- Military history of Asian Americans

-

Asian Americans have fought on behalf of the United States since the War of 1812 until today. Due to the small population of Asian Americans in the 19th Century their contributions were not heavily recorded. In the 20th Century as the population of Asian Americans have increased contributions and documentation of their contributions have increased in kind.

Contents

- 1 History

- 2 Leadership

- 3 Military history of Asian Americans in popular culture

- 4 See also

- 5 References

- 6 External links

History

19th Century

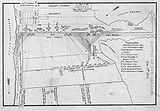

Map of Battle of New Orleans

Map of Battle of New Orleans

There is anecdotal accounts of Filipino American sailors serving as early as the revolutionary war;[1] however the first recorded history of Asian Americans fighting on behalf of the United States was recorded as far back as 1815 when General Andrew Jackson recorded "Manilamen" had fought alongside his in defense of New Orleans, under the command of Jean Baptiste Lafitte.[2] After this Asian Americans were not recorded in the annals of U.S. Military History until the American Civil War when in 1861 a Chinese American by the name of John Tomney joined the New York Infantry,[3] eventually dying of wounds received at the Battle of Gettysburg.[4]

Joseph Pierce (his chosen name) was brought to the United States from China by his adoptive father, Connecticut ship Captain Amos Peck. Pierce enlisted on July 26, 1862 and was mustered into the Fourteenth Regiment, Company F of the Connecticut Volunteer Infantry that became part of the Second Brigade of the Third Division, Second Army Corps of the Army of the Potomac.[5] From 1862 to 1865, Pierce unknowingly participated in what turned out to be many of the pivotal military events of the war, fighting in the major campaigns from Antietam[6] to Gettysburg to Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House.[7] He survived some of the bloodiest battles fought during the Civil War and is the highest known ranking (Corporal)[8] Chinese to serve in the Union Army. Pierce's picture hangs in the Gettysburg Museum.[9] Pierce was honored along with other Asian-Pacific Islander soldiers of the Civil War through a House resolution in 2008.[10]

He was to be followed by William Ah Hang in 1863, a Chinese American who became of one the first Asian Americans to enlist in the U.S. Navy.[3] In total more than 50 Chinese Americans fought, on both sides, of the Civil War.[2] Of those who have served only a handful received recognition of their service in the form of pension, benefits, or citizenship. A noted exception is Ching Lee who took the alias Thomas Sylvanus and served in 81st Pennsylvania Regiment.[11]

There are accounts of Filipino Americans serving in Louisiana for the Confederacy during the Civil War,[1] some of whom would serve in the Louisiana Zouaves.[12] That is not to say, all Filipino Americans who served were Confederates; there has been documentation of one, Felix Cornelius Balderry, serving in the Union's Michigan 11th Infantry.[13][14]

Another lull of recordings of Asian American service followed the end of the civil war until the Spanish American War. Aboard the USS Maine when she sank in Havana harbor, of the casualties seven were Japanese Americans and one was Chinese Americans.[15][16] Later in the war it was recorded that Japanese Americans served aboard US Warships in the Battle of Manila Bay;[4] the Philippine-American War, previously known as the Philippine Insurrection, followed.

20th Century

Philippine-American War

U.S.S. San Diego in 1915

U.S.S. San Diego in 1915

In 1901 the Philippine Constabulary[17] and Philippine Scouts[18] were initially founded to assist the United States against the forces of the First Philippine Republic and the insurgency that followed after its collapse. That same year President McKinley signed an executive order to allow 500 Filipinos to enlist in the U.S. Navy.[19] From these routes of enlistment came the first Asian Americans to be awarded with the United States' Medal of Honor. Private Nisperos, a Philippine Scout, was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1911 when he protected his party from Moros.[20] In 1915, Fireman Second Class Trinidad, along with Ensign Cary, was awarded the Medal of Honor for saving fellow crewmembers when the boiler of the U.S.S. San Diego exploded.[21] As of 2011, Trinidad has been the only Asian American to be awarded with the naval version of the Medal of Honor.[22][23]

Early Asian American Military Academy graduates

During this period, the first Asian Americans enrolled and graduated from the Military Academies of the United States. Although Asians had been attending Annapolis since the late 1860s they were foreign nationals, and would go on to serve their own nations' military, notably Matsumura Junzo, class of 1873, the first Asian graduate of Annapolis who would serve as a Captain in Imperial Japanese Navy.[24][25][26] Nearly forty years would pass before the first Asian Americans would follow these foreign nationals. Vicente Lim, a U.S. National at the time, graduated from West Point in the class of 1914 and would receive a commission initially in the Philippine Scouts.[27][28] He would be the first of a handful of Filipinos to enroll at West Point, as one Filipino was to be appointed in each class,[28] with no more than four enrolled at one time.[29] Beginning in 1916, Filipinos Americans were permitted to enroll in Annapolis; the first batch would enroll in 1919.[24] These graduates would lose their status as U.S. Nationals in 1935 and many would go on to serve the young Armed Forces of the Philippines.

Mexican Expedition

While the rest of the world was as in the depths of the Great War, the U.S. was looking to its south; Mexico was in the depths of its Civil War, and violence began to spill North over the border. This culminated with a U.S. response, officially known as the Mexican Expedition, which was led by Major General Pershing. Upon completion of the Expedition, against the Chinese Exclusion Act, MG Pershing was allowed to bring into the United States 527 Chinese Mexicans who assisted U.S. Forces in Mexico, and were threatened with hanging by Pancho Villa; they would go on to settle mostly in San Antonio and would become known as "Pershing's Chinese".[30]

World War I

Main article: World War IIn April 1917, the United States joined the First World War on the side of the Allies. The Philippine Islands would stand up its own national guard units to join the effort, but would not see combat. A draft was started, and alongside Hispanic and Native Americans, Asian Americans were drafted as "non-whites" filling out the "white quota" into the National Army; they too would not see combat.[31] That is not to say that no Asian Americans saw combat; Marine Private Claudio, who had studied at the University of Nevada, Reno, became the first, and only, Filipino American to die in World War I during the Battle of Château-Thierry;[32][33][34] and Sergeant Major Tokutaro Nishimura Slocum fought in the 328th Infantry Regiment, 82d Infantry Division.[35] In the Navy at its peak more than fifty-seven hundred Filipinos would enlist during World War I.[36] Many others would serve and would be allowed to become naturalized citizens,[37][38][39] but not without some difficulty,[35] or overcoming legal obstacles.[40][41]

Interwar period

Filipino Cadets being trained by a Marine on use of a M1917 Browning machine gun

Filipino Cadets being trained by a Marine on use of a M1917 Browning machine gun

The interwar period was not without incident. The U.S. was involved in the Russian Civil War, multiple events in the Caribbean that have become known as Banana Wars, the Yangtze Patrol was directly and indirectly effected by the Second Sino-Japanese War, and other events; however, there is no record of notable Asian American service members in the interwar period outside of the service academies. That is not to say that Asian Americans did not serve in the military. Between 1918 to 1933, at least 3,900 Filipinos Americans served in the U.S. Navy at any given time as mess stewards, having largely replaced African Americans in that rating.[42]

In 1934, Gordon Pai'ea Chung-Hoon became the first Asian American, U.S. Citizen, graduate of the Naval Academy,[24] this was followed in 1940 by Wing Fook Jung at West Point.[43] In 1940, Japanese Americans were the largest ethnicity of Asian Americans, followed by (in order of population) Chinese Americans, Filipino Americans, Hindu Americans, and Korean Americans.[44] For Europe this period ended in 1939, however for the United States it did not become an active and official, participant in combat until the attack on Pearl Harbor; from that point on Asian Americans were on the front lines for the U.S. Civilians of Oahu, including Japanese Americans, assisted with aid efforts following the attack;[45] on the other side of the Pacific Filipinos who were mobilized under U.S. command, since July 1941, prepared for an attack that would come nine hours later.[46]

World War II

Main article: World War IIJapanese Americans

442nd Regimental Combat Team marching in Chambois Sector, France, in late 1944

442nd Regimental Combat Team marching in Chambois Sector, France, in late 1944

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese Americans in the Hawaii National Guard were called to duty to guard the beaches, clear rubble, donate blood and aid the wounded but three days later their weapons were taken away because of their ancestry. The next day however their weapons were given back to them but an uneasy tension lasted until June 5, 1942.[47] As this uneasy tension was going on Japanese Americans who were originally a part of the ROTC program at the University of Hawaii and had enlisted Hawaii National Guard were discharged on January 19, 1942 also because of their ancestry but would soon come together to form the Varsity Victory Volunteers. It wouldn't be until June 5, 1942 when 1,400 Nisei of the Hawaii National Guard would ship out from Hawaii and eventually form the 100th Infantry Battalion on June 12, 1942 when they docked in Oakland.[48] It wouldn't be for another eight months until there would be a call for an all Nisei Regiment, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a year until the 442nd would begin training, and fourteen months until the 100th would ship out to Europe. While the 442nd was training in the United States, the 100th in the meantime would sustain heavy losses eventually earning the title the "Purple Heart Battalion." On June 26, 1944, two weeks after the 442nd arrive in Europe, the two Nisei units combine together to form one single unit but those that were a part of the 100th wanted to keep their 100th Infantry Battalion title. The other members of the 442nd RCT were Japanese Americans from the continental United States and mostly White officers.[49] Keeping with the policy at the time, the unit was a segregated one.[50] The combat chronicle of the regiment became a highly storied one, leading it to be one of the most decorated units in the European Theater,[51] including the liberation of the Dachau.[52] Additionally the Military Intelligence Service made a huge contribution to the war effort as it consisted of Japanese Americans who served in the Pacific Front and helped with the rebuilding of occupied Japan and the decoding of Japanese intelligence.[53] The second of two Asian Americans to be awarded the Medal of Honor during World War II was PFC Sadao Munemori, who was posthumously awarded for actions in Italy.

In 2000, after a review of other medals awarded to the 442nd, 21 were elevated to Medals of Honor.[54] One of those 21 was former Captain, Hawaiʻi Senator Daniel K. Inouye.[45] On October 5, 2010, the Congressional Gold Medal was awarded to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the 100th Infantry Battalion, as well as the 6,000 Japanese Americans who served in the Military Intelligence Service during the war.[55]

Chinese Americans

Chinese American soldier training at Fort Knox

Chinese American soldier training at Fort Knox

It has been estimated that 12[56] to 20 thousand,[57] possibly up to 22 percent of all Chinese Americans men, served during World War II.[58] Of those serving about 40 percent were born overseas,[2] and unlike Japanese and Filipino Americans, 75 percent served in non-segregated units.[2] A quarter of those would serve in the U.S. Army Air Force with some finding their way to the Chinese Burma India theater with the 14th Air Service Group[59] and the Chinese-American Composite Wing.[60] Another 70 percent would go on to serve in the US Army in various units, including the 3rd, 4th, 6th, 32nd and 77th Infantry Divisions.[58] The U.S. Navy had been actively recruiting Chinese Americans as Stewards even prior to the war,[60] and this continued to be the case until May 1942, when rating restrictions would be loosened and they could serve in other ratings.[60]

Captain Francis Wai of the 34th Infantry is one of the notable Chinese Americans who served during World War II; posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for actions on the island of Leyte, this awarding was elevated to a Medal of Honor in the 2000 review.[59] Wilbur Carl Sze became the first Chinese American officer commissioned in the Marine Corps.[61][62]

Filipino Americans

See also: Military history of the Philippines during World War II and Post World War II Filipino Veterans' issuesFrom the beginning, the Philippines found itself on the front lines of the new war. Under the command of General MacArthur the Philippines prepared to defend all of the islands,[63] but following the Japanese landings on Luzon, war plan orange was reinstated leading to a hasty withdrawal to the Bataan Peninsula.[64] There the Allied forces on Luzon held, with MacArthur being evacuated out of the Philippines in March 1942. In April 1942, Major General King surrendered his force that could no longer keep up a sustainable defense. Of the 75,000 that surrendered, 67,000 were Filipinos, and a thousand were Chinese Filipinos. All were then subjected to the Bataan Death March where 5,000-10,000 Filipinos died.[65] A smaller force held out on Fort Mills, however after an assault, Lieutenant General Wainwright surrendered USAFFE in May 1942.[66] Back in the U.S. Filipinos were initially blocked from enlisting, until the laws were revised a day before Japan had begun its invasion back in the Philippines.[67] Some would serve in non-segregated units,[68] yet a segregated infantry battalion was established, which at its peak would grow into two regiments known as the 1st and 2nd Filipino Infantry Regiments.[69] These units would serve with distinction similar to that of the 442d Infantry Regiment, but would not be as well documented or widely known.[15][70] It is claimed that assigned personnel of these two regiments were recipients of over fifty thousand decorations by the end of the war.[71] Back in the Philippines, some individual servicemembers and units refused to heed orders to surrender and began the guerilla resistance to the Japanese occupation, who would later be joined by parolled Filipino soldiers of USAFFE, other civilian Filipinos, and inserted forces into the islands.[72][73] The Battle of Leyte brought a return of significant allied forces back to the Philippines, including the Filipino Infantry units which had been reduced in size from its peak.[74][75] Later that year the Philippine Division was reconstituted,[76] and in 1945 those members who elected to remain in the Philippines at the end of the War were transferred to the PCAUS.[69] In all approximately 142,000 Filipinos.[77][78][79][80] When recognized recognized guerrillas are taken into account,[81][82] the number of Filipinos who served increase to over 250,000,[83][84] and possibly up to over 400,000.[85] This number though is smaller than that recognized for serving in World War II by the Philippines.[86]

Sergeant Jose Calugas became the third Asian American ever, and first Asian American during World War II, to be awarded the Medal of Honor;[87] he wouldn't receive the medal until after the occupation had ended.[88] Later in the 2000 review of Asian American service member medals, First Lieutenant Davila's Distinguished Service Cross was elevated to a Medal of Honor.[89] While in New Guinea, Lieutenant Colonel Leon Punsalang became the first Asian American to command white troops while in combat.[69][90]

Korean Americans

Koreans had been able to immigrate to the United States since a treaty was signed in 1882,[4] however that ended in 1910.[91] When the war began Korean Americans met difficulty as they were considered enemy aliens,[91] which would be repealed in 1943.[38][92][93] About 100 would enlist in the U.S. Army,[94] some of whom would serve as translators.[95] One notable Korean American service-member in World War II was Young-Oak Kim who was an officer in the 442nd Infantry Regiment.[96] He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions at the Battle of Anzio,[97] the only Korean American during the war to be awarded that medal,[98] as well as the Silver Star and Purple Heart for actions earlier in the campaign.[97]

Cold War

Post World War II

President Truman salutes the colors of the combined 100th Battalion, 442nd Infantry, during the presentation of the seventh Presidential Unit Citation.

President Truman salutes the colors of the combined 100th Battalion, 442nd Infantry, during the presentation of the seventh Presidential Unit Citation. See also: Allied-occupied Germany and Occupation of Japan

See also: Allied-occupied Germany and Occupation of JapanAfter the surrender of Japan, World War II came to an official end, and the United States began to demobilize. Millions of service-members were transported home, including the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. In 1946, they would be reviewed by President Truman awarded their seventh Distinguished Unit Citation and inactivated, only to be reorganized in the United States Army Reserve a year later.[99] With the consent of the Philippine government, fifty thousand Philippine Scouts were authorized by Congress, retained, and recruited.[100] The Philippine Division would go on to provide occupation duty on Okinawa until 1947,[101] when President Truman ordered the disbandment of the Philippine Scouts seeing it as a form of mercenary organization.[100] In 1948, President Truman ordered the desegration of the United States Military.

Korean War

Main article: Korean WarWith the integration of the U.S. Armed Forces individual all Asian American segregated units became a thing of the past, with most of the units being disbanded by 1951. Yet, many stayed on and continued to serve in integrated units; approximate numbers of Asian Americans who served during the Korean War have not been determined.[102] Some units however had a predominance of Asian Americans within their unit including the 100th Battalion, 442nd Infantry Regiment as well as the 5th Regimental Combat Team.[102][103]

One Asian American received the Medal of Honor for actions during the Korean War. Japanese American Corporal Miyamura of the 7th Infantry Regiment;[104] the awarding of this medal was initially top secret, as at the time he was being held by North Koreans as a prisoner of war.[105] Young-Oak Kim, having reenlisted then being promoted to Major, became the first ethnic minority to command a regular combat battalion, the 1st of the 31st infantry.[106]

Vietnam War

Main article: Second Indochina WarDuring the Vietnam Conflict eighty five thousand Asian Americans served out of the eight million plus total service members who would be deployed to South Vietnam,[107] in fully integrated units,[15] three of whom were posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. Sergeant First Class Yano, was one of those three who were awarded the Medal of Honor, and As of March 2011[update] has been the last Asian American recipient of that medal. Many other then-future Asian Americans would serve the military out of its normal ranks, such as Hmong and Laotian Americans who fought alongside American service members in the Laotian Civil War, Vietnamese Americans who fought as members of the South Vietnam's armed forces, and Montagnard (also known as Degar) who assisted American forces.[108] Proportionally, Asian Americans suffered less casualties compared to other ethnic groups in Vietnam,[109] with a total of 139 Asian American servicemen dying during the conflict.[110] Filipino American sailors would be restricted to the rating of Steward until the 1970s, yet many would serve regardless of the restriction.[111]

By 1989, Asian Americans were approximately 2.3 percent of the total armed services, slightly greater than their proportion of total population at that time (1.6 percent).[112]

Gulf War

Main article: Persian Gulf WarDuring the Gulf War many Asian Americans served, with some being promoted to senior officer positions,[113] including the MG Fugh who was promoted to the position of Army Judge Advocate General during the conflict.[114][115] One Asian American serviceman died during the conflict.[110]

21st Century

Asian American service members at a Defense Department's Asian Pacific American Heritage Month luncheon in Arlington, VA.

Asian American service members at a Defense Department's Asian Pacific American Heritage Month luncheon in Arlington, VA.

Asian Americans had historically been less likely to join the Military, but recent trends show that Asian Americans, particular in California, are enlisting at rates greater than their proportion of population; they are more likely to take up non-combat jobs.[116] In 2009, the Army had Asian Americans serving as 4.4 percent of its commissioned officers, and 3.5 percent of its enlisted personnel.[117]

War on Terrorism

Main article: War on TerrorAs of 28 February 2011[update], out of the 1,477 deaths that have occurred in Operation Enduring Freedom, 25 have been Asian Americans; except for 4 of these deaths, the service-members were Soldiers.[118] An additional 178 Asian American service-members have been wounded.[119]

Afghanistan

Main article: Operation Enduring Freedom - AfghanistanAsian American Marines were part of the first conventional units to enter into Afghanistan in late 2001.[120] During Operation Red Wings in 2005, Petty Officer 2nd Class James Suh, a Navy SEAL, was KIA when the MH-47 he was on crashed after being hit by an RPG.[121]

Other Theaters

Iraq War

Main article: Operation Iraqi FreedomHundreds of Asian Americans have deployed to Iraq out of the fifty nine thousand (59,000) plus that are serving in active duty as of May 2009,[122][123] with one study stating that 2.6 percent have been Asian American.[124] The 100th Infantry Battalion (USAR) were activated for their first deployment in 2004 to serve in Iraq,[125][126] their first activation since the Vietnam Conflict.[127][128] At the end of that deployment the unit was authorized to wear the 442nd's shoulder sleeve insignia as a combat patch, the first time this had occurred since World War II.[129][130] It was activated and deployed a second time from 2008 to 2009.[131][132] With the end of Operation Iraqi Freedom having ended, and Operation New Dawn taking its place, eighty two (82) Asian American service members died during the conflict.[133]

Leadership

The first Asian American general was Brigadier General Albert Lyman,[134] who was part Chinese and Hawaiian American. He was followed by Rear Admiral Gordon Chung-Hoon, the first Asian American flag officer.[135] As of June 2010[update], there have been 43 Japanese American, 26 Chinese Americans, 10 Filipino American, and four Korean American general and flag officers in the Uniformed services of the United States.[136] The highest ranked of these is Secretary of Veteran Affairs Eric Shinseki, who was a four-star General, and Army Chief of Staff.[137]

In recent years, Asian Americans have been significantly overrepresented at the military academies compared to their share of the national population. Although Asian/Pacific Islander Americans are 3.49% of the national population aged 18–24,[138] they are about 9-10% of the classes of 2014 at West Point,[139] the Naval Academy,[140] and the Air Force Academy.[141]

Military history of Asian Americans in popular culture

The following television shows, movies, and songs have depicted events which relate to this article:

See also

- 12th Infantry Division

- 442d Infantry Regiment

- History of Asian Americans

- List of Asian American Medal of Honor recipients

- List of notable Asian American servicemembers

- Military history of African Americans

- Military history of Hispanic and Latino Americans

- Military history of Jewish Americans

- Military history of Sikh Americans

- Military history of the United States

- Native Americans in the American Civil War

- Native Americans and World War II

- Philippine Constabulary

- Philippine National Guard

- Philippine Scouts

- Vietnamese American Armed Forces Association

- USS Lanikai

- USS Rizal

References

- ^ a b Rodel E. Rodis. "Filipinos in Louisiana". Global Nation. www.inq7.net. http://www.inquirer.net/globalnation/col_gln/2005/oct03.htm. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d Williams, Rudi (3 June 2005). "DoD's Personnel Chief Gives Asian-Pacific American History Lesson". American Forces Press Service (U.S. Department of Defense). http://www.defenselink.mil/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=16498. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- ^ a b Williams, Rudi (1999). "Asian/Pacific American Military Timeline". Memorial Day, 1999. Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute. http://www.chcp.org/memorialday.html. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- ^ a b c Williams, Rudi (19 May 1999). "An Asian Pacific American Timeline". American Forces Press Service (U.S. Department of Defense). http://www.defenselink.mil/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=43031. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ^ "Soldiers Biographies, Page 3". Gettysburg National Military Park. National Park Service. http://www.nps.gov/archive/gett/getteducation/bcast04/sold-bios3.htm. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ "Civil War". United States Army. http://www.army.mil/asianpacificsoldiers/history/civilwar.html. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ Daniel Saxton (2008). "Appomattox Court House". State of the Parks. National Parks Conservation Association. http://www.npca.org/stateoftheparks/appomattox/APCO-full-report-web.pdf. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ Stephen Heidler, David; Jeanne T. Heidler, David J. Coles (2002). Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: a political, social, and military history. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 434. ISBN 9780393047585. http://books.google.com/books?id=SdrYv7S60fgC&pg=PA434&lpg=PA434&dq=Corporal+Joseph+Pierce+chinese&source=bl&ots=lX0CyOQyHC&sig=8ReYYt6MEl64HDECB6WLcho4Uak&hl=en&ei=CoozTcHRGorCsAPn5ozWBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=8&ved=0CEsQ6AEwBw#v=onepage&q=Corporal%20Joseph%20Pierce%20chinese&f=false. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ "Joseph Pierce,". http://www.gdg.org/Research/People/jpierce.html. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ "H. Res. 415 [110th: Honoring Edward Day Cohota, Joseph L. Pierce, and other veterans of Asian and Pacific Islander... (GovTrack.us)"]. Honoring Edward Day Cohota, Joseph L. Pierce, and other veterans of Asian and Pacific Islander descent who fought in the United States Civil War.. 110th Congress 2007-2008. http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=hr110-415. Retrieved 30 ZMay 2011.

- ^ Lin, Sam Chu. "Chinese American Civil War Veteran Honored In Pennsylvania Ceremonies". Articles of Interest. Committee of 100, inc.. http://www.committee100.org/media/media_eng/sam_chu_lin.html. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ^ O'Donnell-Rosales, John (2006). Hispanic Confederates. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Com. p. ix. ISBN 9780806352305. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jsuy2CLtuD0C&lpg=PR9&ots=EmtaY__lLC&dq=Confederacy%20Filipino%20Americans%20Louisiana&pg=PR9#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Brett Wishe (2 November 2010). "Filipinos display proud heritage exhibit at Five Corners Library". The Jersey Journal. http://www.nj.com/hudson/index.ssf/2010/11/filipinos_display_proud_herita.html. Retrieved 19 May 2011. "Filled with photos and mini-essays, including old newspaper documents, it chronicles the roles of influential Filipino-Americans, from San Francisco Giants pitcher Tim Lincecum to Felix Cornelius Balderry, a Union soldier in the Civil War."

- ^ Dempsey, Jack (2011). Michigan and the Civil War: A Great and Bloody Sacrifice. Charleston, SC: The History Press. p. 88. ISBN 9781609491734. http://books.google.com/books?id=on6b2Pcl1lIC&lpg=PA88&ots=QVjBoYsdR3&dq=Felix%20Balderry%20civil%20war%20michigan&pg=PA88#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ a b c "A Review of Data on Asian Americans". Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute. Department of Defense. August 1998. http://www.deomi.org/downloadableFiles/rodap98.pdf. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ VADM J.C. Harvey Jr. (18 April 2007). "RAAUZYUW RUENAAA7101 1082000-UUUU--RUCRNAD". United States Navy. http://www.public.navy.mil/bupers-npc/reference/messages/Documents/NAVADMINS/NAV2007/NAV07091.txt. Retrieved 29 May 2011. "SEVEN FIRST-GENERATION JAPANESE AMERICANS AND ONE CHINESE AMERICAN WERE KILLED WHEN THE USS MAINE WAS SUNK IN HAVANA HARBOR IN 1898."

- ^ "PNP History". Philippine National Police. Philippine Department of Interior and Local Government. http://www.pnp.gov.ph/about/content/history.html. Retrieved 29 August 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Olson, John E. (11 May 2007). "The History of the Philippine Scouts". History. Philippine Scouts Heritage Society. http://www.philippine-scouts.org/history/history-of-the-scouts.html. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ Hooker, J.S. (October 1976). "Filipinos in the United States Navy". Naval Historical Center. Department of the Navy. http://www.history.navy.mil/library/online/filipinos.htm. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- ^ "United States Army Center of Military History Medal of Honor Citations Archive". American Medal of Honor recipients for the Philippine Insurrection. United States Army Center of Military History. June 8, 2009. http://www.history.army.mil/html/moh/philippine.html. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ George J., Albert. "The U.S.S. San Diego and the California Naval Militia". The California State Military Museum. California State Military Department. http://www.militarymuseum.org/USSSanDiego.html. Retrieved 22 September 2009. and

"Medal of Honor RecipientsInterim Awards, 1915-1916". Center of Military History. United States Army. 3 August 2009. http://www.history.army.mil/html/moh/interim1915-16.html. Retrieved 22 September 2009. - ^ Rodney Jaleco (19 October 2010). "Pinoy WWII vets still top Fil-Am concern". ABS-CBN. http://www.abs-cbnnews.com/global-filipino/10/19/10/pinoy-wwii-vets-still-top-fil-am-concern. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ "Asian and Pacific Island American Heritage". Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute. 1998. http://www.deomi.org/downloadableFiles/ap98.pdf. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Gelfand, H. Michael (2006). Sea change at Annapolis: the United States Naval Academy, 1949-2000, Volume 415. UNC Press. p. 48. ISBN 080783047X. http://books.google.com/books?id=dJDHptZWHUUC&lpg=PA48&ots=KTHcc3pCFW&dq=first%20filipino%20graduate%20usna&pg=PA48#v=onepage&q=first%20filipino%20graduate%20usna&f=false. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- ^ Beasley, William (1995). Japan encounters the barbarian: Japanese travellers in America and Europe. Yale University Press. p. 135. ISBN 0300063245. http://books.google.com/books?id=X8qI7vtqcMEC&lpg=PA134&ots=pg_-HVu5jR&dq=%22Matsumura%20Junzo%22&pg=PA135#v=onepage&q=Annapolis&f=false. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- ^ Griffis, William Elliot (1876). The Mikado's Empire. New York: Harper. p. 8. http://www.archive.org/stream/themikadosempire00grifiala/themikadosempire00grifiala_djvu.txt. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- ^ García, Florentino Rodao; Florentino Rodao, Felice Noelle Rodríguez (2001). The Philippine revolution of 1896: ordinary lives in extraordinary times. Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 110. ISBN 9715503861. http://books.google.com/books?id=l533SkJ2VCkC&lpg=PA110&ots=2i96UKWLMm&dq=Vicente%20Lim%20%22west%20point%22&pg=PA110#v=onepage&q=Vicente%20Lim%20%22west%20point%22&f=false. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- ^ a b Annual report of the Secretary of War. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1915. p. 11. http://books.google.com/books?id=To0sAAAAIAAJ&lpg=PP25&ots=sjqTjAlLeQ&dq=1910%20Filipino%20West%20Point&pg=PP25#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ The World almanac and book of facts. Newspaper Enterprise Association. 1914. p. 423. http://books.google.com/books?id=-GQ3AAAAMAAJ&lpg=PA423&ots=FXWVLKddwm&dq=1910%20Filipino%20West%20Point&pg=PA423#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ Stacy, Lee (2002). Mexico and the United States. 0761474021: Marshall Cavendish. p. 182. ISBN 0761474021. http://books.google.com/books?id=DSzyMGh8pNwC&lpg=PA182&dq=chinese&pg=PA182#v=onepage&q=chinese&f=false. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- ^ Allerfeldt, Kristofer (January 2009). "Work or Fight!". Reviews in History. The Institute of Historical Research. http://www.history.ac.uk/reviews/paper/allerfeldtk.html. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- ^ Zena Sultana-Babao, America’s Thanksgiving and the Philippines’ National Heroes Day: Two Holidays Rooted in History and Tradition, Asian Journal, http://asianjournalusa.com/default.asp?sourceid=&smenu=141&twindow=&mad=&sdetail=3692&wpage=1&skeyword=&sidate=&ccat=&ccatm=&restate=&restatus=&reoption=&retype=&repmin=&repmax=&rebed=&rebath=&subname=&pform=&sc=1028&hn=asianjournalusa&he=.com, retrieved 2008-01-12

- ^ Sol Jose Vanzi (3 June 2004). "BALITANG BETERANO: FACTS ABOUT THE PHILIPPINE INDEPENDENCE". Philippine Headline News Online. http://www.newsflash.org/2004/02/tl/tl012375.htm. Retrieved 16OCT09.

- ^ "Schools, colleges and Universities: Tomas Claudio Memorial College". Manila Bulletin Online. Archived from the original on 2007-07-07. http://web.archive.org/web/20070707015924/http://www.mb.com.ph/issues/2007/01/25/SCAU2007012585502.html. Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- "Thomas Claudio Memorial College". www.tcmc.edu.ph. http://www.tcmc.edu.ph/. Retrieved 2007-07-04. - ^ a b Salyer, Lucy (December 2004). "Baptism by Fire: Race, Military Service, and U.S. Citizenship Policy, 1918–1935". The Journal of American History 91 (3). http://www.historycooperative.org/cgi-bin/justtop.cgi?act=justtop&url=http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/jah/91.3/salyer.html. Retrieved 4 September 2004.

- ^ Kramer, Paul Alexander (2006). The blood of government: race, empire, the United States, & the Philippines. UNC Press. p. 384. ISBN 9780807856536. http://books.google.com/books?id=e2OIAj3cp7wC&lpg=PA384&ots=u3vDK9_r_6&dq=all%20filipino%20crew%20united%20states%20navy&pg=PA384#v=onepage&q=all%20filipino%20crew%20united%20states%20navy&f=false. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ^ "World War I". Asian Pacific Americans. United States Army. http://www.army.mil/asianpacificsoldiers/history/worldwar1.html. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- ^ a b "LANDMARKS IN ASIAN AMERICAN HISTORY IN THE UNITED STATES". Presidential Task Force on Asian American. Northern Illinois University. 2001. http://www3.niu.edu/ptaa/history.htm. Retrieved 22 November 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Chan, Sucheng (1991). Asian Americans: an interpretive his. Twayne. p. 196. ISBN 9780805784374. http://books.google.com/books?ei=PxBuTcKmK4O0sAPb3cS2Cw&ct=result&id=P9Zro9x6mZQC&dq=Asian+Americans,+an+Interpretive+History&q=citizen+world+war#search_anchor. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Bhagat Singh Thind". Public Broadcasting System. 2000. http://www.pbs.org/rootsinthesand/i_bhagat1.html. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ "Japanese Americans in America's Wars: A Chronology". Japanese American National Museum. http://www.janm.org/nrc/militarych.php. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ Solliday, Scott; Vince Murray (2007). The Filipino American Community (Report). City of Phoenix. http://www.azhistory.net/aahps/f_filipino_etc.pdf. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Graham, Sylvia (2005). "Firsts & Lasts at USMA". Register of Graduates and Former Cadets. United States Military Academy. http://www.westpointaog.org/NetCommunity/Document.Doc?id=480. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- ^ Truesdell, Leon (1943). "Population, Characteristics of the nonwhite population by race". Sixteenth Census of the United States:1940. United States Department of Commerce. http://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/41271189.pdf. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ a b Kim, Hyung-chan (1999). Distinguished Asian Americans: a biographical dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 135. ISBN 0313289026. http://books.google.com/books?id=prhRl6DYXRMC&lpg=PA135&ots=E_5FueH6pX&dq=pearl%20harbor%20inouye%201971&pg=PA135#v=onepage&q=pearl%20harbor%20inouye%201971&f=false. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ^ "Philippine Islands". Center of Military History. U.S. Army. 3 October 2003. http://www.history.army.mil/brochures/pi/pi.htm. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ "100th INFANTRY BATTALION". History. Go For Broke National Education Center. http://goforbroke.org/history/history_historical_veterans_100th.asp. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "TIMELINE". History. Go For Broke National Education Center. http://goforbroke.org/history/history_historical_timeline_1942.asp. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Pike, John (23 May 2005). "100th Battalion, 442nd Infantry". Military. GlobalSecurity.org. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/100-442in.htm. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ Nakagawa, Martha. "In Times of War". Rights of Passage. Community Television of Southern California. http://kcet.org/explore-ca/web-stories/ritesofpassage/duty/essay.php. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ "100th Battalion, 442d Infantry". Center of Military History. U.S. Army. 3 August 2009. http://www.history.army.mil/html/topics/apam/100bn_442inf.html. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ "CENTRAL EUROPE CAMPAIGN - (522nd FIELD ARTILLERY BATTALION)". History. Go For Broke National Education Center. http://www.goforbroke.org/history/history_historical_campaigns_central.asp. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ "Military Intelligence Service Research Center". Military Intelligence Service Association of Northern California. 2003. http://www.njahs.org/misnorcal/. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ "Asian Pacific American World War II". Medal of Honor Recipients. United States Army Center of Military History. June 8, 2009. http://www.history.army.mil/html/moh/ap-moh1.html. Retrieved August 25, 2009.

- ^ Steffen, Jordan (October 6, 2010), "White House honors Japanese American WWII veterans", The Los Angeles Times, http://www.latimes.com/news/nationworld/nation/la-na-veterans-medal-20101006,0,7017069.story

- ^ Wong, Kevin Scott (2005). Americans first: Chinese Americans and the Second World War. Harvard University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780674016712. http://books.google.com/books?id=wex-8MBRkKYC&lpg=PA50&ots=EBq45e5dhV&dq=%22Chinese%20Americans%22%20%22World%20War%20II%22&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q=%22Chinese%20Americans%22%20%22World%20War%20II%22&f=false. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ "One Fifth of Chinese Americans Fight Fascism in World War II". Xinhua News Agency. 28 May 2001. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-18366243.html. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ a b "World War II/Post War Era". Timeline. Oakland Museum of California. http://www.museumca.org/picturethis/4_7.html. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ a b James C. McNaughton (3 August 2009). "Chinese-Americans in World War II". Center of Military History. United States Army. http://www.history.army.mil/html/topics/apam/chinese-americans.html. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ a b c Wong, Kevin Scott (2005). Americans first: Chinese Americans and the Second World War. Harvard University Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780674016712. http://books.google.com/books?id=wex-8MBRkKYC&lpg=PA50&ots=EBq45e5dhV&dq=%22Chinese%20Americans%22%20%22World%20War%20II%22&pg=PA61#v=onepage&q=%22Chinese%20Americans%22%20%22World%20War%20II%22&f=false. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ Major Karen J. Gregory, USAFR. "Asian Pacific American Heritage Month". Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute. http://www.deomi.org/SPECIALOBSERVANCE/documents/Asian_Pacific_American_Heritage_Month_Facts_of_the_Day.pdf. Retrieved 31 May 2011. "On December 15, 1943, Wilbur Carl Sze was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant and the first Chinese-American officer in the U.S. Marine Corps"

- ^ "apa-usmc02". Asian Pacific American Heritage Month 2002. Department of Defense. 2002. http://www.defense.gov/specials/asianpacific2002/apa-usmc02.html. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ Louis Morton. "Chapter 6". Center of Military History. United States Army. http://www.history.army.mil/books/70-7_06.htm. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ^ Merriam, Ray (1999), War in the Philippines, Merriam Press, pp. 70–82, ISBN 1-57638-164-1, http://books.google.com/books?id=utbD8wwF91kC&pg=PA70&lpg=PA70&dq=26th+cavalry&source=web&ots=PGuA3JpiEt&sig=upw4pWSJRiZX7uT_ys6d-snEGss#PPA70,M1, retrieved 2008-01-31

- ^ Gordon, Maj. Richard M., (U.S. Army, retired) (October 28, 2002). "Bataan, Corregidor, and the Death March: In Retrospect". http://home.pacbell.net/fbaldie/In_Retrospect.html. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ^ "General Jonathan Wainwright". Army Medical Department and Regiment. United States Army. http://ameddregiment.amedd.army.mil/fshmuse/wainwright.htm. Retrieved 12 November 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Frank, Sarah (2005). Filipinos in America. Lerner Publications. p. 37. ISBN 9780822548737. http://books.google.com/books?id=9Yr-p5T54qEC&lpg=PA37&ots=Tuyv5ydKXH&dq=%22First%20Filipino%20Regiment%22&pg=PA37#v=onepage&q=%22First%20Filipino%20Regiment%22&f=false. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ^ Doroteo V. Vite. "A Filipino Rookie In Uncle Sam's Army". Asian American Studies 456 Filipinos In America Course Reader. San Francisco State University. http://userwww.sfsu.edu/~gonzo1/files/456/456_READER_2004S.pdf. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ^ a b c Alex S. Fabros. "California's Filipino Infantry". The California State Military Museum. California State Military Department. http://www.militarymuseum.org/Filipino.html. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ^ Nakano, Satoshi (2004). "The Filipino World War II veterans equity movement and the Filipino American community". Seventh Annual International Philippine Studies (Center for Pacific And American Studies). http://www.cpas.c.u-tokyo.ac.jp/pub/PAS6_Nakano_133-58.pdf. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Andrew Ruppenstien; Manny Santos (21 January 2010). "The First and Second Filipino Infantry Regiments U.S. Army". Historic Marker Database. http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=28040. Retrieved 10 May 2011. "Personnel won more than 50,000 decorations, awards, medals, ribbons, certificates, commendations and citations."

- ^ "The Guerrilla War". MacArthur. PBS. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/macarthur/sfeature/bataan_guerrilla.html. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ^ Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Us Special Warfare Units in the Pacific Theater 1941-45. Osprey Publishing. pp. 96. ISBN 9781841767079. http://books.google.com/books?id=sMnCNdLO888C&lpg=PA41&ots=7OPS3qfLis&dq=5217th%20Reconnaissance%20Battalion&pg=PA40#v=onepage&q=5217th%20Reconnaissance%20Battalion&f=false. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ Scott Ishikawa (30 November 2001). "New film depicts Filipino regiments' exploits". Honolulu Advertiser. http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2001/Nov/30/ln/ln03a.html. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ Frank, Sarah (2005). Filipinos in America. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Lerner Publications. p. 39. ISBN 9780822548737. http://books.google.com/books?id=9Yr-p5T54qEC&lpg=PA37&ots=Tvtu8DiHSC&dq=%22Filipino%20Infantry%20regiment%22&pg=PA39#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ (Nota Bene: These combat chronicles, current as of October 1948, are reproduced from The Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the Army of the United States, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1950, pp. 510-592.)

- ^ "Filipino Americans". Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs. The State of Washington. http://www.capaa.wa.gov/community/filipino_americans.shtml. Retrieved 12 November 2009.[dead link]

- ^ J. Michael Houlahan (11 May 2007). "Post World War II Philippine Scouts". History. Philippine Scouts Heritage Society. http://www.philippine-scouts.org/history.html. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ Senator Daniel Akaka (25 July 1997). "Statement on Senator Daniel K. Akaka before the Senate Veterans' Affairs committee hearing on pending legislation". Senator Daniel Akaka. United States Senate. http://akaka.senate.gov/statements-and-speeches.cfm?method=releases.view&id=70972a30-b1fc-46d1-8390-df63eba8a217. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Emelyn Cruz Lat (25 May 1997). "Aging Filipinos who fought for U.S. live lonely lives waiting for promises to be kept". San Francisco Examiner. http://articles.sfgate.com/1997-05-25/news/28568977_1. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ "VA Benefits for Filipino Veterans". United States Department of Veterans Affairs. April 2008. http://www.va.gov/opa/publications/factsheets/fs_filipino_veterans.pdf. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ "Philippine Army and Guerrilla Records". National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis. The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. http://www.archives.gov/st-louis/military-personnel/philippine-army-records.html. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Virginia Yap Morales, Maria (2006). Diary of the war: World War II memoirs of Lt. Col. Anastacio Campo. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 198. ISBN 9789715504898. http://books.google.com/books?id=oPPh-Of8sEwC&lpg=PP1&vq=750%2C000&pg=PA198#v=snippet&q=250000&f=false. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Canonizado Buell, Evengeline; Evelyn Luluguisen, Lillian Galedo, Eleanor Hipol Luis (2008). Filipinos in the East Bay. Arcadia Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 9780738558325. http://books.google.com/books?id=m4cagVAo5D0C&lpg=PA8&vq=250%2C000&pg=PA8#v=snippet&q=250,000&f=false. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ "Asian Heritage in the National Park Service Cultural Resources Programs". National Park Service. http://www.cr.nps.gov/crdi/publications/Asianisms-chapter4.pdf. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Jaleco, Rodney (4 August 2010). "Excluded Fil-Vets Now Eligible for Lump-Sum Money". Balitang America (ABS-CBN). http://www.abs-cbnnews.com/pinoy-migration/balitang-america/03/28/09/excluded-fil-vets-now-eligible-lump-sum-money. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Sterner, C. Douglas (2007). Go For Broke: The Nisei Warriors of World War II Who Conquered Germany. Clearfield, Utah: American Legacy Media. pp. 134–135. ISBN 9780979689611. http://books.google.com/books?id=teeObc0NHUAC&lpg=PA134&dq=Jose%20Calugas&pg=PA134#v=onepage&q=Jose%20Calugas&f=false. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Carole Beers (24 January 1998). "Jose Calugas, Medal of Honor Winnier 'Death March' Survivor". The Seattle Times. http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19980124&slug=2730347. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ RICHARD GOLDSTEIN (11 February 2002). "Rudolph Davila, 85, Recipient of Highest Award for Valor". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2002/02/11/us/rudolph-davila-85-recipient-of-highest-award-for-valor.html. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Dr. Steven M. Graves. "Geography 417". Geography 417. California State University, Northridge. http://www.csun.edu/~sg4002/courses/417/417_lectures/417_post_war.htm. Retrieved 18 May 2011. "Lt. Col. Leon Punsalang, a West Point graduate, command of the 1st Battalion marking the first time in that an Asian American commanded white troops in combat."

- ^ a b Carey Giudici (31 May 2001). "Korean Americans in King County". Cyberpedia Library. HistoryLink.org. http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=3251. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ^ May Chow (10–16 January 2003). "Korean American History". Asian Week. http://asianweek.com/2003_01_10/feature_timeline.html. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Armstrong, Charles K. (2007). The Koreas. New York, New York: CRC Press. p. 104. ISBN 9780415948531. http://books.google.com/books?id=_mh4Qv4lAkQC&lpg=PT116&ots=sNpl1eOQMv&dq=Military%20Order%20No.%2045%20Korean%20Americans&pg=PT116#v=onepage&q=Military%20Order%20No.%2045%20Korean%20Americans&f=false. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Kim Young Sik, Ph.D. (9 November 2003). "The Korean Americans in the War of Independence". East Asia. Association for Asia Research. http://www.asianresearch.org/articles/1633.html. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ^ Taus-Bolstad, Stacy (2005). Koreans in America. Lerner Publications. p. 45. ISBN 9780822548744. http://books.google.com/books?id=g6Tw_NPEe58C&lpg=PA45&ots=NK8l58CyDY&dq=%22Korean%20americans%22%20World%20War%20II&pg=PA45#v=onepage&q=%22Korean%20americans%22%20World%20War%20II&f=false. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ^ "PODCASTS". Oral History. Go For Broke National Education Center. http://www.goforbroke.org/oral_histories/oral_histories_hanashi_podcast.asp. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ^ a b Gregg K. Kakesako (4 January 2006). "Soldier embodied bravery of 100th Battalion vets". Honolulu Star Bulletin. http://archives.starbulletin.com/2006/01/04/news/story09.html. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ^ C. Douglas Sterner. "Anzio and the Road to Rome". HomeOfHeroes.com. http://www.homeofheroes.com/moh/nisei/index5_anzio.html. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ^ Global Security.org "100th Battalion, 442nd Infantry". GlobalSecurity.org. 2005-05-23. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/100-442in.htm Global Security.org. Retrieved 2008-09-27.

- ^ a b Wilson, John B.; Jeffrey J. Clarke (1998). MANEUVER AND FIREPOWER. Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army. p. 212. http://www.history.army.mil/books/lineage/M-F/chapter8.htm. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ^ Triplet, William S.; Robert H. Ferrell (2001). In the Philippines and Okinawa: a memoir, 1945-1948. University of Missouri Press. pp. 299. ISBN 9780826213358. http://books.google.com/books?id=h5x7wobGXI0C&dq=new+philippine+scouts+ryukyu&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ a b "Asian-Americans i the United States Military during the Korean War". State of New Jersey. http://www.state.nj.us/military//korea/factsheets/asian.html. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ^ Boose Jr., Donald W. (2002). "Hills of Sacrifice: The 5th RCT in Korea". Korean Studies 26 (2): 316–318. Archived from the original on 2002. http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals/korean_studies/v026/26.2boose02.pdf. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ^ Lou Hoffman. "History: Korean War". The New Mexico Veterans' Memorial, Museum, & Conference Center. City of Albuquerque.

- ^ United States Congress (22 March 2001). "AMERICA'S FIRST TOP SECRET HERO". Congressional Record. http://www.fas.org/sgp/congress/2001/s032201.html. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ^ Mary Graybill. "COLONEL YOUNG OAK KIM (U.S. ARMY RET.), 86; DECORATED US WWII AND KOREAN WAR VETERAN". PRESS RELEASES. Go For Broke National Education Center. http://www.goforbroke.org/about_us/about_us_news_press010306.asp. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- ^ Janet Dang (3–9 December 1998). "The Wounds of War-And Racism". AsianWeek. http://asianweek.com/120398/coverstory.html. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ Kelly, Francis John (1989) [1973]. History of Special Forces in Vietnam, 1961-1971. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. pp. 6–7. CMH Pub 90-23. http://www.history.army.mil/BOOKS/Vietnam/90-23/90-23C.htm.

- ^ Michael Kelley (July 1998). "Myths & Misconceptions: Vietnam War Folklore". The Vietnam Conflict. De Anza College. http://www.deanza.edu/faculty/swensson/essays_mikekelley_myths.html. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ a b Hannah Fischer (13 July 2005). "American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics". Navy Department Library. United States Navy. http://www.history.navy.mil/library/online/american%20war%20casualty.htm. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Farolan, Ramon (21 July 2003). "From Stewards to Admirals: Filipinos in the U.S. Navy". Asian Journal. http://news.newamericamedia.org/news/view_article.html?article_id=3aa56896ce0e9bc13f9afc78829530d0. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- ^ LtCol F. T. Fowler (December 1989). "ASIAN-PACIFIC-AMERICAN HERITAGE WEEK - 1990". Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute. Department of Defense. http://www.deomi.org/downloadableFiles/ap1990.pdf. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ "Gulf War". Army.mil features. United States Army. http://www.army.mil/asianpacificsoldiers/history/gulfwar.html. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ St. Louis Chinese American News. "Accomplished Chinese American: John Liu Fugh". Archive. St. Louis Chinese American News. http://www.scanews.com/spot/2003/june/s667/english-news/caf-news.txt. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Adam Bernstein (12 May 2010). "Maj. Gen. John L. Fugh, 75, dies; served as Army's judge advocate general". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/05/11/AR2010051104818.html. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ LONNY SHAVELSON (21 June 2010). "More Asian-Americans Signing Up For The Army". NPR. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=127986892. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Dr/ Betty D. Maxfield (September 30, 2009). "FY09 Army Profile". Headquarters, Department of the Army. United States Army. http://www.2k.army.mil/downloads/FY09%20Army%20Profile.pdf. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ "Operation Enduring Freedom: Military Deaths". Defense Manpower Data Center. United States Department of Defense. 28 February 2011. http://siadapp.dmdc.osd.mil/personnel/CASUALTY/oefdeaths.pdf. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ "Operation Enduring Freedom: Military Deaths". Defense Manpower Data Center. United States Department of Defense. 28 February 2011. http://siadapp.dmdc.osd.mil/personnel/CASUALTY/oefwia.pdf. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ Swing, Peter J. (2001). "Reflections of War and a Makeshift Altar". Hyphen Magazine (Independent Arts & Media) (22). http://www.hyphenmagazine.com/magazine/issue-22-throwback/reflections-war-and-makeshift-altar?quicktabs_1=2. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ "James Suh". Memorial. NavySEALs.com. http://www.navyseals.com/james-suh. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Democrats Advancing the State of Our Union for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders". Democratic Policy Committee. United States Senate. 26 January 2007. http://dpc.senate.gov/dpcdoc.cfm?doc_name=fs-110-1-14. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ "Report: Racism towards Asian Americans persists". San Diego News Network. 13 May 2009. http://www.sdnn.com/sandiego/2009-05-13/business-real-estate/report-racism-towards-asian-americans-persists. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Ricardo E. Jorge, MD (1 June 2008). "Mood and Anxiety Disorders Following Traumatic Brain Injury: Differences Between Military and Nonmilitary injuries". Psychiatric Times. Archived from the original on 24 March 2011. http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:ifnOJ4xqRqwJ:www.psychiatrictimes.com/display/article/10168/1163519%3FpageNumber%3D2+%22Asian+american%22+Operation+Enduring+Freedom+Afghanistan&cd=9&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us&source=www.google.com. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ Harold P. Estabrooks (21 August 2005). "100th Battalion's values live on in Iraq". The Honolulu Advertiser. http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2005/Aug/21/op/FP508210304.html. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ William Cole (3 October 2004). "'Go For Broke' battalion swells with pride as it readies for war". The Honolulu Advertiser. http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2004/Oct/03/ln/ln05a.html. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ "Lineage And Honors Information: 100th Battalion, 442nd Infantry Regiment". U.S. Army Center of Military History. United States Army. 14 January 2011. http://www.history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/lineages/branches/inf/0442in100bn.htm. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Gregg K. Kakesako (25 December 2005). "100th Battalion marks Yule in Iraq". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Archived from the original on 19 February 2011. http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:http://archives.starbulletin.com/2005/12/25/news/story09.html. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Terry Shima (23 January 2006). ""Go for broke" battalion returns home from second overseas combat mission. Made significant contributions to defeat terrorism and to democratize Iraq". Japanese American Veterans Association. http://www.javadc.org/Press%20Release%2001-23-2006%20Go%20for%20Broke%20Bn%20Rtns%20Home.htm. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ William Cole (24 March 2006). "Hawaii Guard troops can keep combat patches". Army Times. http://www.armytimes.com/legacy/new/1-292925-1641505.php. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Ted Tsukiyama. "100th Infantry Battalion". History. National Veterans Network. http://www.nationalveteransnetwork.com/history100th.html. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ "Gold medal honors, inspires". Honolulu Star Advertiser. 7 October 2010. http://www.staradvertiser.com/editorials/20101007_Gold_medal_honors_inspires.html. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Hannah Fischer (28 September 2010). "U.S. Military Casualty Statistics: Operation New Dawn, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation Enduring Freedom". Congressional Research Service. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RS22452.pdf. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Lisa Wong Macabasco (22 January 2008). "Lyman Brothers, First Asian Americans to Gain General’s Rank". Asian Week. http://www.asianweek.com/2008/01/22/lyman-brothers-first-asian-americans-to-gain-general%E2%80%99s-rank/. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ "Asians Asians and Pacific Islanders and in the United States Navy". Naval History & Heritage Command. United States Navy. 12 April 2011. http://www.history.navy.mil/special%20Highlights/asian/API-12Apr11.pdf. Retrieved 1 May 2011. "Gordon Chung-Hoon, a Hawaiian-born Chinese American and a 1934 U.S. Naval Academy Asian first the graduate, was the first Asian was graduate, American to command a Navy (DD 502). Sigsbee warship, USS caused attack When a kamikaze attack caused kamikaze a When explosions and flooding on board the destroyer, Chung-Hoon directed damage control, enabling the crew to save the ship. his for Cross Navy Awarded Awarded the Navy Cross for his the actions, he was later promoted to rear admiral, making him the officer flag American first first Asian American flag officer Asian ."

- ^ "Meet the Generals and Admiral". JAVA Advocate (Japanese American Veterans Association) XVIII (2): 9. 2010. http://www.javadc.org/images/JAVA%20Advocate%20Jun-Dec%202010.pdf. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Julianna Goldman (6 December 2008). "Obama to Name Eric Shinseki to Head Veteran Affairs (Update1)". Bloomberg. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=aAJN0eI6vj9Y. Retrieved 2 May 2011. "Shinseki, who served in the Army for 38 years, became the highest-ranking Asian-American in U.S. military history when he was named chief of staff in 1999."

- ^ "Racial Composition of New Enlisted Recruits in 2006 and 2007". The Heritage Foundation. 2008. http://www.heritage.org/static/reportimages/3E59D41279449CAB99F8C7CF54E02351.gif. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ Public Affairs Office (21 June 2010). "News Release". United States Military Academy. http://www.westpoint.edu/Dcomm/PressReleasesbd/nr41-10class_of_2014_RDay.html. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ "2014 Class Portrait". United States Naval Academy. http://www.usna.edu/admissions/USNA%202014%20Class%20Portrait.pdf. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ Tammie Adams (2 July 2010). "Focus on newcomers: Class of 2014". Colorado Springs Military Newspaper Group. http://csmng.com/2010/07/02/focus-on-newcomers-class-of-2014/. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

Asian Americans East Asian

South Asian2 Southeast Asian Burmese · Cambodian · Filipino · Hmong · Indonesian · Laotian · Laotian Chinese · Mien · Singaporean · Thai · VietnameseOther History 1 The US Census Bureau reclassifies anyone identifying as "Tibetan American" as "Chinese American". [1].

2 The US Census Bureau considers Afghanistan a South Asian country, but does not classify Afghan Americans as Asian. [2]United States in World War II Home Front American music during World War II • United States aircraft production during World War II • Greatest Generation

American WomenWomen Airforce Service Pilots • Women's Army Corps• Woman's Land Army of America • Rosie the RiveterMilitary participation Army (Uniforms) • Army Air Force • Marine Corps • Navy • Service medals (Medal of Honor recipients)

EventsList of Battles • Attack on Pearl Harbor • Normandy landings • Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and NagasakiMinoritiesDiplomatic participation External links

Categories:- Military history of the United States

- History of racial segregation in the United States

- American people of Asian descent

- Asian-American history

- American military personnel of Asian descent

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.