- Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead

Infobox Play

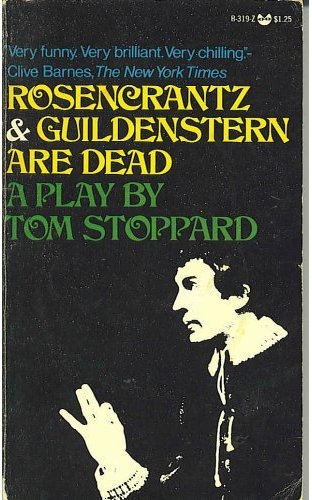

name = Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead

image_size = 150px

caption = Grove Press, 1968 edition

writer =Tom Stoppard

characters = Rosencrantz

Guildenstern

The Player

Hamlet

Tragedians

King Claudius

Gertrude

Polonius

Ophelia

Horatio

Fortinbras

Soldiers, courtiers, and musicians

setting = Shakespeare's Hamlet

premiere =26 August 1966

place =Edinburgh Fringe Edinburgh ,Scotland

orig_lang = English

subject =

genre = Tragic comedy

web =

playbill =

ibdb_id = 7644"Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead" is an absurdist, existentialist

tragicomedy byTom Stoppard , first staged at theEdinburgh Festival Fringe in1966 .cite web | author= Michael H. Hutchins | title=A Tom Stoppard Bibliography: Chronology | work=The Stephen Sondheim Reference Guide | url=http://www.sondheimguide.com/Stoppard/chronology.html | date=14 August 2006 | accessdate=2008-06-23] The play expands upon the exploits of two minor characters from Shakespeare's "Hamlet ".ources

The main source of "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern" is Shakespeare's "

Hamlet ". Comparisons have also been drawn toSamuel Beckett 's "Waiting For Godot ", for the presence of two central characters who almost appear to be two halves of a single character. Many plot features are similar as well: the characters pass time by playing Questions, impersonating other characters, and interrupting each other or remaining silent for long periods of time.The title is taken directly from a passage by an ambassador in the final scene of "Hamlet" that is quoted in "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern."

The play was performed by the Royal National Theatre at London's

Old Vic Theatre on11 April 1967 . It was directed by Derek Goldby and designed by Desmond Heeley.cite web | author=Michael Berry | title=Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead | url=http://www.sff.net/people/mberry/rosen.htp| publisher=Michael Berry's Web Pages | date=24 May 2004 | accessdate=2008-06-23]Characters

*

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern : a pair of servants and childhood friends of Hamlet

* The Player: a traveling actor

* Hamlet: the Prince of Denmark

* Tragedians: traveling with the Player, including Alfred

*King Claudius : the King of Denmark, Hamlet's uncle and stepfather

* Gertrude: the Queen of Denmark, and Hamlet's mother

*Polonius : Claudius' chief adviser

*Ophelia : Polonius' daughter

*Horatio : a friend of Hamlet

*Fortinbras : the nephew of the King of Norway

* Soldiers, courtiers, and musiciansynopsis

The play concerns the misadventures and musings of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, two minor characters from William Shakespeare's "Hamlet" who are childhood friends of the Prince, focusing on their actions with the events of "Hamlet" as background. "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead" is structured as the inverse of "Hamlet"; the title characters are the leads, not supporting players, and Hamlet himself has only a small part. The duo appears on stage here when they are off-stage in Shakespeare's play, with the exception of a few short scenes in which the dramatic events of both plays coincide. In "Hamlet", Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are used by the King in an attempt to discover Hamlet's motives and to plot against him. Hamlet, however, mocks them derisively and outwits them, so that they, rather than he, are killed in the end. Thus, from Rosencrantz's and Guildenstern's perspective, the action in "Hamlet" is largely nonsensically comical.

The two characters, brought into being within the puzzling universe of Stoppard's play by an act of the playwright's creation, often confuse their names, as they have generally interchangeable, yet periodically unique, identities. They are portrayed as two clowns or fools in a world that is beyond their understanding; they cannot identify any reliable feature or the significance in words or events. Their own memories are not reliable or complete and they misunderstand each other as they stumble through philosophical arguments while not realizing the implications to themselves. They often state deep philosophical truths during their nonsensical ramblings, yet they depart from these ideas as quickly as they come to them. At times Guildenstern appears to be more enlightened than Rosencrantz; at times both of them appear to be equally confounded by the events occurring around them.

After the two characters witness a performance of "The Murder of Gonzago" - the

story within a story in the play "Hamlet" - they find themselves on a boat taking prince Hamlet to England with the troupe that staged the performance. During the voyage, they are ambushed by pirates and lose their prisoner, Hamlet, before resigning themselves to their fate. By the end of the play, the title characters have learned that they are not truly free; they cannot deviate from the life set out for them in Shakespeare's script.Major themes of the play include

existentialism ,free will vs.determinism , the search for value, and the impossibility of certainty. As with many of Tom Stoppard's works, the play has a love for cleverness and language. It treats language as a confounding system fraught with ambiguity.Summary

Act One

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern find themselves in a world that they cannot understand. The play opens with the two men betting on

coin flip s. Rosencrantz bets heads every time and wins ninety-two flips in a row. Guildenstern contemplates the meaning of the law of probability and attempts to understand logically how this situation could occur. Rosencrantz appears simpler, Guildenstern more philosophical and pensive. He cannot come to a conclusion about the coin-flipping. The reader learns why they are where they are: the king has sent for them. Guildenstern theorizes on the nature of reality, focusing on how an event becomes increasingly real as more people witness it.The Tragedians arrive. The Player inquires of the two men if they would like a show. Guildenstern and the Player cannot decide whether chance or fate have brought them together. The Player reveals that the troupe has not had much acting work of late and have actually become more like prostitutes than actors. Rosencrantz is intrigued, Guildenstern appalled. Guildenstern scares the Tragedians off when he asks them to perform a real play.

The next part of the scene comes directly from Shakespeare's

Hamlet . The Danish king and queen, Claudius and Gertrude, ask Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to discover the nature of Hamlet's recent madness.Rosencrantz is offended by the royal couple's inability to tell the difference between him and Guildenstern. While Guildenstern consoles him, Rosencrantz laments his own inability to separate his identity from that of his friend. He desires consistency, a quality lacking in the world in which he lives. The pair then engages in a ridiculous game of questions. When Hamlet runs across the stage, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern remember what they are there to do. Guildenstern proposes that Rosencrantz pretend he is Hamlet and ask him questions. Rosencrantz fails to understand the concept at first, which enrages Guildenstern, who resigns himself to the ineptness of his partner. Eventually, they actually manage to enact the role play, but they glean no new information from it. The act closes with another scene from

Hamlet in which Rosencrantz and Guildenstern finally meet Hamlet face to face.Act Two

The act opens with the end of the conversation between Rosencrantz, Guildenstern, and Hamlet. Guildenstern tries to look on the bright side, while Rosencrantz makes it clear that the pair had made no progress, that Hamlet had entirely outwitted them. The title characters enter into a comic discussion on which way the wind is blowing because Hamlet has metaphorically declared that he is mad only when the wind blows in a certain direction. Guildenstern speaks in abstractions, while Rosencrantz offers a pragmatic method of solving their problem. Guildenstern remarks on the nature of order, how every event is set off by some preceding event, and how to act at random would shatter this order.

The Player returns to the stage. He is angry that the pair had not earlier stayed to watch their play because, without an audience, his Tragedians are nothing. The Player is rather harsh, telling Rosencrantz and Guildenstern that uncertainty is the natural state of living and that they should get used to it. He tells them to stop questioning their existence because, upon examination, life appears too chaotic to comprehend. The Player, Rosencrantz, and Guildenstern lose themselves in yet another illogical conversation that demonstrates the limits of language. The Player leaves in order to prepare for his production of the "Murder of Gonzago," set to be put on in front of Hamlet and the king and queen.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are left alone again. Rosencrantz begins to ponder what actually happens when someone dies, whether a corpse feels anything inside a coffin, and the positives and negatives of spending time in a coffin. While he looks at important issues about man's helplessness in front of death and eternity, he appears ridiculous in his discourse. While Guildenstern is at first angered by his partner's ramblings, he eventually agrees with Rosencrantz's fear of death and eternity.

The royal couple enters and asks about the duo's encounter with Hamlet. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern inform them about Hamlet's interest in the Tragedians' production. After the king and queen leave, the partners contemplate their job. They see Hamlet walk by but fail to seize the opportunity to interview him. In an incident of physical comedy, Rosencrantz puts his hands over the eyes of whom he perceives to be the queen and shouts, "Guess who?" It turns out to be the boy Alfred, a member of the Tragedians. The Player reenters.

The Tragedians perform their dress rehearsal. The Player speaks about how, as actors, they do what is written. They have no choice in how their lives unfold. The play moves beyond the scope of what the reader sees in

Hamlet ; the Tragedians predict the deaths of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern at the hands of the English courtiers. Rosencrantz doesn't quite make the connection, but Guildenstern is frightened into a verbal attack on the Tragedians' inability to capture the real essence of death. The stage becomes dark.When the stage is once again visible, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern lie in the same position as had the actors portraying their deaths. The partners are upset that they have become the pawns of the royal couple. Claudius enters again and tells them to find where Hamlet has hidden Polonius' corpse. The pair bumbles about, walking in opposite directions and discussing all the possible ways of going about their duty; their conversation focuses again on probability and on how it is impossible to determine exactly what will happen next. They set a trap for Hamlet by tying their belts together, but Hamlet unwittingly avoids it. They eventually find Hamlet and try to bring him to Claudius. He leaves while the pair is bowing in the direction they believe Claudius is entering. When he enters from behind, they look ridiculous. Hamlet comes back on stage and leaves with Claudius.

Rosencrantz is delighted to find that his mission is complete, but Guildenstern knows it is not over. Hamlet enters, speaking with a Norwegian soldier. Rosencrantz decides that he is happy to accompany Hamlet to England because it means freedom from the orders of the Danish court. Guildenstern understands that wherever they go, they are still trapped in this world. The act ends here.

Act Three

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern find themselves on a ship that has already set sail. The audience is led to believe that the pair has no knowledge of how they got there. At first, they try to determine whether they are still alive. Eventually, they recognize that they are not dead and are on board a boat. They engage in some witty wordplay about in which direction they are headed and about whether it is night or day. Guildenstern comments on his interest in boats, which he likes because they are always on a certain path and he does not need to make any decisions.

They notice Hamlet and contemplate what their next step should be. Guildenstern becomes distraught because of their uncertainty. To make him feel better, Rosencrantz pretends to put a coin in both of his fists and asks Guildenstern to choose which fist has the coin. He puts coins in both hands, so that Guildenstern will win every time: an equally ridiculous but opposite outcome to the outcome of the game at the beginning of the play. Guildenstern gets angry at Rosencrantz for his lack of original thought, but then begins to comfort him when he sees that he has hurt Rosencrantz's feelings.

The duo remembers that Claudius had given them a letter. After some brief confusion over who actually has the letter, they find it. Rosencrantz mentions how he does not actually believe in England, that he does not expect them ever to arrive. They pretend to arrive at the English court and end up opening the letter. They realize that Claudius has asked for Hamlet to be killed. While Rosencrantz seems hesitant to follow their orders now, Guildenstern convinces him that they are not worthy of interfering with fate and with the plans of kings. The stage becomes black and, presumably, the characters go to sleep. Hamlet switches the letter with one he has written himself.

The pair wakes up to the faint sound of music. Eventually, they discover that the Tragedians are hidden in several barrels on deck. They are fleeing Denmark, because their play has offended Claudius. The Player tries to help Rosencrantz and Guildenstern determine from which malady Hamlet is suffering. In the midst of their contemplation, pirates attack. Hamlet, Rosencrantz, and Guildenstern and the Player all hide in separate barrels. The lights dim.

When the lights come on again, only the title characters' and the Player's barrels remain. Guildenstern is devastated by Hamlet's disappearance; he is so distraught that he has trouble putting his feelings into words. He feels as if he has no purpose without Hamlet. Guildenstern cannot contain his emotions. He shouts at Rosencrantz, who is simply trying to make him feel better. In a moment of rage, he snatches the letter and reads it again, discovering that it now calls for Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to be put to death. Guildenstern cannot understand why he and Rosencrantz are so important as to necessitate their executions.

The Player tells Guildenstern that all paths end in death. Guildenstern snaps and draws the Player's dagger from his belt, shouting at him that his portrayals of death do not do justice to the real thing. He stabs the Player and the Player appears to die. Guildenstern honestly believes he has killed the Player. Seconds later, the Tragedians begin to clap and the Player stands up and brushes himself off.

The Player tells Rosencrantz and Guildenstern that they believed his performance because they expected it. The Tragedians then act out the deaths from the final scene of "Hamlet". Guildenstern still puts up a weak defense, claiming that death is the absence of presence and no one can truly represent it.

The lighting shifts so that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are the only ones visible. Rosencrantz still does not understand why they must die. Still, he resigns himself to his fate and his character disappears. Guildenstern wonders when he passed the point where he could have stopped the series of events that has brought him to this point. He disappears as well.

The final scene features the last few lines from Shakespeare's Hamlet. The Ambassador from England announces that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead.

Themes

;Absurdity: The story underlines the irrationality of the world in multiple instances. Stoppard emphasizes the randomness of the world. In the beginning of Act One, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern bet on coin flips and Rosencrantz wins with heads ninety-two times in a row. Guildenstern creates a series of syllogisms in order to interpret this phenomenon, but nothing truly coincides with the law of probability. The impossible becomes possible through exploiting the minimal chance of a coin flip turning up heads ninety-two times in a row. The action is absurd, but possible. This incident demonstrates the absurdity of humans basing many of their actions on the probability or likelihood of an event to happen. The random appearances of the other characters, which often confuses the title characters, contributes to the same idea.cite web | author=Garrett Ziegler | title=Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead: Themes, Motifs & Symbols | url=http://www.sparknotes.com/lit/rosencrantz/themes.html | work=SparkNotes | date=2008 | accessdate=2008-06-23]

;Art vs. Reality: The players help demonstrate the conflict between art and reality. The world in which Rosencrantz and Guildenstern live lacks order. However, art allows people that live in this world, as Stoppard hints that we do, to find order. As the player king says, "There's a design at work in all art." Art and the real world are in conflict. The player king is overjoyed to find Rosencrantz and Guildenstern because his art, his control, is nothing without an audience. Yet this art angers Guildenstern to the point where he strikes the player king because this theater makes it seem as if there are definite answers to all of Guildenstern's philosophical questions. Of course, there are no answers in reality. In order to reach out to the only reality he can be sure of, Guildenstern exclaims, "No one gets up after death-there is no applause-there is only silence and some second-hand clothes, and that's death." The tension created by this theme is that the audience is watching or reading a play; the author comments on the ultimate lack of order in the world by presenting the audience with an ordered medium. [cite web | author=Ian Johnston| title=Lecture on Stoppard, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead | url=http://www.mala.bc.ca/~Johnstoi/introser/stoppard.htm | work=Johnstonia | date=10 April 1997 | accessdate=2008-06-23] Stoppard also uses his characters to comment on the believability of theater. While Guildenstern criticizes the Player for his portrayal of death, he believes the Player's performance when Guildenstern thinks he has stabbed him with a knife. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern believe exactly what the actors want them to believe. However, Stoppard complicates the idea that people believe what they expect because he never shows the deaths of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. The reader expects this event to come, but it never does. By extension, the reader should not believe that the pair dies; the reader is expected to accept that they are literary figures that live on today.

Limits of Language: Some of the conversations in the play indicate the author's belief that language places a limit on what people can express. The characters must confine their feelings within the boundaries of words. Stoppard mocks language in sequences where the characters fail to express what they are thinking because words cannot exactly capture their thoughts. Instead, they appear ridiculous.

Insignificance: Rosencrantz and Guildenstern often feel as if they are unable to make any choices that will actually have an impact on their lives. They acknowledge that they must act at the random whims of the other characters, but do not make any effort to fight this lack of control. Stoppard manifests this theme in his transition between themes. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern do not choose to move from setting to setting, but they appear in a new place without deciding to go there. For instance, they move from the woods with the Tragedians into the castle to a conversation with the king and queen without actually saying they want to enter Elsinore. When deciding whether to bring Hamlet to England, Rosencrantz concludes that they might as well continue on the path on which they are already. Stoppard criticizes this passivity. The title characters are able to make a life-changing decision when they discover that their letter contains an order to kill Hamlet. Instead, they decide to do nothing and the result is their deaths.

Metatheatre

Metatheatre is a central structural element of "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead". Metatheatrical scenes, that is, scenes that are staged as plays, dumb shows, or commentaries on dramatic theory and practice, are prominent in both Stoppard’s play and Shakespeare’s original tragedyHamlet . In "Hamlet", metatheatrical elements include the Player’s speech (2.2), Hamlet’s advice to the Players (3.2), and the meta-play "The Mousetrap" (3.3). Since Rosencrantz & Guildenstern are characters from "Hamlet" itself, Stoppard’s entire play can be considered a piece of metatheatre. However, this first level of metatheatre is deepened and complicated by frequent briefer and more intense metatheatrical episodes; see, for example, the Players’ pantomimes of "Hamlet" in Acts 2 and 3, Rosencrantz & Guildenstern’s obsessive role-playing, and the Player’s "death" in Act 3. Bernardina da Silveira Pinheiro observes that Stoppard uses metatheatrical devices to produce a "parody " of the key elements of Shakespeare’s "Hamlet" that includes foregrounding two minor characters considered "nonentities" in the original tragedy.cite book | first= Bernardina da Silveira | last=Pinheiro | coauthors=Resende, Aimara da Cunha, ed.| chapter=Stoppard’s and Shakespeare’s Views on Metatheater | title=Foreign Accents: Brazilian Readings of Shakespeare | location=Newark, DE | publisher=University of Delaware Press | pages=p. 185, 194 | year=2002 | isbn=0874137535 | url=http://books.google.com/books?id=P7yxUiVthVkC&pg=PA185 |accessdate=2008-06-24] Pinheiro notes that Stoppard alters the focus of Hamlet’s "play-within-a-play " so that it reveals the ultimate fate of thetragicomedy ’s anti-heroes, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. However, this alteration ultimately culminates in an absurdist anti-climax that runs counter to the effect of "The Mousetrap" in Hamlet, which effectively reveals the guilt of the King. While Rosencrantz and Guildenstern confront a mirror image of their future deaths in the metadramatic spectacle staged by the Players, they fail to recognize themselves in it or gain any insight into their identities or purpose.Notable productions

United Kingdom

The play had its first incarnation as a 1964 one-act, "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Meet King Lear". The expanded version under the current title was first staged at the

Edinburgh Festival Fringe August 24 ,1966 by the Oxford Theatre Group. The play debuted inLondon with a National Theatre production directed byDerek Goldby at theOld Vic . It premiered onApril 11 ,1967 withJohn Stride as Rosencrantz,Edward Petherbridge as Guildenstern,Graham Crowden as the Player, andJohn McEnery as Hamlet.Broadway and Off-Broadway

The Royal National Theatre production of "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern" had a year-long Broadway run from

October 9 ,1967 throughOctober 19 ,1968 , initially at theAlvin Theatre , then transferring to theEugene O'Neill Theatre onJanuary 8 ,1968 . The production, which was Stoppard's first on Broadway, totalled eight previews and 420 performances.. It was directed byDerek Goldby and designed byDesmond Heeley and starredPaul Hecht as the Player,Brian Murray as Rosencrantz and John Wood as Guildenstern. The play was nominated for eightTony Award s, and won four: Best Play, Scenic and Costume Design, and Producer; the director and the three leading actors were nominated for Tonys, but did not win. [cite news | author= | title=Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead Tony Award Info | url=http://www.broadwayworld.com/tonyawardsshowinfo.cfm?showname=Rosencrantz%20and%20Guildenstern%20Are%20Dead | work=BroadwayWorld | date=2008 | accessdate=2008-06-23] The play also won Best Play from theNew York Drama Critics Circle in 1968, and Outstanding Production from the Outer Critics Circle in 1969.The play had a 1987 New York revival by Roundabout Theatre at the

Union Square Theatre , directed byRobert Carsen and featuring John Wood as the Player,Stephen Lang as Rosencrantz andJohn Rubinstein as Guildenstern. It ran for 40 performances fromApril 29 toJune 28 ,1987 .Film adaptation

The play was adapted for a film released in February 1990, with screenplay and direction by Stoppard - his only film directing credit. The cast included

Gary Oldman as Rosencrantz,Tim Roth as Guildenstern,Richard Dreyfuss as the Player,Joanna Roth as Ophelia,Ian Richardson as Polonius,Joanna Miles as Gertrude,Donald Sumpter as Claudius, andIain Glen as Hamlet.References

Further reading

*

External links

*ibdb title|2959

*" [http://www.lortel.org/LLA_archive/index.cfm?search_by=show&id=2005 Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead] " at theInternet Off-Broadway Database

* [http://www.sondheimguide.com/Stoppard/chronology.html A Tom Stoppard Bibliography: Chronology] at sondheimguide.com.

* [http://www.starkravingsane.co.nr/ Stark Raving Sane - unofficial fansite for the play and film]

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.