- Palmitoylethanolamide

-

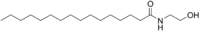

Palmitoylethanolamide  N-(2-hydroxyethyl)hexadecanamideOther namesPalmidrol; N-Palmitoylethanolamine; Palmitamide MEA; Palmitylethanolamide; Hydroxyethylpalmitamide

N-(2-hydroxyethyl)hexadecanamideOther namesPalmidrol; N-Palmitoylethanolamine; Palmitamide MEA; Palmitylethanolamide; HydroxyethylpalmitamideIdentifiers CAS number 544-31-0

PubChem 4671 UNII 6R8T1UDM3V

Jmol-3D images Image 1 - CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)NCCO

Properties Molecular formula C18H37NO2 Molar mass 299.49 Appearance White solid Density 0.91g/cm3 Melting point 59-60 °C

Boiling point 461.5°C @ 760mmHg

Solubility in other solvents soluble in ethanol,chloroform,THF and DMSO Hazards Flash point 323.9°C  (verify) (what is:

(verify) (what is:  /

/ ?)

?)

Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa)Infobox references Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) is an endogenous fatty acid amide, belonging to the class of endocannabinoids. PEA has been demonstrated to bind to a receptor in the cell-nucleus (a nuclear receptor) and exerts a great variety of biological functions related to chronic pain and inflammation. The main target is thought to be the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α)[1][2]. PEA also has affinity to cannabinoid-like G-coupled receptors GPR55 and GPR119.[3] However, its affinity for the classical cannabis receptors CB1and CB2 is absent. Therefore, PEA (and its structural analogue oleoylethanolamide, OEA) can not strictly be considered classic endocannabinoids. [4]

PEA has been shown to have anti-inflammatory[2], anti-nociceptive [5], neuroprotective[6], and anticonvulsant properties [7]

Palmitoylethanolamide is available for clinical use and is marketed by the Italian company Epitech under the trade name Normast.[8] Two different formulations have been developed, a ultra-micronized formulation of palmitoylethanolamide for sublingual use, containing 600 mg, and palmitoylethanolamide in a tablet, in 300 and 600 mg.

Contents

Early studies

In 1968 the first paper on PEA was indexed in Pubmed and since then more than 200 entries can be found using the keyword 'palmitoylethanolamide'. [9] In the 1990s the relation between anandamide and PEA was described, and the expression of receptors sensitive for those two molecules on mast cells was first demonstrated. [10] In this period more insight into the function of the endogenous fatty acid derivatives emerged, and compounds such as oleamide, palmitoylethanolamide, 2-lineoylglycerol, 2-palmitoylglycerol were explored for their capacity to modulate pain sensitivity and inflammation via endocannabinoid signalling. [11][12] One group demonstrated that PEA could alleviate, in a dose-dependent manner, pain behaviors elicited in mice-pain models and could downregulate hyperactive mast cells. [13][14] PEA and related compounds such as anandamide also seem to have synergistic effects in models of pain and analgesia. [15]

Animal models

In a variety of animal models PEA seems promising, and researchers could demonstrate relevant clinical activity in a variety of disorders, from multiple sclerosis to neuropathic pain. [16] [17]

In the so called mice forced swimming test palmitoylethanolamide was comparable in anti-depressant effects to fluoxetine. [18] Palmitoylethanolamide could reduced the raised intraocular pressure in glaucoma. [19] The compound could also reduce neurological deficit in a spinal trauma model, through the reduction of mast cell infiltration and activation. Palmitoylethanolamide in this model also reduced the activation of microglia and astrocytes. [20] Its activity as an inhibitor of inflammation could counteracts reactive astrogliosis induced by beta-amyloid peptide, in a model relevant for neurodegeneration, most probably via the PPAR-α mechanism of action. [21] In models of stroke and other traumata of the central nervous system, palmitoylethanolamide exerted neuroprotective properties. [22] [6] [23] [24] [25]

Animal models of chronic pain and inflammation

Chronic pain and neuropathic pain are indications for which there is high unmet need in the clinic. PEA has been tested In a variety of animal models for chronic and neuropathic pain. As Cannabinoids such as THC have been proven to be effective in neuropathic pain states, it makes sense to further explore the analgesic efficacy of endocannabinoids. [26] The analgesic and antihyperalgesic effects of PEA in two models of acute and persistent pain seemed to be explained at least partly via the de novo neurosteroid synthesis. [27] [28] In chronic granulomatous pain and inflammation model PEA could prevent nerve formation and sprouting, mechanical allodynia, and PEA inhibited dorsal root ganglia activation, which is a hallmark for winding up in neuropathic pain. [29] The mechanism of action of PEA as an analgesic and anti-inflammatory drug is probably based on different aspects. PEA inhibits the release of both preformed and newly synthesised mast cell mediators, such as histamine and TNF-alpha. [30]PEA, as well as its analogue adelmidrol (di-amide derivative of azelaic acid) both can down-regulate mast cells. [31] PEA reduces the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and prevents IkB-alpha degradation and p65 NF-kappaB nuclear translocation, the latter related to PEA as a endogenous PPAR-alpha agonist. [32]

In a model of visceral pain (inflammation of the urinary bladder) PEA was able to attenuate the viscero-visceral hyper-reflexia induced by inflammation of the urinary bladder, one of the reasons why PEA is currently explored in the painful bladdersyndrome. [33] In a different model for bladder pain, the turpentine-induced urinary bladder inflammation in the rat, PEA also attenuated a referred hyperalgesia in a dose-dependent way. [34] Chronic pelvic pain in patients indeed seems to respond favourably to a treatment with PEA. [35] [36] PEA seems to be produced in human as well as in animals as a biological response and a repair mechanism in chronic inflammation and chronic pain. [37]

ALIAmide and glia-modulator

PEA is has physico-chemical properties comparable to anandamide and is mostly referred to as belonging to the class of endogenous cannabinoids. Lipid molecules like PEA often act as signaling molecules, activating intracellular and membrane-associated receptors to regulate a variety of physiological functions. The signaling lipid PEA is known to activate intracellular, nuclear and membrane-associated receptors and regulate many physiological functions related to the inflammatory cascade and chronic pain states. Endocannabinoid lipids like PEA are widely distributed in nature, in a variety of plant, invertebrate, and mammalian tissues.[38]

PEA's mechanism of action sometimes is described using the acronym ALIA. [10] ALIA stands for Autacoid Local Injury (or inflammation) Antagonism, and PEA under this nomenclature is an ALIAmide. It was the group of the Nobel price laureate Rita Levi-Montalcini who in 1993 first presented evidence supporting that lipid amides of the N-acylethanolamine type (such as PEA) are potential prototypes of naturally occurring molecules capable of modulating mast cell activation and her group coined in that paper the acronym ALIA. [39] An autocoid is a regulating molecule, locally produced. Prostaglandins are classical examples of autocoids. An ALIAmide is an autocoid synthesized in response to injury or inflammation, and acting locally to counteract such pathology. PEA is a classical example of an ALIAmide. The mast cell soon after the breakthrough paper of Levi-Montalcini indeed appeared to be an important target for the anti-inflammatory activity of PEA, and in the period 1993-2011 at least 25 papers were published on the various effects of PEA on the mast cell. Since 2005 we understand that much of the biological effects on cells as the mast cell, most probably can be understood via its affinity of the PPARα receptor. Even rapid analgesic activity is partly described via the PPARα interaction. [40] Mast cells are often found in proximity to sensory nerve endings and their degradation can enhance the nociceptive signal, the reason why peripheral mast cells are considered to be pro-inflammatory and pro-nociceptive. [41] Mast cells also can be found in the spinal dura, the thalamus and the dura mater. Meanwhile, due to PEA's affinity to the PPARα receptor and due to the wide presence of those receptors in the central nervous system, especially also in glia and astrocytes [42][28], PEA's activity is currently seen as an important new inroad in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Glia and astrocytes play a key role in the winding up phenomena and central sensitization. [43] [44]

Clinical relevance

PEA has been explored in man in various clinical trials in a variety of pain states, as well as in pet animals, for inflammatory and painsyndromes. [45] [46] [47] [48] [49] [50] Its positive influence in atopic eczema for instance seems to originate from PPAR alpha activation. [51] [45] PEA is available for human use as food for medical purposes in Italy and Spain and as a diet supplement in the Netherlands. A parent moleule, adelmidrol, is available as a topical preparation for dermatological indications. [52]

From a clinical perspective the most important and promising indications for palmitoylethanolamide are linked to neuropathic and chronic pain states, such as diabetic neuropathic pain, sciatic pain, pelvic pain and entrapment neuropathic painstates. [46] [47] [53] [54] [37] [55] In a blind pilot trial in 25 patients affected by temporomandibular joint's (TMJ) osteoarthritis or synovitis pain, patients were randomly to PEA or ibuprofen 600 mg 3 times a day for 2 weeks. Pain decrease after two weeks of treatment was significantly higher PEA treated patients than in patients receiving the NSAID) (p=0.0001). Masticatory function also improves more on PEA compared to the NSAID (p=0.0001).

One of the targets of PEA is the glia. [56] Modern neurobiological research increasingly points out the relevance of the glia and asterocytes in the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain. One even coined the term gliopathic pain as an alternative for neuropathic pain. [57] Glia and asterocytes therefore are an important new target for the development of new analgesic compounds in the treatment of neuropathic pain. [58]

Treating neuropathic pain prescribing the current anti-neuropathic pain drugs, belonging to the classes of antidepressants and anticonvulsants, is often not satisfactory. [59] New drugs aiming for different non-neuronal targets, in this case the glia, such as palmitoylethanolamide, are needed. [60]

Metabolism

PEA is metabolized by cellular enzymes, fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and N-acylethanolamine-hydrolyzing acid amidase (NAAA), the latter of which has more specificity toward PEA over other fatty acid amides.[61] Due to this cellular metabolism, it seems that dose adjustment for renal insufficiency will be unnecessary, although formal human studies are not yet available. To date, no drug interactions have been reported in literature, neither any clinical relevant or dose-limiting side effect.

See also

References

- ^ O'Sullivan, S. E. (2007). "Cannabinoids go nuclear: evidence for activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors". British journal of pharmacology 152 (5): 576–582. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707423. PMC 2190029. PMID 17704824. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2190029.

- ^ a b Lo Verme, J.; Fu, J.; Astarita, G.; La Rana, G.; Russo, R.; Calignano, A.; Piomelli, D. (2005). "The nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha mediates the anti-inflammatory actions of palmitoylethanolamide". Molecular pharmacology 67 (1): 15–19. doi:10.1124/mol.104.006353. PMID 15465922.

- ^ Godlewski, G.; Offertáler, L.; Wagner, J. A.; Kunos, G. (2009). "Receptors for acylethanolamides—GPR55 and GPR119". Prostaglandins & Other Lipid Mediators 89 (3-4): 105–297. doi:10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2009.07.001. PMC 2751869. PMID 19615459. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2751869.

- ^ O'Sullivan, S. E.; Kendall, D. A. (2010). "Cannabinoid activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: Potential for modulation of inflammatory disease". Immunobiology 215 (8): 611–616. doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2009.09.007. PMID 19833407.

- ^ Calignano a, L. R. G. (2001). "Antinociceptive activity of the endogenous fatty acid amide, palmitylethanolamide". Eur J Pharmacol. 419 (2–3): 191–198. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(01)00988-8. PMID 11426841.

- ^ a b Koch, M.; Kreutz, S.; Böttger, C.; Benz, A.; Maronde, E.; Ghadban, C.; Korf, H. W.; Dehghani, F. (2010). "Palmitoylethanolamide Protects Dentate Gyrus Granule Cells via Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-Alpha". Neurotoxicity Research 19 (2): 330–340. doi:10.1007/s12640-010-9166-2. PMID 20221904.

- ^ Lambert, D.M., Vandevoorde, S., Diependaele, G., Govaerts, S.J., Robert, A.R. (2001). "Anticonvulsant activity of N-palmitoylethanolamide, a putative endocannabinoid, in mice.". Epilepsia 42 (3): 321-7. PMID 11442148.

- ^ Normast®, palmitoylethanolamide in neuropathic sciatic pain: clinical results. Behandelcentrum Neuropathische Pijn [Treatment Neuropathic Pain]. Accessed 23 September 2011.

- ^ Benvenuti, F.; Lattanzi, F.; De Gori, A.; Tarli, P. (1968). "Activity of some derivatives of palmitoylethanolamide on carragenine-induced edema in the rat paw". Bollettino della Societa italiana di biologia sperimentale 44 (9): 809–813. PMID 5699335.

- ^ a b Facci, L.; Dal Toso, R.; Romanello, S.; Buriani, A.; Skaper, S. D.; Leon, A. (1995). "Mast cells express a peripheral cannabinoid receptor with differential sensitivity to anandamide and palmitoylethanolamide". PNAS 92 (8): 3376–3380. PMC 42169. PMID 7724569. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=42169.

- ^ Walker, J. M.; Krey, J. F.; Chu, C. J.; Huang, S. M. (2002). "Endocannabinoids and related fatty acid derivatives in pain modulation". Chemistry and physics of lipids 121 (1–2): 159–172. PMID 12505698.

- ^ Lambert, D. M.; Vandevoorde, S.; Jonsson, K. O.; Fowler, C. J. (2002). "The palmitoylethanolamide family: A new class of anti-inflammatory agents?". Current medicinal chemistry 9 (6): 663–674. PMID 11945130.

- ^ Calignano a, L. R. G. (2001). "Antinociceptive activity of the endogenous fatty acid amide, palmitylethanolamide". Eur J Pharmacol. 419 (2–3): 191–198. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(01)00988-8. PMID 11426841.

- ^ Mazzari, S.; Canella, R.; Petrelli, L.; Marcolongo, G.; Leon, A. (1996). "N-(2-hydroxyethyl)hexadecanamide is orally active in reducing edema formation and inflammatory hyperalgesia by down-modulating mast cell activation". European journal of pharmacology 300 (3): 227–236. PMID 8739213.

- ^ Piomelli, D.; Calignano, A.; Rana, G. L.; Giuffrida, A. (1998). "Control of pain initiation by endogenous cannabinoids". Nature 394 (6690): 277–281. doi:10.1038/28393. PMID 9685157.

- ^ Loría, F.; Petrosino, S.; Mestre, L.; Spagnolo, A.; Correa, F.; Hernangómez, M.; Guaza, C.; Di Marzo, V. et al. (2008). "Study of the regulation of the endocannabinoid system in a virus model of multiple sclerosis reveals a therapeutic effect of palmitoylethanolamide". European Journal of Neuroscience 28 (4): 633–641. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06377.x. PMID 18657182.

- ^ Costa, B.; Comelli, F.; Bettoni, I.; Colleoni, M.; Giagnoni, G. (2008). "The endogenous fatty acid amide, palmitoylethanolamide, has anti-allodynic and anti-hyperalgesic effects in a murine model of neuropathic pain: Involvement of CB1, TRPV1 and PPARγ receptors and neurotrophic factors". PAIN 139 (3): 541–550. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.003. PMID 18602217.

- ^ Yu, H. L.; Deng, X. Q.; Li, Y. J.; Li, Y. C.; Quan, Z. S.; Sun, X. Y. (2011). "N-palmitoylethanolamide, an endocannabinoid, exhibits antidepressant effects in the forced swim test and the tail suspension test in mice". Pharmacological reports : PR 63 (3): 834–839. PMID 21857095.

- ^ Gagliano, C.; Ortisi, E.; Pulvirenti, L.; Reibaldi, M.; Scollo, D.; Amato, R.; Avitabile, T.; Longo, A. (2011). "Ocular Hypotensive Effect of Oral Palmitoyl-ethanolamide: A Clinical Trial". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 52 (9): 6096–6100. doi:10.1167/iovs.10-7057. PMID 21705689.

- ^ Esposito, E.; Paterniti, I.; Mazzon, E.; Genovese, T.; Di Paola, R.; Galuppo, M.; Cuzzocrea, S. (2011). "Effects of palmitoylethanolamide on release of mast cell peptidases and neurotrophic factors after spinal cord injury". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 25 (6): 1099–1112. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2011.02.006. PMID 21354467.

- ^ Scuderi, C.; Esposito, G.; Blasio, A.; Valenza, M.; Arietti, P.; Steardo, L.; Carnuccio, R.; De Filippis, D. et al. (2011). "Palmitoylethanolamide counteracts reactive astrogliosis induced by beta-amyloid peptide". Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine: no. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01267.x. PMID 21255263.

- ^ PMID 220353771 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ^ Garcia-Ovejero, D.; Arevalo-Martin, A.; Petrosino, S.; Docagne, F.; Hagen, C.; Bisogno, T.; Watanabe, M.; Guaza, C. et al. (2009). "The endocannabinoid system is modulated in response to spinal cord injury in rats". Neurobiology of Disease 33 (1): 57–71. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.015. PMID 18930143.

- ^ Schomacher, M.; Müller, H. D.; Sommer, C.; Schwab, S.; Schäbitz, W. R. D. (2008). "Endocannabinoids mediate neuroprotection after transient focal cerebral ischemia". Brain Research 1240: 213–220. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2008.09.019. PMID 18823959.

- ^ Sasso, O.; Russo, R.; Vitiello, S.; Mattace Raso, G.; d’Agostino, G.; Iacono, A.; La Rana, G.; Vallée, M. et al. (2011). "Implication of allopregnanolone in the antinociceptive effect of N-palmitoylethanolamide in acute or persistent pain". PAIN. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.010. PMID 21890273.

- ^ Ware, M. A.; Wang, T.; Shapiro, S.; Robinson, A.; Ducruet, T.; Huynh, T.; Gamsa, A.; Bennett, G. J. et al. (2010). "Smoked cannabis for chronic neuropathic pain: A randomized controlled trial". Canadian Medical Association Journal 182 (14): E694–E701. doi:10.1503/cmaj.091414. PMC 2950205. PMID 20805210. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2950205.

- ^ Skaper, S. D.; Buriani, A.; Dal Toso, R.; Petrelli, L.; Romanello, S.; Facci, L.; Leon, A. (1996). "The ALIAmide palmitoylethanolamide and cannabinoids, but not anandamide, are protective in a delayed postglutamate paradigm of excitotoxic death in cerebellar granule neurons". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93 (9): 3984–3989. PMC 39472. PMID 8633002. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=39472.

- ^ a b Raso, G. M.; Esposito, E.; Vitiello, S.; Iacono, A.; Santoro, A.; d'Agostino, G.; Sasso, O.; Russo, R. et al. (2011). "Palmitoylethanolamide stimulation induces allopregnanolone synthesis in C6 Cells and primary astrocytes: Involvement of peroxisome-proliferator activated receptor-α". Journal of neuroendocrinology 23 (7): 591–600. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02152.x. PMID 21554431.

- ^ De Filippis, D.; Luongo, L.; Cipriano, M.; Palazzo, E.; Cinelli, M. P.; De Novellis, V.; Maione, S.; Iuvone, T. (2011). "Palmitoylethanolamide reduces granuloma-induced hyperalgesia by modulation of mast cell activation in rats". Molecular Pain 7: 3. doi:10.1186/1744-8069-7-3. PMC 3034677. PMID 21219627. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3034677.

- ^ Cerrato, S.; Brazis, P.; Della Valle, M. F.; Miolo, A.; Puigdemont, A. (2010). "Effects of palmitoylethanolamide on immunologically induced histamine, PGD2 and TNFα release from canine skin mast cells". Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology 133 (1): 9–15. doi:10.1016/j.vetimm.2009.06.011. PMID 19625089.

- ^ De Filippis, D.; d’Amico, A.; Cinelli, M. P.; Esposito, G.; Di Marzo, V.; Iuvone, T. (2009). "Adelmidrol, a palmitoylethanolamide analogue, reduces chronic inflammation in a carrageenin-granuloma model in rats". Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 13 (6): 1086–1095. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00353.x. PMID 18429935.

- ^ d'Agostino, G.; La Rana, G.; Russo, R.; Sasso, O.; Iacono, A.; Esposito, E.; Mattace Raso, G.; Cuzzocrea, S. et al. (2009). "Central administration of palmitoylethanolamide reduces hyperalgesia in mice via inhibition of NF-κB nuclear signalling in dorsal root ganglia". European Journal of Pharmacology 613 (1–3): 54–59. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.04.022. PMID 19386271.

- ^ Jaggar, S. I.; Hasnie, F. S.; Sellaturay, S.; Rice, A. S. (1998). "The anti-hyperalgesic actions of the cannabinoid anandamide and the putative CB2 receptor agonist palmitoylethanolamide in visceral and somatic inflammatory pain". Pain 76 (1–2): 189–199. PMID 9696473.

- ^ Farquhar-Smith, W. P.; Rice, A. S. (2001). "Administration of endocannabinoids prevents a referred hyperalgesia associated with inflammation of the urinary bladder". Anesthesiology 94 (3): 507–513; discussion 513. PMID 11374613.

- ^ Calabrò, R. S.; Gervasi, G.; Marino, S.; Mondo, P. N.; Bramanti, P. (2010). "Misdiagnosed Chronic Pelvic Pain: Pudendal Neuralgia Responding to a Novel Use of Palmitoylethanolamide". Pain Medicine 11 (5): 781–784. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00823.x. PMID 20345619.

- ^ Indraccolo, U.; Barbieri, F. (2010). "Effect of palmitoylethanolamide–polydatin combination on chronic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis: Preliminary observations". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 150 (1): 76–79. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.01.008. PMID 20176435.

- ^ a b Darmani, N. A.; Izzo, A. A.; Degenhardt, B.; Valenti, M.; Scaglione, G.; Capasso, R.; Sorrentini, I.; Di Marzo, V. (2005). "Involvement of the cannabimimetic compound, N-palmitoyl-ethanolamine, in inflammatory and neuropathic conditions: Review of the available pre-clinical data, and first human studies". Neuropharmacology 48 (8): 1154–1163. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.001. PMID 15910891.

- ^ Buznikov, G. A.; Nikitina, L. A.; Bezuglov, V. V.; Francisco, M. E. Y.; Boysen, G.; Obispo-Peak, I. N.; Peterson, R. E.; Weiss, E. R. et al. (2010). "A Putative 'Pre-Nervous' Endocannabinoid System in Early Echinoderm Development". Developmental Neuroscience 32 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1159/000235758. PMC 2866581. PMID 19907129. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2866581.

- ^ Aloe, L.; Leon, A.; Levi-Montalcini, R. (1993). "A proposed autacoid mechanism controlling mastocyte behaviour". Agents and actions 39 Spec No: C145–C147. PMID 7505999.

- ^ Loverme, J.; Russo, R.; La Rana, G.; Fu, J.; Farthing, J.; Mattace-Raso, G.; Meli, R.; Hohmann, A. et al. (2006). "Rapid Broad-Spectrum Analgesia through Activation of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor- ". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 319 (3): 1051–1061. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.111385. PMID 16997973.

- ^ Xanthos, D. N.; Gaderer, S.; Drdla, R.; Nuro, E.; Abramova, A.; Ellmeier, W.; Sandkühler, J. R. (2011). "Central nervous system mast cells in peripheral inflammatory nociception". Molecular Pain 7: 42. doi:10.1186/1744-8069-7-42. PMC 3123586. PMID 21639869. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3123586.

- ^ Cullingford, T. E.; Bhakoo, K.; Peuchen, S.; Dolphin, C. T.; Patel, R.; Clark, J. B. (1998). "Distribution of mRNAs encoding the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha, beta, and gamma and the retinoid X receptor alpha, beta, and gamma in rat central nervous system". Journal of neurochemistry 70 (4): 1366–1375. PMID 9523552.

- ^ Nakagawa, T.; Kaneko, S. (2010). "Spinal astrocytes as therapeutic targets for pathological pain". Journal of pharmacological sciences 114 (4): 347–353. PMID 21081837.

- ^ Guasti, L.; Richardson, D.; Jhaveri, M.; Eldeeb, K.; Barrett, D.; Elphick, M. R.; Alexander, S. P.; Kendall, D. et al. (2009). "Minocycline treatment inhibits microglial activation and alters spinal levels of endocannabinoids in a rat model of neuropathic pain". Molecular Pain 5: 35. doi:10.1186/1744-8069-5-35. PMC 2719614. PMID 19570201. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2719614.

- ^ a b Eberlein, B.; Eicke, C.; Reinhardt, H. -W.; Ring, J. (2007). "Adjuvant treatment of atopic eczema: Assessment of an emollient containing N-palmitoylethanolamine (ATOPA study)". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 22 (1): 73–82. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02351.x. PMID 18181976.

- ^ a b Conigliaro, R.; Drago, V.; Foster, P. S.; Schievano, C.; Di Marzo, V. (2011). "Use of palmitoylethanolamide in the entrapment neuropathy of the median in the wrist". Minerva medica 102 (2): 141–147. PMID 21483401.

- ^ a b Indraccolo, U.; Barbieri, F. (2010). "Effect of palmitoylethanolamide–polydatin combination on chronic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis: Preliminary observations". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 150 (1): 76–79. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.01.008. PMID 20176435.

- ^ Phan, N. Q.; Siepmann, D.; Gralow, I.; Ständer, S. (2009). "Adjuvant topical therapy with a cannabinoid receptor agonist in facial postherpetic neuralgia". Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft 8 (2): 88–91. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2009.07213.x. PMID 19744255.

- ^ Cerrato, S.; Brazis, P.; Valle, M. F. D.; Miolo, A.; Petrosino, S.; Marzo, V. D.; Puigdemont, A. (2011). "Effects of palmitoylethanolamide on the cutaneous allergic inflammatory response in Ascaris hypersensitive Beagle dogs". The Veterinary Journal. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.04.002. PMID 21601500.

- ^ O'Sullivan, S. E.; Kendall, D. A. (2010). "Cannabinoid activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: Potential for modulation of inflammatory disease". Immunobiology 215 (8): 611–616. doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2009.09.007. PMID 19833407.

- ^ Hatano, Y.; Man, M. Q.; Uchida, Y.; Crumrine, D.; Mauro, T. M.; Feingold, K. R.; Elias, P. M.; Holleran, W. M. (2010). "Murine atopic dermatitis responds to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α, β/δ(but not γ), and liver-X-receptor activators". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 125 (1): 160–169.e1–169. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.06.049. PMC 2859962. PMID 19818482. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2859962.

- ^ Pulvirenti, N.; Nasca, M. R.; Micali, G. (2007). "Topical adelmidrol 2% emulsion, a novel aliamide, in the treatment of mild atopic dermatitis in pediatric subjects: A pilot study". Acta dermatovenerologica Croatica : ADC 15 (2): 80–83. PMID 17631786.

- ^ Petrosino, S.; Iuvone, T.; Di Marzo, V. (2010). "N-palmitoyl-ethanolamine: Biochemistry and new therapeutic opportunities". Biochimie 92 (6): 724–727. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2010.01.006. PMID 20096327.

- ^ Phan, N. Q.; Siepmann, D.; Gralow, I.; Ständer, S. (2009). "Adjuvant topical therapy with a cannabinoid receptor agonist in facial postherpetic neuralgia". Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft 8 (2): 88–91. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2009.07213.x. PMID 19744255.

- ^ Normast®, palmitoylethanolamide in neuropathic sciatic pain: clinical results. Behandelcentrum Neuropathische Pijn [Treatment Neuropathic Pain]. Accessed 23 September 2011.

- ^ Muccioli, G. G.; Stella, N. (2008). "Microglia produce and hydrolyze palmitoylethanolamide". Neuropharmacology 54 (1): 16–22. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.05.015. PMC 2254322. PMID 17631917. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2254322.

- ^ Ohara, P. T.; Vit, J. -P.; Bhargava, A.; Romero, M.; Sundberg, C.; Charles, A. C.; Jasmin, L. (2009). "Gliopathic Pain: When Satellite Glial Cells Go Bad". The Neuroscientist 15 (5): 450–463. doi:10.1177/1073858409336094. PMC 2852320. PMID 19826169. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2852320.

- ^ Milligan, E. D.; Watkins, L. R. (2009). "Pathological and protective roles of glia in chronic pain". Nature Reviews Neuroscience 10 (1): 23–36. doi:10.1038/nrn2533. PMC 2752436. PMID 19096368. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2752436.

- ^ Finnerup, N. B.; Sindrup, S. R. H.; Jensen, T. S. (2010). "The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain". PAIN 150 (3): 573–581. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.019. PMID 20705215.

- ^ Benarroch, E. E. (2010). "Central neuron-glia interactions and neuropathic pain: Overview of recent concepts and clinical implications". Neurology 75 (3): 273–278. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e984. PMID 20644154.

- ^ Tsuboi, K.; Takezaki, N.; Ueda, N. (2007). "The N-Acylethanolamine-Hydrolyzing Acid Amidase (NAAA)". Chemistry & Biodiversity 4 (8): 1914. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200790159. PMID 17712833.

Cannabinoids Plant cannabinoids Cannabinoid metabolites 8,11-DiOH-THC · 11-COOH-THC · 11-OH-THC

Endogenous cannabinoids Arachidonoyl ethanolamide (Anandamide or AEA) · 2-Arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) · 2-Arachidonyl glyceryl ether (noladin ether) · Virodhamine · Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) · N-Arachidonoyl dopamine (NADA) · Oleamide · RVD-Hpα

Synthetic cannabinoid

receptor agonistsClassical cannabinoids

(Dibenzopyrans)A-40174 · A-41988 · A-42574 · Ajulemic acid · AM-087 · AM-411 · AM-855 · AM-905 · AM-906 · AM-919 · AM-926 · AM-938 · AM-4030 · AMG-1 · AMG-3 · AMG-36 · AMG-41 · Dexanabinol (HU-211) · DMHP · Dronabinol · HHC · HU-210 · JWH-051 · JWH-133 · JWH-139 · JWH-161 · JWH-229 · JWH-359 · KM-233 · L-759,633 · L-759,656 · Levonantradol (CP 50,5561) · Nabazenil · Nabidrox (Canbisol) · Nabilone · Nabitan · Naboctate · O-581 · O-774 · O-806 · O-823 · O-1057 · O-1125 · O-1238 · O-2365 · O-2372 · O-2373 · O-2383 · O-2426 · O-2484 · O-2545 · O-2694 · O-2715 · O-2716 · O-3223 · O-3226 · Parahexyl · Perrottetinene · Pirnabine · THC-O-acetate · THC-O-phosphate

Nonclassical cannabinoidsBenzoylindoles1-Butyl-3-(2-methoxybenzoyl)indole · 1-Butyl-3-(4-methoxybenzoyl)indole · 1-Pentyl-3-(2-methoxybenzoyl)indole · AM-630 · AM-679 · AM-694 · AM-1241 · AM-2233 · GW-405,833 (L-768,242) · Pravadoline · RCS-4 · WIN 54,461

NaphthoylindolesNaphthylmethylindolesJWH-175 · JWH-184 · JWH-185 · JWH-192 · JWH-194 · JWH-195 · JWH-196 · JWH-197 · JWH-199

PhenylacetylindolesCannabipiperidiethanone · JWH-167 · JWH-203 · JWH-249 · JWH-250 · JWH-251 · JWH-302 · RCS-8

NaphthoylpyrrolesEicosanoidsAM-883 · Arachidonyl-2'-chloroethylamide (ACEA) · Arachidonylcyclopropylamide (ACPA) · Methanandamide (AM-356) · O-585 · O-689 · O-1812 · O-1860 · O-1861

Others(1-Pentylindol-3-yl)-(2,2,3,3-tetramethylcyclopropyl)methanone · N-(S)-Fenchyl-1-(2-morpholinoethyl)-7-methoxyindole-3-carboxamide · A-796,260 · A-834,735 · A-836,339 · Abnormal cannabidiol · AB-001 · AM-1248 · AZ-11713908 · BAY 38-7271 · BAY 59-3074 · CB-13 · CB-86 · GW-842,166X · JWH-171 · JWH-176 · JTE 7-31 · Leelamine · MDA-19 · O-1918 · O-2220 · Org 28312 · Org 28611 · SER-601 · VSN-16 · WIN 56,098

Allosteric modulators of

cannabinoid receptorsOrg 27569 · Org 27759 · Org 29647

Endocannabinoid

activity enhancersAM-404 · CAY-10401 · CAY-10429 · JZL184 · JZL195 · Arachidonoyl serotonin · O-1624 · PF-04457845 · PF-622 · PF-750 · PF-3845 · PHOP · URB-447 · URB-597 · URB-602 · URB-754 · Genistein · Arvanil · Olvanil · Kaempferol · Biochanin A

Cannabinoid receptor

antagonists and

inverse agonistsAM-251 · AM-281 · AM-630 · BML-190 · CAY-10508 · CB-25 · CB-52 · CB-86 · Drinabant · Hemopressin · Ibipinabant (SLV319) · JTE-907 · LY-320,135 · Taranabant (MK-0364) · MK-9470 · NESS-0327 · O-1184 · O-1248 · O-2050 · O-2654 · Otenabant · Rimonabant (SR141716) · SR144528 · Surinabant (SR147778) · TM-38837 · VCHSR

Categories:- Amides

- Biomolecules

- Lipids

- Fatty acid amides

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.