- History of Michigan

-

See also Timeline of Michigan history.

Main article: Michigan Michigan in 1718, Guillaume de L'Isle map, approximate state area highlighted.

Michigan in 1718, Guillaume de L'Isle map, approximate state area highlighted.

Thousands of years before the arrival of the first Europeans, eight indigenous tribes lived in what is today the state of Michigan. They included the Ojibwa, Menominee, Chippawa, Miami, Ottawa, and Potawatomi, who were part of the Algonquian family of Amerindians, as well as the Wyandot, who were from the Iroquoian family and lived in the area of present-day Detroit. It is estimated that the native population at the time the first European arrived was 15,000.

The first white explorer to visit Michigan was the Frenchman Étienne Brûlé in 1620, who began his expedition from Quebec City on the orders of Samuel de Champlain and traveled as far as the Upper Peninsula. Afterward, the area became part of Louisiana, one of the large colonial provinces of New France. The first permanent European settlement in Michigan was founded in 1668 at Sault Ste. Marie by Jacques Marquette, a French missionary.

The French built several trading posts, forts, and villages in Michigan during the late 17th century. Among them, the most important was Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit, established by Antoine de Lamothe Cadillac. This grew to become Detroit. Up until this time, French activities in the region were limited to hunting, trapping, trading with and the conversion of local Indians, and some limited subsistence agriculture. By 1760, the Michigan countryside had only a few hundred white inhabitants.

Territorial disputes between French and British colonists helped start the French and Indian War as part of the larger Seven Years' War, which took place from 1754 to 1763 and resulted in the defeat of France. As part of the Treaty of Paris, the French ceded all of their North American colonies east of the Mississippi River to Britain. Thus the future Michigan was handed over to the British. In 1774, the area was made part of Quebec. It continued to be sparsely populated. Regional growth proceeded slowly because the British were more interested in the fur trade and peace with the natives than in settlement of the area.

Contents

From 1776 to 1837

Unfinished contemporaneous painting of the American diplomatic negotiators of the Treaty of Paris which brought official conclusion to the Revolutionary War and gave possession of Michigan and other territory to the new United States.

Unfinished contemporaneous painting of the American diplomatic negotiators of the Treaty of Paris which brought official conclusion to the Revolutionary War and gave possession of Michigan and other territory to the new United States.

During the American Revolutionary War, the local European population, who were primarily American colonists that supported independence, rebelled against Britain. The British, with the help of local tribes, continually attacked American settlements in the region starting in 1776 and conquered Detroit. In 1781, Spanish raiders led by a French Captain Eugene Poure travelled by river and overland from St Louis, liberated British-held Fort St Joseph, and handed authority over the settlement to the Americans the following day. The war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, and Michigan passed into the control of the newly formed United States of America. In 1787, the region became part of the Northwest Territory. The British, however, continued to occupy Detroit and other fortifications and did not definitively leave the area until after the implementation of the Jay Treaty in 1796.

The land which is now Michigan was made part of Indiana Territory in 1800. Most was declared as Michigan Territory in 1805, including all of the Lower Peninsula. During the War of 1812, British forces from Canada captured Detroit and Fort Mackinac early on, giving them a strategic advantage and encouraging native revolt against the United States. American troops retook Detroit in 1813 and Fort Mackinac was returned to the Americans at the end of the war in 1815.

Over the 1810s, the indigenous Ojibwa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi tribes increasingly decided to oppose white settlement and sided with the British against the U.S. government.

After their defeat in the War of 1812, the tribes were forced to sell all of their land claims to the U.S. federal government by the Treaty of Saginaw and the Treaty of Chicago. After the war, the government built forts in some of the northwest territory, such as at Sault Ste. Marie. In the 1820s, the U.S. government assigned Indian agents to work with the tribes, including arranging land cessions and relocation. They forced most of the Native Americans to relocate from Michigan to Indian reservations further west.

During the 1820s, the population of Michigan Territory grew rapidly, largely because of the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825. Its connection of the navigable waters of the middle Great Lakes to those of the Atlantic Ocean dramatically sped up transportation between the eastern states and the less-inhabited western territories. The canal created new possibilities for transport of produce and goods to market, as well as eased passage of migrants to the west.

Michigan's oldest university, the University of Michigan was founded in Detroit in 1817 and was later moved to its present location in Ann Arbor. The state's oldest cultural instititon, the Historical Society of Michigan, was established by territorial governor Lewis Cass and explorer Henry Schoolcraft in 1828.

Rising settlement prompted the elevation of Michigan Territory to that of the present-day state. In 1835, the federal government enacted a law that would have created a State of Michigan. A territorial dispute with Ohio over the Toledo Strip, a stretch of land including the city of Toledo, delayed the final accession of statehood. The disputed zone became part of Ohio by the order of a revised bill passed by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by President Andrew Jackson which also gave compensation to Michigan in the form of control of the Upper Peninsula. On January 26, 1837, Michigan became the 26th state of the Union.

From 1837 to 1900

During the early 1840s, large deposits of copper and iron ores were discovered on the Upper Peninsula.

Michigan actively participated in the American Civil War sending thousands of volunteers.[1] After the war, the local economy became more varied and began to prosper. During the 1870s, the lumber industry, dairy farming and diversified industry grew rapidly in the state. The population doubled between 1870 and 1890.

Toward the end of the millenium , the state government established a state school system on the German model, with public schools, high schools, normal schools or colleges for training teachers of lower grades, and colleges for classical academic studies and professors. It dedicated more funds to public education than did any other state in the nation. Within a few years, it established four-year curriculums at its normal colleges, and was the first state to establish a full college program for them.

Railroads have been vital in the history of the population and trade of rough and finished goods in the state of Michigan. While some coastal settlements had previously existed, the population, commercial, and industrial growth of the state further bloomed with the establishment of the railroad.

1900 to 1941

Urban Michigan grew rapidly in the early 20th century, pulled along by the automobile industry in Detroit and vicinity, as well as the breakfast cereal industry in Battle Creek, and machine shops in medium and small cities across the state.

Automobiles

During the early 20th century, manufacturing industries became the main source of revenue for Michigan – in large part, because of the automobile. In 1899, the Olds Motor Vehicle Company opened a factory in Detroit. In 1903, Ford Motor Company was also founded there. With the mass production of the Ford Model T, Detroit became the world capital of the auto industry. General Motors is based in Detroit, Chrysler is located in Auburn Hills, and Ford is headquartered in nearby Dearborn. Both corporations constructed large industrial complexes in the Detroit metropolitan area, exemplified by the River Rouge Plant, which have made Michigan a national leader in manufacturing since the 1910s. This industrial base produced greatly during World War I, filling a huge demand for military vehicles.

Jackson was home to one of the first car industry developments. Even before Detroit began building cars on assembly lines, Jackson was busy making parts for cars and putting them together in 1901. By 1910, the auto industry became Jackson's main industry. Over twenty different cars were once made in Jackson. Including: Reeves, Jaxon, Jackson, CarterCar, Orlo, Whiting, Butcher and Gage, Buick, Janney, Globe, Steel Swallow, C.V.I., Imperial, Ames-Dean, Cutting, Standard Electric, Duck, Briscoe, Argo, Hollier, Hackett, Marion-Handly, Gem, Earl, Wolverine, and Kaiser-Darrin. Today the auto industry remains one of the largest employers of skilled machine operators in Jackson County.

Immigrants

With the expansion of industry, hundreds of thousands of migrants from the South and immigrants from eastern and southern Europe were attracted to Detroit. In a short time, it became the fourth largest city in the country - housing shortages persisted for years even as new housing was developed throughout the city. Ethnic immigrant enclaves rapidly developed where churches, bakeries and businesses supported unique communities. A guide to the city written in the 1930s noted that there were students speaking more than 35 languages in the public schools. Ethnic festivals were a regular part of the city's culture. At the same time, such rapid social change created an environment in which the second Ku Klux Klan recruited members in the city. Their influence was at a peak in 1925, but membership fell quickly after that.

Progressivism

The cities of Michigan were centers of municipal reform during the Progressive Era. Using Kalamazoo as her base, Caroline Bartlett Crane (1858–1935) became a nationally famous expert on municipal sanitation. She was nonpolitical, but scientific in her methods, and energetic in her approach. She made 60 surveys and studies in 14 states that dealt with housing conditions in tenements, of schools, jails, water and sewer systems. She identified and found solutions for air pollution. Crane had a sharp eye for inefficiency, waste, and mismanagement, and was always ready to point out improvements and explain what the best practices were in the nation.[2]

A representative politician was George E. Ellis, mayor of Grand Rapids (1906–16). He is remembered as the most dynamic and innovative mayor in the city's history, as well as a powerful political boss who built a coalition of working-class ethnic voters, combined with middle-class reform elements. He broadened the base of political participation, and was on the left or liberal side of the political spectrum.[3] Somewhat more conservative, much better known, was Mayor Hazen Pingree of Detroit (1889–1896), who bought progressivism to the governor's mansion with his election in 1896. Pingree was elected mayor in 1889 by promising to expose and end corruption in city paving contracts, sewer contracts, and the school board. He fought privately owned utility monopolies, And set up Competing companies owned by the city. He fought Tom L. Johnson, president of the Detroit City Railways, over lowering streetcar fares to three-cents. When the depression of 1893 caused large-scale unemployment, Pingree expanded welfare programs, initiated public works for the unemployed, built new schools, parks, and public baths, And set aside plots of vacant city land for workers to plant their own vegetable gardens. As the Republican governor, he promoted Higher railroad taxes to pay for his reforms.[4]

Women

Most young women took jobs before marriage, then quit. Before the growth of high schools after 1900, most women left school after the 8th grade at about age 15. Ciani (2005) shows that type of work they did reflected their ethnicity and and marital status. African American mothers often chose day labor, usually as domestic servants, because of the flexibility it afforded. Most mothers receiving pensions were white and sought work only when necessary.[5]

Across the state middle class homemakers shaped numerous new and expanded charitable and professional associations, and promoted mothers' pensions, and expanded forms of social welfare. Many of the Protestant homemakers were active in the temperance and suffrage movements as well. The Detroit Federation of Women's Clubs (DFWC) promoted a very wide range of activities for civic minded middle-class women who conformed to traditional gender roles. The Federation argued that safety and health issues were of greatest concern to mothers and could only be solved by improving municipal conditions outside the home. The Federation pressured Detroit officials to upgrade schools, water supplies and sanitation facilities, and to require safe food handling, and traffic safety. However, the membership was divided on going beyond these issues or collaborating with ethnic or groups or labor unions; it refused to stretch traditional gender boundaries, giving it a conservative reputation.[6]

Depression

The Great Depression caused severe economic hardship in Michigan. Thousands of auto industry workers were dismissed along with other workers from several sectors of the state economy. The financial suffering was aggravated by the fact that remaining copper reserves in the state lay deep underground. With the discovery of copper finds in other states located in less deep rock layers, local mining fell sharply and most miners left the region or resigned themselves to short hours and long unemployment. The New Deal of Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt spent heavily on relief, recovery, and reform, and effected a political revolution that gave the Democratic Coalition Parity with the Republican Party. Young men from relief families signed up for six month tours in one of the state's 50 Civilian Conservation Corps camps in rural areas. They were paid five dollars a month, plus room, board, clothing and medical care, while their families received $25 a month. The Works Progress Administration was the largest federal agency. It hired more than 500,000 unemployed people (80% men) in Michigan alone to construct major public works such as roads, public buildings, and sewer systems.

Unions

Union members occupying a General Motors body factory during the Flint Sit-Down Strike of 1937 which spurred the organization of militant CIO unions in auto industry

Union members occupying a General Motors body factory during the Flint Sit-Down Strike of 1937 which spurred the organization of militant CIO unions in auto industry

Thanks to new federal laws, labor unions grew rapidly after 1935, and for the first time became a major presence in large factories. The Flint Sit-Down Strike of 1936-37 was the decisive event in the formation of the United Auto Workers Union (UAW). During World War II Walter Reuther took control of the UAW, and soon led major strikes in 1946. He ousted the Communists from the positions of power, especially at the Ford local. He was one of the most articulate and energetic leaders of the CIO, and of the merged AFL-CIO. Using brilliant negotiating tactics he leveraged high profits for the Big Three automakers into higher wages and superior benefits for UAW members.

After 1941

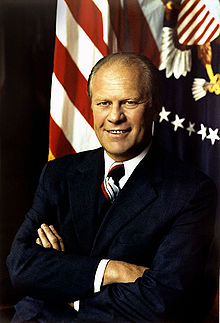

Gerald Ford, a politician from Grand Rapids who was elected to the House of Representatives thirteen times and also served as House Minority Leader and then Vice President, became the 38th President of the United States after the resignation of Richard Nixon.

Gerald Ford, a politician from Grand Rapids who was elected to the House of Representatives thirteen times and also served as House Minority Leader and then Vice President, became the 38th President of the United States after the resignation of Richard Nixon.

The entry of the United States into World War II the same year ended the economic contraction in Michigan. Wartime required the large-scale production of weapons and military vehicles, leading to a massive number of new jobs being filled. After the end of the war, both the automotive and copper mining industries recovered.

Starting during WWI, the Great Migration fueled the movement of thousands of African-Americans from the South to industrial jobs in Michigan and, especially, Detroit. Migration of white southerners to the city increased the volatility of change. Population increases continued with industrial expansion during WWII and afterward. African Americans contributed to a new vibrant urban culture, with expansion of new music, food and culture.

The postwar years were initially a prosperous time for industrial workers, who achieved middle-class livelihoods. These were the years of the creation and popularity of Motown Records. By late mid-century, however, deindustrialization and restructuring cost many jobs. The economy suffered and the city postponed needed changes. Neglect of social problems and urban decline fed racial conflicts. In 1967 the 12th St. Riot erupted, lasting eight days, causing 25 million dollars in damages, and resulting in 43 deaths. The violence caused many people to leave the city who could, to avoid future problems.

The 1973 Oil Crisis caused economic recession in the United States and greatly affected the Michigan economy. Afterward, automobile companies in the United States faced greater multinational competition, especially from Japan. As a consequence, domestic auto makers enacted cost-cutting measures to remain competitive at home and abroad. Unemployment rates rose dramatically in the state.

Throughout the 1970s, Michigan possessed the highest unemployment rate of any U.S. state. Large spending cuts to education and public health were repeatedly made in an attempt to reduce growing state budget deficits. A strengthening of the auto industry and an increase in tax revenue stabilized government and household finances in the 1980s. Increasing competition by Japanese and South Korean auto companies continues to challenge the state economy, which depends heavily on the automobile industry. Since the late 1980s, the government of Michigan has actively sought to attract new industries, thus reducing economic reliance on a single sector.

Further reading

- Bald, F. Clever, Michigan in Four Centuries (1961)/

- Browne, William P. and - Kenneth VerBurg. Michigan Politics & Government: Facing Change in a Complex State University of Nebraska Press. 1995.

- Bureau of Business Research, Wayne State U. Michigan Statistical Abstract (1987).

- Clarke Historical Library, Central Michigan University, Bibliographies for Michigan by region, counties, etc..

- Dunbar, Willis F. and George S. May. Michigan: A History of the Wolverine State, 3rd ed. (1995)

- Michigan, State of. Michigan Manual (annual), elaborate detail on state government.

- Michigan Historical Review Central Michigan University (quarterly).

- Nolan, Alan T. The Iron Brigade: A Military History (1994), famous Civil War combat unit

- Press, Charles et al., Michigan Political Atlas (1984).

- Public Sector Consultants. Michigan in Brief. An Issues Handbook (annual)

- Rich, Wilbur. Coleman Young and Detroit Politics: From Social Activist to Power Broker (Wayne State University Press, 1988).

- Rubenstein, Bruce A. and Lawrence E. Ziewacz. Michigan: A History of the Great Lakes State. (2002)

- Sisson, Richard, Ed. The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia (2006)

- Trap. Paul, and Larry Wagenaar. Michigan History Directory of Historical Societies, Museums, Archives, Historic Sites, Agencies and Commissions (12th Ed. 2008)

- Weeks, George, Stewards of the State: The Governors of Michigan (Historical Society of Michigan, 1987).

See also

Main article: Historical outline of Michigan- Algonquian peoples

- European colonization of the Americas

- History of Detroit

- History of Ford Motor Company

- History of General Motors

- History of railroads in Michigan

- History of the Midwestern United States

- International Boundary Waters Treaty

- Inland Northern American English

- Northwest Ordinance

- List of Michigan county name etymologies

- List of museums in Michigan

- Sixty Years' War

- Timeline of Michigan history

- Timeline of the Toledo Strip/War

- War of 1812

Notes

- ^ Robert E., Mitchell, “Civil War Recruiting and Recruits from Ever-Changing Labor Pools: Midland County, Michigan, as a Case Study,” Michigan Historical Review, 35 (Spring 2009), 29–60.

- ^ Alan S. Brown, "Caroline Bartlett Crane and Urban Reform," Michigan History, July 1972, Vol. 56 Issue 4, pp 287-301

- ^ Anthony R. Travis, "Mayor George Ellis: Grand Rapids Political Boss And Progressive Reformer," Michigan History, March 1974, Vol. 58 Issue 2, pp 101-130

- ^ Melvin G. Holli, Reform in Detroit: Hazen S. Pingree and Urban Politics (Oxford U.P., (1969)

- ^ Kyle E. Ciani, "Hidden Laborers: Female Day Workers In Detroit, 1870-1920," Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, Jan 2005, Vol. 4 Issue 1, pp 23-51

- ^ Jayne Morris-Crowther, "Municipal Housekeeping: The Political Activities of the Detroit Federation of Women's Clubs in the 1920s," Michigan Historical Review, March 2004, Vol. 30 Issue 1, pp 31-57

External links

History of Michigan Timeline Glaciation · Paleo-Indian · Archaic · Woodland · Algonquian · French · British · Territory · State

Native Council of Three Fires · Fox · Kickapoo · Mascouten · Menominee · Miami · Ojibwe (Chippewa) · Odawa (Ottawa) · Potawatomi · Sac (Sauk)

Colonial Fur Trade · Coureurs des Bois · Voyageurs · Iroquois Wars · New France · Detroit · Fox Wars · Fort Michilimackinac · Seven Years' War · Peace of Paris · Pontiac's Rebellion · Royal Proclamation · Indian Reserve · Quebec Act · Revolutionary War · Treaty of Paris

United States MilitaryJay Treaty · Treaty of Saginaw · Treaty of Chicago · Toledo War · Battle of Windsor · Treaty of Fond du Lac · Treaty of La Pointe ·

Civil WarIndustryPoliticsHistory of the United States by political division States - Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

Federal district Insular areas - American Samoa

- Guam

- Northern Mariana Islands

- Puerto Rico

- U.S. Virgin Islands

Outlying islands - Bajo Nuevo Bank

- Baker Island

- Howland Island

- Jarvis Island

- Johnston Atoll

- Kingman Reef

- Midway Atoll

- Navassa Island

- Palmyra Atoll

- Serranilla Bank

- Wake Island

Categories:- History of Michigan

- History of the United States by state

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.