jLAC&pg=PA66. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Norman Davies (30 March 2005). God's Playground: The origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9. http://books.google.com/books?id=07vm4vmWPqsC&pg=PA273. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Daniel Stone (1 September 2001). The Polish-Lithuanian state, 1386-1795. University of Washington Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-0-295-98093-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=LFgB_l4SdHAC&pg=PA98. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Daniel Stone (1 September 2001). The Polish-Lithuanian state, 1386-1795. University of Washington Press. pp. 106. ISBN 978-0-295-98093-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=LFgB_l4SdHAC&pg=PA106. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ J. K. Fedorowicz; Maria Bogucka; Henryk Samsonowicz (1982). A Republic of nobles: studies in Polish history to 1864. CUP Archive. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-521-24093-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=p7U8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA110. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Francis Ludwig Carsten (1 January 1961). The new Cambridge modern history: The ascendancy of France, 1648-88. CUP Archive. pp. 561–562. ISBN 9780521045445. http://books.google.com/books?id=FzQ9AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA562. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ a b Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. p. 156. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ (Polish) Sejm skonfederowany, WIEM Encyklopedia. Retrieved on 4 July 2011.

- ^ a b Norman Davies (30 March 2005). God's Playground: The origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9. http://books.google.com/books?id=07vm4vmWPqsC&pg=PA274. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Will Durant; Ariel Durant (1992). Rousseau and Revolution: a history of civilization in France, England and Germany from 1756, and in the remainder of Europe from 1715, to 1789. MJF Books. p. 474. ISBN 9781567310214. http://books.google.com/books?id=TNnUPQAACAAJ. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. pp. 153–154. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Piotr Stefan Wandycz (2001). The price of freedom: a history of East Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the present. Psychology Press. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-415-25491-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=m5plR3x6jLAC&pg=PA103. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b Norman Davies (20 January 1998). Europe: a history. HarperCollins. p. 659. ISBN 978-0-06-097468-8. http://books.google.com/books?id=4StZDvPCcJEC&pg=PA659. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. p. 157. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. p. 158. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b c John P. LeDonne (1997). The Russian empire and the world, 1700-1917: the geopolitics of expansion and containment. Oxford University Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 9780195109276. http://books.google.com/books?id=P6ks6FSAMacC&pg=PA41. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d Hugh Seton-Watson (1 February 1988). The Russian empire, 1801-1917. Clarendon Press. p. 44. ISBN 9780198221524. http://books.google.com/books?id=40KbWNve4XkC&pg=PA44. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Richard Butterwick (1998). Poland's last king and English culture: Stanisław August Poniatowski, 1732-1798. Clarendon Press. p. 169. ISBN 9780198207016. http://books.google.com/books?id=ySzrq3JwjBEC&pg=PA169. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa George Sanford (2002). Democratic government in Poland: constitutional politics since 1989. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9780333774755. http://books.google.com/books?id=tOaXi0hX1RAC&pg=PA11. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ a b c Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. p. 159. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Andrzej Jezierski; Cecylia Leszczyńska (2003). Historia gospodarcza Polski. Key Text Wydawnictwo. p. 68. ISBN 9788387251710. http://books.google.com/books?id=_75stIZO7WAC&pg=PP1. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ a b c Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. p. 160. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ David R. Collins; Larry Nolte (September 1995). Casimir Pulaski: soldier on horseback. Pelican Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-56554-082-8. http://books.google.com/books?id=xTXQHhj6bScC&pg=PA29. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Jerzy Lukowski; Hubert Zawadzki (2001). A concise history of Poland. Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–99. ISBN 9780521559171. http://books.google.com/books?id=NpMxTvBuWHYC&pg=PA96. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Sharon Korman (1996). The right of conquest: the acquisition of territory by force in international law and practice. Oxford University Press US. p. 75. ISBN 9780198280071. http://books.google.com/books?id=ueDO1dJyjrUC&pg=PA75. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ a b c Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. pp. 164–165. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ David Lay Williams (1 August 2007). Rousseau's Platonic Enlightenment. Penn State Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-271-02997-9. http://books.google.com/books?id=nsRrONAvdnYC&pg=PA202. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^ Matthew P. Romaniello; Charles Lipp (1 March 2011). Contested spaces of nobility in early modern Europe. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-4094-0551-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=hCgx4S51uQwC&pg=PA238. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^ Jerzy Lukowski (3 August 2010). Disorderly liberty: the political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=kAgRHvulnnUC&pg=PA124. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^ a b Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. pp. 166–167. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Maurice William Cranston (1997). The solitary self: Jean-Jacques Rousseau in exile and adversity. University of Chicago Press. p. 177. ISBN 9780226118659. http://books.google.com/books?id=zMYmGHEsD5MC&pg=PA177. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. pp. 169–171. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. p. 179. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. pp. 162–163. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Daniel Stone (1 September 2001). The Polish-Lithuanian state, 1386-1795. University of Washington Press. pp. 274–275. ISBN 978-0-295-98093-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=LFgB_l4SdHAC&pg=PA274. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^ Ted Tapper; David Palfreyman (23 December 2004). Understanding mass higher education: comparative perspectives on access. RoutledgeFalmer. p. 140. ISBN 9780415354912. http://books.google.com/books?id=riv0UCM90AMC&pg=RA2-PA140. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Norman Davies (May 2005). God's Playground: 1795 to the present. Columbia University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780231128193. http://books.google.com/books?id=EBpghdZeIwAC&pg=PA167. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Richard Butterwick (1998). Poland's last king and English culture: Stanisław August Poniatowski, 1732-1798. Clarendon Press. pp. 158–162. ISBN 9780198207016. http://books.google.com/books?id=ySzrq3JwjBEC&pg=RA1-PA158. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Janusz Justyński (1991). The Origin of human rights: the constitution of 3 May 1791, the French declaration of rights, the Bill of Rights : proceedings at the seminar held at the Nicolaus Copernicus University, May 3–5, 1991. Wydawn. Adam Marszałek. p. 171. ISBN 978-83-85263-24-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=TcKFAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ Antoni Jan Ostrowski (1873). Żywot Tomasza Ostrowskiego, ministra rzeczypospolitej póżniej,prezesa senatu xięstwa warszawskiego i królestwa polskiego: obejmujacy rys wypadḱow krajowych od 1765 roku do 1817. Nakł. K. Ostrowskiego. p. 73. http://books.google.com/books?id=Q2wRAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA73. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ^ a b c Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. p. 176. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b Robert Bideleux; Ian Jeffries (28 January 1998). A history of eastern Europe: crisis and change. Psychology Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-415-16111-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=6Eh9KQTrOckC&pg=PA160. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ a b William Young (September 2006). German Diplomatic Relations 1871-1945: The Wilhelmstrasse and the Formulation of Foreign Policy. iUniverse. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-595-40706-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=UftWq64mmyoC&pg=PA6. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ a b c Jerzy Lukowski (3 August 2010). Disorderly liberty: the political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=kAgRHvulnnUC&pg=PA226. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ (Polish) Stronnictwo Patriotyczne, Encyklopedia WIEM

- ^ Piotr Stefan Wandycz (2001). The price of freedom: a history of East Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the present. Psychology Press. p. 128. ISBN 9780415254915. http://books.google.com/books?id=m5plR3x6jLAC&pg=PA128. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ a b Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. pp. 172–173. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. pp. 173–174. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. p. 178. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. p. 175. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Włodzimierz Sochacki (2007). Historia dla maturzystów: repetytorium. Wlodzimierz Sochacki. p. 278. ISBN 978-83-60186-58-9. http://books.google.com/books?id=0kB2QlHqIXYC&pg=PA278. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ Marceli Handelsman (1907). Konstytucja trzeciego Maja r. 1791. Druk. Narodowa. pp. 50–52. http://books.google.com/books?id=rPQDAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA51. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. p. 177. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Paul W. Schroeder (1996). The transformation of European politics, 1763-1848. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 84. ISBN 9780198206545. http://books.google.com/books?id=BS2z3iGPCigC&pg=PA84. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Jerzy Lukowski; Hubert Zawadzki (2001). A concise history of Poland. Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 9780521559171. http://books.google.com/books?id=NpMxTvBuWHYC&pg=PA84. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Francis W. Carter (1994). Trade and urban development in Poland: an economic geography of Cracow, from its origins to 1795. Cambridge University Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-521-41239-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=-XdByzq85zMC&pg=PA192. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ Norman Davies (30 March 2005). God's Playground: The origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. p. 403. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9. http://books.google.com/books?id=07vm4vmWPqsC&pg=PA403. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ Hon. Carl L. Bucki (May 3, 1996). "Constitution Day: May 3, 1791". Polish Academic Information Center. http://info-poland.buffalo.edu/classroom/constitution.html. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ Robert Howard Lord (1915). The second partition of Poland: a study in diplomatic history. Harvard University Press. p. 275. http://books.google.com/books?id=zp5pAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA275. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ a b Michal Kopeček (2006). Discourses of collective identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770-1945): texts and commentaries. Central European University Press. pp. 282–284. ISBN 978-963-7326-52-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=k5Vsjg508EYC&pg=PA282. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ a b Michal Kopeček (2006). Discourses of collective identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770-1945): texts and commentaries. Central European University Press. pp. 284–285. ISBN 978-963-7326-52-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=k5Vsjg508EYC&pg=PA284. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Joseph Kasparek-Obst (1 June 1980). The constitutions of Poland and of the United States: kinships and genealogy. American Institute of Polish Culture. p. 42. ISBN 9781881284093. http://books.google.com/books?id=nu-CQgAACAAJ. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ a b Joseph Kasparek-Obst (1 June 1980). The constitutions of Poland and of the United States: kinships and genealogy. American Institute of Polish Culture. p. 40. ISBN 9781881284093. http://books.google.com/books?id=nu-CQgAACAAJ. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ Joseph Kasparek-Obst (1 June 1980). The constitutions of Poland and of the United States: kinships and genealogy. American Institute of Polish Culture. p. 51. ISBN 9781881284093. http://books.google.com/books?id=nu-CQgAACAAJ. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d Jerzy Lukowski (3 August 2010). Disorderly liberty: the political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=kAgRHvulnnUC&pg=PA226. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ Joseph Kasparek-Obst (1 June 1980). The constitutions of Poland and of the United States: kinships and genealogy. American Institute of Polish Culture. p. 31. ISBN 9781881284093. http://books.google.com/books?id=nu-CQgAACAAJ. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ Wojciech Roszkowski (1991). Landowners in Poland, 1918-1939. East European Monographs. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-88033-196-8. http://books.google.com/books?id=QUKFAAAAIAAJ. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ Hamish M. Scott (1995). The European nobilities in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Longman. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-582-08071-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=whFnAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. p. 174. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d Jerzy Lukowski (3 August 2010). Disorderly liberty: the political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=kAgRHvulnnUC&pg=PA226. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Jerzy Lukowski (3 August 2010). Disorderly liberty: the political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=kAgRHvulnnUC&pg=PA226. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Jerzy Lukowski (3 August 2010). Disorderly liberty: the political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=kAgRHvulnnUC&pg=PA226. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ Joseph Kasparek-Obst (1 June 1980). The constitutions of Poland and of the United States: kinships and genealogy. American Institute of Polish Culture. pp. 45–49. ISBN 9781881284093. http://books.google.com/books?id=nu-CQgAACAAJ. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ a b c Jerzy Lukowski (3 August 2010). Disorderly liberty: the political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=kAgRHvulnnUC&pg=PA226. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ Poland; Jerzy Kowecki (1991). Konstytucja 3 Maja 1791. Państwowe Wydawn. Nauk.. pp. 105–107. http://books.google.com/books?id=M38lAQAAIAAJ. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ Maria Konopka-Wichrowska (2003-08-13). "My, Litwa". Podkowiański Magazyn Kulturalny. http://free.art.pl/podkowa.magazyn/archiwum/my_litwa.htm. Retrieved 2011-09-12. ""Ostatnim było Zaręczenie Wzajemne Obojga Narodów przy Konstytucji 3 Maja, stanowiące część nowych paktów konwentów — zdaniem historyka prawa Bogusława Leśnodorskiego: „zacieśniające unię, ale utrzymujące nadal federacyjny charakter Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów”""

- ^ Lietuvos TSR istorija. T. 1: Nuo seniausių laikų iki 1917 metų. – 2 leid. Vilnius, 1986, p. 222. Transcript of original translation can be found on Senieji lietuviški raštai (Old Lithuanian texts), Lituanistica, Istorija.net

- ^ Joseph Kasparek-Obst (1 June 1980). The constitutions of Poland and of the United States: kinships and genealogy. American Institute of Polish Culture. pp. 45–46. ISBN 9781881284093. http://books.google.com/books?id=nu-CQgAACAAJ. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ a b Jacek Jędruch (November 1982). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493-1977: a guide to their history. University Press of America. p. 180. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jl6OAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Jeremy Black (2004). Kings, nobles and commoners: states and societies in early modern Europe, a revisionist history. I.B.Tauris. p. 59. ISBN 9781860649868. http://books.google.com/books?id=wNBZRi54cisC&pg=PA59. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ J. K. Fedorowicz; Maria Bogucka; Henryk Samsonowicz (1982). A Republic of nobles: studies in Polish history to 1864. CUP Archive. p. 252. ISBN 9780521240932. http://books.google.com/books?id=p7U8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA252. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Joseph Kasparek-Obst (1 June 1980). The constitutions of Poland and of the United States: kinships and genealogy. American Institute of Polish Culture. pp. 231–232. ISBN 9781881284093. http://books.google.com/books?id=nu-CQgAACAAJ. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e (Polish) Rafał Kowalczyk and Łukasz Kamiński, Zakazane święta PRLu, Polskie Radio Online, May 3, 2008. Retrieved on 4 July 2011 (from the Internet Archive)

- ^ a b c d John Markoff (1996). Waves of democracy: social movements and political change. Pine Forge Press. p. 121. ISBN 9780803990197. http://books.google.com/books?id=-EWi759F4PoC&pg=PA121. Retrieved 30 May 2011. "The first European country to follow the U.S. example was Poland in 1791."

- ^ Isaac Kramnick, Introduction, in James Madison; Alexander Hamilton; John Jay; Isaac Kramnick (1987). The Federalist papers. Penguin. p. 13. ISBN 9780140444957. http://books.google.com/books?id=WSzKOORzyQ4C&pg=PA13. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d (Polish) historyczny.pdf Konstytucja 3 Maja – rys historycznyPDF , University of Warsaw. Retrieved on 4 July 2011 (from the Internet Archive)

- ^ (Polish) Iwona Pogorzelska, Prezentacja na podstawie artykułu Romany Guldon „Pamiątki Konstytucji 3 Maja przechowywane w zasobie Archiwum Państwowego w Kielcach."PDF (4.14 MB) Almanach Historyczny, T. 4, Kielce 2002. Retrieved on 4 July 2011

- ^ (Polish) Rok 2007: Przegląd wydarzeń, Tygnodnik Wileńszczyzny. Retrieved on 4 July 2011

- ^ a b Polish Constitution Day - Chicago 2011 - Mayor Daley's Last Parade, Polonia Music. Retrieved on 4 July 2011.

- ^ Thousands Attend Polish Constitution Day Parade. CBS. May 7, 2011. Retrieved on 4 July 2011

- ^ Carrington, Dorothy (07 1973). "The Corsican constitution of Pasquale Paoli (1755–1769)". The English Historical Review 88' (348): 48. JSTOR 564654

Further reading

- Jerzy Kowecki, ed., Konstytucja 3 maja 1791 (The Constitution of May 3, 1791), przedmową opatrzył (with foreword by) Bogusław Leśnodorski, Warsaw, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1981, ISBN 83-01-01915-8.

- Polska Akademia Nauk – Biblioteka Kórnicka (Polish Academy of Sciences, Kórnik Library), Ustawodawstwo Sejmu Wielkiego z 1791 r. (Legislation of the Great Sejm of 1791), Kórnik, 1985. Compilation of facsimile reprints of 1791 legislation pertinent to the Constitution of May 3, 1791.

- Hillar, Marian (1992). "The Polish Constitution of May 3, 1791: Myth and Reality". The Polish Review XXXVII (2): 185–207.

- Adam Zamoyski, The Polish Way: a Thousand-Year History of the Poles and Their Culture, New York, Hippocrene Books, 1994.

- Jacek Jędruch, Constitutions, Elections and Legislatures of Poland, 1493–1993, Summit, NJ, EJJ Books, 1998, ISBN 0-7818-0637-2.

- Norman Davies, God's Playground, 2 vols., ISBN 0-231-05353-3 and ISBN 0-231-05351-7.

- Paweł Jasienica, Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów (The Commonwealth of the Two Nations), ISBN 83-06-01093-0.

- Emanuel Rostworowski, Maj 1791 – maj 1792: rok monarchii konstytucyjnej (May 1791 – May 1792: the Year of Constitutional Monarchy), Warsaw, Zamek Królewski (Royal Castle), 1985.

- Hugo Kołłątaj and Ignacy Potocki, On the Adoption and Fall of the Polish May 3 Constitution, Leipzig, 1793.

External links

- Polishconstitution.org: Site about the May 3 Constitution that includes a partial English translation by Christopher Kasparek.

- History of Polish law until 1795.

- The Constitution of May 3, 1791, by Hon. Carl L. Bucki.

- Constitutions, Elections and Legislatures of Poland, 1493–1993. Jacek Jędruch. Chapter Two MONARCHY BECOMES THE FIRST REPUBLIC: KINGS ELECTED FOR LIFE

- Commonwealth of Diverse Cultures: Poland's Heritage

Acts of the Polish–Lithuanian union (1385–1569) Krewo (1385) · Vilnius and Radom (1401) · Horodło (1413) · Grodno (1432) · Kraków and Vilna (1499) · Mielnik (1501) · Lublin (1569)

See also: 3 May 1791 Constitution (Reciprocal Guarantee of Two Nations)Categories:- 1791 in law

- 1791 in Poland

- 1791 in Lithuania

- Polish–Lithuanian union

- History of Lithuania (1569–1795)

- History of Poland (1569–1795)

- History of Belarus (1569–1795)

- Constitutions of Poland

- Constitutions of former countries

- Great Sejm

- Legal history of Poland

- Legal history of Lithuania

- Age of Enlightenment

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.