- I, Claudius

-

This article is about the novel. For other uses, see I, Claudius (disambiguation).

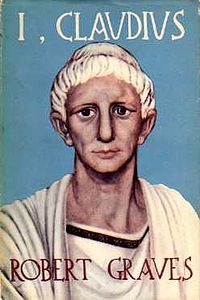

I, Claudius

First edition coverAuthor(s) Robert Graves Country United Kingdom Language English Genre(s) Historical novel Publisher Arthur Barker Publication date 1934 Media type Print (Hardback & Paperback) Pages 468 pp (paperback ed.) ISBN ISBN 0-679-72477-X OCLC Number 19811474 Dewey Decimal 823/.912 20 LC Classification PR6013.R35 I2 1989 Followed by Claudius the God I, Claudius (1934) is a novel by English writer Robert Graves, written in the form of an autobiography of the Roman Emperor Claudius. As such, it includes history of the Julio-Claudian Dynasty and Roman Empire, from Julius Caesar's assassination in 44 BC to Caligula's assassination in AD 41. The 'autobiography' of Claudius continues (from Claudius's accession after Caligula's death, to his own death in 54) in Claudius the God (1935). The sequel also includes a section written as a biography of Herod Agrippa, contemporary of Claudius and future King of the Jews. The two books were adapted by the BBC into an award-winning television serial, I, Claudius.

In 1998, the Modern Library ranked I, Claudius fourteenth on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century.

In 2005, the novel was chosen by TIME magazine as one of the one hundred best English-language novels from 1923 to present.[1]

Contents

The novels

Content

Claudius was the fourth Emperor of Rome (r. 41-54 A.D.). Historically, Claudius' family kept him out of public life until his sudden coronation at the age of forty nine. This was due to his disabilities, which included a stammer, a limp, and various nervous tics which made him appear mentally deficient to his relatives. This is how he was defined by scholars for most of history, and Graves uses these peculiarities to develop a sympathetic character whose survival in a murderous dynasty depends upon his family's incorrect assumption that he is a harmless idiot.

Graves's interpretation of the story owes much to the histories of Gaius Cornelius Tacitus, Plutarch, and (especially) Suetonius (Lives of the Twelve Caesars). Graves translated Suetonius before writing the novels. Graves claimed that after he read Suetonius, Claudius came to him in a dream one night and demanded that his real story be told. The life of Claudius provided Graves with a way to write about the first four Emperors of Rome (Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, and Claudius) from an intimate point of view. In addition, the real Claudius was a trained historian and is known to have written an autobiography (now lost) in eight books that covered the same time period. I, Claudius is a first-person narrative of Roman history from the reigns of Augustus to Caligula; Claudius the God is written as a later addition documenting Claudius' own reign.

Graves provides a theme for the story by having the fictionalized Claudius describe a visit to Cumae, where he receives a prophecy in verse from the Sibyl, and an additional prophecy contained in a book of "Sibylline Curiosities". The latter concerns the fates of the "hairy ones" (i.e. The Caesars - from the Latin word "caesar", meaning "a fine head of hair") who are to rule Rome. The penultimate verse concerns his own reign, and Claudius assumes that he can tell the identity of the last emperor described. From the outset, then, Graves establishes a fatalistic tone that plays out at the end of Claudius the God, as Nero prepares to succeed Claudius.

At Cumae, the Sibyl tells Claudius that he will "speak clear." Claudius believes this means that his secret memoirs will be one day found, and that he, having therein written the truth, will speak clearly, while his contemporaries, who had to distort their histories in order to appease the ruling family, will seem like stammerers. Since he wishes to record his life for posterity, Claudius chooses to write in Greek, since he believes that it will remain "the chief literary language of the world." This allows Graves to explore the etymology of Latin words (like the origins of the names "Livia" and "Caesar") that would otherwise be obvious to native Latin speakers, who Claudius (correctly) believes will not exist in the future.

Major themes

Themes treated by the novel include the conflict between liberty (as demonstrated by the Roman Republic, and the dedication to its ideals shown by Augustus and young Claudius), and the stability of Empire and centralized rule (as represented by Livia Drusilla, Herod Agrippa, and the older Claudius). The Republic provided freedom but was inherently unstable and threw the doors open to perennial civil wars, the last of which was ended by Augustus after twenty years of fighting. While Augustus harbours Republican sentiments, his wife Livia manages to convince him that to lay down his Imperial powers would mean the destruction of the peaceful society they have made. Likewise, when the similarly minded Claudius becomes emperor, he is convinced by Valeria Messalina and Herod to preserve his powers, for much the same reason. However, Graves acknowledges that there must be a delicate balance between Republican liberty and Imperial stability; whereas too much of the former led to civil war, too much of the latter led to the corruption of Tiberius, Caligula, Valeria Messalina, Sejanus, Herod Agrippa, Nero, Agrippina the Younger, and countless others – as well as, to a lesser extent, Livia and Claudius himself.

Near the end of Claudius the God, Graves introduces another concept: when a formerly free nation has lived under a dictatorship for too long, it is incapable of returning to free rule. This is highlighted by Claudius's failed attempts to revive the Republic; by the attempts of various characters to 'restore' the Republic but with themselves as the true rulers; and by Claudius noting that 'by dulling the blade of tyranny, I reconciled Rome to the monarchy' – i.e., in his attempts to rule autocratically but along more Republican lines, he has only made the Roman people more complacent about living under a dictatorship.

The female characters are quite powerful, as in Graves's other works. Livia Drusilla, Valeria Messalina, and Agrippina the Younger clearly function as the powers behind their husbands, lovers, fathers, brothers, sons and/or daughters. The clearest example is provided by Augustus and Livia: whereas he would have inadvertently caused civil war, she manages, through constant and adroit manipulation, to preserve the peace, prevent a return to the Republic, and keep her own relatives in power. Roman women played little overt role in public life, so the often unpleasant but always significant events supposedly instigated behind the scenes by women allow Graves to develop vital, powerful female characters.

Literary significance and criticism

The I, Claudius novels, as they are called collectively, became massively popular when first published in 1934 and gained literary recognition with the award of the 1934 James Tait Black Prize for fiction. They are probably Graves's best known work aside from his myth essay The White Goddess, his English translation of The Golden Ass and his own autobiography Goodbye to All That. Despite their critical and monetary success, Graves later professed a dislike for the books and their popularity. He claimed that they were written only from financial need on a strict deadline. Nonetheless, they are today regarded as pioneering masterpieces of historical fiction.

Adaptations

Film and television

In 1937, abortive attempts were made to adapt the first book into a film I, Claudius by the film director Josef von Sternberg. The producer was Alexander Korda then married to Merle Oberon who was cast as Claudius' wife Messalina. Emlyn Williams was cast as Caligula, Charles Laughton was cast as Claudius, and Flora Robson was cast as Livia. Filming was abandoned after Oberon was injured in a serious motor car accident.

In 1976, BBC Television adapted the book and its sequel into the popular TV serial, also entitled I, Claudius. The production won four BAFTAs in 1977 and three Emmys in 1978.

In 2008, it was reported that Relativity Media had obtained the rights to produce a new film adaptation of I, Claudius. Jim Sheridan was named as director.[2]

Radio

Main article: I, Claudius (radio adaptation)In November and December 2010, as part of the Classic Serial strand, BBC Radio 4 broadcast a series of six hour-long episodes of a dramatization of both novels, adapted by Robin Brooks and directed by Jonquil Panting.

Theatre

The novel has also been adapted for theatre. The 1972 production I, Claudius was written by John Mortimer and starred David Warner.[3]

Audio

Two different audio readings of the novel, both performed by Derek Jacobi, have been produced (both in abridged versions), one by Dove Audio (1986) and one by CSA Word (2007).

Frederick Davidson performed an unabridged reading for Blackstone Audiobooks in 2008.

In 1988, Jonathan Oliver performed an unabridged reading for ISIS Audio Books.

Later references

A. E. van Vogt wrote a novel, Empire of the Atom, which is a wholesale translation of Graves's novel into science fiction.

In the last page of The Areas of My Expertise, John Hodgman includes a table comparing his "future works" with I, Claudius.

The soliloquacious title has influenced the names of other works of fiction and autobiographies:

- I, Borg, Star Trek: The Next Generation episode

- I, Claud..., autobiography of Claud Cockburn

- I, Claudia, Canadian independent film

- I, Claudia, the first of a series of novels by Marilyn Todd, featuring her heroine, Claudia Seferius.

- I & Claudius: Travels with My Cat, accounts of travel by Clare de Vries and her Burmese cat Claudius

- I Cthulhu, a short story by Neil Gaiman

- I, Davros, four audiodrama plays about Davros, the creater of the Daleks from Doctor Who

- I, Gatto, autobiography of Australian boxer and gangland personality Mick Gatto

- I, Jedi, Star Wars Expanded Universe novel by Michael Stackpole

- I, Libertine, 1956 novel by Theodore Sturgeon

- I, Lovett BBC2 sitcom from 1989, starring Norman Lovett

- I, Lucifer (Glen Duncan), a novel by Glen Duncan

- I, Mengsk, novel in the world of StarCraft, about the three generations of the Mengsk family

- "I, Mudd", Star Trek episode featuring a conman Harry Mudd

- I, Partridge: We Need to Talk About Alan, the 2011 'autobiography' of fictional English TV and radio presenter Alan Partridge

- I, Phoolan Devi, autobigraphy of Indian female bandit Phoolan Devi

- I, Robot, 1939 Adam Link story by Eando Binder (unrelated to the Isaac Asimov story collection)

- I, Robot, 1950 science fiction story collection by Isaac Asimov, subsequently turned into a film (title taken from the Eando Binder novel)

- I, Rowboat, contribution to The Onion, by a row boat

- I, Strahd, a horror-fantasy novel by P. N. Elrod set in Ravenloft

- I, Tintin, documentary film about the author of the fictional adventurer

- Io, Caligola, Italian title of the re-cut infamous motion picture Caligula when re-released in Italy in 1984. Translated the title is "I, Caligula"

- Me, Claudius, a play presented by Sesame Street's Cookie Monster on Monsterpiece Theatre (Cookie Monster frequently confuses personal pronouns)

See also

References

- ^ "All Time 100 Novels". Time. http://www.time.com/time/2005/100books/the_complete_list.html. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Kit, Borys (12 September 2008). "Director Jim Sheridan eyes I, Claudius". Reuters. http://uk.reuters.com/article/idUKN1235080020080912. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ "The View from London". TIME. 18 September 1972. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,906412-2,00.html. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

External links

- GradeSaver study guide on I, Claudius with summary and analysis

- I, Claudius Project (concentrates on the BBC production)

- Encyclopedia of Television

- British Film Institute Screen Online (TV series)

- I, Claudius at the Internet Movie Database

- Web oficial de 'La Casa de Robert Graves' en Deià, Mallorca. De la Fundación Robert Graves.

- BBC Radio 4 Classic Serial: I, Claudius - Episode One

Categories:- 1934 novels

- I, Claudius

- Novel series

- Novels by Robert Graves

- Julio-Claudian Dynasty

- British historical novels

- Augustus in popular culture

- Books about Nero

- Secret histories

- Novels set in Ancient Rome

- British novels adapted into films

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.