- Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency

-

"CCVI" redirects here. For other uses, see CCVI (disambiguation).

Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency Classification and external resources

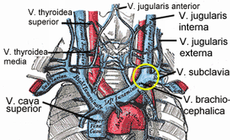

Veins of the neck. V.jugularis interna is stenosed or has a malformed valve that leads to CCSVI. The smaller veins that provide collateral circulation are visible in patients with CCSVI on the MRV investigationICD-10 I87.8 MeSH D014689 Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI or CCVI) is a term developed by Italian researcher Paolo Zamboni in 2008 to describe compromised flow of blood in the veins draining the central nervous system.[1][2] Zamboni hypothesized that it played a role in the cause of multiple sclerosis (MS).[3][4]

Zamboni also devised a procedure (Zamboni liberation procedure or Zamboni liberation therapy) involving angioplasty (or stenting) of certain veins in an attempt to improve blood flow.[5][6]

Within the medical community, both the procedure and CCSVI itself have been met with skepticism. Zamboni's first published research was neither blinded nor did it have a comparison group.[5] Research on CCSVI has been fast tracked but have been unable to confirm whether CCSVI has a role in causing MS.[7][8][9][10][11] The "liberation procedure" has been criticized for possibly resulting in serious complications and deaths while its benefits have not been proven.[5][6] This has raised serious objections to the hypothesis of CCSVI originating multiple sclerosis.[12] Additional research efforts investigating the CCSVI hypothesis are underway.

Contents

Consequences

Proposed consequences of CCSVI syndrome include intracranial hypoxia, delayed perfusion, reduced drainage of catabolites, increased transmural pressure,[13] and iron deposits around the cerebral veins.[14][15] Multiple sclerosis has been proposed as the main outcome of CCSVI.

Pathophysiology

Zamboni and colleagues claimed that in MS patients diagnosed with CCSVI, the azygos and IJV veins are stenotic in around 90% of the cases. Zamboni theorized that malformed blood vessels cause increased deposition of iron in the brain, which in turn triggers autoimmunity and degeneration of the nerve's myelin sheath.[14][16] While the initial article on CCSVI claimed that abnormal venous function parameters were not seen on healthy people others have noted that this is not the case.[16] In the report by Zamboni none of the healthy participants met criteria for a diagnosis of CCSVI while all patients did.[1][16] Such outstanding results have raised suspicions on a possible spectrum bias, which originates on a diagnostic test not being used under clinically significant conditions.[16]

In 2010 and 2011 further studies of the relationship between CCSVI and MS have had variable results.[8][9][10] As of September 2010 there were a growing number of papers that raise serious questions about its (CCSVI) validity",[12] although evidence had been "both for and against the controversial hypothesis".[17] It has been agreed that it is urgent to perform appropriate epidemiological studies to define the possible relationship between CCSVI and MS, while existing data does not support CCSVI as the cause of MS.[18] A randomised controlled study of 499 patients confirmed twice as big prevalence of CCSVI in MS patients in comparison with healthy controls, but this prevalence was also increased, to a lesser extent, in patients with other neurological diseases.[19] If there is a relationship between CCSVI and MS it is expected to be a complex one.[17]

Venous malformations

Most of the venous problems in MS patients have been reported to be truncular venous malformations, including azygous stenosis, defective jugular valves and jugular vein aneurysms. The innominate vein and superior vena cava have also been reported to contribute to CCSVI.[20] A vascular component in MS had been cited previously.[21][22]

Several characteristics of venous diseases make it difficult to include MS in such group.[12] In its current form, CCSVI cannot explain some of the epidemiological findings in MS. These include risk factors such as epstein-barr infection, parental ancestry, the day of birth and geographic location.[12][23] MS is also more common in women, while venous diseases are more common in men. Venous pathology is commonly associated to hypertension, infarcts, edema and transient ischemia, and occur more often with age, however they are hardly ever seen in MS and the disease is rare to appear after age 50. Finally, an organ-specific immune response is not seen in any other kind of venous disease.[12]

Iron deposits

Iron deposition as a cause of MS received support when a relation between venous pressure and iron depositions in MS patients was found in a neuroimaging study and criticism as other researchers found normal ferritin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients.[18][24] Additionally iron deposition occurs in different neurological diseases such as Alzheimer's disease or Parkinson's disease that are not associated with CCSVI.[1][16] Evidence linking CCSVI and iron deposition is lacking, and dysregulation of iron metabolism in MS is more complex than simply iron accumulation in the brain tissue.[25]

Genetics

A small genetic study looked at fifteen MS patients who also had CCSVI. It found 234 specific copy number variations in the human leucocitar antigen focus. Of these, GRB2, HSPA1L and HSPA1A were found to be specifically connected to both MS and angiogenesis, TAF11 was connected to both MS and artery passage, and HLA-DQA2 was suggestive of having an implication for angiogenesis as it interacts with CD4.[26] A study in 268 MS patients and 155 controls reported more than twice higher frequency of CCSVI in the MS group vs the controls group and also higher in the progressive MS group vs in the non-progressive MS group. This study found no relationship between CCSVI and HLA DRB1*1501, a genetic variation that has been consistently linked to MS.[27]

Diagnosis

Computer-enhanced transcranial doppler.

Computer-enhanced transcranial doppler.

CCSVI was first found using specialized extracranial and transcranial doppler sonography.[1][16] Five ultrasound criteria of venous drainage have been proposed to be characteristic of the syndrome, although having two of them is enough for diagnosis of CCSVI:[1][16][28]

- reflux in the internal jugular and vertebral veins,

- reflux in the deep cerebral veins,

- high-resolution B-mode ultrasound evidence of stenosis of the internal jugular vein,

- absence of flow in the internal jugular or vertebral veins on Doppler ultrasound, and

- reverted postural control of the main cerebral venous outflow pathways.

It is still not clear whether magnetic resonance venography, venous angiography, or Doppler sonography should be considered as the gold standard for the diagnosis of CCSVI.[18] Use of magnetic resonance venography for the diagnosis of CCSVI in MS patients has been proposed by some to have limited value, and to be used only in combination with other techniques.[29] Others have stated that magnetic resonance venography has advantages over doppler since results are more operator-independent.[10]

Currently plethysmography is under study for diagnosis[30]

Treatment

Balloon angioplasty and stenting have been proposed as a treatment option for CCSVI in MS. As a form of treatment, outside the trial setting, these procedures are not currently recommended.[3] The proposed treatment has been termed "liberation procedure" though the name has been criticized for suggesting unrealistic results.[12] As of 2011, angioplasty treatment for CCSVI is in phase III trials.[31]

Angioplasty in a preliminary study by Zamboni improved symptoms in MS.[32] High re-stenosing rates led authors of Zamboni's pilot study to propose that the use of stents might be a better treatment than balloons angioplasty,[16] while later they stated that stents should not be used.[33]

Further trials however are required to determine if the benefits, if any, of the procedure outweigh its risks.[16] The neurological community and many MS organizations such as the National Multiple Sclerosis Society of the USA recommend not to use the proposed treatment until its effectiveness is confirmed by controlled studies,[5][6][16][34] The Society of Interventional Radiology in USA and Canada considers that published literature on the effectiveness of CCSVI intervention is inconclusive and support decisions made by patients, families and physicians to perform angioplasty in such cases.[35] The Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe (CIRSE) position is that procedures for CCSVI should not be offered outside well designed clinical trials as harm could be caused.[36]

Kuwait has become the first country in the world where it is explicitly allowed by the medical authorities and paid by the state health system.[37] The procedure is being performed privately in 40 countries.[38] It is not available in Canada as of September 2010.[38]

Adverse effects

While the procedure has been reported to be in general safe for MS patients,[18][39] severe complications related to the angioplasty and stenting include intracranial hemorrhage, stent migration into the heart and jugular vein thrombosis.[12] Two cases with severe adverse events have been reported in the scientific literature; a death due to a cerebral hemorrhage while on anticoagulant following a stent insertion, and a migration of a stent to the heart's ventricle.[18] Some United States hospitals have banned the surgical procedure outside of clinical trials until more evidence to support its use is available.[6][40]

In 2010 Stanford University halted CCSVI treatments after two serious incidents. Dr Jeffrey Dunn, associate director of Stanford’s MS centre, called on other neurologists to speak out about the potential "dangers" of the unproven procedure: "If I can do anything to protect MS patients from the potentially devastating effects of false hopes or the risks of invasive and unproven treatment, I am happy to do so".[41]

Two Canadians have died after undergoing CCSVI treatment abroad.[42]

History

Venous pathology has been associated with MS for more than a century. Pathologist Georg Eduard Rindfleisch noted in 1863 that the inflammation-associated lesions were distributed around veins.[43]. Later, in 1935, Tracy Putnam was able to produce similar lesions in dogs blocking their veins[44]

The term "chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency" was coined in 2008 by Paolo Zamboni, who described it in patients with multiple sclerosis. According to Zamboni, CCSVI had a high sensitivity and specificity differentiating healthy individuals from those with multiple sclerosis.[1][16] Zamboni's results were criticized as his study was not blinded and they need to be verified by further studies.[1][16] A more detailed evidence of a correlation between the place and type of venous malformations imaged and the reported symptoms of multiple sclerosis in the same patients was published in 2010.[2]

The first international symposium took place in 2009, at Bologna.[45] Venous stenosis due to developmental abnormalities was established as the primary cause of CCSVI by the International Union of Phlebology[46] of which Zamboni is a member.[47] Another international conference was held in Glasgow on October 2010.[48][49]

Society and culture

The hypothesis has generated optimism from people with MS for more effective treatment options.

Media

CCSVI has received a lot of attention in all media, scientific literature and internet.[12] People with MS often read extensively on the CCSVI theory and its development on internet sites,[48] and a search for "liberation procedure" in Google yielded as of August 2010 more than 2.5 million hits.[12] Internet has also been used to make commercial advertisement of places where stenting for CCSVI is performed.[12]

Social media coverage has been perceived by some as "hype", with exaggerated claims that have led to excessive expectations.[5][50] This has been partially attributed to some of the same investigators of the theory.[5] Social media have also been accused of creating a division between CCSVI supporters and those who say it does not work, while a positive effect of the important media coverage may be that it forces the world of medical research to be self-critical and give appropriate responses to the questions that globalization of the theory raises, specially among MS sufferers.[50]

Many patients who have had the surgical procedure show their improvements on social media websites such as YouTube.[48] Such stories are anecdotal evidence of efficacy.[48] It has been pointed out that those who have had a positive result are more prone to post their case than those who had little or no improvement,[48] and the reported improvements in patients' condition can be attributed to the placebo effect.[50][51][52] Patients' reasons for not publishing negative results may include embarrassment about the money spent in the procedure without effect, or the negative reaction they expect from other people with MS.[50] Caution has been recommended regarding patients' self-reports found on the web.[48][50][51][53]

Research funding in Canada

Debate has been heated regarding funding of CCSVI research in Canada.[17]

In 2009, the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada committed to funding research on the connection between CCSVI and MS,[54] although later in 2010 it has come under criticism for opposing clinical trials of CCSVI therapy.[55] The MS Society of Canada in September 2010 reserved one million dollars toward CCSVI research "when a therapeutic trial is warranted and approved."[56]

At a political level there have been contradictory positions, with some provinces funding trials, others stating that since therapy is unproven they should wait,[57][58][59] and others urging for a pan-Canadian trial.[60] Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the federal agency responsible for funding health research, has recommended against funding a pan-Canadian trial of liberation therapy yet because "There is an overwhelming lack of scientific evidence on the safety and efficacy of the procedure, or even that there is any link between blocked veins and MS." It has suggested a scientific expert working group made up of the principal investigators for the seven MS Society-sponsored studies.[61] The health minister accepted the CIHR recommendation and has said that Canada will not fund a clinical trial at this time.[62]

Debate was further fueled by a report in the media that a former researcher in Saskatchewan proposed investigating a link between blood flow to the brain and MS in 1998.[63][64]

Research directions

There are further ongoing studies aiming to clarify if there is a relationship between MS and CCSVI using similar methods to Zamboni's initial study. A large ongoing study at Buffalo Neuroimaging Analysis Center has had preliminary results partially conflicting with those of Zamboni: while CCSVI was found in 62% of MS patients, it was also found in 26% of healthy controls and 45% of participants with other neurological disorders.[12][33] The US and Canadian MS societies have launched seven studies aiming to clarify the relationship between MS and CCSVI.[12][65] The CIRSE has stated that treatment research should begin by a small, placebo-controlled, prospective randomised trial which should be monitored by an independent organization.[36]

In June 2011, the Canadian federal government announced that they will fund clinical trials of Dr Zamboni's procedure to widen the veins [66] after a panel of scientific experts unanimously agreed that there is enough evidence to warrant the trial.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Zamboni P, Galeotti R, Menegatti E, et al. (April 2009). "Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency in patients with multiple sclerosis". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 80 (4): 392–9. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2008.157164. PMC 2647682. PMID 19060024. http://jnnp.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/80/4/392.

- ^ a b Bartolomei I. et al (April 2010). "Haemodynamic patterns in chronic cereblrospinal venous insufficiency in multiple sclerosis. Correlation of symptoms at onset and clinical course.". Int Angiol 29 (2): 183–8. PMID 20351667.

- ^ a b Khan O, Filippi M, Freedman MS, et al. (March 2010). "Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency and multiple sclerosis". Ann. Neurol. 67 (3): 286–90. doi:10.1002/ana.22001. PMID 20373339. "A chronic state of impaired venous drainage from the central nervous system, termed chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI), is claimed to be a pathologic phenomenon exclusively seen in multiple sclerosis (MS)."

- ^ Lee AB, Laredo J, Neville R (April 2010). "Embryological background of truncular venous malformation in the extracranial venous pathways as the cause of chronic cerebro spinal venous insufficiency". Int Angiol 29 (2): 95–108. PMID 20351665. "A similar condition involving the head and neck venous system may cause chronic cerebro-spinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI) and may be involved in the development or exacerbation of multiple sclerosis."

- ^ a b c d e f Qiu J (May 2010). "Venous abnormalities and multiple sclerosis: another breakthrough claim?". Lancet Neurol 9 (5): 464–5. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70098-3. PMID 20398855.

- ^ a b c d "Experimental multiple sclerosis vascular shunting procedure halted at Stanford". Ann. Neurol. 67 (1): A13–5. January 2010. doi:10.1002/ana.21969. PMID 20186848.

- ^ "Imaging studies challenge Zamboni theory of MS". Canadian Medical Association. http://www.cma.ca/index.php?ci_id=202821&la_id=1. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ a b Primary studies during 2010 on CCSVI and MS:

- Krogias C, Schröder A, Wiendl H, Hohlfeld R, Gold R (April 2010). "["Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency" and multiple sclerosis : Critical analysis and first observation in an unselected cohort of MS patients.]". Nervenarzt 81 (6): 740–6. doi:10.1007/s00115-010-2972-1. PMID 20386873.

- Sundström, P.; Wåhlin, A.; Ambarki, K.; Birgander, R.; Eklund, A.; Malm, J. (2010). "Venous and cerebrospinal fluid flow in multiple sclerosis: A case-control study". Annals of Neurology 68 (2): 255–259. doi:10.1002/ana.22132. PMID 20695018.

- Doepp F, Paul F, Valdueza JM, Schmierer K, Schreiber SJ (August 2010). "No cerebrocervical venous congestion in patients with multiple sclerosis". Ann Neurol 68 (2): 173–83. doi:10.1002/ana.22085. PMID 20695010.

- Al-Omari MH, Rousan LA (April 2010). "Internal jugular vein morphology and hemodynamics in patients with multiple sclerosis". Int Angiol 29 (2): 115–20. PMID 20351667.

- Yamout B, Herlopian A, Issa Z, et al. (November 2010). "Extracranial venous stenosis is an unlikely cause of multiple sclerosis". Mult. Scler. 16 (11): 1341–8. doi:10.1177/1352458510385268. PMID 21041329.

- ^ a b Primary studies during 2011 on CCSVI and MS:

- Mayer CA, Pfeilschifter W, Lorenz MW, et al. (February 2011). "The perfect crime? CCSVI not leaving a trace in MS". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 82 (4): 436–440. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.231613. PMC 3061048. PMID 21296899. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3061048.

- Baracchini C, Perini P, Calabrese M, Causin F, Rinaldi F, Gallo P (January 2011). "No evidence of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency at multiple sclerosis onset". Ann. Neurol. 69 (1): 90–9. doi:10.1002/ana.22228. PMID 21280079.

- Meyer-Schwickerath R, Haug C, Hacker A, et al. (January 2011). "Intracranial venous pressure is normal in patients with multiple sclerosis". Mult Scler. doi:10.1177/1352458510395982. PMID 21228026.

- Zivadinov R, Lopez-Soriano A, Weinstock-Guttman B, et al. (February 2011). "Use of MR Venography for Characterization of the Extracranial Venous System in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis and Healthy Control Subjects". Radiology 258 (2): 562–70. doi:10.1148/radiol.10101387. PMID 21177394.

- ^ a b c Wattjes MP, van Oosten BW, de Graaf WL, et al. (October 2010). "No association of abnormal cranial venous drainage with multiple sclerosis: a magnetic resonance venography and flow-quantification study". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 82 (4): 429–435. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.223479. PMID 20980483.

- ^ CCSVI study - results announced http://www.mssociety.org.uk/news_events/news/press_releases/ccsvi_news.html

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Dorne H, Zaidat OO, Fiorella D, Hirsch J, Prestigiacomo C, Albuquerque F, Tarr RW. (October 2010). "Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency and the doubtful promise of an endovascular treatment for multiple sclerosis". J NeuroIntervent Surg 2 (4): 309. doi:10.1136/jnis.2010.003947.

- ^ Franceschi C (April 2009). "The unsolved puzzle of multiple sclerosis and venous function". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 80 (4): 358. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2008.168179. PMID 19289474.

- ^ a b Singh AV, Zamboni P (December 2009). "Anomalous venous blood flow and iron deposition in multiple sclerosis". J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 29 (12): 1867–78. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2009.180. PMID 19724286.

- ^ Zamboni P (November 2006). "The big idea: iron-dependent inflammation in venous disease and proposed parallels in multiple sclerosis". J R Soc Med 99 (11): 589–93. doi:10.1258/jrsm.99.11.589. PMC 1633548. PMID 17082306. http://www.jrsm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17082306.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Khan O, Filippi M, Freedman MS, et al. (March 2010). "Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency and multiple sclerosis". Ann. Neurol. 67 (3): 286–90. doi:10.1002/ana.22001. PMID 20373339. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/123283159/abstract.

- ^ a b c Susan Jeffrey (2009-12-03). "CCSVI in Focus at ECTRIMS: New Data but Still Little Clarity". Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/732683. Retrieved 2010-11-23.

- ^ a b c d e Ghezzi A, Comi G, Federico A (December 2010). "Chronic cerebro-spinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI) and multiple sclerosis". Neurol Sci 32 (1): 17–21. doi:10.1007/s10072-010-0458-3. PMID 21161309.

- ^ Zivadinov R et al (April 2011). "Prevalence, sensitivity, and specificity of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency in MS". Neurology. PMID 21490322.

- ^ Lee AB, Laredo J, Neville R (April 2010). "Embryological background of truncular venous malformation in the extracranial venous pathways as the cause of chronic cerebro spinal venous insufficiency". Int Angiol 29 (2): 95–108. PMID 20351665. http://www.fondazionehilarescere.org/pdf/03-2518-ANGY.pdf.

- ^ Simka M (May 2009). "Blood brain barrier compromise with endothelial inflammation may lead to autoimmune loss of myelin during multiple sclerosis". Curr Neurovasc Res 6 (2): 132–9. doi:10.2174/156720209788185605. PMID 19442163.

- ^ Marrie RA, Rudick R, Horwitz R, et al. (March 2010). "Vascular comorbidity is associated with more rapid disability progression in multiple sclerosis". Neurology 74 (13): 1041–7. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d6b125. PMC 2848107. PMID 20350978. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2848107.

- ^ Handel AE, Lincoln MR, Ramagopalan SV (August 2010). "Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency and multiple sclerosis". Ann. Neurol. 68 (2): 270. doi:10.1002/ana.22067. PMID 20695021.

- ^ Primary studies during 2010 on neuroimaging, CCSVI, and MS:

- Worthington V, Killestein J, Eikelenboom MJ, et al. (November 2010). "Normal CSF ferritin levels in MS suggest against etiologic role of chronic venous insufficiency". Neurology 75 (18): 1617–22. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fb449e. PMID 20881272.

- Haacke EM, Garbern J, Miao Y, Habib C, Liu M. (April 2010). "Iron stores and cerebral veins in MS studied by susceptibility weighted imaging". Int Angiol 2 (2): 149–157. PMID 20351671.}

- ^ van Rensburg SJ, van Toorn R (November 2010). "The controversy of CCSVI and iron in multiple sclerosis: is ferritin the key?". Neurology 75 (18): 1581–2. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fb44f0. PMID 20881276.

- ^ Ferlini A, Bovolenta M, Neri M, Gualandi F, Balboni A, Yuryev A, Salvi F, Gemmati D, Liboni A, Zamboni P (2010-04-28). "Custom CGH array profiling of copy number variations (CNVs) on chromosome 6p21.32 (HLA locus) in patients with venous malformations associated with multiple sclerosis". BMC Med Genet 11: 64. doi:10.1186/1471-2350-11-64. PMC 2880319. PMID 20426824. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2880319. (primary source)

- ^ Weinstock-Guttman B, Zivadinov R, Cutter G, et al. (2011). Kleinschnitz, Christoph. ed. "Chronic Cerebrospinal Vascular Insufficiency Is Not Associated with HLA DRB1*1501 Status in Multiple Sclerosis Patients". PLoS ONE 6 (2): e16802. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016802. PMC 3038867. PMID 21340025. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3038867. (primary source)

- ^ Simka M, Kostecki J, Zaniewski M, Majewski E, Hartel M (April 2010). "Extracranial Doppler sonographic criteria of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency in the patients with multiple sclerosis". Int Angiol 29 (2): 109–14. PMID 20351666.

- ^ Hojnacki D, Zamboni P, Lopez-Soriano A, et al. (April 2010). "Use of neck magnetic resonance venography, Doppler sonography and selective venography for diagnosis of chronic y: a pilot study in multiple sclerosis patients and healthy controls". Int Angiol 29 (2): 127–39. PMID 20351669.

- ^ clinicaltrials.gov web site [1]

- ^ See clinicaltrials.gov[2]

- ^ Zamboni P, Galeotti R, Menegatti E, et al. (December 2009). "A prospective open-label study of endovascular treatment of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency". J. Vasc. Surg. 50 (6): 1348–58.e1–3. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2009.07.096. PMID 19958985.

- ^ a b Laino, Charlene (17 June 2010). "New Theory on CCSVI and MS Needs Further Study, Experts Say". Neurology Today. http://www.aan.com/elibrary/neurologytoday/?event=home.showArticle&id=ovid.com:/bib/ovftdb/00132985-201006170-00013. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ^ Susan Jeffrey (2009-12-03). "Endovascular Treatment of Cerebrospinal Venous Insufficiency Safe, May Provide Benefit in MS". Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/713367. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- ^ Vedantham, S; Benenati, JF; Kundu, S; Black, CM; Murphy, KJ; Cardella, JF; Society of Interventional Radiology; Canadian Interventional Radiology Association (2010). "Interventional endovascular management of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency in patients with multiple sclerosis: a position statement by the Society of Interventional Radiology, endorsed by the Canadian Interventional Radiology Association". Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR 21 (9): 1335–7. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2010.07.004. PMID 20800776.

- ^ a b Reekers JA, Lee MJ, Belli AM, Barkhof F (December 2010). "Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe Commentary on the Treatment of Chronic Cerebrospinal Venous Insufficiency". Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 34 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1007/s00270-010-0050-5. PMID 21136256.

- ^ Favaro, Avis (9 April 2010). "Kuwait to offer controversial MS treatment". CTV Winnipeg. http://winnipeg.ctv.ca/servlet/an/local/CTVNews/20100409/kuwait_ms_100409/20100409/?hub=WinnipegHome/. Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- ^ a b Melnychuk, Phil (16 September 2010). "Seeking liberation". Bclocalnews.com. http://www.bclocalnews.com/tri_city_maple_ridge/mapleridgenews/community/103094069.html/. Retrieved 2010-10-04.[dead link]

- ^ Ludyga T, Kazibudzki M, Simka M, et al. (2010). "Endovascular treatment for chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency: is the procedure safe?". Phlebology 25 (6): 286–95. doi:10.1258/phleb.2010.010053. PMID 21107001.

- ^ Siri Agrell (29 April 2010). "Legal fears thwart doctor's bid for ‘liberation' from MS pain". The Globe and Mail (Toronto). http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/legal-fears-thwart-doctors-bid-for-liberation-from-ms-pain/article1550377/. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- ^ "Stanford University halts CCSVI treatments after two serious incidents"http://www.mssociety.org.uk/news_events/news/press_releases/ccsvi.html

- ^ "2nd Canadian dies after MS surgery"http://www.cbc.ca/news/health/story/2011/07/08/multiple-sclerosis-ccsvi-death.html

- ^ Lassmann H (July 2005). "Multiple sclerosis pathology: evolution of pathogenetic concepts". Brain Pathology 15 (3): 217–22. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2005.tb00523.x. PMID 16196388.[verification needed]

- ^ Putnam, T. (1935). "Encephalitis and sclerotic plaques produced by venular obstruction". Arch Neurol Psychiatry;33(5):929-940. http://archneurpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/summary/33/5/929.

- ^ Rossini, F (2009-09-08). "Venous Function And Multiple Sclerosis" (doc). Fondazione Hilarescere. http://www.fondazionehilarescere.org/cst/eng/090908/1_CSTgenerale_8sett09_eng.doc. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ Lee BB, Bergan J, Gloviczki P, et al. (December 2009). "Diagnosis and treatment of venous malformations Consensus Document of the International Union of Phlebology (IUP)-2009". Int Angiol 28 (6): 434–51. PMID 20087280.

- ^ http://www.ctv.ca/CTVNews/WFive/20100127/ms_treatment_100127/

- ^ a b c d e f Tim Locke (12 October 2010). "CCSVI for MS in the UK". WebMD Health News (WebMD UK Limited and Boots UK Limited). http://www.webmd.boots.com/news/20101012/ccsvi-for-ms-in-the-uk?print=true. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ^ http://www.ms-ccsvi-uk.org/home/files/ms-ccsvi-uk/newsletter2010-11.pdf

- ^ a b c d e Jodie Sinemma (10 August 2010). "MS therapy divides even sufferers, as social media drives hype". Calgary Herald. http://www.calgaryherald.com/health/therapy+divides+even+sufferers+social+media+drives+hype/3383016/story.html. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- ^ a b "Information Sheet on Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and "Chronic Cerebrospinal Venous Insufficiency" (CCSVI)". Alberta Health Services. 6 August 2010. http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/feat/ne-feat-ccsvi-ms-info-sheet.pdf. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- ^ Pamela Cowan (6 August 2010). "'Placebo effect' a concern with controversial MS treatment: Experts". http://www.ottawacitizen.com/health/Placebo+effect+concern+with+controversial+treatment+Experts/3367299/story.html?cid=megadrop_story. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- ^ "Chronic Cerebrospinal Venous Insufficiency In Multiple Sclerosis (CCSVI-MS) , Between The Phantom Hope Of Miraculous Endovascular Treatment And The Truth Of The Need For More Radical Treatment.". Internet Scientific Publications. 14 january 2011. http://www.ispub.com/journal/the_internet_journal_of_interventional_medicine/volume_1_number_1_77/article/chronic-cerebrospinal-venous-insufficiency-in-multiple-sclerosis-ccsvi-ms-between-the-phantom-hope-of-miraculous-endovascular-treatment-and-the-truth-of-the-need-for-more-radical-treatment.html. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- ^ Picard, A (2009-11-23). "MS group to fund research into 'liberation procedure'". The Globe and Mail (Toronto). http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/ms-group-to-fund-research-into-liberation-procedure/article1374954/. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ "MS Society’s stand sparks resignation". The Telegram. 2010-09-01. http://www.thetelegram.com/News/Local/2010-09-01/article-1716828/MS-Society%26rsquo%3Bs-stand-sparks-resignation/1. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ "MS Society sets aside $1M in case CCSVI patient trial developed and approved". CBC News. 2010-09-16. http://www.cbc.ca/cp/health/TG3929.html. Retrieved 2010-09-18.[dead link]

- ^ O. Mansour, F. Talaat, A. Deef, A. Essa, M. Schumacher, L. Caplan, M. Mahdy (January 2011). "Chronic Cerebrospinal Venous Insufficiency In Multiple Sclerosis (CCSVI-MS) , Between The Phantom Hope Of Miraculous Endovascular Treatment And The Truth Of The Need For More Radical Treatment". Internet Journal of Interventional Medicine 1 (1): 186–201. http://www.ispub.com/journal/the_internet_journal_of_interventional_medicine/volume_1_number_1_77/article/chronic-cerebrospinal-venous-insufficiency-in-multiple-sclerosis-ccsvi-ms-between-the-phantom-hope-of-miraculous-endovascular-treatment-and-the-truth-of-the-need-for-more-radical-treatment.html.

- ^ Breakenridge R (2010-08-04). "Premiers jump the gun on MS treatment". Calgary Herald. http://www.calgaryherald.com/life/Premiers+jump+treatment/3356742/story.html.

- ^ "Premiers to debate MS treatment". CBC News. 2010-08-02. http://www.cbc.ca/health/story/2010/08/02/pei-ms-treatment-584.html.

- ^ "MS therapy trial urged by Manitoba minister". CBC News. Canadian Press. 2010-08-16. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/manitoba/story/2010/08/16/man-liberation-ms-clinical-trial.html.

- ^ "CIHR makes recommendations on Canadian MS research priorities". Canadian Institutes of Health Research. 2010-08-31. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/42382.html. Retrieved 2010-12-09.

- ^ "Health minister rejects MS therapy trial". CBC News. 2010-09-02. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/newfoundland-labrador/story/2010/09/01/ms-ccsvi-liberation-aglukkaq.html.

- ^ Juurlink BH (October 1998). "The multiple sclerosis lesion: initiated by a localized hypoperfusion in a central nervous system where mechanisms allowing leukocyte infiltration are readily upregulated?". Med. Hypotheses 51 (4): 299–303. doi:10.1016/S0306-9877(98)90052-4. PMID 9824835.

- ^ "Start MS trials now, says ex-U of S prof". The StarPhoenix. 28 August 2010. http://www.thestarphoenix.com/health/Start+trials+says+prof/3453385/story.html. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ CCSVI - current studies http://www.mssociety.org.uk/research/az_of_ms_research/cd/ccsvi_studies.html

- ^ Ottawa to fund clinical trials for controversial MS treatment

Further reading

- Rhodes, Marie A. (Author), Haacke, Mark E. (Foreword), Moore, Elaine A. (Series Editor, McFarland Health Topics) "CCSVI as the Cause of Multiple Sclerosis: The Science Behind the Controversial Theory"

Categories:- Vascular diseases

- Multiple sclerosis

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.