- United States Constitution

-

United States Constitution

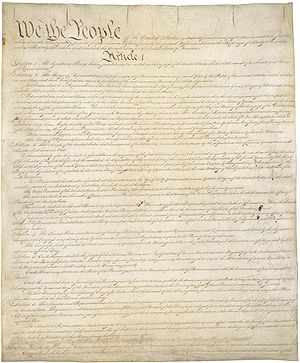

Page one of the original copy of the ConstitutionCreated September 17, 1787 Ratified June 21, 1788 Location National Archives,

Washington, D.C.Authors twelve state delegations in

Philadelphia ConventionSignatories 39 of the 55 Philadelphia Convention delegates Purpose National constitution to replace the Articles of Confederation The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It is the framework for the organization of the United States government and for the relationship of the federal government with the states, citizens, and all people within the United States.

The first three Articles of the Constitution establish the three branches of the national government: a legislature, the bicameral Congress; an executive branch led by the President; and a judicial branch headed by the Supreme Court. They also specify the powers and duties of each branch. All powers not enumerated are reserved to the respective states and the people, thereby establishing the federal system of government.

The Constitution was adopted on September 17, 1787, by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and ratified by conventions in each U.S. state in the name of "The People". It has been amended twenty-seven times; the first ten amendments are known as the Bill of Rights.[1][2]

The United States Constitution is the oldest written constitution (when defined as a single document) still in use by any nation in the world.[3] Parts of San Marino's Constitution are older, dating to the 1600s.[4][5] It holds a central place in United States law and political culture.[6] The handwritten original document penned by Jacob Shallus is on display at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C.

Contents

- 1 History

- 2 Original text

- 3 Amendments

- 4 Judicial review

- 5 "Civic religion"

- 6 Worldwide

- 7 Criticism

- 8 See also

- 9 Notes

- 10 References

- 11 Further reading

- 12 External links

1. History : Convention 2. Original text : three branches 3. Amendments : procedure -

House-proposal -

Senate-forwarded

4. Judicial review : establishment 5. “Civic religion” : The Shrine 6. Worldwide : national Constitutions History

Main article: History of the United States ConstitutionFirst government

Main article: Articles of ConfederationThe Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union were the first constitution of the United States of America.[7] The problem with the United States government under the Articles of Confederation was, in the words of George Washington, "no money".[8]

Congress could print money, but by 1786, the money was useless. Congress could borrow money, but could not pay it back.[8] Under the Articles, Congress requisitioned money from the states. But no state paid all of their requisition; Georgia paid nothing. A few states paid the U.S. an amount equal to interest on the national debt owed to their citizens, but no more.[8] Nothing was paid toward the interest on debt owed to foreign governments. By 1786 the United States was about to default on its contractual obligations when the principal came due.[8]

The United States could not defend itself as an independent nation in the world of 1787. Most of the U.S. troops in the 625-man U.S. Army were deployed facing British forts on American soil. The troops had not been paid; some were deserting and the remainder threatened mutiny.[9] Spain closed New Orleans to American commerce. The United States protested, to no effect. The Barbary Pirates began seizing American commercial ships. The Treasury had no funds to pay the pirates' extortion demands. The Congress had no more credit if another military crisis had required action.[8]

The states were proving inadequate to the requirements of sovereignty in a confederation. Although the 1783 Treaty of Paris had been made between Great Britain and the United States with each state named individually, individual states violated their peace treaty with Britain. New York and South Carolina repeatedly prosecuted Loyalists for wartime activity and redistributed their lands over the protests of both Great Britain and the Articles Congress.[8]

Mobbing "committees" disrupted cities in Ma, Ct, Pa, SC[10] like Shays' Rebellion. here, Paxtons at Philadelphia In Massachusetts during Shays' Rebellion, Congress had no money to support a constituent state, nor could Massachusetts pay for its own internal defense. General Benjamin Lincoln had to raise funds among Boston merchants to pay for a volunteer army.[11] During the upcoming Convention, James Madison angrily questioned whether the Articles of Confederation was a “solemn compact” or even government. Connecticut had not only sent none of its requisition, it had “positively refused" to pay Confederation assessments for two years.[12]A rumor had it that a "seditious party" among the New York legislature had opened communication with the Viceroy of Canada. To the south, the British were said to be funding the Creek Indian raids; Savannah was fortified, the State of Georgia under martial law.[13]

Congress was paralyzed. It could do nothing significant without nine states, and some legislative business required all thirteen. By April 1786 there had been only three days out of five months with nine states present. When nine states did show up, and there was only one member of a state on the floor, then that state’s vote did not count. If a delegation were evenly divided, the division was duly noted in the Journal, but there was no vote from that state towards the procedural nine-count requirement.[14] Individual state legislatures independently laid embargoes, negotiated unilaterally abroad, provided for armies and made war, all violating the letter and the spirit of the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union. The Articles Congress had “virtually ceased trying to govern.”[15]

The vision of a "respectable nation" among nations seemed to be fading in the eyes of such men as Virginia’s George Washington and James Madison, New York’s Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, Pennsylvania’s Benjamin Franklin and George Clymer and Massachusetts’ Henry Knox and Rufus King. The dream of a republic, a nation without hereditary rulers, with power derived from the people in frequent elections, was in doubt.[16]

Convention

Twelve state legislatures, Rhode Island being the only exception, sent delegates to convene at Philadelphia in May 1787.[17] While the resolution calling the Convention specified that its purpose was to propose amendments to the Articles, through discussion and debate it became clear by mid-June that the Convention would propose a Constitution with a fundamentally new design.[18]

Sessions

In September 1786, commissioners from five states met in the Annapolis Convention to discuss adjustments to the Articles of Confederation that would improve commerce. They invited state representatives to convene in Philadelphia to discuss improvements to the federal government. After debate, the Congress of the Confederation endorsed a plan to revise the Articles of Confederation on February 21, 1787.[17] The plan called on each state legislature to send delegates to a convention “’for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation’ in ways that, when approved by Congress and the states, would ‘render the federal constitution adequate to the exigencies of government and the preservation of the Union.’”[19]

the nationalists organize -

Geo: Washington, American

Convention President

prestige brought delegates -

Nathaniel Gorham, Ma

'Committee of the Whole'

Chair - ran daily business -

George Wythe, Va

Chair, Rules Committee

delegates consult, not states -

William Jackson, SC

Convention Secretary

Society of the Cincinnati

To amend the Articles into a workable government, 74 delegates from the twelve states were named by their state legislatures; 55 showed up, and 39 eventually signed. [20] On May 3rd, eleven days early, James Madison arrived to Philadelphia and met with James Wilson of the Pennsylvania delegation to plan strategy. Madison outlined his plan in letters that (1) State legislatures each send delegates, not the Articles Congress. (2) Convention reaches agreement with signatures from every state. (3) The Articles Congress approves forwarding it to the state legislatures. (4) The state legislatures independently call one-time conventions to ratify, selecting delegates by each state’s various rules of suffrage. The Convention was to be "merely advisory" to the people voting in each state.[21]

Convening

George Washington arrived on time, Sunday, the day before scheduled opening. His participation lent his prestige to the proceedings, attracting some of the best minds in America.[22] For the entire duration of the Convention, Washington was a guest at the home of Robert Morris, Congress’ financier for the American Revolution and a Pennsylvania delegate. William Jackson, in two years to be the president of the Society of the Cincinnati, had been Morris' agent in England for a time. He won election as a non-delegate to be the Convention Secretary over Benjamin Franklin's grandson. Morris entertained among the delegates lavishly.

The convention was scheduled to open May 14, but only Pennsylvania and Virginia delegations were present. The Convention was postponed until a quorum of seven states gathered on Friday the 25th.[23]

The Philadelphia Convention

George Washington, the President of the Convention,

will later become the first President of the United StatesGeorge Washington was elected the Convention president, and Chancellor (judge) George Wythe (Va) was chosen Chair of the Rules Committee. The rules of the Convention were published the following Monday.[24] Nathaniel Gorham (Ma) was elected Chair of the "Committee of the Whole", a parliamentary situation where individuals spoke freely, and votes could be retaken to allow for bargaining. Provisions in the draft articles were repeatedly made, reconnected and remade as the order of business proceeded. The Convention officials and procedures were in place before arrival of nationalist opponents such as John Lansing (NY) and Luther Martin (Md).[25] By the end of May, the stage was set.

The Constitutional Convention voted to keep the debates secret so that the delegates could speak freely, negotiate, compromise and change. Both House of Commons and the colonial assemblies were secret. Debates of the Articles Congress were not reported. Yet since the proposal was for fundamental change from a confederation to a new, consolidated yet federal government, the surprise itself made Convention secrecy a major issue in the very public debates leading up to the crowd-filled ratification conventions.[26] Nevertheless, delegates continued in positions of public trust. Of those participating in the Convention, ten members would also number in the 33 chosen by their state legislatures for the Articles Congress that September.[27]

Outside the Convention in Philadelphia, there was a national convening of the Society of the Cincinnati. Washington was said to be embarrassed. The 1776 “old republican” delegates like Elbridge Gerry (Ma) found anything military or hereditary anathema. The Presbyterian Synod of Philadelphia and New York convention was meeting to redefine its Confession, dropping the faith requirement for civil authority to prohibit false worship.[28] Protestant Episcopalian Washington attended a Roman Catholic Mass and dinner.[29] Revolution veteran Jonas Phillips, of the Mikveh Israel Synagogue, petitioned the Convention to avoid a national oath for both Old and New Testaments.[30] Merchants of Providence, Rhode Island, petitioned for consideration, even though their Assembly had not sent a delegation. Congregational minister Manasseh Cutler, former Army chaplain from Massachusetts arrived into town from New York, flush with his lobbying victory during the Northwest Ordnance negotiations in the Articles Congress. He carried grants of five million acres to parcel out among The Ohio Company and “speculators”, some of whom would be found among the delegates.[31] Noah Webster staying in Philadelphia, would write a pamphlet as “A Citizen of America” in October. Immediately after the signing, "Leading Principles of the Federal Convention" advocated adoption of the Constitution. It was published much earlier and more widely circulated than today's better known Federalist Papers.[32]

Agenda

Every few days, new delegates arrived, happily noted in Madison’s Journal. But as the Convention went on, individual delegate coming and going meant that a state's vote could change with the change of delegation composition. The volatility added to the inherent difficulties, making for an “ever-present danger that the Convention might dissolve and the entire project be abandoned.”[33]

nationalist floor leaders from biggest states

most speeches, they seconded one another's motions-

James Madison, Va

strategy, comparative study

'Father of the Constitution' -

James Wilson, Pa

westerly practice, lands

”unsung hero of Convention”

Although twelve states sent delegations, there were never more than eleven represented in the floor debates, often fewer. State delegations absented themselves at votes different times of day. There was no minimum for a state delegation; one would do. Daily sessions would have thirty members present. Members came and went on public and personal business. The Articles Congress was meeting at the same times so members would absent themselves to New York City on Congressional business for days and weeks at a time.[34]

But the work before them was continuous, even if attendance was not. The Convention resolved itself into a “Committee of the Whole”, and could remain so for days. It was informal, votes could be taken and retaken easily, positions could change without prejudice, and importantly, no formal quorum call was required. The nationalists were resolute. As Madison put it, the situation was too serious for despair. [35]

They used the same State House as the Declaration signers. The building setback from the street was still dignified, but the “shaky” steeple was gone. The summer was hot, but city hand-pump wells were nearby. Flies were thick and nearby building construction made the street noisy. Sessions followed the customary six-day work week. Breakfast was before sunup. The Hall was still cool at ten, but hot by noon. Delegates sweltered in the closed room for secrecy, sentries kept passers-by from under the windows. After three, Delegates usually adjourned for dinner, or escaped into the green countryside, or along miles of riverside quays for offshore breezes.[36] When they adjourned each day, they lived in nearby lodgings, as guests, roomers or renters. They ate supper with one another in town and taverns, “often enough in preparation for tomorrow’s meeting.”[37]

national plans v. federal plans

re-constitution of a republican legislature-

Edmund Randolph, Va

bicameral: people elect both

consolidated government -

Benj: Franklin, American

unicameral: people only elect

populations equal -

Roger Sherman, Ct

Senate: states; House: people: Great Compromise

Delegates reporting to the Convention presented their credentials to the Secretary, Major William Jackson of South Carolina. The state legislatures of the day used these occasions to say why they were sending representatives abroad. New York thus publically enjoined its members to pursue all possible “alterations and provisions” for good government and “preservation of the Union”. New Hampshire called for “timely measures to enlarge the powers of Congress”. Virginia stressed the “necessity of extending the revision of the federal system to all its defects”. [38]

On the other hand, Delaware categorically forbade any alteration of the Articles one-state, equal vote, one-vote-only provision in the Articles Congress.[39] The Convention would have a great deal of work to do to reconcile the many expectations in the chamber. At the same time, delegates wanted to finish their work by fall harvest and its commerce.[40]

Current knowledge of drafting the Constitution comes primarily from the Journal left by James Madison,[41] It can be found chronologically incorporated in “The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787”, edited by Max Farrand, available online. [42] The source documents are organized by date including those from the Convention Journal, Rufus King (Ma), and James McHenry (Md), along with later Anti-federalists Robert Yates (NY), and William Paterson (NJ). Farrand corrects errors among revisions that Madison made to his Journal while in his seventies.[43]

The Virginia Plan[41] proposed by Governor Edmund Randolph (Va) was the unofficial agenda for the Convention. It was weighted toward the interests of the larger, more populous states. Provisions of this "Randolph Plan" including the following: (1) A bicameral legislature of a House proportioned to population and variable state representation in a Senate (2) An executive chosen by the national legislature, (3) A judiciary, with life-terms of service and vague powers, (4) The national legislature would be able to veto state laws.[44]

An alternative proposal, William Paterson's New Jersey Plan, contained proposals geared toward smaller states: (1) A unicameral national legislature with each state legislature sending an equal number to represent it, (2) An executive branch appointed by the legislature, and (3) A judicial branch appointed by the executive.[45]

Slavery in debate

Main article: Slavery in the United StatesThe contentious issue of slavery was too controversial to be resolved during the Convention. The issue of slavery, although always an undercurrent during deliberations and side-discussions, was at center stage in the Convention three times, June 7 regarding who would vote for Congress, June 11 in debate over how to proportion relative seating in the ‘house’, and August 22 relating to commerce and the future wealth of the nation.

slavery issue in Convention:

regulation, not abolition-

George Mason, Va

abolitionist

for national regulation -

Charles Pinkney, SC

justified slavery

for state regulation -

Oliver Ellsworth, Ct

rich parts = rich whole

for state regulation

Eighteenth Century America had the widest franchise of any nation of the world. But it was a society of its time. Property gave a man “a stake in society, made him responsible, worthy of a voice, and with enough taxable property, eligible for office holding. Many could vote because most property was held as family farms. Though a substantial part of wealthy white America rested on slavery as property, the Convention met, not to reform society, but to create government for society as it existed. In determining who should vote, the property requirements among the states could not be reconciled. Pennsylvania, Delaware and New Hampshire were already for abolishing property requirements. To allow all states their own rules of suffrage, the Constitution was written with no property requirements. Slavery was taken out of that equation after the debate June 7. [46]

Once the Convention turned to how to proportion the House representation, tempers among several delegates exploded over slavery again. If the number of seats depended on wealth, Pierce Butler (SC) wanted to include slaves. Elbridge Gerry (Ma) answered that the South could not have it both ways, if slaves were property and to be counted for Congress, then the North could count horses and cows. The attacks turned pointedly personal. Benjamin Franklin (Pa) interrupted with a speech about dividing up Pennsylvania so state populations were more nearly equal. He took some time. No vote was taken, tempers cooled, and the three-fifths non-free population count proposed by J. Wilson (Pa) passed using the Articles Congress “federal ratio”.[47]

On August 6, the Committee of Detail reported its revisions to the Randolph Plan. A preamble was drafted. Delegates turned their thoughts to political economy that might best secure the public welfare and general happiness in the long run, for posterity. Again the question of slavery came up, and again it was met with attacks of moral outrage, relative poverty of the whites, and they were answered by appeals to local wealth by local means, and southern delegates inability to carry ratification in their states if slavery were threatened. By August 22, the delegates wove a web of mutual compromises relating to commerce and trade, north and south, port-states and landlocked, slave-holding, and free, relating to navigation laws, import taxes, population counts, national regulation of western territories and trade on the Mississippi. The transfer of power to regulate slave trade from states to central government could happen in 20 years, but only if there were national majorities for it both among the states in the 'senate' and among the people in the 'house', when it came time, then.[48] Later generations could try out their own answers. The delegates were trying to make a government that might last that long.[49]

Aiding slave escape. Freedmen in Revolutionary generation were motivated by kinship ties[50] The Constitution’s Section 9 of Article I allowed the continued “migration” of the free or “importation” of indentures and slaves as the states chose, defining slaves as persons, not property. Article 1, section 2, provided for long-term power to flow to states with increasing population, away from those decreasing. That change would be counted in a census every ten years. Apportionment in the House of Representatives would not be by any wealth as initially allowed in the Randolph Plan. It would be representing people, the count to be made of the free citizens and other persons. [51] To the whole number of men and women, free and indentured, would be added “three-fifths” the number of “other persons”, meaning propertyless slaves and taxed Indian farming families.[52]

Article V prohibited any amendments or legislation changing the provision regarding slave importation until 1808, thereby giving the States then existing 20 years to resolve this issue. As the date neared in 1806, President Thomas Jefferson sent a message to the House and Senate congratulating the 9th Congress on their constitutional opportunity to remove U.S. citizens from the transatlantic slave trade which was perpetrating “violations of human rights … on the unoffending inhabitants of Africa”.[53] Signed into law March 3, 1807, The "Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves" took effect the fist instant the Constitution allowed, January 1, 1808. The United States would join the British Parliament, that year in the first “international humanitarian campaign”.[54]

Just as the abolitionist George Mason refused to sign the Constitution, in the ratification conventions of Massachusetts and Virginia, the anti-slavery delegates began as anti-ratification votes. Still, the Constitution "as written" was an improvement over the Articles from an abolitionist point of view. In the Massachusetts Ratification Convention, Federalist anti-slavery delegate Isaac Backus confronted abolitionist Anti-Federalist Thomas Dawes. Trying to gain his support for adoption, he reasoned that the Constitution provided for abolition of the slave trade but the Articles did not. Sometimes those opposed to slavery were persuaded that the evils of a broken Union would bring worse consequences than allowing the fate of slavery to be determined gradually over time. [55] Sometimes contradictions among opponents were used to try to gain abolitionist converts. In Virginia’s Ratification Convention, Federalist George Nicholas dismissed fears on both sides. Objections to the Constitution were inconsistent, “At the same moment it is opposed for being promotive and destructive of slavery!” [56] But the contradiction was never resolved peaceably, and the failure to do so contributed to the Civil War.[57]

"Great Compromise"

Roger Sherman (CT), although something of a political broker in Connecticut, was an unlikely leader in the august company of the Convention.[58] Arriving right behind the nationalist leaders on May 30, Sherman was reported to prefer a “patch up” of the existing Confederacy.[59] Another small state delegate, George Read (DE) agreed with the nationalists that state legislatures were a national problem. But rather than see larger states overshadow the small, he’d prefer to see all state boundaries erased. Big-state versus small-state antagonisms hardened early.[60]

On June 11, Roger Sherman proposed his first version of the Convention’s “Great Compromise”. It was like the proposal he made in the 1776 Continental Congress. Representation in Congress should be both by states and by population. There, he was voted down by the small states in favor of all states equal, one vote only.[61] Now in 1787 Convention, he wanted to balance all the big-state victories for population apportionment. He proposed that in the second ‘senate’ branch of the legislature, each state should be equal, one vote and no more.[62] Sherman argued that the bicameral British Parliament had a House of Lords equal with the House of Commons to protect their propertied interests apart from the people. He was voted down, this time by the big states.[63] The motion for equal state representation in a ‘senate’ failed: 6 against, 5 for.[64]

"men of original principles"

equality of the states-

Luther Martin, Md

if not state equality

create regional nations -

Gunning Bedford, De

if not state equality, get a foreign power of “good faith” -

Elbridge Gerry, Ma

if not state equality, a foreign power will conquer us

Friday, June 15 Paterson introduced his New Jersey Plan. The “old patriots” of 1776 and the “men of original principles” had organized.[65] Roger Sherman (Ct), a signer of the Declaration of Independence, was with them. John Lansing (NY) observed that the Paterson Plan “sustained the sovereignty of the states”, while that of Mr. Randolph destroyed state sovereignty in a national, consolidated government. William Paterson (NJ) attacked the nationalists. The Convention had no authority to propose anything not sent up from state legislatures, and the states were not likely to adopt anything new. James Wilson (PA) answered, The Convention could not conclude anything, but it could recommend anything.[66]

Lansing (NY) had objected that if the New York legislature knew anything about proposals for consolidated government, it would not have sent anyone. Edmund Randolph (Va) countered, With the salvation of the American republic at stake, it would be treason to withhold any proposal believed necessary for good government and the Union.[67] Three sessions after its introduction, Paterson’s plan was off the table. It failed : 7 against, 3 for, 1 divided.[68] For nearly a month there was no progress; small states were seriously thinking of walking out of the Convention.[69]

In a related resolution, the "original principles" men won a victory on June 25. The ‘senate’ would be chosen by the state legislatures, not the people, passed: 9 for, 2 against. [70] On June 27, the basis of representation for both the ‘house’ and the ‘senate’ re-surfaced. Roger Sherman (Ct) tried a second time to get his idea for a ‘house’ on the basis of population and a ‘senate’ on an equal states basis. The big state delegates beat him again. The 'house' would be chosen directly by the population voting. On the motion for equal state representation in the 'senate', the majority simply adjourned “before a determination was taken in the House.” [71] Luther Martin (Md) insisted that he would rather live under a regional government than submit to a United States under the Randolph Plan.[72]

Sherman’s proposal came again two days later for the third time from Oliver Ellsworth (CT). In the ‘senate’, the states should have equal representation. If this cannot be agreed to, somehow, the union of states would end up separated. Wilson (Pa) countered, the purpose of population apportionment was not to make big states powerful, it was to “tear down a rotten house” of equal state representation.[73] Gunning Bedford (DE) spoke hotly, “I do not, gentlemen, trust you.” If the equal-state principle was lost, the small states could confederate with a foreign power showing “more good faith”. Elbridge Gerry (MA) warned, If the states cannot unite themselves, being conquered by “some foreign sword will probably do the work for us”.[74] On June 29, the majority running things, the Convention adjourned “before a determination was taken in the House.” on the question of equal state representation.[75]

On July 2, the Convention for the fourth time considered a ‘senate’ with equal state votes. This time a vote was taken, but it stalled again, tied at 5 yes, 5 no, 1 divided. The Convention elected one delegate from each state onto a Committee to make a proposal; it reported July 5.[76] Nothing changed over five days. July 10, Lansing and Yates (NY) quit the Convention in protest.[77] No direct vote on the basis of ‘senate’ representation was pushed on the floor for another week.

But the first new ‘house’ seat apportionment was agreed, balancing big and small, north and south. The big states got a decennial census for 'house' apportionment to reflect their future growth. Northerners had insisted on counting only free citizens for the ‘house’; southern delegations wanted to add property. Benjamin Franklin's compromise was that there would be no “property” provision to add representatives, but states with large slave populations would get a bonus added to their free persons by counting three-fifths other persons.[78]

On July 16, Sherman’s “Great Compromise” prevailed on its fifth try. Every state was to have equal numbers in the United States Senate.[79] Washington ruled it passed on the vote 5 yes, 4 no, 1 divided, using precedent established in the Convention earlier.[80] Now some of the big-state delegates talked of walking out, but none did. Debate over the next ten days developed an agreed general outline for the Constitution.[81] Small states readily yielded on many questions. Most remaining delegates, big-state and small, now felt safe enough to chance a new plan.[82]

Two new branches

The Constitution innovated two branches of government that were not a part of the U.S. government during the Articles of Confederation. Previously, a thirteen member committee had been left behind when Congress adjourned to carry out the "executive" functions. Suits between states were referred to the Articles Congress, and treated as a private bill to be determined by majority vote of members attending that day.

President, the national "chief magistrate" -

John Dickinson, De

for one-person president -

Luther Martin, Md

for 3-person presidency

On June 7, the “national executive” was taken up in Convention. The “chief magistrate”, or ‘presidency’ was of serious concern for a formerly colonial people fearful of concentrated power in one person. But to secure a "vigorous executive", nationalist delegates such as James Wilson (Pa), Charles Pinckney (SC), and John Dickenson (De) favored a single officer. They had someone in mind whom everyone could trust to start off the new system, George Washington.

After introducing the item for discussion, there was a prolonged silence. Benjamin Franklin (Pa) and John Rutledge (SC) had urged everyone to speak their minds freely. When addressing the issue with George Washington in the room, delegates were careful to phrase their objections to potential offenses by officers chosen in the future who would be 'president' "subsequent" to the start-up. Roger Sherman (Ct), Edmund Randolph (Va) and Pierce Butler[83] (SC) all objected, preferring two or three persons in the executive, as had the ancient Roman Republic.

Nathaniel Gorham was Chair of the Committee of the Whole. The vote for a one-man ‘presidency’ carried 7-for, 3-against, New York, Delaware and Maryland in the negative. George Washington, sitting in the Virginia delegation, voted yes. With that vote for a single ‘presidency’, George Mason (Va) gravely considered the Confederation’s “federal government as in some measure dissolved by the meeting of this Convention.” [84]

Judiciary, the national court(s) -

John Rutledge, SC

Supreme Court only

state power, lower spending -

Rufus King, Ma

district court = variation

regional court, fewer appeals

The Convention was following the Randolph Plan, taking each resolve in turn when it moved forward. They returned to items when overnight coalitions required adjustment to previous votes to secure a majority on the next item of business. June 19, the Ninth Resolve on the national court system, and the nationalist proposal for the inferior (lower) courts.

Pure 1776 republicanism had not given much credit to judges, who would set themselves up apart from and sometimes contradicting the state legislature, the voice of the sovereign people. Under the precedent of English Common Law according to William Blackstone, the legislature, following proper procedure, was for all constitutional purposes, “the people.” This dismissal of unelected officers sometimes took an unintended turn among the people. One of John Adams clients believed the First Continental Congress in 1775 had assumed the sovereignty of Parliament, and so abolished all previously established courts in Massachusetts.[85]

In the Convention, looking at a national system, Judge Wilson (Pa) sought appointments by a single person to avoid legislative payoffs. Judge Rutledge (SC) was against anything but one national court, a Supreme Court to receive appeals from the highest state courts, like the South Carolina court he presided over as Chancellor. Rufus King (Ma) thought national district courts in each state would cost less than appeals that otherwise would go to the ‘supreme court’ in the national capital. National inferior courts passed but making appointments by ‘congress’ was crossed out and left blank so the delegates could take it up later after “maturer reflection.” [86]

Re-allocate power

Main article: Federalism in the United StatesThe Constitutional Convention created a new, unprecedented form of government by reallocating powers of government. Every previous national authority had been either a centralized government, or a “confederation of sovereign constituent states.” The American power-sharing was unique at the time. The sources and changes of power were up to the states. The foundations of government and extent of power came from both national and state sources. But the new government would have a national operation. [87] To meet their goals of cementing the Union and securing citizen rights, Framers allocated power among executive, senate, house and judiciary of the central government. But each and every state government in their variety continued exercising powers in their own sphere.[88]

Increase Congress

The Convention did not start with national powers from scratch, it began with the powers already vested in the Articles Congress with control of the military, international relations and commerce.[89] The Constitution added ten more. Five were minor relative to power sharing, including business and manufacturing protections.[90] One important new power authorized Congress to protect states from the “domestic violence” of riot and civil disorder, but it was conditioned by a state request. [91]

The Constitution increased Congressional power to organize, arm and discipline the state militias, to use them to enforce the laws of Congress, suppress rebellions within the states and repel invasions. But the Second Amendment would ensure that Congressional power could not be used to disarm state militias.[92]

Taxation substantially increased the power of Congress relative to the states. It was limited by restrictions, forbidding taxes on exports, per capita taxes, requiring import duties to be uniform and that taxes be applied to paying U.S. debt. But the states were stripped of their ability to levy taxes on imports, which was at the time, “by far the most bountiful source of tax revenues”.

Congress had no further restrictions relating to political economy. It could institute protective tariffs, for instance. Congress overshadowed state power regulating interstate commerce; the United States would be the “largest area of free trade in the world.” [93] The most undefined grant of power was the power to “make laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution” the Constitution’s enumerated powers.[94]

Limit governments

As of ratification, sovereignty was no longer to be theoretically indivisible. With a wide variety of specific powers among different branches of national governments and thirteen republican state governments, now "each of the portions of powers delegated to the one or to the other … is … sovereign with regard to its proper objects".[95] There were some powers that remained beyond the reach of both national powers and state powers,[96] so the logical seat of American “sovereignty” belonged directly with the people-voters of each state.[97]

Besides expanding Congressional power, the Constitution limited states and central government. Six limits on the national government addressed property rights such as slavery and taxes.[98] Six protected liberty such as prohibiting ex post facto laws and no religious tests for national offices in any state, even if they had them for state offices.[99] Five were principles of a republic, as in legislative appropriation.[100] These restrictions lacked systematic organization, but all constitutional prohibitions were practices that the British Parliament had “legitimately taken in the absence of a specific denial of the authority.” [101]

The regulation of state power presented a “qualitatively different” undertaking. In the state constitutions, the people did not enumerate powers. They gave their representatives every right and authority not explicitly reserved to themselves. The Constitution extended the limits that the states had previously imposed upon themselves under the Articles of Confederation, forbidding taxes on imports and disallowing treaties among themselves, for example.[102]

In light of the repeated abuses by ex post facto laws passed by the state legislatures, 1783-1787, the Constitution prohibited ex post facto laws and bills of attainder to protect United States citizen property rights and right to a fair trial. Congressional power of the purse was protected by forbidding taxes or restraint on interstate commerce and foreign trade. States could make no law “impairing the obligation of contracts.”[103] To check future state abuses the framers searched for a way to review and veto state laws harming the national welfare or citizen rights. They rejected proposals for Congressional veto of state laws and gave the Supreme Court appellate case jurisdiction over state law because the Constitution is the supreme law of the land.[104] The United States had such a geographical extent that it could only be safely governed using a combination of republics. Federal judicial districts would follow those state lines.[105]

Population power

The British had relied upon a concept of “virtual representation” to give legitimacy to their House of Commons. It was not necessary to elect anyone from a large port city, or the American colonies, because the representatives of “rotten boroughs”, the mostly abandoned medieval fair towns with twenty voters, "virtually represented" thriving mercantile ports such as Birmingham’s tens of thousands. Philadelphia in the colonies was second in population only to London.[106]

They were all Englishmen, supposed to be a single people, with one definable interest. Legitimacy came from membership in Parliament of the sovereign realm, not elections from people. As Blackstone explained, the Member is “not bound … to consult with, or take the advice, of his constituents.” As Constitutional historian Gordon Wood elaborated, “The Commons of England contained all of the people’s power and were considered to be the very persons of the people they represented.” [107]

While the English “virtual representation” was hardening into a theory of Parliamentary sovereignty, the American theory of representation was moving towards a theory of sovereignty of the people. In their new constitutions written since 1776, Americans required community residency of voters and representatives, expanded suffrage, and equalized populations in voting districts. There was a sense that representation “had to be proportioned to the population.” [108] The Convention would apply the new principle of "sovereignty of the people" both to the House of Representatives, and to the United States Senate.

House changes. Once the Great Compromise was reached, delegates in Convention then agreed to a decennial census to count the population. The Americans themselves did not allow for universal suffrage for all adults.[109] Their sort of "virtual representation" said that those voting in a community could understand and themselves represent non-voters when they had like interests that were unlike other political communities. There were enough differences among people in different American communities for those differences to have a meaningful social and economic reality. Thus New England colonial legislatures would not tax communities which had not yet elected representatives. When the royal governor of Georgia refused to allow representation to be seated from four new counties, the legislature refused to tax them.[110]

The 1776 Americans had begun to demand expansion of the franchise, and in each step, they found themselves pressing towards a philosophical “actuality of consent.” [111] The Convention determined that the power of the people, should be felt in the House of Representatives. Regardless of state heritage, militias or amassed wealth they would be counted, increasing and decreasing in their state communities. They would be counted by populations[112] every ten years, the decennial census.

Senate changes. The Convention found that it was harder trying to give expression to the will of the people in new states. Virginia Resolves ‘ten’ was agreed to without dissent, “that provision ought to be made for the admission of States lawfully arising within the limits of the United States.” Then the debate began as to what state, if any, might be “lawfully arising” states outside the boundaries of the existing confederated thirteen states. [113]

new states or provinces forever

for the people moving into new territory-

G. Morris, (Pa)

make them provinces -

Elbridge Gerry, (Ma)

they will “enslave” us -

Luther Martin, (Md)

they’ll start a civil war -

George Clymer, (Pa)

its “suicide” for our 13

The new government was like the old, to be made up of pre-existing states. Now there was to be admission of new states. Regular order would provide new states by state legislatures for Kentucky out of Virginia, Tennessee from North Carolina, Maine of Massachusetts. But the Articles Congress by its Northwest Ordnance presented the Convention another issue by its promise to settlers in the Northwest Territory. Land was sold to them by contract, they were to have all rights of U.S. citizenship, and they might one day constitute themselves into “no more than five” states. More difficult still, most delegates anticipated adding alien peoples of Canada, Louisiana and Florida to United States territory.[114]

G. Morris (Pa) was reluctant to expand into any so “remote wilderness”, it would retard the commercial development of the east. Western peoples were the least desirable, least governable he knew. He would bar them from statehood forever, make them into perpetual provinces. He did not have the votes in Convention, but he made it possible in the future by giving Congress power to regulate and dispose of U.S. territory or other property.[115] For Elbridge Gerry (Ma), any new unknown states could be a majority in the Senate when they outnumbered the original thirteen states, and that would be intolerable. They would feel their power and abuse it, they would “enslave” the original thirteen. They would come “under some foreign influence” like the Spanish funded the Creek Indians to attack the east, and the British funded the Iroquois. “Foreign gold” would corrupt their state legislatures.

On his return home, Luther Martin (Md) argued that westerners could not reasonably tolerate suffering under the dominance of eastern states. They would be justified in civil war to “shake off so ignominious a yoke.” G. Morris (Pa) had it that if they were allowed to be states, westerners would drag the country into an inevitable war with Spain for the Mississippi River, involving the whole continent. [116] These were poor people. How could they pay their fair share of taxes to the Union, or even pay for their own militia to defend against Amerindian nations? Were there to be so many western states that these poor and ignorant would outvote the eastern maritime states in the Senate? The east needed a way to protect its own interest, Nathaniel Gorham (Ma) suggested giving out representation to the west only as it suited the east. George Clymer (Pa), an “old patriot” of ’76, thought the whole western state idea was “suicide” for the original states. [117] Roger Sherman (Ct) countered that the people of the west would be “our children and our grandchildren.” Elbridge Gerry (Ma) retorted some of those grandchildren would be left behind, and they had interests too. There were so many foreigners moving out west, it could not be certain how things would turn out. [118]

East-west jealousies were very much alive in the Convention. Delegates knew of them and benefitted from them. In Pennsylvania, Virginia and the Carolinas, state legislatures enshrined inequality of east-west representation in their state constitutions. Massachusetts and New York had in their past. [119] Virginia's Thomas Jefferson, absent the Convention, would complain that it took 15 voting men west of the Blue Ridge Mountains to equal one man east. Representative pportionment for states with a western “back-country” was a mix of population, voters and property. That status quo was captured in the original Randolph Plan for apportionment by “population or property” for both the ‘house’ and the ‘senate’. Instead, the Convention chose a formula for representing people as in a democracy.</ref> The demographic world of the states was changing underfoot. Populations were rapidly deploying west in such numbers, that delegates from Rhode Island and Massachusetts complained of the persistent interest in westward expansion. [120]

But in the light of the debate over new states from western territories, delegates had pause over the number agreed to for House representation, 40,000 might be too small, too easy for the westerners. “States” had been declared out west already. They called themselves republics, and set up their own courts directly from the people without colonial charters from the sovereign states. In Transylvania, Westsylvania, Franklin, Vandalia, “legislatures” met with emissaries from British and Spanish Empires in violation of the Articles of Confederation, just as the sovereign states had done. Luther Martin (Md) stopped that claim by ensuring that the United States owned all the backlands ceded by the states.[121] He was successful in delivering a provision in the final draft of the Constitution, no majorities in Congress could break up the larger states without their consent.[122]

James Wilson (Pa) had no fear of western states achieving a majority one day. The majority should rule. The British were jealous of our growth, and sought to curb it. That brought our hate, then our separation. If we follow the same rule, we will get the same results. Congress has never been able to discover a better rule than majority rule. Madison (Va) was of the “firm opinion” that there could be no discrimination against the west. And as they grow, all their trade goes by New Orleans. Imposts will more surely be collected there. Until then, they must get all their supplies from eastern businesses. Character is not determined by points of a compass. States admitted are equals, they will be made up of our brethren. George Mason (Va) reasoned that we must commit to right principles, even if the right way one day benefits other states. They will be free like ourselves, their pride will not allow anything but equality. [123] It was at this time in the Convention that Reverend Manasseh Cutler arrived to lobby for what he had won in the Articles Congress. He has secured guaranteed protection of contracts in western land sales. He brought acres of land grants to parcel out. Their sales would fund most of the U.S. government expenditures for its first few decades. There were allocations for the Ohio Company stockholders at the Convention, and for others delegates too. In December, 1787, good to his word, Cutler led a small band of pioneers into the Ohio Valley.[124]

The provision for admitting new states became relevant at the purchase of Louisiana It was constitutionally justifiable under the "Treaty Making" power of the Federal government. The agrarian advocates sought to make the purchase of land that had never been administered, conquered, or formally ceded to any of the original thirteen states. Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans would divide the Louisiana Purchase into states, speeding land sales to finance the Federal government with no new taxes. There would be no war for the possession of the Mississippi River. The new populations of new states would swamp the commercial states in the Senate. They would populate the House with egalitarian Democrat-Republicans to overthrow the Federalists.[125] Jefferson dropped the proposal of Constitutional Amendment to permit the Purchase, and with it, his notion of a confederation of sovereign states.[126]

Ratification and beginning

On September 17, 1787, the Constitution was completed, followed by a speech given by Benjamin Franklin. Franklin urged unanimity, although the Convention had decided only nine state ratification conventions were needed to inaugurate the new government. The Convention submitted the Constitution to the Congress of the Confederation.[44]

ratification conventions in the states

more nearly "the people"-

Rufus King, Ma

For ratifying Constitution, influenced VA & NY -

Luther Martin, Md

"Anti" in Articles Congress,

lost “Amend Articles" vote -

Patrick Henry, Va

"Anti" like those in MA, NY, SC, lost "Amend before" vote -

James Madison, Va

pushed "Amendments after", the Bill of Rights

Massachusetts’s Rufus King assessed the Convention as a creature of the states, independent of the Articles Congress, submitting its proposal to Congress only to satisfy forms. Though amendments were debated, they were all defeated. On September 28, 1787, the Articles Congress resolved “unanimously” to transmit the Constitution to state legislatures for submitting to a ratification convention according to the Constitutional procedure.[127] Several states enlarged the numbers qualified just for electing ratification delegates. In doing so, they went beyond the Constitution's provision for the most voters for the state legislature to make a new social contract among, more nearly than ever before, "We, the people".[128]

Following Massachusetts's lead, the Federalist minorities in both Virginia and New York were able to obtain ratification in convention by linking ratification to recommended amendments.[129] A minority of the Constitution’s critics continued to oppose the Constitution. Maryland’s Luther Martin argued that the federal convention had exceeded its authority; he still called for amending the Articles.[130] Article 13 of the Articles of Confederation stated that the union created under the Articles was "perpetual" and that any alteration must be "agreed to in a Congress of the United States, and be afterwards confirmed by the legislatures of every State".[131]

However, the unanimous requirement under the Articles made all attempts at reform impossible. Martin’s allies such as New York’s John Lansing, Jr., dropped moves to obstruct the Convention's process. They began to take exception to the Constitution “as it was”, seeking amendments. Several conventions saw supporters for "amendments before" shift to a position of "amendments after" for the sake of staying in the Union. New York Anti’s “circular letter” was sent to each state legislature proposing a second constitutional convention for "amendments before". It failed in the state legislatures. Ultimately only North Carolina and Rhode Island would wait for amendments from Congress before ratifying.[129]

Ratification of the Constitution

-- dates, states and votes --Date State Votes Yes No 1 December 7, 1787 Delaware 30 0 2 December 11, 1787 Pennsylvania 46 23 3 December 18, 1787 New Jersey 38 0 4 January 2, 1788 Georgia 26 0 5 January 9, 1788 Connecticut 128 40 6 February 6, 1788 Massachusetts 187 168 7 April 26, 1788 Maryland 63 11 8 May 23, 1788 South Carolina 149 73 9 June 21, 1788 New Hampshire 57 47 10 June 25, 1788 Virginia 89 79 11 July 26, 1788 New York 30 27 12 November 21, 1789 North Carolina 194 77 13 May 29, 1790 Rhode Island 34 32 Article VII of the proposed constitution stipulated that only nine of the thirteen states would have to ratify for the new government to go into effect for the participating states.[1] After a year had passed in state-by-state ratification battles, on September 13, 1788, the Articles Congress certified that the new Constitution had been ratified. The new government would be inaugurated with eleven of the thirteen. The Articles Congress directed the new government to begin in New York City on the first Wednesday in March, [132] and on March 4, 1789, the government duly began operations.

George Washington had earlier been reluctant to go the Convention for fear the states “with their darling sovereignties” could not be overcome.[133] But he was elected the Constitution's President unanimously, including the vote of Virginia’s presidential elector, the Anti-federalist Patrick Henry.[134] The new Congress was a triumph for the Federalists. The Senate of eleven states would be 20 Federalists to two Virginia (Henry) Anti-federalists. The House would seat 48 Federalists to 11 Antis from only four states: Massachusetts, New York, Virginia and South Carolina.[135]

Antis' fears of personal oppression by Congress were allayed by Amendments passed under the floor leadership of James Madison in the first session of the first Congress. These first ten Amendments became known as the Bill of Rights. [136] Objections to a potentially remote federal judiciary were reconciled with 13 federal courts (11 states, Maine and Kentucky), and three Federal riding circuits out of the Supreme Court: Eastern, Middle and South.[137] Suspicion of a powerful federal executive was answered by Washington’s cabinet appointments of once-Anti-Federalists Edmund Jennings Randolph as Attorney General and Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State.[138][139]

What Constitutional historian Pauline Maier calls a national “dialogue between power and liberty” had begun anew. [140]

Historical influences

Fundamental law

Several ideas in the Constitution were new. These were associated with the combination of consolidated government along with federal relationships with constituent states.

rule of law by Enlightenment and Common Law -

John Locke

Two Treatises of Government

life, liberty and property -

Edward Coke

Institutes of the Laws

equity and habeas corpus -

Montesquieu

The Spirit of the Laws

public virtue; three branches -

William Blackstone

Commentaries on the Laws

enacted law; property rights

The due process clause of the Constitution was partly based on common law stretching back to Magna Carta (1215).[44] The document established the principle that the Crown's powers could be limited.

The "law of the land" was the King in Parliament of Lords and Commons. The once sovereign King was to be bound by law. Magna Carta as "sacred text" would become a foundation of English liberty against arbitrary power wielded by a tyrant.

Both the influence of Edward Coke and William Blackstone were evident at the Convention.

In his Institutes of the Laws of England, Edward Coke interpreted Magna Carta protections and rights to apply not just to nobles, but to all British subjects of the Crown equally. Coke extended this principle overseas to colonists. In writing the Virginia Charter of 1606, he enabled the King in Parliament to give those to be born in the colonies all rights and liberties as though they were born in England.

William Blackstone saw the Parliament as legislature, the representative of the people, and so sovereign over judges in equity law. In his "Commentaries on the Laws of England" discussing cases, where ruling judges provided no rationale, he wrote one so as to connect and relate law and cases to one another in a way that had not been done so extensively before. "Commentaries" were the most influential books on law in the new republic among both lawyers generally and judges.

The most important influence from the European continent was from Enlightenment thinkers John Locke and the brilliant Montesquieu.

British political philosopher John Locke following the Glorious Revolution was a major influence expanding on the contract theory of government advanced by Thomas Hobbes. Locke advanced the principle of consent of the governed in his "Two Treatises of Government". Government's duty in a social contract with the sovereign people was to serve them by protecting their rights. These basic rights of English and by extension all humanity, were life, liberty and property.

Montesquieu, emphasized the need to have balanced forces pushing against each other to prevent tyranny. (This in itself reflects the influence of Polybius's 2nd century BC treatise on the checks and balances of the constitution of the Roman Republic.) In his "The Spirit of the Laws", Montesquieu argues that the separation of state powers should be by its service to the people's liberty: legislative, executive and judicial. The actuating spring driving an aristocracy is excellence and honor, the despot requires compliance and fear. In a democracy the activating spring is public virtue,

Division of power in a republic was informed by the British experience with mixed government, as well as study of republics ancient and modern. A substantial body of thought had been developed from the literature of republicanism in the United States, including work by John Adams. The experiences among the thirteen states after 1776 was remarkably different among those which had been charter, proprietary newly created royal colonies.

Native Americans

The Iroquois nations' political confederacy and democratic government have been credited as influences on the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution.[141][142] Historians debate how much the colonists borrowed from existing Native American models of government. But several founding fathers had contact with Native American leaders and had learned about their styles of government.

-

Red Jacket Iroquois Seneca

council leader, British ally, negotiated with Congress -

Joseph Brant Iroquois Mohawk

war chief, British ally, played U.S. and French for west.

The Iroquois Confederation could not be overlooked. They were “the most powerful Indian group on the continent.” Their government did not always work perfectly, unanimously, but they were once secure within their territory, and had been “nearly invincible” to outsiders over the lifetime of the Convention delegates.[143]

Prominent figures such as Thomas Jefferson in colonial Virginia and Benjamin Franklin in colonial Pennsylvania were involved with leaders of the New York-based Iroquois Confederacy. The English needed allies to check expanding French networks. Both Virginia and Pennsylvania colonial claims extended north and west to Iroquois territory. The English could not expand without somehow bridging the cultural differences antagonizing their Amerindian neighbors.

This concern extended the length of the English settlement, and it motived study of Amerindian culture and governance. John Rutledge of South Carolina in particular is said to have read lengthy tracts of Iroquoian law to the other framers in Convention, beginning with the words, "We, the people, to form a union, to establish peace, equity, and order..."[144]

Even in the 1750s and at the Albany Congress, Benjamin Franklin had seen that no single English colony could effectively deal with Amerindian tribes or expand against the ever-present French. Franklin argued that there should be some sort of diplomatic and self-defense concert among the British colonies. “If the Iroquois could form a powerful union … some kind of union ought not to be beyond the capacity of a dozen English colonies.”[145]

The delegates meeting at Albany were unable to align the independent assemblies that they represented. But seeing the dangers before them, they made recommendations outside proper channels, going over the heads of the colonial legislatures. The Albany Congress went directly to the sovereign Parliament. In this they exceeded their authority, “like those who met at Philadelphia in 1787 would,” when the Constitutional Convention bypassed the independent state legislatures and appealed directly to the sovereign people.[146]

The Iroquois experience with confederacy was both a model and a cautionary tale. Their "Grand Council" had no coercive control over the constituent members. This decentralization of authority and power had frequently plagued the Six Nations since the coming of the Europeans. The governance adopted by the Iroquois suffered from “too much democracy,” among their national parts. Their long term welfare suffered at the hands of French and English intrigues fostered among each separate Iroquois nation.[147]

The new United States faced a diplomatic and military world inhabited by the same Europeans. During the Articles period, individual states had been making separate agreements with European and Amerindian foreign nations apart from Congress. Without the Convention's central government, the framer's feared that the fate of the confederated Articles United States would be the same as the Iroquois Confederacy.

But in its experiment of national self-governance, the Convention relied on past and present. The Constitution used Iroquois and Greek forms of government, Roman and English Common Law, philosophies of republics and the Enlightenment. To commemorate the contribution of Iroquois forms of government to American fundamental law, in October 1988, the U.S. Congress passed Concurrent Resolution 331 to recognize the influence of the Iroquois Constitution upon the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights.[148]

Bills of rights before

The United States Bill of Rights consists of the ten amendments added to the Constitution in 1791, as supporters of the Constitution had promised critics during the debates of 1788.[149] The English Bill of Rights (1689) was an inspiration for the American Bill of Rights. Both require jury trials, contain a right to keep and bear arms, prohibit excessive bail and forbid "cruel and unusual punishments." Many liberties protected by state constitutions and the Virginia Declaration of Rights were incorporated into the Bill of Rights.

Original text

The Constitution consists of a preamble, seven original articles, twenty-seven amendments, and a paragraph certifying its enactment by the constitutional convention.

Authority and purpose

Main article: Preamble to the United States Constitution

opening phrase

inspires friends, provokes opponents.

virtual tour online[150]“ We the People of the United States, - in Order to form a more perfect Union,

- establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility,

- provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare,

- and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity,

do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

” —United States Constitution, Preamble

National government

Legislature

Main article: Article One of the United States Constitution19th Century Growth - government housing its branches Article One describes the Congress, the legislative branch of the federal government. The United States Congress is a bicameral body consisting of two co-equal houses: the House of Representatives and the Senate.

The article establishes the manner of election and the qualifications of members of each body. Representatives must be at least 25 years old, be a citizen of the United States for seven years, and live in the state they represent. Senators must be at least 30 years old, be a citizen for nine years, and live in the state they represent.

Article I, Section 1, reads, "All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives." This provision gives Congress more than simply the responsibility to establish the rules governing its proceedings and for the punishment of its members; it places the power of the government primarily in Congress.

Article I Section 8 enumerates the legislative powers. The powers listed and all other powers are made the exclusive responsibility of the legislative branch:

The Congress shall have power... To make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States, or in any department or officer thereof.

Article I Section 9 provides a list of eight specific limits on congressional power and Article I Section 10 limits the rights of the states.

The United States Supreme Court has interpreted the Commerce Clause and the Necessary and Proper Clause in Article One to allow Congress to enact legislation that is neither expressly listed in the enumerated power nor expressly denied in the limitations on Congress. In McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), the United States Supreme Court fell back on the strict construction of the necessary and proper clause to read that Congress had "[t]he foregoing powers and all other powers..."

Executive

Main article: Article Two of the United States Constitution-

The President’s House

Washington, DC -

James Hoban design

The President’s House

Section analysis Section 1 creates the presidency. The section states that the executive power is vested in a President. The presidential term is four years and the Vice President serves the identical term. This section originally set the method of electing the President and Vice President, but this method has been superseded by the Twelfth Amendment.

- Qualifications. The President must be a natural born citizen of the United States, at least 35 years old and a resident of the United States for at least 14 years. An obsolete part of this clause provides that instead of being a natural born citizen, a person may be a citizen at the time of the adoption of the Constitution. The reason for this clause was to extend eligibility to Citizens of the United States at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, regardless of their place of birth, who were born under the allegiance of a foreign sovereign before the founding of the United States. Without this clause, no one would have been eligible to be president until thirty-five years after the founding of the United States.

United States

This article is part of the series:

Politics and government of

the United StatesLegislaturePresidencyJudiciary

Other countries · Atlas

U.S. Government Portal

- Succession. Section 1 specifies that the Vice President succeeds to the presidency if the President is removed, unable to discharge the powers and duties of office, dies while in office, or resigns. The original text ("the same shall devolve") left it unclear whether this succession was intended to be on an acting basis (merely taking on the powers of the office) or permanent (assuming the Presidency itself). After the death of William Henry Harrison, John Tyler set the precedent that the succession was permanent; this practice was followed when later presidents died in office. Today the 25th Amendment states that the Vice President becomes President upon the death or disability of the President.

- Pay. The President receives "Compensation" for being the president, and this compensation may not be increased or decreased during the president's term in office. The president may not receive other compensation from either the United States or any of the individual states.

- Oath of office. The final clause creates the presidential oath to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution.

Section 2 grants substantive powers to the president:

- The president is the Commander in Chief of the United States Armed Forces, and of the state militias when these are called into federal service.

- The president may require opinions of the principal officers of the federal government.

- The president may grant reprieves and pardons, except in cases of impeachment (i.e., the president cannot pardon himself or herself to escape impeachment by Congress).

Section 2 grants and limits the president's appointment powers:

- The president may make treaties, with the advice and consent of the Senate, provided two-thirds of the senators who are present agree.

- With the advice and consent of the Senate, the President may appoint ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, judges of the Supreme Court, and all other officers of the United States whose appointments are not otherwise described in the Constitution.

- Congress may give the power to appoint lower officers to the President alone, to the courts, or to the heads of departments.

- The president may make any of these appointments during a congressional recess. Such a "recess appointment" expires at the end of the next session of Congress.

Section 3 opens by describing the president's relations with Congress:

- The president reports on the state of the union.

- The president may convene either house, or both houses, of Congress.

- When the two houses of Congress cannot agree on the time of adjournment, the president may adjourn them to some future date.

Section 3 adds:

- The president receives ambassadors.

- The president sees that the laws are faithfully executed.

- The president commissions all the offices of the federal government.

Section 4 provides for removal of the president and other federal officers. The president is removed on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.

Judiciary

Main article: Article Three of the United States ConstitutionArticle Three describes the court system (the judicial branch), including the Supreme Court. The article requires that there be one court called the Supreme Court; Congress, at its discretion, can create lower courts, whose judgments and orders are reviewable by the Supreme Court. Article Three also creates the right to trial by jury in all criminal cases, defines the crime of treason, and charges Congress with providing for a punishment for it. This Article also sets the kinds of cases that may be heard by the federal judiciary, which cases the Supreme Court may hear first (called original jurisdiction), and that all other cases heard by the Supreme Court are by appeal under such regulations as the Congress shall make.

Federal relationships

The States

Main article: Article Four of the United States ConstitutionArticle Four outlines the relation between the states and the relation between the federal government. In addition, it provides for such matters as admitting new states as well as border changes between the states. For instance, it requires states to give "full faith and credit" to the public acts, records, and court proceedings of the other states. Congress is permitted to regulate the manner in which proof of such acts, records, or proceedings may be admitted. The "privileges and immunities" clause prohibits state governments from discriminating against citizens of other states in favor of resident citizens (e.g., having tougher penalties for residents of Ohio convicted of crimes within Michigan).

United States of America

This article is part of the series:

United States ConstitutionOriginal text of the Constitution Preamble

Articles of the Constitution

I · II · III · IV · V · VI · VIIAmendments to the Constitution Bill of Rights

I · II · III · IV · V

VI · VII · VIII · IX · X

Subsequent Amendments

XI · XII · XIII · XIV · XV

XVI · XVII · XVIII · XIX · XX

XXI · XXII · XXIII · XXIV · XXV

XXVI · XXVII

Unratified Amendments

I(1) · XIII(1) · XIII(2) · XX(1) · XXVII(1) · XXVII(2)

It also establishes extradition between the states, as well as laying down a legal basis for freedom of movement and travel amongst the states. Today, this provision is sometimes taken for granted, especially by citizens who live near state borders; but in the days of the Articles of Confederation, crossing state lines was often a much more arduous and costly process. Article Four also provides for the creation and admission of new states. The Territorial Clause gives Congress the power to make rules for disposing of federal property and governing non-state territories of the United States. Finally, the fourth section of Article Four requires the United States to guarantee to each state a republican form of government, and to protect the states from invasion and violence.

Amendments

Main article: Article Five of the United States ConstitutionAn amendment may be ratified in three ways:

- The new amendment may be approved by two-thirds of both houses of Congress, then sent to the states for approval.

- Two-thirds of the state legislatures may apply to Congress for a constitutional convention to consider amendments, which are then sent to the states for approval.

- Congress may require ratification by special convention. The convention method has been used only once, to approve the 21st Amendment (repealing prohibition, 1933).

Regardless of the method of proposing an amendment, final ratification requires approval by three-fourths of the states.

Today Article Five places only one limit on the amending power: no amendment may deprive a state of equal representation in the Senate without that state's consent. The original Article V included other limits on the amending power regarding slavery and taxation; however, these limits expired in 1808.

Central government

Main article: Article Six of the United States ConstitutionArticle Six establishes the Constitution, and the laws and treaties of the United States made according to it, to be the supreme law of the land, and that "the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, any thing in the laws or constitutions of any state notwithstanding." It also validates national debt created under the Articles of Confederation and requires that all federal and state legislators, officers, and judges take oaths or affirmations to support the Constitution. This means that the states' constitutions and laws should not conflict with the laws of the federal constitution and that in case of a conflict, state judges are legally bound to honor the federal laws and constitution over those of any state.

Article Six also states "no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States."

Ratification

Main article: Article Seven of the United States ConstitutionArticle Seven sets forth the requirements for ratification of the Constitution. The Constitution would not take effect until at least nine states had ratified the Constitution in state conventions specially convened for that purpose, and it would only apply to those states that ratified it.[18] (See above Drafting and ratification requirements.)

Amendments

Amendment of the state Constitutions at the time of the 1787 Constitutional Convention required only a majority vote in a sitting legislature of a state, as duly elected representatives of its sovereign people. The next session of a regularly elected assembly could do the same. This was not the “fundamental law” the founders such as James Madison had in mind.

Nor did they want to perpetuate the paralysis of the Articles by requiring unanimous state approval. The Articles of Confederation had proven unworkable within ten years of its employment. Between the options for changing the “supreme law of the land”, too easy by the states, and too hard by the Articles, the Constitution offered a federal balance of the national legislature and the states.

Procedure

Three steps to

Amendments-

House-passed 12 proposals

2/3-majority, then to Senate

(States later ratify 10 of 12) -

Senate-passed 12 proposals

2/3-majority, then 3/4 States =

Bill of Rights

Changing the “fundamental law” is a two-part process of three steps: amendments are proposed then they must be ratified by the states. An Amendment can be proposed one of two ways. Both ways have two steps. It can be proposed by Congress, and ratified by the states. Or on demand of two-thirds of the state legislatures, Congress could call a constitutional convention to propose an amendment, then to be ratified by the states.