- Japanese American

-

Japanese Americans

日系アメリカ人(日系米国人)

Nikkei Americajin(Nikkei Beikokujin)

From top-left to bottom-right: Ellison Onizuka · Patsy Mink · Eric Shinseki

Yoko Ono · Sadao Munemori · Daniel Inouye

Kristi Yamaguchi · Norman Mineta · Ted Fujita

George Takei · Bryan Clay · Masi OkaTotal population 1,200,922

0.3% of the US population (2007)[1]Regions with significant populations West Coast, Hawaii, Northeast Languages American English, Japanese

Religion Japanese Americans (日系米国人 Nikkei Beikokujin) are American people of Japanese heritage. Japanese Americans have historically been among the three largest Asian American communities, but in recent decades have become the sixth largest group at roughly 1,204,205, including those of mixed-race or mixed-ethnicity. In the 2000 census, the largest Japanese American communities were in California with 394,896, Hawaii with 296,674, Washington with 56,210, New York with 45,237, and Illinois with 27,702.

Contents

Cultural profile

Generations

The nomenclature for each of their generations who are citizens or long-term residents of countries other than Japan, used by Japanese Americans and other nationals of Japanese descent are explained here; they are formed by combining one of the Japanese numbers corresponding to the generation with the Japanese word for generation (sei 世). The Japanese-American communities have themselves distinguished their members with terms like Issei, Nisei, and Sansei which describe the first, second and third generation of immigrants. The fourth generation is called Yonsei (四世) and the fifth is called Gosei (五世). The term Nikkei (日系) was coined by Japanese American sociologists and encompasses Japanese immigrants in all countries and of all generations.

Generation Summary Issei (一世) The generation of people born in Japan who later immigrated to another country. Nisei (二世) The generation of people born in North America, Latin America, Hawaii, or any country outside of Japan either to at least one Issei or one non-immigrant Japanese parent. Sansei (三世) The generation of people born in North America, Latin America, Hawaii, or any country outside of Japan to at least one Nisei parent. Yonsei (四世) The generation of people born in North America, Latin America, Hawaii, or any country outside of Japan to at least one Sansei parent. Gosei (五世) The generation of people born in North America, Latin America, Hawaii, or any country outside of Japan to at least one Yonsei parent. The kanreki (還暦), a pre-modern Japanese rite of passage to old age at 60, is now being celebrated by increasing numbers of Japanese-American Nisei. Rituals are enactments of shared meanings, norms, and values; and this traditional Japanese rite of passage highlights a collective response among the Nisei to the conventional dilemmas of growing older.[3]

Languages

Issei and many Nisei speak Japanese in addition to English as a second language. In general, later generations of Japanese Americans speak English as their first language, though some do learn Japanese later as a second language. In Hawaii however, where Nisei are about one-fifth of the whole population, Japanese is a major language, spoken and studied by many of the state's residents across ethnicities[citation needed]. It is taught in private Japanese language schools as early as the second grade. As a courtesy to the large number of Japanese tourists (from Japan), Japanese subtexts are provided on place signs, public transportation, and civic facilities. The Hawaii media market has a few locally produced Japanese language newspapers and magazines, however these are on the verge of dying out, due to a lack of interest on the part of the local (Hawaii-born) Japanese population. Stores that cater to the tourist industry often have Japanese-speaking personnel. To show their allegiance to the U.S., many Nisei and Sansei intentionally avoided learning Japanese. But as many of the later generations find their identities in both Japan and America, studying Japanese is becoming more popular than it once was.

Education

Japanese American culture places great value on education. Across generations, children are instilled with a strong desire to enter the rigors of higher education. Because of such widespread ambition among members of the Japanese-American community, math and reading scores on the SAT and ACT may often exceed the national averages. Japanese-Americans have the largest showing of any ethnic group in nationwide Advanced Placement testing each year.[citation needed]

A large majority of Japanese Americans obtain post-secondary degrees. Japanese Americans often face the "model minority" stereotype that they are dominant in math- and science-related fields in colleges and universities across the United States. In reality, however, there is an equal distribution of Japanese-Americans between the arts and humanities and the sciences.[citation needed] Although their numbers have declined slightly in recent years, Japanese Americans are still a prominent presence in Ivy League schools, the top University of California campuses including UC Berkeley and UCLA, and other elite universities.[citation needed] As subsequent generations of Japanese Americans have essentially become more "Americanized" they are not as cutthroat as other East Asian groups when it comes to aiming for admission to prestigious universities, but many are still ambitious and strive to attend the best universities in America.[citation needed]

Intermarriage

Before the 1960s, the trend of Japanese Americans marrying partners outside their racial or ethnic group was generally low, as well a great many traditional Issei parents encouraged Nisei to marry only within their ethnic/cultural group. Arrangements to purchase and invite picture brides from Japan to relocate and marry Issei or Nisei males was commonplace.[citation needed]

In California and other western states until the end of World War II, there were attempts to make it illegal for Japanese and other Asian Americans to marry European Americans, but those laws were declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court, like the anti-miscegenation laws which prevented European Americans from marrying African Americans in the 1960s.

According to a 1990 statistical survey by the Japan Society of America, the Sansei or third generations have an estimated 20 to 30 percent out-of-group marriage, while the 4th generation or Yonsei approaches nearly 50 percent. The rate for Japanese American women to marry European American and other Asian American men is becoming more frequent, but lower rates for Hispanic and American Indian men (although the number of Cherokee Indians in California with Japanese ancestry is much reported), and with African American men is even smaller.

During the WWII Internment era, the U.S. Executive Order 9066 had an inclusion of orphaned infants with "one drop of Japanese blood" (as explained in a letter by one official) or the order stated anyone at least one-sixteenth Japanese (descended from any intermarriage) lends credence to the argument that the measures were racially motivated, rather than a military necessity.

There were sizable numbers of Korean-Japanese, Chinese-Japanese, Filipino-Japanese, Mexican-Japanese, Native Hawaiian-Japanese and Cherokee-Japanese in California according to the 1940 U.S. Census who were eligible for internment as "Japanese" to indicate the first stage of widespread intermarriage of Japanese Americans, including those who passed as "white" or half-Asian/European.

Religion

Japanese Americans practice a wide range of religions, including Mahayana Buddhism (Jodo Shinshu, Jodo Shu, Nichiren, Shingon and Zen forms being most prominent) their majority faith, Shinto, and Christianity. In many ways, due to the longstanding nature of Buddhist and Shinto practices in Japanese society, many of the cultural values and traditions commonly associated with Japanese tradition have been strongly influenced by these religious forms.

A large number of the Japanese American community continue to practice Buddhism in some form, and a number of community traditions and festivals continue to center around Buddhist institutions. For example, one of the most popular community festivals is the annual Obon Festival, which occurs in the summer, and provides an opportunity to reconnect with their customs and traditions and to pass these traditions and customs to the young. These kinds of festivals are most popular in communities with large populations of Japanese Americans, such as in southern California or Hawaii. It should be noted however, that a reasonable number of Japanese people both in and out of Japan are secular, as Shinto and Buddhism are most often practiced by rituals such as marriages or funerals, and not through faithful worship, as defines religion for many Americans.

Celebrations

Japanese American celebrations tend to be more sectarian in nature and focus on the community-sharing aspects. An important annual festival for Japanese Americans is the Obon Festival, which happens in July or August of each year. Across the country, Japanese Americans gather on fair grounds, churches and large civic parking lots and commemorate the memory of their ancestors and their families through folk dances and food. Carnival booths are usually set up so Japanese American children have the opportunity to play together.

Major Celebrations in the United States Date Name Region January 1 Shōgatsu New Year's Celebration Nationwide February Japanese Heritage Fair Honolulu, HI February to March Cherry Blossom Festival Honolulu, HI March 3 Hina Matsuri (Girls' Day) Hawaii March Honolulu Festival Honolulu, HI March Hawaiʻi International Taiko Festival Honolulu, HI March International Cherry Blossom Festival Macon, GA March to April National Cherry Blossom Festival Washington, DC April Northern California Cherry Blossom Festival San Francisco, CA April Pasadena Cherry Blossom Festival Pasadena, CA April Seattle Cherry Blossom Festival Seattle, WA May 5 Tango no Sekku (Boys' Day) Hawaii May Shinnyo-En Toro-Nagashi (Memorial Day Floating Lantern Ceremony) Honolulu, HI June Pan-Pacific Festival Matsuri in Hawaiʻi Honolulu, HI July 7 Tanabata Festival Nationwide July–August Obon Festival Nationwide August Nihonmachi Street Fair San Francisco, CA August Nisei Week Los Angeles, CA History

Main article: Japanese American historyAlthough Japanese castaways such as Oguri Jukichi[4] and Otokichi[5] are known to have reached the Americas by at least the early 19th century, the history of Japanese Americans begins in the mid nineteenth century.

- 1841, June 27 Captain Whitfield, commanding a New England sailing vessel, rescues five shipwrecked Japanese sailors. Four disembark at Honolulu, however Manjiro Nakahama stays on board returning with Whitfield to Fairhaven, Massachusetts. After attending school in New England and adopting the name John Manjiro, he later became an interpreter for Commodore Matthew Perry.

- 1850. Seventeen survivors of a Japanese shipwreck are saved by the American freighter Auckland off the coast of California. In 1852, the group is sent to Macau to join Commodore Matthew C. Perry as a gesture to help open diplomatic relations with Japan. One of them, Joseph Heco (Hikozo Hamada), goes on to become the first Japanese person to become a naturalized American citizen.

- 1855: On February 8, the first official intake of Japanese migrants to a U.S.-controlled entity occurs when 676 men, 159 women, and 108 children arrive in Honolulu on board the Pacific Mail passenger freighter City of Tokio. These immigrants, the first of many Japanese immigrants to Hawaii, have come to work as laborers on the island's sugar plantations via an assisted passage scheme organized by the Hawaiian government .

- 1861: The utopian minister Thomas Lake Harris of the Brotherhood of the New Life visits England, where he meets Nagasawa Kanaye, who becomes a convert. Nagasawa returns to the U.S. with Harris and follows him to Fountaingrove in Santa Rosa, California. When Harris leaves the Californian commune, Nagasawa became the leader and remained there until his death in 1932.

- 1869: A group of Japanese people arrive at Gold Hills, California and build the Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Colony. Okei becomes the first recorded Japanese woman to die and be buried in the United States.

- 1885: The first wave of Japanese immigrants arrives to provide labor in Hawaiʻi sugarcane and pineapple plantations and California fruit and produce farms.

- 1893: The San Francisco Board of Education attempts to introduce segregation for Japanese American children, but withdraws the measure following protests by the Japanese government.

- 1900s: Japanese immigrants begin to lease land and sharecrop.

- 1902: Yone Noguchi publishes The American Diary of a Japanese Girl, the first Japanese American novel.

- 1906: The San Francisco Board of Education successfully implements segregation for Asian students in public schools.[citation needed]

- 1907: Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907 between United States and Japan results in Japan ending the issuance passports for new laborers.

- 1908: Japanese "picture brides" enter the United States.

- 1913: The California Alien Land Law of 1913 bans Japanese from purchasing land; whites threatened by Japanese success in independent farming ventures.

- 1924: The federal Immigration Act of 1924 banned immigration from Japan.

- 1930s: Issei become economically stable for the first time in California and Hawaiʻi.

- 1941: Attack on Pearl Harbor: Japanese forces attack the United States Navy base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu. Japanese community leaders are arrested and detained by federal authorities.

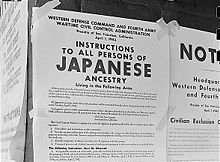

- 1942: President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066 on February 19, beginning Japanese-American internment. Over the course of the war, approximately 110,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese who lived on the West Coast of the United States are uprooted from their homes and interned.

- 1943: Japanese American soldiers from Hawaiʻi join the 100th Infantry Battalion of the United States Army. The battalion fights in Europe.

- 1944: Ben Kuroki became the only Japanese-American in the U.S. Army Air Force to serve in combat operations in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II.

- 1944: U.S. Army 100th Battalion merges with the all-volunteer Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

- 1945: By war's end, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team is awarded 18,143 decorations, including 9,486 Purple Hearts, becoming the most decorated military unit in United States history.

- 1959: Daniel K. Inouye is elected to the United States House of Representatives, becoming becomes the first Japanese American to serve in Congress.

- 1962: Minoru Yamasaki is awarded the contract to design the World Trade Center, becoming the first Japanese American architect to design a supertall skyscraper in the United States.

- 1963: Daniel K. Inouye becomes the first Japanese American in the United States Senate.

- 1965: Patsy T. Mink becomes the first woman of color in Congress.

- 1971: Norman Y. Mineta is elected mayor of San Jose, California, becoming the first Asian American mayor of a major U.S. city.

- 1972: Robert A. Nakamura produces Manzanar, the first personal documentary about internment.

- 1974: George R. Ariyoshi becomes the first Japanese American governor in the State of Hawaiʻi.

- 1976: S. I. Hayakawa of California and Spark Matsunaga of Hawaiʻi become the second and third U.S. Senators of Japanese descent.

- 1978: Ellison S. Onizuka becomes the first Asian American astronaut. Onizuka was one of the seven astronauts to die in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986.

- 1980: Congress creates the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians to investigate internment during World War II.

- 1983: The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians reports that Japanese-American internment was not justified by military necessity and that internment was based on "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership." The Commission recommends an official Government apology; redress payments of $20,000 to each of the survivors; and a public education fund to help ensure that this would not happen again.

- 1988: President Ronald Reagan signs the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, apologizing for Japanese-American internment and providing reparations of $20,000 to each victim.

- 1994: Mazie K. Hirono is elected Lieutenant Governor of Hawaii, becoming the first Japanese immigrant elected state lieutenant governor of a state. Hirono later is elected in the U.S. House of Representatives.

- 1996: A. Wallace Tashima is nominated to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and becomes the first Japanese American to serve as a judge of a United States court of appeals.

- 1998: Chris Tashima becomes the first U.S.-born Japanese American actor to win an Academy Award for his role in the film Visas and Virtue.

- 1999: U.S. Army General Eric Shinseki becomes the first Asian American to serve as chief of staff of a branch of the armed forces. Shinseki later serves as Secretary of Veterans Affairs.

- 2000, Norman Y. Mineta becomes the first Asian American appointed to the United States Cabinet. He serves as Secretary of Commerce from 2000–2001 and Secretary of Transportation from 2001–2006.

- 2010: Daniel K. Inouye becomes the highest ranking Asian American politician in U.S. history when he succeeds Robert Byrd as President pro tempore of the United States Senate.

Immigration

People from Japan began migrating to the U.S. in significant numbers following the political, cultural, and social changes stemming from the 1868 Meiji Restoration. Particularly after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, Japanese immigrants were sought by industrialists to replace the Chinese immigrants. In 1907, the "Gentlemen's Agreement" between the governments of Japan and the U.S. ended immigration of Japanese workers (i.e., men), but permitted the immigration of spouses of Japanese immigrants already in the U.S. The Immigration Act of 1924 banned the immigration of all but a token few Japanese.

The ban on immigration produced unusually well-defined generational groups within the Japanese American community. Initially, there was an immigrant generation, the Issei, and their U.S.-born children, the Nisei Japanese American. The Issei were exclusively those who had immigrated before 1924. Because no new immigrants were permitted, all Japanese Americans born after 1924 were—by definition—born in the U.S. This generation, the Nisei, became a distinct cohort from the Issei generation in terms of age, citizenship, and English language ability, in addition to the usual generational differences. Institutional and interpersonal racism led many of the Nisei to marry other Nisei, resulting in a third distinct generation of Japanese Americans, the Sansei. Significant Japanese immigration did not occur until the Immigration Act of 1965 ended 40 years of bans against immigration from Japan and other countries.

The Naturalization Act of 1790 restricted naturalized U.S. citizenship to "free white persons," which excluded the Issei from citizenship. As a result, the Issei were unable to vote, and faced additional restrictions such as the inability to own land under many state laws.

Japanese Americans were parties in several important Supreme Court decisions, including Ozawa v. United States (1922) and Korematsu v. United States (1943). Korematsu is the origin of the "strict scrutiny" standard, which is applied, with great controversy, in government considerations of race since the 1989 Adarand Constructors v. Peña decision.

In recent years, immigration from Japan has been more like that from Western Europe: low and usually related to marriages between U.S. citizens and Japanese, with some via employment preferences. The number is on average 5 to 10 thousand per year, and is similar to the amount of immigration to the U.S. from Germany. This is in stark contrast to the rest of Asia, where family reunification is the primary impetus for immigration. Japanese Americans also have the oldest demographic structure of any non-white ethnic group in the U.S.; in addition, in the younger generations, due to intermarriage with whites and other Asian groups, part-Japanese are more common than full Japanese, and it appears as if this physical assimilation will continue at a rapid rate.

Internment

Main article: Japanese-American internmentDuring World War II, an estimated 120,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals or citizens residing in the United States were forcibly interned in ten different camps across the US, mostly in the west. The internments were based on the race or ancestry rather than activities of the interned. Families, including children, were interned together. Each member of the family was allowed to bring two suitcases of their belongings. Each family, regardless of its size, was given one room to live in. The camps were fenced in and patrolled by armed guards.

For the most part, the internees remained in the camps until the end of the war, when they left the camps to rebuild their lives. Several Japanese Americans began lawsuits against the U.S. government for wrongful internment, which culminated, decades later, in the 1980s, in official apologies and reparations of over $1.2 billion. Because many of the internees were no longer alive to receive those reparations, the money was paid to their heirs. To commemorate the life of Fred Korematsu, a civil rights activist, most known for the United States Supreme Court case, Korematsu v. United States (1944), which challenged the order sending Japanese Americans into internment camps during World War II, the "Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution" was observed for first time on January 30, 2011, by the state of California, and first such commemoration for an Asian American in the US.[6][7][8]

World War II Service

Main article: Japanese American service in World War IIMany Japanese Americans served with great distinction during World War II in the American forces.

Nebraska Nisei Ben Kuroki became a famous Japanese-American soldier of the war after he completed 30 missions as a gunner on B-24 Liberators with the 93rd Bombardment Group in Europe. When he returned to the US he was interviewed on radio and made numerous public appearances, including one at San Francisco's Commonwealth Club where he was given a ten-minute standing ovation after his speech. Kuroki's acceptance by the California businessmen was the turning point in attitudes toward Japanese on the West Coast. Kuroki volunteered to fly on a B-29 crew against his parent's homeland and was the only Nisei to fly missions over Japan. He was awarded a belated Distinguished Service Medal by President George W. Bush in August 2005.

The 442nd Regimental Combat Team/100th Infantry Battalion is one of the most highly decorated unit in U.S. military history. Composed of Japanese Americans, the 442nd/100th fought valiantly in the European Theater. The 522nd Nisei Field Artillery Battalion was one of the first units to liberate the prisoners of the Nazi concentration camp at Dachau. Hawaiʻi Senator Daniel Inouye is a veteran of the 442nd. Additionally the Military Intelligence Service consisted of Japanese Americans who served in the Pacific Front.

On October 5, 2010, the Congressional Gold Medal was awarded to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the 100th Infantry Battalion, as well as the 6,000 Japanese Americans who served in the Military Intelligence Service during the war.[9]

Redress

Main article: Japanese American redress and court casesIn the U.S., the right to redress is defined as a constitutional right, as it is decreed in the First Amendment to the Constitution.

Redress may be defined as follows:

- 1. the setting right of what is wrong: redress of abuses.

- 2. relief from wrong or injury.

- 3. compensation or satisfaction from a wrong or injury

Reparation is defined as:

- 1. the making of amends for wrong or injury done: reparation for an injustice.

- 2. Usually, reparations. compensation in money, material, labor, etc., payable by a defeated country to another country or to an individual for loss suffered during or as a result of war.

- 3. restoration to good condition.

- 4. repair. (“Legacies of Incarceration,” 2002)

The campaign for redress against internment was launched by Japanese Americans in 1978. The Japanese American Citizens’ League (JACL) asked for three measures to be taken as redress: $25,000 to be awarded to each person who was detained, an apology from Congress acknowledging publicly that the U.S. government had been wrong, and the release of funds to set up an educational foundation for the children of Japanese American families. Under the 2001 budget of the United States, it was also decreed that the ten sites on which the detainee camps were set up are to be preserved as historical landmarks: “places like Manzanar, Tule Lake, Heart Mountain, Topaz, Amache, Jerome, and Rohwer will forever stand as reminders that this nation failed in its most sacred duty to protect its citizens against prejudice, greed, and political expediency” (Tateishi and Yoshino 2000). Each of these concentration camps was surrounded by barbed wire and contained at least ten thousand forced detainees.

Life under United States policies before and after World War II

Main articles: Japanese American life before World War II and Japanese American life after World War IILike most of the American population, Japanese immigrants came to the U.S. in search of a better life. Some planned to stay and build families in the United States, while others wanted to save money from working stateside to better themselves in the country from which they had come. Before the Attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese residents experienced a moderate level of hardship that was fairly typical for any minority group at the time.

Farming

Japanese Americans have made significant contributions to the agriculture of the western United States, particularly in California and Hawaii. Nineteenth century Japanese immigrants introduced sophisticated irrigation methods that enabled the cultivation of fruits, vegetables, and flowers on previously marginal lands.

While the Issei (1st generation Japanese Americans) prospered in the early 20th century, most lost their farms during the internment. Although this was the case, Japanese Americans remain involved in these industries today, particularly in southern California and to some extent, Arizona by the areas' year-round agricultural economy, and descendants of Japanese pickers who adapted farming in Oregon and Washington state.

Japanese American detainees irrigated and cultivated lands near World War II internment camps, which were located in desolate spots such as Poston, in the Arizona desert, and Tule Lake, California, at a dry mountain lake bed. Due to their tenacious efforts, these farm lands remain productive today.

Politics

See also: Anti-Japanese sentimentJapanese Americans have shown strong support for candidates in both political parties. Shortly prior to the 2004 U.S. presidential election, Japanese Americans narrowly favored Democrat John Kerry by a 42% to 38% margin over Republican George W. Bush.[10]

Neighborhoods and communities

See also: JapantownThe West Coast

- Southern California has sporadic Japanese American communities:

- Los Angeles, includes the Little Tokyo section.

- Anaheim and Orange County.

- Fontana in the Inland Empire.

- Gardena in Los Angeles' South Bay area.

- Long Beach, California - historic Japanese fisheries presence in Terminal Island.

- Pasadena in the Los Angeles' San Gabriel Valley.

- Palm Desert, also the Japanese developed the year-round agricultural industries in the Coachella Valley and Imperial Valley.

- Sawtelle, California, in West Los Angeles.

- Torrance in Los Angeles' South Bay area.

- Ventura County.

- Central Valley, California region:

- Bakersfield/ Kern County, California.

- Fresno - 5% of the county have Japanese ancestry.

- Merced.

- Stockton.

- Butte County.

- Sutter County.

- San Francisco Bay Area, the main concentration of Nisei and Sansei in the 20th century:

- Alameda County - concentrated and historic populations in the cities of Alameda, Berkeley, Fremont, Oakland, and Hayward.

- Contra Costa County - concentrated in Walnut Creek

- San Mateo County esp. Daly City and Pacifica.

- San Jose, has one of the three remaining officially recognized Japantowns in North America.

- Santa Clara County - concentrated in Cupertino, Palo Alto, Santa Clara, and Sunnyvale

- San Francisco, notably in the Japantown district, the largest Japanese community in North America. [11]

- Santa Cruz County

- Hawaii, where a quarter of the population is of Japanese descent.

- Monterey County, especially Salinas, California.

- Sacramento and the neighborhoods of Florin and Walnut Grove.

- San Diego area:

- La Jolla, San Diego.

- Bonsall east of Oceanside.

- Japanese community center in Vista in North County one of two of its kind in Southern California.

- San Luis Obispo.

- Santa Barbara.

- Seattle area.

- Bellevue.

- Redmond.

- Tacoma.

- Puget Sound region (San Juan Islands) have Japanese fisheries for over a century.

- Skagit Valley of Washington.

- Yakima Valley, Washington.

- Chehalis Valley of Washington.

- Portland, Oregon and surrounding area.

- Willamette Valley, Oregon.

- Phoenix Area notably a section of Grand Avenue in Northwest Phoenix, and Maryvale (Phoenix).

- Las Vegas Area with a reference of Japanese farmers on Bonzai Slough, Arizona near Needles, California.

- Southern Arizona, part of the "exclusion area" for Japanese internment during World War II along with the Pacific coast states.

- Yuma County, Arizona.

Outside the west coast

- Arlington, Virginia and Alexandria, Virginia (the Northern Virginia region).

- Bergen County, New Jersey.

- Boise, Idaho.

- Boston, Massachusetts.

- Chicago, Illinois and suburbs:

- Arlington Heights, Illinois.

- Buffalo Grove, Illinois.

- Evanston, Illinois.

- Elk Grove Heights, Illinois and nearby Elk Grove Village, Illinois.

- Kane County, Illinois.

- Naperville, Illinois.

- Schaumburg, Illinois.

- Skokie, Illinois.

- Wilmette, Illinois.

- Denver, Colorado, note Sakura Square.

- Gallup, New Mexico, in World War II the city fought to prevent the internment of its 800 Japanese residents.

- Grand Prairie, Texas and Arlington, Texas (the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex area).

- Greeley, Colorado.

- Houston, Texas.

- McAllen, Texas.

- Miami, Florida.

- Mobile, Alabama.

- New York City, New York - According to the Japanese Embassy of the USA, over 100,000 persons of Japanese ancestry live in the NYC metro area, including South Shore (Long Island) and Hudson Valley; Fairfield County, Connecticut and Northern New Jersey.

- Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

- Orlando, Florida.

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania with the suburbs of Chester County, Pennsylvania.

- Salem, New Jersey and Cherry Hill, New Jersey (see Delaware Valley).

- Salt Lake City, Utah.

- Washington, DC.

- Wilmington, Delaware.

- Wilmington, North Carolina.

Notable individuals

See also: List of Japanese AmericansPolitics

After the Territory of Hawaiʻi's statehood in 1959, Japanese American political empowerment took a step forward with the election of Daniel K. Inouye to Congress. In 2010, Inouye was sworn in as President Pro Tempore making him the highest-ranking Asian-American politician in American history. Spark Matsunaga was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1963, and in 1965 Patsy Mink became the first Asian American woman elected to the United States Congress.

Inouye, Matsunaga, and Mink's success led to the gradual acceptance of Japanese American leadership on the national stage, culminating in the appointments of Eric Shinseki and Norman Y. Mineta, the first Japanese American military chief of staff and federal cabinet secretary, respectively.

Japanese American members of the United States House of Representatives have included Daniel K. Inouye, Spark Matsunaga, Patsy Mink, Norman Mineta, Bob Matsui, Pat Saiki, Mike Honda, Doris Matsui, and Mazie Hirono. Japanese American members of the United States Senate have included Daniel K. Inouye, Samuel I. Hayakawa, and Spark Matsunaga.

George Ariyoshi served as the Governor of Hawaiʻi from 1974 to 1986. He was the first American of Asian descent to be elected governor of a state of the United States.

Science and technology

Many Japanese Americans have also gained prominence in science and technology. In 1979, biochemist Harvey Itano became the first Japanese American elected to the United States National Academy of Sciences. Charles J. Pedersen won the 1987 Nobel Prize in chemistry for his methods of synthesizing crown ethers. Yoichiro Nambu won the 2008 Nobel Prize in physics for his work on quantum chromodynamics and spontaneous symmetry breaking. Michio Kaku is a theoretical physicist specializing in string field theory, and a well-known science popularizer. Ellison Onizuka became the first Asian American astronaut and was the mission specialist aboard Challenger at the time of its explosion.

Art and literature

In the arts, Minoru Yamasaki was the architect of the World Trade Center. Artist Sueo Serisawa helped establish the California Impressionist style of painting. Other influential Japanese American artists include Chiura Obata, Isamu Noguchi, George Tsutakawa, and George Nakashima.

Japanese American recipients of the American Book Award include Milton Murayama, Ronald Phillip Tanaka, Miné Okubo, Keiho Soga, Taisanboku Mori, Sojin Takei, Muin Ozaki, Toshio Mori, William Minoru Hohri , Karen Tei Yamashita, Sheila Hamanaka, Lawson Fusao Inada, Ronald Takaki, Kimiko Hahn, Lois-Ann Yamanaka, Ruth Ozeki, Hiroshi Kashiwagi, and Yuko Taniguchi. Hisaye Yamamoto received an American Book Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1986.

Poet laureate of San Francisco Janice Mirikitani has published three volumes of poems. Lawson Fusao Inada was named poet laureate of the state of Oregon.

Music

Classical violinist Midori Gotō is a recipient of the prestigious Avery Fisher Prize, while world-renowned violinist Anne Akiko Meyers received an Avery Fisher career grant in 1993. Other notable Japanese American musicians include singer, actress and Broadway star Pat Suzuki; rapper Mike Shinoda of Linkin Park and Fort Minor, rapper Kikuo Nishi aka "KeyKool" of The Visionaries, original bassist Hiro Yamamoto of Soundgarden, guitarist James Iha of The Smashing Pumpkins fame; singer & songwriter, composer and Japanese expatriate Mari Iijima; Shodo Artist, J-Poet, Gravure Idols and BURN Flame Miki Ariyama; ukulele virtuoso Jake Shimabukuro, famous J-pop superstar Hikaru Utada and critically acclaimed singer-songwriter Rachael Yamagata, Matt Heafy lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist for the American Metal band Trivium.

Sports

Japanese Americans first made an impact in Olympic sports in the late 1940s and in the 1950s. Harold Sakata won a weightlifting silver medal in the 1948 Olympics, while Japanese Americans Tommy Kono (weightlifting), Yoshinobu Oyakawa (100-meter backstroke), and Ford Konno (1500-meter freestyle) each won gold and set Olympic records in the 1952 Olympics. Konno won another gold and silver swimming medal at the same Olympics and added a silver medal in 1956, while Kono set another Olympic weightlifting record in 1956. Also at the 1952 Olympics, Evelyn Kawamoto won two bronze medals in swimming.

More recently, Eric Sato won gold (1988) and bronze (1992) medals in volleyball, while his sister Liane Sato won bronze in the same sport in 1992. In 1985, sansei Teiko Nishi from North Torrance became the first Asian American to start on a NCAA Division 1 Women's Basketball team at UCLA.[citation needed] Hapa Bryan Clay won the decathlon gold medal in the 2008 Olympics, the silver medal in the 2004 Olympics, and was the sport's 2005 world champion. Hapa Apolo Anton Ohno won eight Olympic medals in short-track speed skating (two gold) in 2002, 2006, and 2010, as well as a world cup championship.

In figure skating, Kristi Yamaguchi, a fourth-generation Japanese American, won three national championship titles (one in singles, two in pairs), two world titles, and the 1992 Olympic Gold medal. Rena Inoue, a Japanese immigrant to America who later became a U.S. citizen, competed at the 2006 Olympics in pair skating for the United States. Kyoko Ina, who was born in Japan, but raised in the United States, competed for the United States in singles and pairs, and was a multiple national champion and an Olympian with two different partners. Mirai Nagasu won the 2008 U.S. Figure Skating Championships at the age of 14 and became the second youngest woman to ever win that title.

In distance running, Miki (Michiko) Gorman won the Boston and New York City marathons twice in the 1970s. A former American record holder at the distance, she is the only woman to win both races twice, and is the only woman to win both marathons in the same year.

In professional sports, Wataru Misaka broke the NBA color barrier in the 1947–48 season, when he played for the New York Knicks. Misaka also played a key role in Utah's NCAA and NIT basketball championships in 1944 and 1947. Wally Kaname Yonamine was a professional running back for the San Francisco 49ers in 1947. Lindsey Yamasaki was the first Asian American to play in the WNBA and finished off her NCAA career with the third-most career 3-pointers at Stanford University.

Hikaru Nakamura became the youngest American ever to earn the titles of National Master (age 10) and International Grandmaster (age 15) in chess. In 2004, at the age of 16, he won the U.S. Chess Championship.

Entertainment and media

Miyoshi Umeki won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress in 1957. Actors Sessue Hayakawa, Mako Iwamatsu, and Pat Morita were nominated for Academy Awards in 1957, 1966, and 1984 respectively. Chris Tashima won the Academy Award for Best Live Action Short Film in 1997.

Jack Soo (Valentine's Day and Barney Miller), George Takei (Star Trek fame) and Pat Morita (Happy Days) helped pioneer acting roles for Asian Americans while playing secondary roles on the small screen during the 1960s and 1970s. In 1976, Morita also starred in Mr. T and Tina, which was the first American sitcom centered on a person of Asian descent. Lisa Yamanaka was famous for voicing the character Wanda Li in The Magic School Bus which is currently on Qubo. Keiko Yoshida was cast in the past TV show ZOOM in PBS Kids. Gregg Araki (film director of independent films) is also Japanese American.

Today, Shin Koyamada launched a leading role in the Warner Bros. epic movie The Last Samurai and Disney Channel movie franchise Wendy Wu: Homecoming Warrior and TV series Disney Channel Games. Masi Oka plays a prominent role in the NBC series Heroes, Grant Imahara appears on the Discovery Channel series MythBusters and Derek Mio appears in the NBC series Day One.

Japanese Americans now anchor TV newscasts in markets all over the country. Notable anchors include Tritia Toyota, Adele Arakawa, David Ono, Kent Ninomiya, and Lori Matsukawa.

Works about Japanese Americans

See also categories: Japanese-American internment films and Japanese-American internment books.- Japanese Americans. In 2010 TBS produced a 5 part, 10hr fictional Japanese language miniseries featuring many of the major events and themes of the Issei and Nisei experience, including emigration, racism, picture brides, farming, pressure due to the China and Pacific wars, internment, a key character who serves in the 442nd and the ongoing redefinition in identity of what it means to be Japanese and American.[12]

See also

- Asian American

- Asian Canadian

- Hyphenated American

- Japanese American Citizens League

- Japanese American National Library

- Japanese American National Museum

- Japanese Canadian

- Japanese Brazilian

- Japanese British

- Japanese Mexican

- Japanese people

- List of Japanese Americans

- Model minority

- Nisei Baseball Research Project

- Pacific Movement of the Eastern World

- Chicago Shimpo

Notes

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Japanese alone or in combination in 2007". http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/IPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-geo_id=NBSP&-qr_name=ACS_2007_1YR_G00_S0201&-qr_name=ACS_2007_1YR_G00_S0201PR&-qr_name=ACS_2007_1YR_G00_S0201T&-qr_name=ACS_2007_1YR_G00_S0201TPR&-ds_name=ACS_2007_1YR_G00_&-reg=ACS_2007_1YR_G00_S0201:041;ACS_2007_1YR_G00_S0201PR:041;ACS_2007_1YR_G00_S0201T:041;ACS_2007_1YR_G00_S0201TPR:041&-_lang=en&-redoLog=false&-format=. Retrieved 2008-10-26

- ^ Every Culture – Japanese

- ^ Doi, Mary L. "A Transformation of Ritual: The Nisei 60th Birthday." Journal Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. Vol. 6, No. 2 (April, 1991).

- ^ Schodt, Frederik L. (2003). Native American in the Land of the Shogun: Ranald MacDonald and the Opening of Japan. Stone Bridge Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-1880656778. http://books.google.com/books?id=3NTiU0fOh20C.

- ^ Tate, Cassandra (2009-07-23). "Japanese Castaways of 1834: The Three Kichis". HistoryLink.org. http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=9065.

- ^ "California Marks the First Fred Korematsu Day". TIME. Jan. 29, 2011. http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,2045111,00.html.

- ^ "Fred Korematsu Day a first for an Asian American". San Francisco Chronicle. Saturday, January 29, 2011. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=%2Fc%2Fa%2F2011%2F01%2F29%2FMNL61HFQI4.DTL.

- ^ "A civil rights hero gets his day". Los Angeles Times. January 31, 2011. http://www.latimes.com/news/local/la-me-0131-korematsu-20110131,0,4669201,full.story.

- ^ Steffen, Jordan (October 6, 2010). "White House honors Japanese American WWII veterans". The Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com/news/nationworld/nation/la-na-veterans-medal-20101006,0,7017069.story

- ^ Lobe, Jim (September 16, 2004). "Asian-Americans lean toward Kerry". AsiaTimes. http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Front_Page/FI16Aa01.html

- ^ http://www.sfjapantown.org/About/

- ^ "Northern California Premiere of '99 Years of Love'". Rafu Shimpo. April 12, 2011. http://rafu.com/news/2011/04/northern-california-premiere-of-%E2%80%9999-years-of-love%E2%80%99/

Further reading

- "Present-Day Immigration with Special Reference to the Japanese," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (Jan 1921), pp. 1-232 online 24 articles by experts, mostly about California

- Inouye, Karen M., “Changing History: Competing Notions of Japanese American Experience, 1942–2006” (PhD dissertation Brown University, 2008). Dissertation Abstracts International No. DA3318331.

- Lai, Eric, and Dennis Arguelles, eds. "The New Face of Asian Pacific America: Numbers, Diversity, and Change in the 21st century." San Francisco, CA: Asian Week, 2003.

- Kikumura-Yano, Akemi, ed. "Encyclopedia of Japanese Descendants in the Americas." Walnut Creek, CA: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002.

- Moulin, Pierre. (1993). U.S. Samurais in Bruyeres – People of France and Japanese Americans: Incredible story Hawaii CPL Editions. ISBN 2-9599984-0-5

- Moulin, Pierre. (2007). Dachau, Holocaust and US Samurais – Nisei Soldiers first in Dachau Authorhouse Editions. ISBN 978-1-4259-3801-7

External links

- Japanese American National Museum

- Embassy of Japan in Washington, DC

- Japanese American Citizens League

- Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii

- Japanese Cultural & Community Center of Northern California

- Japanese American Community and Cultural Center of Southern California

- Japanese American Historical Society

- Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project

- Japanese American Museum of San Jose, California

- Japanese American Network

- Japanese-American's own companies in USA

- Japanese American Relocation Digital Archives

- Online Archive of the Japanese American Relocation during World War II

- Photo Exhibit of Japanese American community in Florida

- The Asians in America Project – Japanese American Organizations Directory

- Nikkei Federation

- Discover Nikkei

- Summary of a panel discussion on changing Japanese American identities

- Interment and American samurai

- “The War Relocation Centers of World War II: When Fear Was Stronger than Justice”, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- U.S. Government interned Japanese from Latin America

- Short radio episode Baseball from "Lil' Yokohama" by Toshio Mori, 1941. California Legacy Project.

Asian Americans East Asian

South Asian2 Southeast Asian Burmese · Cambodian · Filipino · Hmong · Indonesian · Laotian · Laotian Chinese · Mien · Singaporean · Thai · VietnameseOther History 1 The US Census Bureau reclassifies anyone identifying as "Tibetan American" as "Chinese American". [1].

2 The US Census Bureau considers Afghanistan a South Asian country, but does not classify Afghan Americans as Asian. [2]Japanese diaspora and Japanese expatriates Africa Egypt · South Africa

Americas North AmericaSouth AmericaAsia China (Hong Kong) · India · Indonesia · North Korea · Malaysia · Nepal · Pakistan · Philippines · Singapore · Sri Lanka · Thailand · United Arab Emirates · VietnamEurope Oceania ElsewhereSee Also GenerationsRelated articlesCategories:- American people of Japanese descent

- Japanese diaspora

- Ethnic groups in the United States

- American people of Asian descent

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.