- Marx's theory of alienation

-

Part of a series on Marxism  Social sciencesAlienation · Bourgeoisie

Social sciencesAlienation · Bourgeoisie

Base and superstructure

Class consciousness

Commodity fetishism

Exploitation · Human nature

Ideology · Proletariat

Private property

Reification · Cultural hegemony

Relations of production

Scientific socialism

ImmiserationCapitalist mode of production

Socialist mode of production

Capital accumulation

Commodity (Marxism)

Marxian economics

Communism

Economic determinism

Labour power · Law of value

Means of production

Mode of production

Perspectives on Capitalism

Productive forces

Surplus labour · Surplus value

Transformation problem

Wage labour · Crisis theoryHistoryCategoriesAll categorised articlesCommunism portal

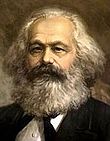

Marx's theory of alienation (Entfremdung in German, which literally means "estrangement"), as expressed in the writings of the young Karl Marx (in particular the Manuscripts of 1844), refers to the separation of things that naturally belong together, or to put antagonism between things that are properly in harmony. In the concept's most important use, it refers to the social alienation of people from aspects of their "human nature" (Gattungswesen, usually translated as 'species-essence' or 'species-being'). He believed that alienation is a systematic result of capitalism.

Marx's theory relies on Feuerbach's The Essence of Christianity (1841), which argues that the idea of God has alienated the characteristics of the human being. Stirner would take the analysis further in The Ego and Its Own (1844), declaring that even 'humanity' is an alienating ideal for the individual, to which Marx and Engels responded in The German Ideology (1845).

Contents

Types

In the labour process

According to Marx, alienation is a systemic result of capitalism. Marx's theory of alienation is founded upon his observation that, within the capitalist mode of production, workers invariably lose determination of their lives and destinies by being deprived of the right to conceive of themselves as the director of their actions, to determine the character of their actions, to define their relationship to other actors, and to use or own the value of what is produced by their actions. Workers become autonomous, self-realized human beings, but are directed and diverted into goals and activities dictated by the bourgeoisie, who own the means of production in order to extract from workers the maximal amount of surplus value possible within the current state of competition between industrialists. By working, each contributes to the common wealth. Alienation in capitalist societies occurs because the worker can only express this fundamentally social aspect of individuality through a production system that is not collectively, but privately owned; a privatized asset for which each individual functions not as a social being, but as an instrument:

Let us suppose that we had carried out production as human beings. Each of us would have in two ways affirmed himself and the other person. 1) In my production I would have objectified my individuality, its specific character, and therefore enjoyed not only an individual manifestation of my life during the activity, but also when looking at the object I would have the individual pleasure of knowing my personality to be objective, visible to the senses and hence a power beyond all doubt. 2) In your enjoyment or use of my product I would have the direct enjoyment both of being conscious of having satisfied a human need by my work, that is, of having objectified man’s essential nature, and of having thus created an object corresponding to the need of another man's essential nature. ... Our products would be so many mirrors in which we saw reflected our essential nature.—Comment on James MillIn the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 Marx identifies four types of alienation in labor under capitalism.[1][2] [Former reference incomplete, latter leads to dead link] These include:

- Alienation of the worker from the work he produces, from the product of his labor. The product's design and the manner in which it is produced are determined not by its actual producers, nor even by those who consume products, but rather by the Capitalist class, which appropriates labor - including that of designers and engineers - and seeks to shape consumers' taste in order to maximize profit. Aside from the lack of workers’ control over the design and production protocol, however, this form of alienation refers more broadly to the conversion of the activity of work, which is conducted to generate a use value in the form of a product, into a commodity itself which - like products - can be assigned an exchange value. In other words, the Capitalist gains control of the worker - including intellectual and creative workers - and the beneficial effects of his work by setting up a system that converts the worker's efforts not only into a useful, concrete thing capable of benefiting consumers, but also into an illusory, reified concept—something called "work"—which is compensated in the form of wages at a rate as low as possible to maintain a maximum rate of return on the industrialist's investment capital (an aspect of exploitation). Furthermore, within this illusory framework, the exchange value that could be generated by the sale of products and returned to workers in the form of profits is absconded with by the managerial and Capitalist classes.

- Alienation of the worker from working, from the act of producing itself. This kind of alienation refers to the patterning of work in the Capitalist Mode of Production into an endless sequence of discrete, repetitive, trivial, and meaningless motions, offering little, if any, intrinsic satisfaction. The worker's labor power is commodified into exchange value itself in the form of wages. A worker is thus estranged from the unmediated relation to his activity via such wages. Aside from the limitation of the inherent plurality of one's species being that the Capitalist division of labor imposes upon workers, Marx was also identifying another feature of exploitation with this kind of alienation. According to Marx, one's species being is fulfilled when it maintains control over the subject of its labor by the ability to determine how it shall be used directly or exchanged for something else. Capitalism removes the right of the worker to exercise control over the value or effects of his labor, robbing him of the ability to either consume the product he makes directly or receive the full value of the product when it is sold: this is the first alienation of worker from product. However, the first alienation contributes to the second alienation of worker from the very act of working, as it removes the worker's feeling of control over the use and exchange of his labor power. This loss of control disrupts the ability of the worker to specialize, focus, direct or apply the inherently plural potency of his species being, thus separating or alienating any activity that he does engage in from the intentional core of that being.

- Alienation of the worker from himself as a producer, from his or her "species being" or "essence as a species". To Marx, this human essence was not separate from activity or work, nor static, but includes the innate potential to develop as a human organism. Species being is a concept that Marx deploys to refer to what he sees as the original or intrinsic essence of the species, which is characterized both by plurality and dynamism: all beings possess the tendency and desire to engage in multiple activities to promote their mutual survival, comfort and sense of inter-connection. A man's value consists in his ability to conceive of the ends of his action as purposeful ideas distinct from any given step of realizing them: man is able to objectify his intentional efforts in an idea of himself (the subject) and an idea of the thing which he produces (the object). Animals, according to Marx, do not objectify themselves or their products as ideas because they engage in self-sustaining actions directly, without sustained future projection or conscious intention. While human nature or essence does not exist apart from specific, historically conditioned activity, it becomes actualized as man's species being when man - within his historical circumstances - is free to subordinate his will to the demands imposed by his own imagination and not those mandated solely for the purpose of allowing others to do so.

- Notwithstanding, the character of an individual's consciousness (his will and imagination) is conditioned by his relationship to that which facilitates survival; since any individual's survival and betterment is fundamentally dependent upon cooperation with others, a given person's personal consciousness is determined inter-subjectively or collectively rather than merely subjectively or individually. As far as has been heretofore observed, all societies have, according to Marx, organized groups with differing basic relationships to the means of material survival available to them—i.e. the means of production. One group has owned and controlled the means while another has operated them, the goal of the former being to benefit as much as possible through the latter's efforts. Every time there is a shift in the organization of the means of production—as with say, the displacement of agrarian feudalism and pre-industrial mercantilism with the technologies that gave rise to industrial capitalism—there is a rearrangement and rupture of the social class structure that relates to those means—a class structure Marx termed the relations of production. That is to say, a new class relationship emerges, subordinating one group and the species beings of its members to the activities and corresponding values that enable it to operate the means of production for the profit of the dominant group, whose consciousness and values are also conditioned to maintain this dominance.

- While industrialization holds the promise of the masses' eventual liberation from an imagination conditioned chiefly by brute necessity, the division of labor within Industrial Capitalism blunts the worker's "species being" and renders him as a replaceable cog in an abstract machine instead of a human being capable of defining his own value through direct, purposeful activity (see Marx's theory of human nature). And yet, industrialization, in Marx's view, would eventually progress to a state of near-total mechanization and automation of productive processes. During this progression, the newly dominant Bourgeoisie Capitalist class would exploit the Industrial working class or Proletariat to the degree that the value they excised from their labor would begin to infringe upon the ability of the Proletariat to materially survive. When this begins to occur, and when the productive forces are sufficiently developed, there will be a final revolution whose end result will be the reorientation of the relations of production to the means of production in a Communist mode of production. In the Communist mode of production, because all members of the society will relate to the means of production on a fundamentally equal and non-conflictual manner, there will be no fundamental differentiation between groups or classes as previously, and the species being of every individual will assume a full actualization of its tendencies, as the application of his efforts will return to him in direct, unmediated proportion to what he is able to conceive. This is partly due to the fact that a Communist society would distribute the benefits and duties of production evenly, in accordance with the capacities its members, such that each member could direct his action more directly towards his interests and preferences rather than a narrowly designated function designed to generate maximal return of value to an owner.

- In this classless, collectively managed society, the dialectical exchange of value between one worker's objectified labor power (via production) and another's benefit from that objectification (via consumption) will not be directed by the narrow interest of one group over the needs of another, and will thus directly enrich the consciousness and material state of all of producers and consumers to the maximal possible degree. Though production will still be differentiated to some degree, it will be directed by the collective demand and not the narrow demand of one class at the expense of those of another. Since ownership will be shared, the relation of individuals' consciousness to the mode of production will be identical, and will assume the character that corresponds, as in previous times, to the interest of its group: the universal, Communist class. The direct, un-siphoned return of the fruit of each worker's labor to that group's interest - and thus as directly as possible to his own interest, which assumes the character of his group's - will constitute an un-alienated state of labor, restoring the worker to the fullest exercise and determination of his species being as is possible at any given moment in the future development of Communist society.

- Alienation of the worker from other workers or producers. Capitalism reduces labour to a commercial commodity to be traded on the market, rather than a social relationship between people involved in a common effort for survival or betterment. The competitive labour market is set up in Industrial Capitalist economies to extract as much value as possible in the form of capital from those who work to those who own enterprises and other assets that control the means of production. This causes the relations of production to become conflictual; i.e. it pits worker against worker, alienating members of the same class from their mutual interest, an effect Marx called false consciousness.

Marx also placed emphasis on the role of religion in the alienation process, independently from his famous quotation on the "opiate of the masses".[3]

Significance in Marx's thought

"For Hegel, the unhappy consciousness is divided against itself, separated from its ‘essence’, which it has placed in a ‘beyond’. Marx used essentially the same notion to portray the situation of modern individuals—especially modern wage labourers—who are deprived of a fulfilling mode of life because their life-activity as socially productive agents is devoid of any sense of communal action or satisfaction and gives them no ownership over their own lives or their products. In modern society, individuals are alienated in so far as their common human essence, the actual co-operative activity which naturally unites them, is power-less in their lives, which are subject to an inhuman power—created by them, but separating and dominating them instead of being subject to their united will. This is the power of the market, which is ‘free’ only in the sense that it is beyond the control of its human creators, enslaving them by separating them from one another, from their activity, and from its products. The German verbs entäussern and entfremden are reflexive, and in both Hegel and Marx alienation is always fundamentally self-alienation. Fundamentally, to be alienated is to be separated from one's own essence or nature; it is to be forced to lead a life in which that nature has no opportunity to be fulfilled or actualized. In this way, the experience of ‘alienation’ involves a sense of a lack of self-worth and an absence of meaning in one's life." [4]Influence from Hegel and Feuerbach

Alienation is a foundational claim in Marxist theory. Hegel described a succession of historic stages in the human Geist (Spirit), by which that Spirit progresses towards perfect self-understanding, and away from ignorance. In Marx's reaction to Hegel, these two, idealist poles are replaced with materialist categories: spiritual ignorance becomes alienation, and the transcendent end of history becomes man's realisation of his species-being; triumph over alienation and establishment of an objectively better society.

This teleological (goal-oriented) reading of Marx, particularly supported by Alexandre Kojève before World War II, is criticized by Louis Althusser in his writings about "random materialism" (matérialisme aléatoire). Althusser claimed that said reading made the proletariat the subject of history (i.e. Georg Lukács' History and Class Consciousness [1923] published at the Hungarian Soviet Republic's fall), was tainted with Hegelian idealism, the "philosophy of the subject" that had been in force for five centuries, which was criticized as the "bourgeois ideology of philosophy".

Relation to Marx's theory of history

In The German Ideology Marx writes that 'things have now come to such a pass that the individuals must appropriate the existing totality of productive forces, not only to achieve self-activity, but, also, merely to safeguard their very existence'.[5] In other words, Marx seems to think that, while humans do have a need for self-activity (self-actualisation, the opposite of alienation), this will be of secondary historical relevance. This is because he thinks that capitalism will increase the economic impoverishment of the proletariat so rapidly that they will be forced to make the social revolution just to stay alive - they probably wouldn't even get to the point of worrying that much about self-activity. This doesn't mean, though, that tendencies against alienation only manifest themselves once other needs are amply met, only that they are of reduced importance. The work of Raya Dunayevskaya and others in the tradition of Marxist humanism drew attention to manifestations of the desire for self-activity even among workers struggling for more basic goals.

Class

In this passage, from The Holy Family, Marx says that capitalists and proletarians are equally alienated, but experience their alienation in different ways:

The propertied class and the class of the proletariat present the same human self-estrangement. But the former class feels at ease and strengthened in this self-estrangement, it recognizes estrangement as its own power and has in it the semblance of a human existence. The class of the proletariat feels annihilated, this means that they cease to exist in estrangement; it sees in it its own powerlessness and the reality of an inhuman existence. It is, to use an expression of Hegel, in its abasement the indignation at that abasement, an indignation to which it is necessarily driven by the contradiction between its human nature and its condition of life, which is the outright, resolute and comprehensive negation of that nature. Within this antithesis the private property-owner is therefore the conservative side, the proletarian the destructive side. From the former arises the action of preserving the antithesis, from the latter the action of annihilating it.[6]

Further reading

"I am not interested in dry economic socialism. We are fighting against misery, but we are also fighting against alienation. One of the fundamental objectives of Marxism is to remove interest, the factor of individual interest, and gain, from people’s psychological motivations. Marx was preoccupied both with economic factors and with their repercussions on the spirit. If communism isn’t interested in this too, it may be a method of distributing goods, but it will never be a revolutionary way of life."Secondary literature

Marx's work can sometimes be daunting - many people[who?] would recommend reading a short introduction (such as one of those indicated below) to the concept first:

- Introductory article on alienation - from the Encyclopaedia of the Marxists Internet Archive.

- Short article on alienation - drawing mainly on the earlier works (from Lewis A. Coser, Masters of Sociological Thought: Ideas in Historical and Social Context, 2nd Ed., Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1977: 50-53.)

- Paul Blackledge (2008) Marxism and Ethics from International Socialism

- G.A. Cohen (1977) discusses alienation and fetishism in Ch. V of Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence.

- Althusser, For Marx, Verso

- Marcuse, Herbert, Reason & Revolution, Beacon

- Part I: Alienation of Karl Marx by Allen W. Wood in the Arguments of the Philosophers series provides a good introduction to this concept.

- Why Read Marx Today? by Jonathan Wolff provides a simple introduction to the concept. It is especially clear differentiating the various types of alienation which Marx discusses.

- Marx and human nature: refutation of a legend by Norman Geras, a brief book, contains much of relevance to alienation by studying the closely related concept of human nature.

- Alienation: Marx's conception of man in capitalist society by Bertell Ollman. Selected chapters can be read online [2].

- Alienation and Techne in the Thought of Karl Marx, by Kostas Axelos

- Shlomo Avineri, Hegel's Philosophy of Right and Hegel's Theory of the Modern State

- Lukács' The Young Hegel and Origins of the Concept of Alienation by István Mészáros

- Marx's Theory of Alienation by István Mészáros

- Ludwig Feuerbach at www.marxists.org

- The Evolution of Alienation: Trauma, Promise, and the Millennium, edited by Lauren Langman and Devorah K. Fishman. Lanham, 2006.

- "Does Alienation Have a Future? Recapturing the Core of Critical Theory," by Harry Dahms (in Langman and Fishman, The Evolution of Alienation, 2006).

- Alienation in American Society by Fritz Pappenheim, Monthly Review Volume 52, Number 2

- Karl Marx's Philosophy of Man (1975) by John Plamenatz

- Alienation (1970) by Richard Schacht

- Making Sense of Marx (1994) by Jon Elster

See also

- Commodity fetishism

- Ludwig Feuerbach's The Essence of Christianity (1841)

- Georg Lukács' theory of class consciousness and reification

- Character mask

References

- ^ A Dictionary of Sociology, Article: Alienation

- ^ See the notes of Max Stier, Intellectual Heritage lecturer and Temple University, on Marx's concept of alienation: [1]. Accessed 2 October 2010.

- ^ Marx on Alienation

- ^ Alienation: Faute De Mieux, Entäusserung, Entfremdung, Entäussern, Entfremden, Self, The Idea of a Critical Theory

- ^ Marx, Karl (Fall 1845 to mid-1846). "Part I: Feuerbach.Opposition of the Materialist and Idealist Outlook". The German Ideology. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/german-ideology/ch01d.htm.

- ^ Chapter 4 of The Holy Family- see under Critical Comment No. 2

- ^ The Many Faces of Socialism: Comparative Sociology and Politics, 1983, by Paul Hollander, Transaction Pub, ISBN 0-88738-740-3, Pg. 224

External links

Categories:- Marxist theory

- Philosophical concepts

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.