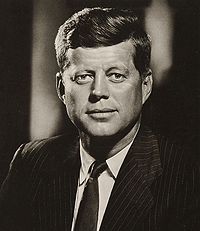

- Reaction to the assassination of John F. Kennedy

-

Around the world, there was a stunned reaction to the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the President of the United States, on November 22, 1963 in Dallas, Texas.[1]

The first hour after the shooting, before his death was announced, was a time of great confusion. Taking place during the Cold War, it was at first unclear whether the shooting might be part of a larger attack upon the U.S., and whether Vice-President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had been riding two cars behind in the motorcade, was safe.

The news shocked the nation. Men and women wept openly. People gathered in department stores to watch the television coverage, while others prayed. Traffic in some areas came to a halt as the news spread from car to car.[2] Schools across the U.S. dismissed their students early.[3] Anger against Texas and Texans was reported from some individuals. Various Cleveland Browns fans, for example, carried signs at the next Sunday's home game against the Dallas Cowboys decrying the city of Dallas as having "killed the President."[4][5]

The event left a lasting impression on many Americans. As with the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor before it and the September 11, 2001 attacks after it, asking "Where were you when you heard about Kennedy's assassination" would become a common topic of discussion.[6][7]

Contents

The reaction

In the United States, the assassination dissolved differences among all people as they were brought together in one common theme: shock and sorrow after the assassination.[8] It was seen in statements by the former presidents and members of Congress, etc.[8] The news was so shocking and hit with such impact;[8] according to the Nielsen Audimeter Service, within 40 minutes of the first reporting of the assassination, the television audience doubled, by early evening, 70% was at their television sets.[9]

CBS Washington correspondent Roger Mudd summed it all up: "It was a death that touched everyone instantly and directly; rare was the person who did not cry that long weekend. In our home, as my wife (E.J.) watched the television, her tears caused our five-year-old son, Daniel, to go quietly and switch off of what he thought was the cause of his mother's weeping."[10]

Around the world

After the assassination, many world leaders expressed shock and sorrow, some going on television and radio to address their countrymen.[11][12] In countries around the world, state premiers and governors and mayors also issued messages expressing shock over the assassination. Many of them wondered if the new president, Lyndon Johnson, would carry on Kennedy's policies or not. LBJ and the world would sympathize from the "concern etched on Mr. Johnson's face."[13]

In many countries, radio and television networks, after breaking the news, either went off the air except for funeral music or broke schedules to carry uninterrupted news of the assassination, and if Kennedy had made a visit to that country, recalled that visit in detail.[14][15] In several nations, monarchs ordered the royal family into days of mourning.[14]

At U.S. embassies and consulates around the world, switchboards lit up and were flooded with phone calls.[16] At many of them, shocked personnel often let telephones go unanswered. They also opened up condolence books for people to sign.[16] In Europe, the assassination tempered Cold War sentiment, as people on both sides expressed shock and sorrow.[17]

News of the assassination reached Asia during the early morning hours of November 23, 1963, because of the time difference, as people there were sleeping.[18][19] In Japan, the news became the first television broadcast from the United States to Japan via the Relay 1 satellite, instead of a prerecorded message from Kennedy to the Japanese people.[20]

Unofficial mourning

Hastily organized memorial services for Kennedy were held throughout the world, allowing many to express their grief. Governments ordered flags to half-staff and days of mourning. A day of national mourning and sorrow was declared in the U.S. for Monday, November 25, the day of the state funeral.[21][22] Many other countries did the same. Throughout the United States, many states declared the day of the funeral a legal holiday.[23]

Not all recreational and sporting events scheduled for the day of the assassination and during the weekend after were canceled. Those that went on shared the sentiment NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle expressed in deciding to play NFL games that weekend: "It has been traditional...to perform in times of great personal tragedy."[24] The Washington Redskins sent the game ball used in their win over the Philadelphia Eagles in Philadelphia to the White House, thanking Rozelle for allowing the games to be played that weekend.[25] Coach Bill McPeak said that the players on the Redskins asked him to send the ball to the White House because they said that they were "playing...for President Kennedy and in his memory."[26]

Mourning during the funeral

The initial CBS news bulletin of the shooting interrupting a live network program, As the World Turns, at 1:40 p.m. (EST) on November 22

The initial CBS news bulletin of the shooting interrupting a live network program, As the World Turns, at 1:40 p.m. (EST) on November 22

Mourning for Kennedy encompassed the world on the day of his funeral, November 25, 1963. The assassination shocked the world and people around the world attended memorial services.[27]

This was a day of national mourning in the United States and in most countries around the world.[23] Events were called off because of the mourning. Men and women everywhere were united in paying tribute to Kennedy. Town streets were deserted while services were held. Everyone who could followed the proceedings on television. Others heeded the call for the day of national mourning by going to their place of worship for a memorial service.[23] Around the world, the funeral procession was sent abroad via satellite.[28]

Schools, offices, stores, and factories were closed.[23] Those that were open scheduled a minute of silence.[23] Others permitted employees time off to attend memorial services. During memorial services, church bells tolled. In some cities, police officers attached black bands to their badges.[23]

In many states, governors declared the day of national mourning as a legal holiday in their state, allowing banks to close.[23] There was silence across the United States at 12:00 EST (17:00 UTC) for five minutes to mark the start of the funeral.[23] The somber mood across the nation during the weekend following Kennedy's death was evident on the broadcast airwaves. By 3 p.m. (EST) on November 22, nearly every television station canceled their commercial schedules to stay with around-the-clock news coverage provided by the three U.S. television networks in 1963: ABC, CBS, and NBC. From 3 p.m. that day until November 26, all network entertainment and commercial programming ceased on U.S. television.[29] The networks offered round the clock coverage, which was the first time any happening would get this kind of attention. Overnights included taped footage of earlier news mixed with a few breaking news items. On Sunday night, NBC broadcast continuous live coverage of mourners passing the flag-draped bier in the Capitol rotunda as an estimated 250,000 people filed by.[30]

Radio stations - even many Top 40 rock and roll outlets - also went commercial-free, with many non-network stations playing nothing but classical and/or easy listening instrumental selections interspersed with news bulletins. (It has been reported, though, that some stations in parts of the country where Kennedy was unpopular carried on with their normal programming as usual.) Most stations did return to normal programming on the day after the funeral. Phil Spector's Christmas album, A Christmas Gift for You from Phil Spector, was pulled from store shelves at Spector's request, having sold terribly since the public was not in the mood for cheery holiday music; it was put back for sale for the 1964 season but didn't chart until 1972. Its also believed that the release of Beatles music was delayed until early in 1964 as well.[citation needed]

The highly successful comedy album The First Family that parodied the Kennedys was quickly pulled from circulation which remained that way for many years.

Tributes following the assassination

Tributes to Kennedy abounded in the months following his murder, particularly in the world of recordings. Many individual radio stations released album compilations of their news coverage of Kennedy's assassination; ABC News released a two-LP set of its radio news coverage. Major record labels also released tribute albums; at one point there were at least six Kennedy tribute albums available for purchase in record stores, with the most popular being Dickie Goodman's John Fitzgerald Kennedy: The Presidential Years 1960-1963 (20th Century 3127), which climbed to number eight on the Billboard album chart and stood as the biggest-selling tribute album of all time until the double-CD tribute to Princess Diana of Wales thirty-four years later ([1]).

Two days after the assassination (and one day before the funeral), a special live television program entitled A Tribute to John F. Kennedy from the Arts was broadcast by ABC on network television. The program featured dramatic readings from such actors as Christopher Plummer, Sidney Blackmer, Florence Eldridge, Albert Finney, and Charlton Heston, as well as musical selections performed by such artists as Marian Anderson. Actor Fredric March (Ms. Eldridge's real-life husband) hosted the program. Plummer and Finney performed Hamlet's dying speech (I am dead, Horatio) with Finney taking the role of Horatio.[31] The program has never been repeated, nor has it ever been released on video in any form.

Perhaps the most successful Kennedy tribute song released in the months after his assassination (although later hit songs such as "Abraham, Martin and John" and "We Didn't Start the Fire" also referenced the tragedy) was the controversial "In the Summer of His Years", introduced by British singer Millicent Martin on a BBC-TV tribute to Kennedy. A cover version by Connie Francis climbed the Billboard charts to number 46 in early 1964 despite being banned by a number of major-market radio stations who felt that capitalizing on a national tragedy was in poor taste.[32] Other versions of the song were recorded by Toni Arden, Kate Smith, Bobby Rydell, and gospel legend Mahalia Jackson.[33]

British heavy metal band Saxon wrote Dallas 1PM as a tribute and the song featured the line, "The world was shocked that fateful day. A young man's life was blown away, at Dallas 1PM". Also in Britain (where the publishers of "In the Summer of His Years" refused to allow the song a single release by any British artist), Joe Meek, composer of The Tornadoes' hit "Telstar", released an instrumental titled "The Kennedy March" on Decca Records, with royalties marked to be sent to Jacqueline Kennedy for her to donate to charity.[33] The Briarwood Singers "Bubbled Under" the Billboard singles chart in December of 1963 with a recording of the traditional folk song He Was a Friend of Mine, which was later recorded (with new lyrics written specially by Jim McGuinn) in 1965 by the popular American band, The Byrds, on their second album, Turn! Turn! Turn!. In 1964, songwriter William Spivery penned, "Mr. John," which became popular in the midwestern United States.

References

- Inline citations

- ^ United Press International & American Heritage Magazine 1964, p. 43, 48–49

- ^ Associated Press 1963, p. 16

- ^ Associated Press 1963, p. 29

- ^ Associated Press (November 25, 1963). "Browns Set Back Cowboys, 27 to 17". New York Times: p. 35.

- ^ Loftus, Joseph A. (November 25, 1963). "Ruby is Regarded a 'Small-Timer'". New York Times: p. 12.

- ^ Brinkley, David (2003). Brinkley's Beat. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0375406441.

- ^ White 1965, p. 6

- ^ a b c White 1965, pp. 6–7

- ^ White 1965, p. 13

- ^ Mudd, Roger (2008). The place to be: Washington, CBS, and the glory days of television news. New York: PublicAffairs. p. 133. ISBN 9781586485764.

- ^ "World Leaders Voice Sympathy and Shock as Their Countries Mourn President". New York Times: p. 8. November 23, 1963.

- ^ United Press International & American Heritage Magazine 1964, pp. 46–47

- ^ Canadian Press (January 24, 1973). "LBJ Gets Commons Tributes". Winnipeg Free Press: p. 18.

- ^ a b "Many Nations Share America's Grief". New York Times: p. 6. November 24, 1963.

- ^ NBC News 1966, pp. 20–21, 24, 28–31

- ^ a b Assocaited Press 1963, p. 47

- ^ Associated Press 1963, p. 40

- ^ Associated Press 1963, p. 49

- ^ "Capitals of Asia Express Sorrow". New York Times: p. 12. November 23, 1963.

- ^ Rothenberg, Fred (November 6, 1983). "Television Comes of Age in 70 Hours of Assassination Coverage". Associated Press.

- ^ Kenworthy, E.W. (November 24, 1963). "Johnson Orders Day of Mourning". New York Times: p. 1.

- ^ United Press International American Heritage Magazine, pp. 52–53

- ^ a b c d e f g h Associated Press (November 26, 1963). "Cities Throughout U.S. Pause for Tribute to Kennedy". Washington Post: p. A4.

- ^ Brady, Dave (November 24, 1963). "It's Tradition To Carry on, Rozelle Says". The Washington Post: p. C2.

- ^ Walsh, Jack (November 25, 1963). "Game Ball Going to White House". The Washington Post: p. A16.

- ^ Associated Press (November 25, 1963). "Redskins Send Game Ball to White House". Chicago Tribune: p. C4.

- ^ "'A Sudden Extinction of a Shining Light'". Washington Post: p. A11. November 26, 1963.

- ^ Reuters (November 26, 1963). "Telstar Carries Rites". Chicago Tribune: p. 10.

- ^ "A permanent record of what we watched on television from Nov. 22 to 25, 1963". TV Guide 12 (4): 24-40. January 25, 1964.

- ^ NBC News 1966, pp. 122–123

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0284577/

- ^ Grevatt, Ren (28 December 1963). "Those Kennedy Singles Show Lively Sales Despite Slough-Off By Disc Jockeys". Billboard: 3.

- ^ a b "Music As Written". Billboard: 30–32. 21 December 1963.

- Bibliography

- Associated Press (1963). The Torch is Passed. New York.

- NBC News (1966). There Was a President. New York: Random House.

- White, Theodore Harold (1965). The making of the President, 1964. New York: Atheneum.

- United Press International; American Heritage Magazine (1964). Four Days. New York: American Heritage Pub. Co..

Assassination of John F. Kennedy Assassination Aftermath Autopsy · Reaction · Johnson inauguration · Funeral (Foreign Dignitaries) · Jack Ruby · Ruby v. Texas · Warren Commission · House Select Committee on Assassinations · Dictabelt evidence · Conspiracy theories · Single bullet theory · In popular culture · The Kennedy Half-Century

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.