- Overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii

-

Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom Part of the Hawaiian Revolutions

The USS Boston's landing force on duty at the Arlington Hotel, Honolulu, at the time of the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy, January 1893. Lieutenant Lucien Young, USN, commanded the detachment, and is presumably the officer at right.[1]Date January 17, 1893 Location Honolulu, Hawaii Result Annexationist Victory - Hawaiian Surrender.

- Provisional Government established.

- Queen Lili'uokalani relinquishes power.

Belligerents Hawaiian League

United States

United States Kingdom of Hawaii

Kingdom of HawaiiCommanders and leaders Lorrin A. Thurston

John L. Stevens Liliʻuokalani

Liliʻuokalani

Samuel Nowlein

Samuel Nowlein

Charles B. Wilson

Charles B. WilsonStrength Honolulu Rifles

1,500 Militiamen

United States

1 cruiser, USS Boston496 troops[2] (several) Volunteers

85–110 Police

322–337 Royal Guard- 50–65 at Palace

- 272 at Barracks[3]

- 8–14 artillery pieces

- 1 Gatling gun

Casualties and losses None 1 wounded Hawaiian Revolutions- Bloodless Revolution

- Dominis

- Wilcox Rebellion

- Sandbag

- Overthrow

- Leper War

- Black Week

- Counter-Revolution

Until the 1890s the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was an independent sovereign state, recognized by the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Japan, and Germany. Though there were threats to Hawaii's sovereignty throughout the Kingdom's history, it was not until the signing, under duress, of the Bayonet Constitution in 1887, that this threat began to be realized. On January 17, 1893, the last monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, Queen Lili'uokalani, was deposed in a coup d'état led largely by American citizens who were opposed to Lili'uokalani's attempt to establish a new Constitution. The success of the coup efforts was supported by the landing of U.S. Marines, who came ashore at the request of the conspirators. The coup left the queen imprisoned at Iolani Palace under house arrest. The sovereignty of the Kingdom of Hawaii was lost to a Provisional Government led by the conspirators, later briefly becoming the Republic of Hawaii, before eventual annexation to the United States in 1898. One hundred years later, the U.S. Congress passed Public Law 103-150, otherwise known as the Apology Resolution,[4] signed by President Bill Clinton on November 23, 1993. The resolution[5] apologized for the U.S. Government's role in supporting the 1893 overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii.

The coup d'état that overthrew Queen Lili'uokalani was led by Lorrin A. Thurston, a grandson of American missionaries who derived his support primarily from the American and European business class residing in Hawaii and other supporters of the Reform Party of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Most of the leaders of the Committee of Safety which deposed the queen were American and European citizens who were also Kingdom subjects. They included legislators, government officers, and even a Supreme Court Justice of the Hawaiian Kingdom.[6]

The coup itself was relatively bloodless, with only one policeman wounded. Due to the Queen's desire "to avoid any collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life" for her subjects and after some deliberation, at the urging of advisers and friends, the Queen ordered her forces to surrender. Immediate annexation was prevented by the eloquent speech given by President Grover Cleveland to Congress at this time, in which he stated that:

"the military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war; unless made either with the consent of the government of Hawai`i or for the bona fide purpose of protecting the imperiled lives and property of citizens of the United States. But there is no pretense of any such consent on the part of the government of the queen ... the existing government, instead of requesting the presence of an armed force, protested against it. There is as little basis for the pretense that forces were landed for the security of American life and property. If so, they would have been stationed in the vicinity of such property and so as to protect it, instead of at a distance and so as to command the Hawaiian Government Building and palace. ... When these armed men were landed, the city of Honolulu was in its customary orderly and peaceful condition. ... "[7]

The Republic of Hawaii was nonetheless declared in 1894 by the same parties which had established the Provisional Government after the coerced signing of the Bayonet Constitution of 1887. Among them were Lorrin A. Thurston, a drafter of the Bayonet Constitution, and Sanford Dole who appointed himself President of the forcibly instated Republic on July 4, 1894.

The Bayonet Constitution allowed the monarch to appoint cabinet ministers, but had stripped him of the power to dismiss them without approval from the Legislature. Eligibility to vote was also altered, stipulating property value, defined in non-traditional terms, as a condition of voting eligibility. One result of this was the disenfranchisement of poor native Hawaiians and other ethnic groups who had previously had the right to vote. This guaranteed a voting monopoly by the landed aristocracy. Asians who comprised a large proportion of the population, were stripped of their voting rights as many Japanese and Chinese members of the population who had previously become naturalized as subjects of the Kingdom, subsequently lost all voting rights. Many Americans and wealthy Europeans, in contrast, acquired full voting rights at this time, without the need for Hawaiian citizenship.

Contents

Liliʻuokalani's constitution

Main article: 1893 Constitution of the Kingdom of HawaiiIn 1891, Kalākaua died and his sister Liliʻuokalani assumed the throne in the middle of an economic crisis. The McKinley Act had crippled the Hawaiian sugar industry by reducing duties on imports from other countries, eliminating the previous Hawaiian advantage due to the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875. Many Hawaii businesses and citizens were feeling pressure from the loss of revenue. Liliʻuokalani proposed a lottery system to raise money for her government. Also proposed was a controversial opium licensing bill. Her ministers, and even her closest friends, were opposed to this plan and unsuccessfully tried to dissuade her from pursuing these initiatives, both of which came to be used against her in the brewing constitutional crisis that was also underway.

Liliʻuokalani's chief desire was to restore power to the monarch by abrogating the 1887 "Bayonet" Constitution and promulgating a new one, an idea that seems to have been broadly supported by the Hawaiian population.[8] The 1893 Constitution would have both widened suffrage by reducing some wealth requirements, but also would have eliminated the voting privileges of European and American residents, thus disenfranchising many resident European and American businessmen. The queen toured several of the islands on horseback, talking to the people about her ideas and receiving overwhelming support, including a lengthy petition in support of a new constitution. When the Queen informed her cabinet of her plans, they withheld their support due to their clear understanding of the response this was likely to provoke.[9]

Besides the threatened loss of suffrage for European and American citizens of Hawaii, business interests within the Kingdom were concerned about the removal of foreign tariffs in the American sugar trade due to the McKinley Act (which effectively eliminated the favored status of Hawaiian sugar due to the Reciprocity Treaty), and considered the possibility of annexation to the United States (and enjoying the same sugar bounties as domestic producers) as a welcome side effect of ending the monarchy. A small but powerful group, led by Lorrin Thurston, had been set on the goal of annexation to the United States for years before the actual revolution.

Overthrow

The precipitating event[10] leading to the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii on January 17, 1893 was the attempt by Queen Liliuokalani to promulgate a new constitution which would have strengthened the power of the monarch relative to the legislature in which Euro-American business elites held disproportionate power, a political situation that was a direct result of the so-called 1887 Bayonet Constitution. The conspirators' stated goals were to depose the queen, overthrow the monarchy, and seek Hawaii's annexation to the United States.[11][12]

On January 16, the Marshal of the Kingdom, Charles B. Wilson was tipped off by detectives to the imminent planned coup. Wilson requested warrants to arrest the 13 member council, of the Committee of Safety, and put the Kingdom under martial law. Because the members had strong political ties with United States Government Minister John L. Stevens, the requests were repeatedly denied by Attorney General Arthur P. Peterson and the Queen’s cabinet, fearing if approved, the arrests would escalate the situation. After a failed negotiation with Thurston,[13] Wilson began to collect his men for the confrontation. Wilson and Captain of the Royal Household Guard, Samuel Nowlein, had rallied a force of 496 men who were kept at hand to protect the Queen.[2]

The Revolution ignited on January 17 when a policeman was shot and wounded while trying to stop a wagon carrying weapons to the Honolulu Rifles, the paramilitary wing of the Committee of Safety led by Lorrin Thurston. The Committee of Safety feared the shooting would bring government forces to rout out the conspirators and stop the coup before it could begin. The Committee of Safety initiated the overthrow by organizing the Honolulu Rifles made of about 1,500 armed local (non-native) men under their leadership, intending to depose Queen Liliʻuokalani. The Rifles garrisoned Ali'iolani Hale across the street from ʻIolani Palace and waited for the queen’s response.

As these events were unfolding, the Committee of Safety expressed concern for the safety and property of American residents in Honolulu.[14] United States Government Minister John L. Stevens, advised about these supposed threats to non-combatant American lives and property[15] by the Committee of Safety, obliged their request and summoned a company of uniformed U.S. Marines from the USS Boston and two companies of U.S. sailors to land on the Kingdom and take up positions at the U.S. Legation, Consulate, and Arion Hall on the afternoon of January 16, 1893. 162 sailors and Marines aboard the USS Boston in Honolulu Harbor came ashore well-armed but under orders of neutrality. The sailors and Marines did not enter the Palace grounds or take over any buildings, and never fired a shot, but their presence served effectively in intimidating royalist defenders. Historian William Russ states, "the injunction to prevent fighting of any kind made it impossible for the monarchy to protect itself."[16] Due to the Queen's desire "to avoid any collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life" for her subjects and after some deliberation, at the urging of advisers and friends, the Queen ordered her forces to surrender. The Honolulu Rifles took over government buildings, disarmed the Royal Guard, and declared a Provisional Government.

Aftermath

Provisional government cabinet (left to right) James A. King, Sanford B. Dole, W. O. Smith and Peter C. Jones

Provisional government cabinet (left to right) James A. King, Sanford B. Dole, W. O. Smith and Peter C. Jones

A provisional government was set up with the strong support of the Honolulu Rifles, a militia group which had defended the system of government promulgated by the Bayonet Constitution against the Wilcox Rebellion of 1889 that sought to re-establish the 1864 Constitution in which the monarchy held more power. Under this pressure, to "avoid any collision of armed forces", Liliʻuokalani gave up her throne to the Committee of Safety. Once organized and declared, the policies outlined by the Provisional Government were 1) absolute abolition of the monarchy, 2) establishment of a Provisional Government until annexation to the United States, 3) the declaration of an "Executive Council" of four members, 4) retaining all government officials in their posts except for the Queen, her cabinet and her Marshal, and 5) "laws not inconsistent with the new order of things were to continue".[12]

The Queen's statement yielding authority, on January 17, 1893, protested the overthrow:

- I Liliʻuokalani, by the Grace of God and under the Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the Constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a Provisional Government of and for this Kingdom.

- That I yield to the superior force of the United States of America whose Minister Plenipotentiary, His Excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the Provisional Government.

- Now to avoid any collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life, I do this under protest and impelled by said force yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the Constitutional Sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.

Response

United States

Newly inaugurated President Cleveland called for an investigation into the overthrow. This investigation was conducted by former Congressman James Henderson Blount. Blount concluded in his report on July 17, 1893, "United States diplomatic and military representatives had abused their authority and were responsible for the change in government." Minister Stevens was recalled, and the military commander of forces in Hawaiʻi was forced to resign his commission.[citation needed] President Cleveland stated, "Substantial wrong has thus been done which a due regard for our national character as well as the rights of the injured people requires we should endeavor to repair the monarchy." Cleveland further stated in his 1893 State of the Union Address that, "Upon the facts developed it seemed to me the only honorable course for our Government to pursue was to undo the wrong that had been done by those representing us and to restore as far as practicable the status existing at the time of our forcible intervention." The matter was referred by Cleveland to Congress on December 18, 1893 after the Queen refused to accept amnesty for the revolutionaries as a condition of reinstatement. Hawaii President Sanford Dole was presented a demand for reinstatement by Minister Willis, who had not realized Cleveland had already sent the matter to Congress — Dole flatly refused Cleveland's demands to reinstate the Queen.

The Senate Foreign Relations Committee, chaired by Senator John Tyler Morgan (D-Alabama), continued investigation into the matter based both on Blount's earlier report, affidavits from Hawaii, and testimony provided to the U.S. Senate in Washington, D.C.. The Morgan Report contradicted the Blount Report, and found Minister Stevens and the U.S. military troops "not guilty" of involvement in the overthrow. Cleveland ended his earlier efforts to restore the queen, and adopted a position of official U.S. recognition of the Provisional Government and the Republic of Hawaii which followed.[17][18]

The Native Hawaiian Study Commission of the United States Congress in its 1983 final report found no historical, legal, or moral obligation for the U.S. government to provide reparations, assistance, or group rights to Native Hawaiians.[19]

In 1993, the 100th anniversary of the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, Congress passed a resolution, which President Clinton signed into law, offering an apology to Native Hawaiians on behalf of the United States. This law is known as the Apology Resolution.

International

Every government with a diplomatic presence in Hawaii recognized the Provisional Government within 48 hours of the overthrow, including the United States, although the recognition by the United States government and its further response is detailed in the section above on "American Response". Countries recognizing the new Provisional Government included Chile, Austria-Hungary, Mexico, Russia, the Netherlands, Imperial Germany, Sweden, Spain, Imperial Japan,[20] Italy, Portugal, Britain, Denmark, Belgium, China, Peru, and France.[21] When the Republic of Hawaii was declared on July 4, 1894, immediate recognition was given by every nation with diplomatic relations with Hawaii, except for Britain, whose response came in November 1894.[22]

Provisional Government and Republic of Hawaii

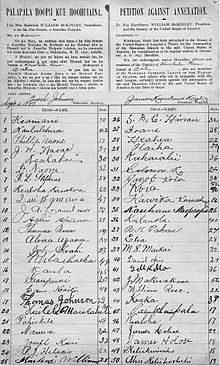

Several pro-royalist groups submitted petitions against annexation in 1898. In 1900 those groups disbanded and formed the Hawaiian Independent Party, under the leadership of Robert Wilcox, the first Congressional Representative from the Territory of Hawaii

Several pro-royalist groups submitted petitions against annexation in 1898. In 1900 those groups disbanded and formed the Hawaiian Independent Party, under the leadership of Robert Wilcox, the first Congressional Representative from the Territory of Hawaii

Sanford Dole and his committee declared itself the Provisional Government of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi on July 17, 1893, removing only the Queen, her cabinet, and her marshal from office. On July 4, 1894 the Republic of Hawaiʻi was proclaimed. Dole was president of both governments. As a republic, it was the intention of the government to campaign for annexation with the United States of America. The rationale behind annextion included a strong economic component — Hawaiian goods and services exported to the mainland would not be subject to American tariffs, and would benefit from domestic bounties, if Hawaii was part of the United States. This was especially important to the Hawaiian economy after the McKinley Act of 1890 reduced the effectiveness of the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 by raising tariffs on all foreign sugar, and eliminating Hawaii's previous advantage.

Counter-Revolution

Main article: 1895 Counter-Revolution in HawaiiA four day uprising between January 6 and 9, 1895, began with an attempted coup d'état to restore the monarchy, and included battles between Royalists and the Republic. Later, after a weapons cache was found on the palace grounds after the attempted rebellion in 1895, Queen Liliʻuokalani was placed under arrest, tried by a military tribunal of the Republic of Hawaiʻi, convicted of misprision of treason and imprisoned in her own home.

Annexation

In 1897, William McKinley succeeded Cleveland as president. A year later, he signed the Newlands Resolution which provided for the official annexation of Hawaii on July 7, 1898. The formal ceremony marking the annexation was held at Iolani Palace on August 12, 1898. Almost no Native Hawaiians attended, and those few who were on the streets wore royalist ilima blossoms in their hats or hair, and, on their breasts Hawaiian flags with the motto: Kuu Hae Aloha ("my beloved flag").[23] Most of the 40,000 Native Hawaiians, including Liliʻuokalani and the royal family, shuttered themselves in their homes, protesting what they considered an illegal transaction. "When the news of Annexation came it was bitterer than death to me", Liliuokalani's niece, Princess Ka'iulani, told the San Francisco Chronicle. "It was bad enough to lose the throne, but infinitely worse to have the flag go down..." The Hawaiian flag was lowered for the last time while the Royal Hawaiian Band played the mournful tune, Hawaiʻi Ponoʻi. One Hawaiian said "...Our beloved flag, quivered as though itself in protest of the final quavering notes of Hawaii Ponoʻi..." [24]

The Hawaiian Islands officially became Territory of Hawaii, a United States territory, with a new government established on February 22, 1900. Sanford Dole was appointed as the first governor. ʻIolani Palace served as the capitol of the Hawaiian government until 1969.

See also

- Blount Report

- 1895 Counter-Revolution in Hawaii

- Democratic Revolution of 1954

- Paulet Affair

- Unification of Hawaii

- Bayonet Constitution

- Newlands Resolution

- Kingdom of Hawaii

- Republic of Hawaii

- Apology Resolution

- Hawaiian sovereignty movement

- Kalākaua Dynasty

- Committee of Safety (Hawaii)

References

- ^ U.S. Navy History site. History.navy.mil (2005-03-22). Retrieved on 2011-07-06.

- ^ a b Young, Lucien (1899). The Real Hawaii. Doubleday & McClure company. p. 252.

- ^ Kuykendall, Ralph (1967). The Hawaiian Kingdom, Volume 3. University of Hawaii Press. p. 605. ISBN 0870224336.

- ^ Apology Resolution Excerpts. Hawaii-nation.org. Retrieved on 2011-07-06.

- ^ THE APOLOGY – United States Public Law 103-150. Hawaii-nation.org. Retrieved on 2011-07-06.

- ^ Andrade, Jr., Ernest (1996). Unconquerable Rebel: Robert W. Wilcox and Hawaiian Politics, 1880–1903. University Press of Colorado. p. 130. ISBN 0870814176.

- ^ President Cleveland'S Message. Hawaii-nation.org. Retrieved on 2011-07-06.

- ^ Russ, The Hawaiian Revolution, p. 67: She...defended her act[ions] by showing that, out of a possible 9,500 native voters in 1892, 6,500 asked for a new Constitution.

- ^ Daws, Shoal of Time, p271: The Queen's new cabinet had been in office less than a week, and whatever they thought about the need for a new constitution...they knew enough about the temper of the queen's opponents to realize that they would welcome the chance to challenge her, and no minister of the crown could look forward...to that confrontation.

- ^ Kuykendall, Ralph (1967). The Hawaiian Kingdom, Volume 3. University of Hawaii Press. p. 582. ISBN 0870224336.

- ^ Kuykendall, Ralph (1967). The Hawaiian Kingdom, Volume 3. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 533 and 587–88. ISBN 0870224336. From Kuykendall, p. 587-588: "W.D. Alexander (History of Later Years of the Hawaiian Monarchy and the Revolution of 1893, p. 37) gives the following as the wording of Thurston's motion [to launch the coup]: 'That preliminary steps be taken at once to form and declare a Provisional Government with a view to annexation to the United States.' Thurston (Memoirs, p. 250) says that his motion was 'substantially as follows: "I move that it is the sense of this meeting that the solution of the present situation is annexation to the United States."' Lt. Lucien Young (The Boston at Hawaii, p. 175) gives the following version of the motion: 'Resolved, That it is the sense of this committee that in view of the present unsatisfactory state of affairs, the proper course to pursue is to abolish the monarchy and apply for annexation to the United States.'"

- ^ a b Russ, William Adam (1992). The Hawaiian Revolution (1893–94). Associated University Presses. p. 90. ISBN 0945636539.

- ^ Twombly, Alexander (1900). Hawaii and its people. Silver, Burdett and company. p. 333.

- ^ The Morgan Report, p808-809, "At the request of many citizens, whose wives and families were helpless and in terror of an expected uprising of the mob, which would burn and destroy, a request was made and signed by all of the committee, addressed to Minister Stevens, that troops might be landed to protect houses and private property.

- ^ Kinzer, S. (2006) America's Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq. p. 30. [Minister Stevens] "certainly overstepped his authority when he brought troops ashore, especially since he knew that the 'general alarm and terror' of which the Committee of Safety had complained was a fiction."

- ^ Russ, William Adam (1992). The Hawaiian Revolution (1893–94). Associated University Presses. p. 350. ISBN 0945636431.

- ^ The Blount Report, p1342, "In reply to the direct question from Mr. Parker as to whether this was the final decision of the Senate, I said that in my opinion it was final."

- ^ Grover Cleveland's 2nd Annual Message, December 3, 1894 – "Since communicating the voluminous correspondence in regard to Hawaii and the action taken by the Senate and House of Representatives on certain questions submitted to the judgment and wider discretion of Congress the organization of a government in place of the provisional arrangement which followed the deposition of the Queen has been announced, with evidence of its effective operation. The recognition usual in such cases has been accorded the new Government."

- ^ Native Hawaiian Study Commission: See Conclusions and Recommendations p.27 and also Existing Law, Native Hawaiians, and Compensation, pgs 333–339 and pgs 341–345. Wiki.grassrootinstitute.org. Retrieved on 2011-07-06.

- ^ During the overthrow, the Japanese Imperial Navy gunboat Naniwa was docked at Pearl Harbor. The gunboat's commander, Heihachiro Togo, who later commanded the Japanese battleship fleet at Tsushima, refused to accede to the Provisional Government's demands that he strike the colors of the Kingdom, but later lowered the colors on order of the Japanese Government. Along with every other international legations in Honolulu, the Japanese Consulate-General, Suburo Fujii, quickly recognized the Provisional Government as the legitimate successor to the monarchy.

- ^ The Morgan Report, p 1103-1111. Morganreport.org (2006-02-11). Retrieved on 2011-07-06.

- ^ Andrade, Ernest (1996). The Unconquerable Rebel. The University Press of Colorado. p. 147. ISBN 0870814176. The provisional government, whatever its faults, had had little difficulty in obtaining recognition, even from Cleveland, and it was not considered likely that the republic would have any foreign problems. Recognition came even more quickly than it had in 1893, for at least there was no question of a revolution's having taken place or of the government's control of the domestic situation.

- ^ Robert W. Brockway. Hawaii "Hawai'i: America's Ally". The Spanish American War Centennial web site. http://www.spanamwar.com/Hawaii.htm Hawaii. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ Hawaii's Own. Hawaii-nation.org (1998-08-09). Retrieved on 2011-07-06.

History of Hawaii

This article is part of a seriesTimeline Ancient Kingdom of Hawaii Provisional Cession Kingdom of Hawaii Provisional Government Republic of Hawaii American Hawaii Territory State of Hawaii

Hawaii Portal

Overthrows in HawaiiKingdom of Hawaii Battle of Kuamo'o • Paulet Affair • Dominis Conspiracy • Burlesque Conspiracy • Hawaiian Revolution of 1893

Provisional Government of Hawaii Black WeekRepublic of Hawaii Uprising of 1895Territory of Hawaii State of Hawaii Statehood Day TakeoverSuccessful overthrows are in bold font.

Overthrows by a foreign power are italicized.

Failed overthrows are in normal font.Categories:- Overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii

- United States Marine Corps in the 18th and 19th centuries

- Coups

- 1890s coups d'état and coup attempts

- 1893 in Hawaii

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.