- Coal ball

-

Coal ball

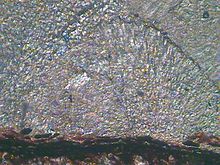

A coal ballComposition Primary Calcite Secondary Permineralised life forms Coal balls, despite their name, are calcium-rich masses of permineralised life forms, generally having a round shape. Coal balls were formed roughly 300 million years ago (mya), during the Carboniferous Period. They are exceptional at preserving organic matter, which makes them useful to scientists, who cut and peel the coal balls to research the geological past of the Earth.

In 1855, two English scientists, Joseph Dalton Hooker and Edward William Binney, discovered coal balls in England, and the initial research on coal balls was carried out in Europe. It was not until 1922 that coal balls were discovered and identified in North America. Since then, coal balls have been discovered in other countries and several theories on their formation have been proposed.

Coal balls can be found in coal seams across North America and Eurasia. North American coal balls are relatively widespread, both stratigraphically and geologically, as compared to coal balls from Europe. The oldest known coal balls were found in Germany and the former Czechoslovakia.

Contents

Discovery

Coal balls were first reported by Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker and Edward William Binney in northern England in 1855, and European scientists did much of the early work on these objects.[1][2] Coal balls in North America were found in coal seams in the 1890s,[3] although the connection to European coal balls was not made until Adolph Carl Noé made the connection in 1922,[4][5] whose coal ball was actually found by Gilbert Cady.[3]

Until 1922 coal balls were merely reported as "rock masses in the coal seams".[6] Since then hundreds of new species have been discovered in coal balls in other countries, and multiple paleobotanists have devised theories on the formation of coal balls.[2]

Formation

Upon discovering Westphalian-age (roughly 313 to 304 mya) coal balls in Yorkshire and Lancashire, England, Hooker and Binney proposed a theory on how coal balls were formed,[1][7] which is commonly agreed upon in scientific papers.[6][7][8]

Hooker and Binney believed that coal balls were formed in situ – organic matter gently accumulated near a peat bog and was permineralised, a process of fossilization in which mineral deposits form internal casts of organisms.[1][7] Water with a high dissolved mineral content was buried along with the plant matter in a peat bog. As the dissolved ions crystallised, concretions containing plant material were formed and preserved as rounded lumps of stone. This prevented coalification and preserved the peat, which eventually became a coal ball.[6] The process is considered permineralisation because the plant material is preserved by the surrounding minerals.[9] The majority of coal balls are found in bituminous and anthracite coal seams,[9][10] in locations where the peat was not compressed sufficiently to render the material into coal.[6][11]

Besides Hooker and Binney's analysis, Marie Stopes and David Watson analysed their own coal ball samples. Like Hooker and Binney they decided that coal balls formed in situ, but added that interaction with a marine environment was necessary for a coal ball to form.[12]

Contents

Notwithstanding the word "coal" in their name, coal balls are not made of coal (they are not flammable and useless for fuel),[11][13][14] but rather calcium-rich permineralised life forms,[11] mostly containing calcium carbonate, magnesium carbonate, iron pyrite, silica, and carbonate of lime.[15][16] Their sizes have been described as ranging from "the size of a walnut" to "large, round masses up to three feet in diameter",[17] as well as "about the size of a man's fist".[18]

Coal balls commonly contain microdolomites, products of aragonite,[11] and masses of organic matter at various stages of decomposition.[6][8][19] Hooker and Binney analysed a sample of a coal ball, finding "a lack of coniferous wood ... and fronds of ferns", and that the discovered plant matter "appeared to [have been arranged] just as they fell from the plants that produced them".[1]

In 1962, Sergius Mamay and Ellis Yochelson discovered signs of marine animal remains in North American coal balls.[20][21]

Preservation

The quality of preservation in coal balls varies from no preservation to the point of being able to analyse the cellular structures.[7] Some coal balls have been found to contain preserved root hairs,[22] and described as "more or less perfectly well-preserved"[23] and containing "beautifully anatomically-preserved plants ... not what used to be the plant – it is the plant",[24] while others have been described as "[containing] almost no preserved plant remains".[11]

The quality of preservation depends on the minerals contained in it, the speed of the burial process, and the degree of compression before undergoing permineralisation. Generally, coal balls resulting from remains that have a quick burial with little decay and pressure are more well preserved, although plant remains in most coal balls show various signs of decay and collapse, even in the same coal seam.[6] Coal balls containing quantities of iron sulphide have far lower preservation than coal balls permineralised by magnesium or calcium carbonate, which has earned them the name "chief curse of the coal ball hunter".[22]

Distribution

Coal balls were first found in England,[1] and later in other parts of Eurasia, including Belgium, Holland, former Czechoslovakia, Germany, the former Soviet Union, and more recently, China.[2][11] They were also encountered in North America, where, compared to Europe, they are relatively widespread,[2] from the Illinois Basin[25] to Ohio to the Appalachian region,[6] with ages varying from the later Stephanian (roughly 304 to 299 mya) to the later end of the Westphalian (roughly 313 to 304 mya). European coal balls are generally from the early end of the Westphalian Stage.[2] The oldest coal balls were of Namurian age (326 to 313 mya) and were discovered in Germany and former Czechoslovakia.[2]

Analysis

Thin sectioning was the first procedure used to analyse fossilised material contained in coal balls. The procedure was created and used by Hooker and Binney,[1][3][23][26] and involved cutting a coal ball with a diamond saw, flattening, polishing, and gluing the thin section to a slide, then placing it under a petrographic microscope for examination.[11][27] This process could be done with a machine, although the large amount of time needed and the inferior quality of samples produced by thin sectioning gave way to a more convenient method.[2][28]

The thin section technique was superseded by the now-common liquid peel technique in 1928.[2][26] In the liquid peel technique, peels are obtained by cutting the surface of a coal ball with a diamond saw, grinding the cut surface on a glass plate with carborundum to a smooth finish, and etching the cut and the surface with hydrochloric acid.[28] The acid dissolves the mineral matter from the coal ball, and will leave a projecting layer of plant cells.[22] Acetone should be applied and a piece of cellulose acetate.[16] This embeds the cells preserved in the coal ball into the cellulose acetate. Upon drying, the cellulose acetate can be removed from the coal ball with a razor and the obtained peel can be stained with a low-acidity stain and observed under a microscope.[8][22][29][30] Up to 50 peels can be extracted from 2 millimeters of coal ball with this method.[28]

X-ray powder diffraction has also been used to analyse coal balls.[11] In X-ray diffraction, X-rays of a predetermined wavelength are sent through a sample to examine its structure. It reveals information about the crystallographic structure, chemical composition, and physical properties of the examined material. The scattered intensity of the X-ray pattern is observed and analysed, with the measurements consisting of incident and scattered angle, polarisation, and wavelength or energy.[31]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f Hooker, Joseph Dalton; Edward William Binney (1855). "On the structure of certain limestone nodules enclosed in seams of bituminous coal, with a description of some trigonocarpons contained in them". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (Britain: Royal Society) 145: 149–156. doi:10.1098/rstl.1855.0006. JSTOR 108514.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Scott, Andrew C.; Rex, G (1985). "The formation and significance of Carboniferous coal balls". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 311: 123–137. JSTOR 2396976. http://digirep.rhul.ac.uk/file/c58e6257-7af3-2f87-0eeb-c9c521ae0dbb/1/38ScottandRex.pdf. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- ^ a b c Darrah, William Culp; Lyons, Paul C (1995). Historical Perspective of Early Twentieth Century Carboniferous Paleobotany in North America. United States of America: Geological Society of America. ISBN 0813711851.

- ^ Noé, Adolph C. (June 1923). "A Paleozoic Angiosperm". The Journal of Geology 31 (4): 344–347. Bibcode 1923JG.....31..344N. doi:10.1086/623025. JSTOR 30078443.

- ^ Noé, Adolph C. (30 March 1923). "Coal Balls". Science 57 (1474): 385. doi:10.1126/science.57.1474.385. JSTOR 1648633. PMID 17748916.

- ^ a b c d e f g Phillips, Tom; Matthew J. Avcin, Dwain Berggren. "Fossil Peats from the Illinois Basin: A guide to the study of coal balls of Pennsylvanian age". University of Illinois. http://library.isgs.uiuc.edu/Pubs/pdfs/ges/es11.pdf. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d Perkins, Thomas (1976). "Textures and Conditions of Formation of Middle Pennsylvanian Coal Balls, Central United States". University of Kansas. http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/dspace/bitstream/1808/3746/3/paleo.paper.082op.pdf. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ a b c "PBIO 460/560 Paleobotany; Cutting a Coal Ball". Archived from the original on 2011-07-28. http://www.ohio.edu/plantbio/staff/rothwell/pbio460-560/Cutting_a_Coal_Ball.htm. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ^ a b "coal ball (paleontology) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com Inc.. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/122951/coal-ball. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ "Paleobotany". Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 10 September 2011. http://www.cmnh.org/site/researchandcollections/Paleobotany.aspx. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Barwood, Henry L (1995). "Mineralogy and origin of coal balls". Geological Society of America North Central and South Central Section: 37.

- ^ Stopes, MC; Watson; DMS Watson (1908). "On the present distribution and origin of the calcareous concretions in coal seams, known as coal balls". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (Britain: Royal Society) 200: 167–218. Bibcode 1909RSPTB.200..167S. JSTOR 91931.

- ^ "a photo gallery of meteorwrongs". Archived from the original on 2011-07-28. http://meteorites.wustl.edu/meteorwrongs/m069.htm. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ^ "Origin of Coal". truedino.com. 2010 (last update). Archived from the original on 2011-07-28. http://truedino.com/origin_of_coal.htm. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ Lomax, James (1903). "On the occurrence of the nodular concretions (coal balls) in the lower coal measures". Report of the annual meeting (British Association for the Advancement of Science) 72: 811–812.

- ^ a b Gabel, Mark L.; Steven E. Dyche (February 1986). "Making Coal Ball Peels to Study Fossil Plants". The American Biology Teacher (University of California Press) 48 (2): 99–101. JSTOR 4448216.

- ^ Feliciano, José Maria (1 May 1924). "The Relation of Concretions to Coal Seams". The Journal of Geology (The University of Chicago Press) 32 (3): 230–239. Bibcode 1924JG.....32..230F. doi:10.1086/623086. JSTOR 30059936.

- ^ "Ore Deposits Under Study – Chicago University professor to engage in research work". Evening Independent: p. 13. 19 June 1923. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=xvFPAAAAIBAJ&sjid=zFQDAAAAIBAJ&dq=coal+balls&pg=3547%2C4532691. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Fossils – Window To The Past (Permineralisation)". Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/paleo/fossils/permin.html. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ Holmes, J; Scott A.C. (1981). "A note on the occurrence of marine animal remains in a Lancashire coal ball (Westphalian A)". Geological Magazine 118 (3): 307–308. doi:10.1017/S0016756800035809.

- ^ Mamay, Sergius H.; Ellis L. Yochelson (1962). "Occurrence and significance of marine animal remains in American coal balls". Geological Survey: 193–224.

- ^ a b c d Andrews, Henry N. (April 1946). "Coal Balls - A Key to the Past". The Scientific Monthly 62 (4): 327–334. JSTOR 18958.

- ^ a b Seward, Albert Charles (1898). Fossil plants: a text-book for students of botany and geology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84–87.

- ^ Phillips, Tom L. "T L 'Tommy' Phillips, Department of Plant Biology, University of Illinois". University of Illinois. Archived from the original on 2011-07-31. http://www.life.illinois.edu/plantbio/People/Faculty/Phillips.htm. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ DiMichele, William A; Tom L Phillips (1988). "Paleoecology of the Middle Pennsylvanian-Age Herrin Coal Swamp (Illinois) Near a Contemporaneous River System, the Walshville Paleochannel". Review of Paleobotany and Palyntology (Elsevier Science Publishers BV Amsterdam) 56: 151–176. doi:10.1016/0034-6667(88)90080-2. http://si-pddr.si.edu/jspui/bitstream/10088/7152/1/paleo_1988_DiMichele_Phillips_OldBen_RPP.pdf.

- ^ a b Phillips, Tom L.; Herman L. Pfefferkorn, Russel A. Peppers (1973). "Development of Paleobotany in the Illinois Basin" (PDF). Illinois State Geological Survey. http://library.isgs.uiuc.edu/Pubs/pdfs/circulars/c480.pdf. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ University of Chicago Department. of Geology (1915). The Journal of Geology. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ a b c Seward, A. C. (2010). Plant Life Through the Ages: A Geological and Botanical Retrospect. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1108016006.

- ^ "Coal Ball Peel Technique". University of Ohio. Archived from the original on 2 August 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60dDh08bE. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ^ "NMNH Paleobiology: Illustration Techniques". paleobiology.si.edu. Smithsonian Institution. 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-08-10. http://paleobiology.si.edu/paleoart/techniques/pages/reconstuct9.htm. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ^ "Materials Research Lab – Introduction to X-ray Diffraction". Materials Research Lab. University of Santa Barbara, California. 2011. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. http://www.mrl.ucsb.edu/mrl/centralfacilities/xray/xray-basics/index.html#x2. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.