- Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire

-

Coordinates: 40°43′48″N 73°59′43″W / 40.730085°N 73.995356°W

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire

Date March 25, 1911 Time 4:40 PM (local time) Location Manhattan, New York City, U.S. Casualties 146 dead 71 injured The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City on March 25, 1911, was the deadliest industrial disaster in the history of the city of New York and resulted in the fourth highest loss of life from an industrial accident in U.S. history. It was also the second deadliest disaster in New York City – after the burning of the General Slocum on June 15, 1904 – until the destruction of the World Trade Center 90 years later. The fire caused the deaths of 146 garment workers, who died from the fire, smoke inhalation, or falling to their deaths. Most of the victims were recent Jewish and Italian immigrant women aged sixteen to twenty-three;[1][2][3] the oldest victim was 48, the youngest were two fourteen-year-old girls.[4] Because the managers had locked the doors to the stairwells and exits, many of the workers who could not escape the burning building jumped from the eighth, ninth, and tenth floors to the streets below. The fire led to legislation requiring improved factory safety standards and helped spur the growth of the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union, which fought for better working conditions for sweatshop workers.

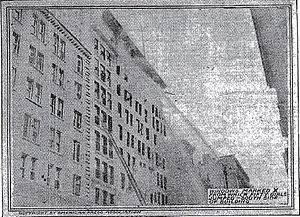

The factory was located in the Asch Building, at 23-29 Washington Place, now known as the Brown Building, which has been designated a National Historic Landmark and a New York City landmark.[5]

Contents

Fire

The Triangle Waist Company[6] factory occupied the eighth, ninth, and tenth floors of the 10-story Asch Building on the northwest corner of Greene Street and Washington Place, just east of Washington Square Park, in the Greenwich Village area of New York City. Under the ownership of Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, the factory produced women's blouses, known as "shirtwaists." The factory normally employed about 500 workers, mostly young immigrant women, who worked nine hours a day on weekdays plus seven hours on Saturdays.[7]

As the workday was ending on the afternoon of Saturday, March 25, 1911, a fire flared up at approximately 4:40 PM in a scrap bin under one of the cutter's tables at the northeast corner of the eighth floor.[8] The first fire alarm was sent at 4:45 PM by a passerby on Washington Place who saw smoke coming from the eighth floor.[9] Both owners of the factory were in attendance and had invited their children to the factory on that afternoon.[10] The Fire Marshal concluded that the likely cause of the fire was the disposal of an unextinguished match or cigarette butt in the scrap bin, which held two months' worth of accumulated cuttings by the time of the fire.[11] Although smoking was banned in the factory, cutters were known to sneak cigarettes, exhaling the smoke through their lapels to avoid detection.[12] A New York Times article suggested that the fire may have been started by the engines running the sewing machines, while The Insurance Monitor, a leading industry journal, suggested that the epidemic of fires among shirtwaist manufacturers was "fairly saturated with moral hazard."[10] No one suggested arson.

A bookkeeper on the eighth floor was able to warn employees on the tenth floor via telephone, but there was no audible alarm and no way to contact staff on the ninth floor.[13] According to survivor Yetta Lubitz, the first warning of the fire on the ninth floor arrived at the same time as the fire itself.[14] Although the floor had a number of exits – two freight elevators, a fire escape, and stairways down to Greene Street and Washington Place – flames prevented workers from descending the Greene Street stairway, and the door to the Washington Place stairway was locked to prevent theft by the workers; the locked doors allowed managers to check the women's purses.[15] The foreman who held the stairway door key had already escaped by another route.[16] Dozens of employees escaped the fire by going up the Greene Street stairway to the roof. Other survivors were able to jam themselves into the elevators while they continued to operate.

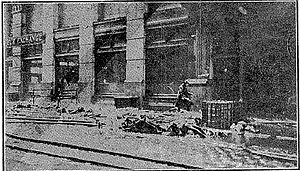

Within three minutes, the Greene Street stairway became unusable in both directions.[17] Terrified employees crowded onto the single exterior fire escape, a flimsy and poorly-anchored iron structure which may have been broken before the fire. It soon twisted and collapsed from the heat and overload, spilling victims nearly 100 feet (30 m) to their deaths on the concrete pavement below. Elevator operators Joseph Zito[18] and Gaspar Mortillalo saved many lives by traveling three times up to the ninth floor for passengers, but Mortillalo was eventually forced to give up when the rails of his elevator buckled under the heat. Some victims pried the elevator doors open and jumped into the empty shaft, trying to slide down the cables or to land on top of the car. The weight and impacts of these bodies warped the elevator car and made it impossible for Zito to make another attempt.

A large crowd of bystanders gathered on the street, witnessing sixty-two people jumping or falling to their deaths from the burning building.[19] Louis Waldman, later a New York Socialist state assemblyman, described the scene years later:[20]

One Saturday afternoon in March of that year — March 25, to be precise — I was sitting at one of the reading tables in the old Astor Library... It was a raw, unpleasant day and the comfortable reading room seemed a delightful place to spend the remaining few hours until the library closed. I was deeply engrossed in my book when I became aware of fire engines racing past the building. By this time I was sufficiently Americanized to be fascinated by the sound of fire engines. Along with several others in the library, I ran out to see what was happening, and followed crowds of people to the scene of the fire.A few blocks away, the Asch Building at the corner of Washington Place and Greene Street was ablaze. When we arrived at the scene, the police had thrown up a cordon around the area and the firemen were helplessly fighting the blaze. The eighth, ninth, and tenth stories of the building were now an enormous roaring cornice of flames.

Word had spread through the East Side, by some magic of terror, that the plant of the Triangle Waist Company was on fire and that several hundred workers were trapped. Horrified and helpless, the crowds — I among them — looked up at the burning building, saw girl after girl appear at the reddened windows, pause for a terrified moment, and then leap to the pavement below, to land as mangled, bloody pulp. This went on for what seemed a ghastly eternity. Occasionally a girl who had hesitated too long was licked by pursuing flames and, screaming with clothing and hair ablaze, plunged like a living torch to the street. Life nets held by the firemen were torn by the impact of the falling bodies.

The emotions of the crowd were indescribable. Women were hysterical, scores fainted; men wept as, in paroxysms of frenzy, they hurled themselves against the police lines.The remainder waited until smoke and fire overcame them. The fire department arrived quickly but was unable to stop the flames, as there were no ladders available that could reach beyond the sixth floor. The fallen bodies and falling victims also made it difficult for the fire department to approach the building.

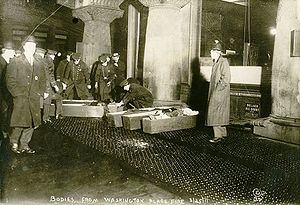

Aftermath

Although early references of the death toll ranged from 141[21] to 148,[22] almost all modern references agree that 146 people died as a result of the fire; 129 women and 17 men.[23][24][25][26][27][28][29] Six victims remained unidentified until 2011.[23][24] Most victims died of burns, asphyxiation, blunt impact injuries, or a combination of the three.[30]

The first person to jump was a man, and another man was seen kissing a young woman at the window before they both jumped to their deaths.[31]

Twenty-two victims of the fire were buried by the Hebrew Free Burial Association in a special section at Mount Richmond Cemetery. In some instances, their tombstones refer to the fire.[32] The six victims who remained unidentified were buried together in the Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn. Originally interred elsewhere on the grounds, their remains now lie underneath a monument to the tragedy: a large marble slab featuring a kneeling woman.[33] The six unknown victims were finally identified in February 2011[23] and a grave marker placed in their memory[34]

Consequences

The company's owners, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, who survived the fire by fleeing to the building's roof when the fire began, were indicted on charges of first and second degree manslaughter in mid-April; the pair's trial began on December 4, 1911.[35] Max Steuer, counsel for the defendants, managed to destroy the credibility of one of the survivors, Kate Alterman, by asking her to repeat her testimony a number of times — which she did without altering key phrases. Steuer argued to the jury that Alterman and possibly other witnesses had memorized their statements, and might even have been told what to say by the prosecutors. The defense also stressed that the prosecution had failed to prove that the owners knew the exit doors were locked at the time in question. The jury acquitted the two men, but they lost a subsequent civil suit in 1913 in which plaintiffs won compensation in the amount of $75 per deceased victim. The insurance company paid Blanck and Harris about $60,000 more than the reported losses, or about $400 per casualty. In 1913, Blanck was once again arrested for locking the door in his factory during working hours. He was fined $20.[36]

Tombstone of fire victim at the Hebrew Free Burial Association's Mount Richmond Cemetery

Tombstone of fire victim at the Hebrew Free Burial Association's Mount Richmond Cemetery

Rose Schneiderman, a prominent socialist and union activist, gave a speech at the memorial meeting held in the Metropolitan Opera House on April 2, 1911, to an audience largely made up of the members of the Women's Trade Union League. She used the fire as an argument for factory workers to organize:

I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public and we have found you wanting. ... We have tried you citizens; we are trying you now, and you have a couple of dollars for the sorrowing mothers, brothers and sisters by way of a charity gift. But every time the workers come out in the only way they know to protest against conditions which are unbearable the strong hand of the law is allowed to press down heavily upon us.

Public officials have only words of warning to us—warning that we must be intensely peaceable, and they have the workhouse just back of all their warnings. The strong hand of the law beats us back, when we rise, into the conditions that make life unbearable.

I can't talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled. I know from my experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.[37]

Others in the community, and in particular in the ILGWU,[38] drew a different lesson from events. The New York State Legislature created its New York State Factory Investigating Committee to "investigate factory conditions in this and other cities and to report remedial measures of legislation to prevent hazard or loss of life among employees through fire, unsanitary conditions, and occupational diseases."[39] New York City's Fire Chief John Kenlon told the investigators that his department had identified more than 200 factories where conditions made a fire like that at the Triangle Factory possible.[40] The State Committee's 1915 report helped modernize the state's labor laws. It made New York State "one of the most progressive states in terms of labor reform."[41][42] As a result of the fire, the American Society of Safety Engineers was founded in New York City on October 14, 1911.[43]

Hilda Solis, the American Secretary of Labor, seen on the overhead screen, speaking at the Centennial Memorial; the Brown (Asch) Building is on the far right

Hilda Solis, the American Secretary of Labor, seen on the overhead screen, speaking at the Centennial Memorial; the Brown (Asch) Building is on the far right

Centennial

A coalition of preservation organizations, historians, artists, and labor activists, including the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, the Gotham Center, the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, the Bowery Poetry Club and others, came together to form the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition,[44] whose goal was to commemorate the centennial of the fire, which took place on March 25, 2011.

The ceremony was preceded by a march through Greenwich Village by thousands of people, some carrying shirtwaists – women's blouses – on poles, or wearing sashes commemorating the names of those who died in the fire. Speakers at the memorial included New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who received a mixed response, and U.S. Secretary of Labor Hilda Solis.[45]

In popular culture

- Films and television

- With These Hands (1950), directed by Jack Arnold[46]

- The Triangle Factory Fire Scandal (1979), directed by Mel Stuart, produced by Mel Brez and Ethel Brez[47]

- Those Who Know Don't Tell: The Ongoing Battle for Workers' Health (1990), produced by Abby Ginzberg, narrated by Studs Terkel[48]

- The Living Century: Three Miracles (2001) premiered on PBS, focusing on the life of 107-year old Rose Freedman (died 2002), who became the last living survivor of the fire.

- American Experience: Triangle Fire (2011), documentary produced and directed by Jamila Wignot, narrated by Michael Murphy[49]

- Triangle Remembering the Fire (2011) premiered on HBO on March 21, four days short of the 100th anniversary.

- Music

- "My Little Shirtwaist Fire" by Rasputina, from their 1996 album Thanks for the Ether.

- Theatre

- In Ain Gordon's play Birdseed Bundles (2000), the Triangle Fire is a major dramatic engine of the story.[50]

- The Triangle Factory Fire Project, a play written by Christopher Piehler about the fire and the trial afterward.

- The musical Rags – book by Joseph Stein, lyrics by Stephen Schwartz, and music by Charles Strouse – incorporates the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in the second act.

- Literature

- Margaret Peterson Haddix's 2007 historical novel for young adults, Uprising, deals with immigration, women's rights, and the labor movement, with the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire as a central element.

- Esther Friesner's Threads and Flames deals with a young girl, named Raisa, who works at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory at the time of the fire.

- Mary Jane Auch's 2004 historical novel for young adults, Ashes of Roses tells the tale of Margaret Rose Nolan, a young girl who works at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory at the time of the fire, along with her sister and her friends.

See also

- American Society of Safety Engineers

- International Ladies' Garment Workers Union

- International Women's Day

- New York City Fire Department

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition

- Rhinelander Waldo, N.Y.C. Fire Commissioner in 1911

References

- Notes

- ^ "Triangle Shirtwaist Fire". Jewish Women: An Historical Encyclopedia on Jewish Women's Archive

- ^ Stacy, Greg. "Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Marks a Sad Centennial". NPR.org via Online Journal (March 24, 2011)

- ^ Diner, Hasia R. "Lecture: The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire and the Shared Italian-Jewish History of New York" Italian-American Magazine (March 16, 2011)

- ^ "List of Victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire". Famous Trials. http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/triangle/trianglevictims2.html. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ NYC Landmark

- ^ "Complete Transcript of Triangle Fire". Cornell University ILR School DigitalCommons@ILR. 11-1-1911. p. 22. http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1017&context=triangletrans. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ von Drehl, p. 105

- ^ von Drehle, p. 118.

- ^ Stein, p. 224

- ^ a b von Drehle, p. 163

- ^ Stein p.33

- ^ von Drehle, 119

- ^ von Drehle, 131

- ^ von Drehle, 141–2

- ^ Lange, Brenda. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, Infobase Publishing, 2008, page 58

- ^ PBS: "Introduction: Triangle Fire", accessed March 1, 2011

- ^ von Drehle, 143–4

- ^ von Drehle, 157

- ^ Shepherd, William G. (1911-03-27). "Eyewitness at the Triangle". http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/trianglefire/texts/stein_ootss/ootss_wgs.html?location=Fire!. Retrieved 2007-09-02

- ^ Waldman, Labor Lawyer, E.P. Dutton & Co., pp. 32–33.

- ^ "141 Men and Girls Die in Waist Factory Fire". The New York Times, March 26, 1911. Accessed December 20, 2009.

- ^ "New York Fire Kills 148: Girl Victims Leap to Death from Factory" (reprint). Chicago Sunday Tribune. 1911-03-26. p. 1. http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/trianglefire/texts/newspaper/cst_032611.html?location=Fire!. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ^ a b c Berger, Joseph (February 20, 2011). "100 Years Later, the Roll of the Dead in a Factory Fire Is Complete". February 20, 2011 (New York Times). http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/21/nyregion/21triangle.html. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ a b von Drehle, passim

- ^ "In Memoriam: The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire." The New York Times, March 26, 1997.

- ^ "The Triangle Factory Fire". The Kheel Center, Cornell University.

- ^ "98th Anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire". New York City Fire Department.

- ^ "Labor Department Remembers 95th Anniversary of Sweatshop Fire". U.S. Department of Labor.

- ^ Stein, passim

- ^ von Drehle, 271–83

- ^ von Drehle, 155–7

- ^ "HFBA Timeline". http://hebrewfreeburial.org/timeline.html. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ "Evergreens Cemetery". http://www.theevergreenscemetery.com/stories/shirtwaist-fire/the-triangle-shirtwaist-fire. Retrieved 2009-05-28. Evergreens Cemetery reports that there were originally eight burials, one male and six females, along with some unidentified remains. One of the female victims was later identified and her body removed to another cemetery. Other accounts do not mention the unidentified remains at all. Rose Freedman was the last living survivor of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire.(1893–2001)

- ^ A Grave Marker Unveiled for Six Triangle Fire Victims Who Had Been Unknowns Jewish Daily Forward April 8, 2011.

- ^ Stein p.158

- ^ Hoenig, John M. "The Triangle Fire of 1911", History Magazine, April/May 2005.

- ^ Schneiderman, Rose. "We Have Found You Wanting" (reprint). http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/trianglefire/primary/testimonials/ootss_RoseSchneiderman.html.

- ^ Jones, Gerard (2005). Men of Tomorrow. NY: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-03657-0.

- ^ New York Times': "Seek Way to Lessen Factory Dangers," October 11, 1911, accessed February 8, 2011

- ^ New York Times: "Factory Firetraps Found by Hundreds," October 14, 1911, accessed February 8, 2011

- ^ Greenwald, Richard A. The Triangle Fire, the Protocols of Peace, and Industrial Democracy in Progressive Era New York (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2005), 128

- ^ The Economist, "Triangle Shirtwaist: The birth of the New Deal", 19 March 2011, p. 39.

- ^ American Society of Safety Engineers (2001). "A Brief History of the American Society of Safety Engineers: A Century of Safety". http://www.asse.org/about/history.php. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition website.

- ^ Safronova, Valeriya and Hirshon, Nicholas. "Remembering tragic 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist inferno, marchers flood Greenwich Village streets" New York Daily News (March 26, 2011)

- ^ Internet Movie Database: With These Hands (1950), accessed February 18, 2011

- ^ "Triangle Factory Fire Scandal (TV 1979)". http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0080048/. Retrieved 2011-02-18.

- ^ "Those Who Know Don't Tell". http://www.filmakers.com/index.php?a=filmDetail&filmID=323. Retrieved 2011-02-18.

- ^ "Triangle Fire". http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/triangle/. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- ^ Lefkowitz, David. "OOB's DTW Runs Out of Birdseed, April 2". Playbill.com

- Bibliography

- Stein, Leon (1962). The Triangle Fire. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8714-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=zMu0zgnfNAUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=the+triangle+fire#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- von Drehle, David (2003). Triangle: The Fire That Changed America. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-874-3.

- Further reading

- Auch, Mary Jane (2002). Ashes of Roses. Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 0-8050-6686-1.

- Chernoff, Alan. "Remembering the Triangle Fire 100 years later". CNN/Money (March 25, 2011)

- Haddix, Margaret Peterson (2007). Uprising. Simon & Schuster Children's Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4169-1171-5.

- Sosinsky, Leigh (2011). The New York City Triangle Factory Fire. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-7403-5

- Weber, Katharine (2007). Triangle. Picador. ISBN 978-0-374-28142-7.

External links

- General

- Contemporaneous accounts

- "Eyewitness at the Triangle"

- 1911 McClure Magazine article (see pages 455–483)

- Trial

- Complete Transcript Of Triangle Trial: People Vs. Isaac Harris and Max Blanck

- "Famous Trials: The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Trial"

- 1912 New York Court record (see pages 48–50)

- Articles

- "Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Building", National Park Service

- "Remembering the Triangle Fire", Jewish Daily Forward

- "The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire: The fire that changed America", Failure magazine

- Memorials and centennial

- Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition 1911–2011

- Conference: "Out of the Smoke and the Flame: The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire and its Legacy"

- CHALK: annual community commemoration

Categories:- 1911 disasters

- 1911 fires

- 1911 in New York

- Building fires in New York City

- Fire disasters involving barricaded escape routes

- History of labor relations in the United States

- Industrial accidents and incidents

- Industrial fires

- Progressive Era in the United States

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.