- Mada'in Saleh

-

For the sura of the Qur'an of the same name, see Al-Hijr.

Al-Hijr Archaeological Site (Madâin Sâlih) * UNESCO World Heritage Site

A row of tombs from the al-Khuraymat group, Mada'in Saleh.Country Saudi Arabia Type Cultural Criteria ii, iii Reference 1293 Region ** Arab States Inscription history Inscription 2008 (32nd Session) * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List

** Region as classified by UNESCOMada'in Saleh (Arabic: مدائن صالح, madāʼin Ṣāliḥ), also called Al-Hijr or Hegra (so in Greek and Latin, e.g. by Pliny [1]), is a pre-Islamic archaeological site located in the Al-Ula sector, within the Al Madinah Region of Saudi Arabia.[2] A majority of the vestiges date from the Nabatean kingdom (1st century CE).[3] The site constitutes the kingdom's southernmost and largest settlement after Petra, its capital.[4][5] Traces of Lihyanite and Roman occupation before and after the Nabatean rule, respectively, can also be found in situ,[5] while accounts from the Qur’an tell of an earlier settlement of the area by the tribe of Thamud in the 3rd millennium BC.[6]

According to the Islamic text, the Thamudis, who would carve out homes in the mountains, were punished by Allah for their persistent practice of idol worship and for conspiring to kill the prophet whom He sent, the non-believers being struck by an earthquake and lightning blasts.[7] Thus, the site has earned a reputation down to contemporary times as a cursed place[2]— an image which the national government is attempting to overcome as it seeks to develop Mada'in Saleh, officially protected as an archaeological site since 1972, for its tourism potential.[2][7]

In 2008, for its well-preserved remains from late antiquity, especially the 131 rock-cut monumental tombs, with their elaborately ornamented façades, of the Nabatean kingdom,[8] UNESCO proclaimed Mada'in Saleh as a site of patrimony, becoming Saudi Arabia's first World Heritage Site.[9]

Contents

Name

The long history of the place and the multitude of cultures to have occupied the site have led to the several names that are still in use to refer to the area. The place is currently known as Mada'in Saleh, Arabic for "Cities of Saleh," which was coined by an Andalusian traveler in 1336 AD.[10] The name "Al-Hijr," Arabic for "rocky place," has also been used to allude to its topography.[5] Both names have been mentioned in the Qur’an when referring to the settlements found in the locality.[11] The ancient inhabitants of the area, the Thamudis and Nabateans, referred to the place as "Hegra".

Location

The archaeological site of Mada'in Saleh is situated 20 km (12.4 mi) north of the Al-`Ula town, 400 km (248.5 mi) north-west of Medina, and 500 km (310.7 mi) south-east of Petra, in modern-day Jordan.[5] The site is on a plain, at the foot of a basalt plateau, which forms the south-east portion of the Hijaz mountains.[5] The western and north-western portions of the site contain a water table that can be reached at a depth of 20 m (65.6 ft).[5] The setting is notable for its desert landscape, marked by sandstone outcrops of various sizes and heights.[7]

History

The Lihyans

Lihyan (Arabic:لحيان) is an ancient Arab kingdom. It was located in Mada'in Saleh, and is known for its Old North Arabian inscriptions dating to ca. the 6th to 4th centuries BCE. Dedanite is used for the older phase of the history of this kingdom since their capital name was Dedan (see Biblical Dedan), which is now called Al-`Ula oasis located in northwestern Arabia, some 110 km southwest of Teima.

The Lihyanites later became allies of the Nabataeans.[12] Little is known about the Lihyan kingdom. Arab genealogies consider the Banu Lihyan to be descended from Ishmael.

Pre-Nabatean vestiges

Archaeological traces of cave art on the sandstones and epigraphic inscriptions, considered by experts to be Lihyanite script, on top of the Athleb Mountain,[6] near Mada'in Saleh, have been dated to the 3rd–2nd century BCE,[5] indicating the early human settlement of the area, which has an accessible source of freshwater and fertile soil.[6][13] The settlement of the lihyans became a center of commerce, with goods from the east, north and south converging in the locality.[6]

Nabatean settlements

Myrrh was one of the luxury items that had to pass through the Nabatean territory to be traded elsewhere.

The extensive settlement of the site took place during the 1st century CE,[3] when it came under the rule of the Nabatean king Al-Harith IV (9 BCE –40 CE), who made Mada'in Saleh the kingdom's second capital, after Petra in the north.[6] The place enjoyed a huge urbanization movement, turning it into a city.[6] Characteristic of Nabatean rock-cut architecture, the geology of Mada'in Saleh provided the perfect medium for the carving of monumental and settlements, with Nabatean scripts inscribed on their façades.[5] The Nabateans also developed oasis agriculture[5]—digging wells and rainwater tanks in the rock and carving places of worship in the sandstone outcrops.[13] Similar structures were featured in other Nabatean settlements, ranging from southern Syria to the north, going south to the Negev, and down to the immediate area of Hedjaz.[5] The most prominent and the largest of these is Petra.[5]

At the crossroad of commerce, the Nabatean kingdom flourished, holding a monopoly for the trade of incense, myrrh and spices.[7][14] Situated on the overland caravan route and connected to the Red Sea port of Egra Kome,[5] Mada'in Saleh, then referred to as Hegra among the Nabateans, reached its peak as the major staging post on the main north–south trade route.[13]

Post-Nabatean and Roman

In 106 CE, the Nabatean kingdom was annexed by the contemporary Roman Empire.[14][15] The Hedjaz region, which encompasses Hegra, became part of the Roman province of Arabia.[5]

The Hedjaz region was integrated into the Roman province of Arabia in 106 CE. A monumental Roman epigraph of 175-177 CE was recently discovered at Al-Hijr (then called "Hegra" and now Mada'in Saleh).[16]The trading itinerary shifted from the overland north–south axis on the Arabian Peninsula to the maritime route through the Red Sea.[13] Thus, Hegra as a center of trade began to decline, leading to its abandonment.[15] Supported by the lack of later developments based on archaeological studies, experts have hypothesized that the site had lost all of its urban functions beginning in the late Antiquity (mainly due to the process of desertification)[5].

Recently has been discovered evidence that Roman legions of Trajan occupied Madain Salih in the Hijaz mountain area of northeastern Arabia, increasing the extension of the "Arabia Petraea" province of the Romans in Arabia.[17]

The history of Hegra from the decline of the Roman Empire until the emergence of Islam remains unknown.[15] It was only sporadically mentioned by travelers and pilgrims making their way to Mecca in the succeeding centuries.[13] Hegra served as a station along the religious route, providing supplies and water for pilgrims.[15] Among the accounts is a description made by 14th-century traveler Ibn Battuta, noting the red stone-cut tombs of Hegra, by then known as Al-Hijr.[5] However, he made no mention of human activities there.

Under the Ottoman rule which began in the 16th century,[18] a fort was built on Al-Hijr, from 1744 to 1757.[5][13] It was part of a series of fortifications built to protect the pilgrimage route to Mecca.

Accounts from the Qur’an

According to the Qur’an, by the 3rd millennium BCE, the site of Mada'in Saleh had already been settled by the tribe of Thamud.[6] It is said that the tribe fell to idol worshipping; tyranny and oppression became prevalent.[19] The Prophet Saleh, to whom the site's name of Mada'in Saleh is often attributed,[13] called the Thamudis to repent.[19] The Thamudis disregarded the warning and instead commanded Prophet Saleh to summon a pregnant she-camel from the back of a mountain. And so, a pregnant she-camel was sent to the people from the back of the mountain by Allah, as proof of Saleh's divine mission.[11][19] However, only a minority heeded his words. The non-believers killed the sacred camel instead of caring for it as they were told, and its calf ran back to the mountain where it had come from, screaming. The Thamudis were given three days before their punishment was to take place, since they disbelieved they did not heed the warning.The prophet and the believers left the city, but the Thamudis were punished by Allah —their souls leaving their lifeless bodies in the midst of an earthquake and lightning blasts.[7][19]

From the 20th century onward

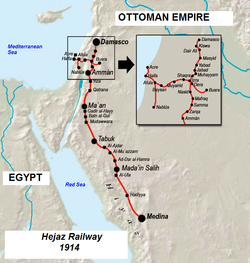

In the 19th century, there were accounts that the extant wells and oasis agriculture of Al-Hijr were being periodically used by settlers from the nearby village of Tayma. This continued until the 20th century, when a railway passing through the site was constructed (1901–08) on the orders of Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid II to link Damascus and Jerusalem in the north-west with Medina and Mecca,[13][15] hence facilitating the pilgrimage journey to the latter and to politically and economically consolidate the Ottoman administration of the centers of Islamic faith.[20] A station was built north of Al-Hijr for the maintenance of locomotives, and offices and dormitories for railroad staff.[13] The railway provided greater accessibility to the site. However, this was destroyed in a local revolt during World War I.[21] Despite this, several archaeological investigations continued to be conducted in the site beginning in the World War I period to the establishment of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in the 1930s up to the 1960s.[5][22] The railway station has also been restored and now includes 16 buildings and several pieces of rolling stock.[23]

By the end of the 1960s, the Saudi Arabian government devised a program to introduce a sedentary lifestyle to the nomadic Bedouin tribes inhabiting the area.[5] It was proposed that they settle down on Al-Hijr, re-using the already existent wells and agricultural features of the site.[5] The official identification of Al-Hijr as an archaeological site in 1972 however, led to the resettlement of the Bedouins towards the north, beyond the site boundary.[5] This also included the development of new agricultural land and freshly dug wells, thereby preserving the state of Al-Hijr.

Current development

Although the Al-Hijr site was proclaimed as an archaeological treasure in the early 1970s, few investigations had been conducted since.[2] The prohibition on the veneration of objects/artifacts has only resulted in minimal low-key archaeological activities. These conservative measures have started to ease up beginning in 2000, when Saudi Arabia invited expeditions to carry out archaeological explorations, as part of the government's push to promote cultural heritage protection and tourism.[2][7] The archaeological site was proclaimed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008.[9]

Architecture

The Nabatean site of Hegra was built around a residential zone and its oasis during the 1st century CE.[5] The sandstone outcrops were carved out to build the necropolis. A total of four necropolis areas have survived, which featured 131 monumental rock-cut tombs spread out over 13.4 km (8.3 mi),[8][24] many with inscribed Nabatean epigraphs on their façades:

Necropolis Location Period of construction Notable features Jabal al-Mahjar North no information Tombs were cut on the eastern and western sides of four parallel rock outcrops. Façade decorations are small in size.[5] Qasr al walad no information 0–58 CE Includes 31 tombs decorated with fine inscriptions as well as artistic elements like birds, human faces and imaginary beings. Contains the most monumental of rock-cut tombs, including the largest façade measuring 16 m (52.5 ft) high.[5] Area C South-east 16–61 CE Consists of a single isolated outcrop containing 19 cut tombs.[25] No ornamentations were carved on the façades.[5] Jabal al-Khuraymat South-west 7–73 CE The largest of the four, consisting of numerous outcrops separated by sandy zones, although only eight of the outcrops have cut tombs, totaling 48 in quantity.[5] The poor quality of sandstone and exposure to prevailing winds resulted to the poor state of conservation of most façades.[25] Non-monumental burial sites, totaling 2,000, are also part of the place.[5]

A closer observation of the façades indicates the social status of the buried person[13]—the size and ornamentation of the structure reflect the wealth of the person. Some façades had plates on top of the entrances providing information about the grave owners, the religious system, and the masons who carved them.[7] Many graves indicate military ranks, leading archaeologists to speculate that the site might have once been a Nabatean military base, meant to protect the settlement's trading activities.[6]

The archaeological vestiges of Mada'in Saleh are often compared with those of Petra, the Nabatean capital situated 500 km (310.7 mi) north-west of Mada'in Saleh.[5]

The Nabatean kingdom was not just situated at the crossroad of trade but also of culture. This is reflected in the varying motifs of the façade decorations, borrowing stylistic elements from Assyria, Phoenicia, Egypt and Hellenistic Alexandria, combined with the native artistic style.[5] Roman decorations and Latin scripts also figured on the troglodytic tombs when the territory was annexed by the Roman Empire.[2] In contrast to the elaborate exteriors, the interiors of the rock-cut structures are severe and plain.[7]

A religious area, known as Jabal Ithlib, is located to the north-east of the site.[5] It is believed to have been originally dedicated to the Nabatean deity Dushara. A narrow corridor, 40 metres (131 ft) long between the high rocks and reminiscent of the Siq in Petra, leads to the hall of the Diwan, a Moslem council chamber or law court.[5] Small religious sanctuaries bearing inscriptions were also cut into the rock in the vicinity.

The residential area is located on the middle of the plain, far from the outcrops.[5] The primary material of construction for the houses and the enclosing wall was sun-dried mudbrick.[5] Few vestiges of the residential area remain.

Water is supplied by 130 wells, situated in the western and north-western part of the site, where the water table was at a depth of only 20 m (65.6 ft).[5] The wells, with diameters ranging 4–7 m (13.1–23.0 ft), were cut into the rock, although some, dug in loose ground, had to be reinforced with sandstone.[5]

Importance

The Al-Hijr archaeological site lies in an arid environment. The dry climate, the lack of resettlement after the site was abandoned, and the prevailing local beliefs about the locality have all led to the extraordinary state of preservation of Al-Hijr,[5] providing an extensive picture of the Nabatean lifestyle. Thought to mark the southern extent of the Nabatean kingdom,[4] Al-Hijr's oasis agriculture and extant wells exhibit the necessary adaptations made by the Nabateans in the given environment—its markedly distinct settlement is the second largest among the Nabatean kingdom, complementing that of the more famous Petra archaeological site in Jordan.[5] The location of the site at the crossroads of trade, as well as the various languages, scripts and artistic styles reflected in the façades of its monumental tombs further set it apart from other archaeological sites. It has duly earned the nickname "The Capital of Monuments" among Saudi Arabia's 4,000 archaeological sites.[2][13]

See also

- Saleh

- Petra

- Nabataeans

- Roman Arabia

- Thamud

- List Of Colossal Sculpture In Situ

- Ancient Towns in Saudi Arabia

Footnotes

- ^ Melikian, Souren (2010-07-23). "'Routes of Arabia' Exhibition at Louvre Is Startling". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/24/arts/24iht-melik24.html?_r=3&pagewanted=2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Abu-Nasr, Donna (2009-08-30). "Digging up the Saudi past: Some would rather not". Associated Press. http://www.google.com/hostednews/ap/article/ALeqM5j5-VuZTJYWXZ0lwZ9LQ-5PrHXgPAD9ADBRJO0. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ a b The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Macropædia Volume 13. USA: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.. 1995. pp. 818. ISBN 0-85229-605-3.

- ^ a b "Expansion of the Nabataeans". http://madainsaleh.net/expansion_of_nabataeans.aspx. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj "ICOMOS Evaluation of Al-Hijr Archaeological Site (Madâin Sâlih) World Heritage Nomination". World Heritage Center. http://whc.unesco.org/archive/advisory_body_evaluation/1293.pdf. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Creation of Al-Hijr". http://madainsaleh.net/creation_of_al_hijr.aspx. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ a b "Information at nabataea.net". http://nabataea.net/medain.html. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ a b "Official announcement as World Heritage Site". UNESCO. http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=42986&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ "Madain Saleh tour service". http://www.alibaba.com/product-free/245486167/Madain_Saleh_tour_service.html. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- ^ a b "Madain Saleh – Cities inhabited by the People of Thamud". http://www.iqrasense.com/islamic-history/madain-saleh-cities-inhabited-by-the-people-of-thamud.html. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ Gibson (2011), p. 135.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Madain Saleh". http://madainsaleh.net/index.aspx. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ a b The New Encyclopædia Britannica Micropædia Volume 8. USA: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.. 1995. pp. 473. ISBN 0-85229-605-3.

- ^ a b c d e "Fall of Al-Hijr". http://madainsaleh.net/fall_of_al_hijir.aspx. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ Roman presence in Hegra (actual Madain Saleh)

- ^ Romans at Madain Salih, in northeastern Arabian peninsula

- ^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica Macropædia Volume 13. 1995, p. 820.

- ^ a b c d "Explanation of the Verses". http://madainsaleh.net/explanation_of_the_verses.aspx. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ Baker, Randall (1979). King Hussein And The Kingdom of Hejaz. pp. 18. ISBN 0900891483.

- ^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica Micropædia Volume 5. USA: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.. 1995. pp. 809. ISBN 0-85229-605-3.

- ^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Macropædia Volume 13. 1995, p. 840.

- ^ "Move Under Way to Restore Madain Saleh Railway Station". Arab News. 2006-06-22. http://www.arabnews.com/?page=1§ion=0&article=84182&d=22&m=6&y=2006. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ "Al-Hijr". http://madainsaleh.net/al_hijr.aspx. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ a b "Tourist sites in Madain Saleh". http://madainsaleh.net/tourist_sites_in_madain_saleh.aspx. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

References

- Gibson, Dan (2011). Qur’anic Geography: A Survey and Evaluation of the Geographical References in the Qur’an with Suggested Solutions for Various Problems and Issues. Independent Scholars Press, Canada. ISBN 978-0-9733642-8-6.

Further reading

- Abdul Rahman Ansary, Ḥusayn Abu Al-Ḥassān, The civilization of two cities: Al-ʻUlā & Madāʼin Sāliḥ, 2001, ISBN 9960930106, ISBN 9789960930107

- Mohammed Babelli: Mada’in Saleh – Riyadh, Desert Publisher (arab, english, francia and deutsch publ), I./2003, II./2005, III./2006, IV./2009. – ISBN 978 603 00 2777 4

External links

- Personal website on Hegra (Madain Saleh) (picture, text, map, video and sound) at hegra.fr

- Photo gallery at nabataea.net

- World Heritage listing submission

- Photos from Mauritian photographer Zubeyr Kureemun

- Historical Wonder by Mohammad Nowfal

- Saudi Arabia's Hidden City from France24

- Madain Salah: Saudi Arabia's Cursed City

World Heritage Sites in Saudi Arabia Al-Hijr Archaeological Site · At-Turaif District in ad-Dir'iyah

Categories:

Categories:- Nabataea

- Archaeological sites in Saudi Arabia

- Pre-Islamic Arabia

- World Heritage Sites in Saudi Arabia

- Arabic architecture

- Former populated places in Southwest Asia

- Railway museums in Saudi Arabia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.